Ed’s Note: Welcome to the Twin Peaks rewatch series. To celebrate the return of Twin Peaks on May 21, we’re going to go through every episode at the speed of the show. One episode per day, including Saturday and Sunday, should culminate sometime close to the premiere. For the purposes of this series, as per the earlier essay The Four Placements…, I’m moving Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me into the middle of the series.

For the purposes of this rewatch, we’re also going to take it as a note that everybody has seen the series and massive spoilers will occur during this series as we tie the strings together. As such, the spoiler-filled “The Four Placements” could be read before this.

In the Beginning…

There’s a big reason that many critics give generous ratings to pilot episodes: pilots have the singular duty to build the foundation that the rest of the series will build upon. Pilots have to introduce the main characters, their relation to one another, the setting of the world, and the rules upon which the series will operate. If a pilot manages to achieve most of these goals, it deserves a passing grade. Pilots that manage to accomplish all of this while setting a proper tone for the series are inducted into the television annals of history.

David Lynch’s handling of the Twin Peaks pilot is a masterful introduction of a complex world while balancing the precise tone that waffles between quirky humor and genuine pathos, always threatening to dive deep into the ethereal otherworldliness that eventually dominates the series. Over the course of the 94-minute pilot, Lynch introduces no fewer than 35 characters and 10 plot lines that will all morph and circle each other in a whirlpool of soapy small town intimacy. Almost every beat of this pilot is essential and important, every scene delivering essential information that sets up a variety of mousetraps to ensnare Twin Peaks’ residents. Though the series is famous for its frequent dives into the spiritual and supernatural, the pilot stays grounded in the small town reality of Twin Peaks, WA.

As the haunting tones of Angelo Badalamenti’s iconic theme song swell to open the show, Twin Peaks opens with a shot of a Wren in an evergreen tree, creating a mythic connection with his previous film Blue Velvet. Both stories are cut from the same cloth, exploring the underground nature of corruption in small town America masked by 1950s idealism. Blue Velvet‘s Lumberton, NC is a logging exurb where sleepy suburban neighborhoods border industrial parks just by crossing the railroad. Lumberton is the type of town where a young man can live in an idyllic bubble so fragile that a single walk through a vacant lot can drag him into a world of drugs and sexual deviance. When young Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLahlan) discovers a severed ear, his curiosity leads him to the underground society of Frank Booth that seethes beneath Lumberton’s whitebread surface. In the middle of Blue Velvet, as Jeffrey is entwined in the dealings of a masochistic lounge singer and an abusive addict, Sandy (Laura Dern), Jeffrey’s girlfriend, remembers a dream about existing in a dark world where all the robins had flown away. These robins represented love, and their return would signal that the world had been restored to its happier existence. At the end of Sandy and Jeffrey’s adventures into the wrong side of town, robins return to their small town.

As the haunting tones of Angelo Badalamenti’s iconic theme song swell to open the show, Twin Peaks opens with a shot of a Wren in an evergreen tree, creating a mythic connection with his previous film Blue Velvet. Both stories are cut from the same cloth, exploring the underground nature of corruption in small town America masked by 1950s idealism. Blue Velvet‘s Lumberton, NC is a logging exurb where sleepy suburban neighborhoods border industrial parks just by crossing the railroad. Lumberton is the type of town where a young man can live in an idyllic bubble so fragile that a single walk through a vacant lot can drag him into a world of drugs and sexual deviance. When young Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLahlan) discovers a severed ear, his curiosity leads him to the underground society of Frank Booth that seethes beneath Lumberton’s whitebread surface. In the middle of Blue Velvet, as Jeffrey is entwined in the dealings of a masochistic lounge singer and an abusive addict, Sandy (Laura Dern), Jeffrey’s girlfriend, remembers a dream about existing in a dark world where all the robins had flown away. These robins represented love, and their return would signal that the world had been restored to its happier existence. At the end of Sandy and Jeffrey’s adventures into the wrong side of town, robins return to their small town.

In mythology, Robins and Wrens are yin and yang birds. Robins arrive in the summer and rule over warmth and happiness. The Wren will arrive in the winter and rules over darker periods of coldness, hardship and strife. Just as Blue Velvet concluded its adventure with Robins in the summer, Twin Peaks opens with a wren in the winter. The normal title shot of Twin Peaks happens over a grey rainy day in the pacific northwest (there’s no shortage of those for 9 months of the year here) where the deciduous trees have already shed their leaves though the evergreens maintain their foliage. Winter had arrived in the small sleepy town of Twin Peaks, WA. But, the snow is already melting away, and after the winter comes the spring.

Fun fact: David Lynch originally wanted the population of Twin Peaks to be 5,201. But, fearing urban alienation, the network demanded the population be more “suburban” and Lynch raised the population to 51,201.

The title sequence closes at the bottom of Snoqualmie falls at the foot of the Great Northern Hotel. The ripples in the water give way to images of ducks swimming in a stream. Then, a multi-level lakeside lodge with birds playing on the shore. Finally, a black porcelain statue of two dogs as Josie Packard (Joan Chen) puts on eye makeup, holding her brush as if to slit her eyes open while she hums so softly its barely heard over the swell of Laura Palmer’s theme.

At the risk of sounding obvious, Josie Packard is the first human character Lynch introduces us to, an odd choice given how ancillary her character is to Laura Palmer’s actual story. Josie owns the Packard Sawmill after her husband, Andrew Packard died under strange circumstances two years prior. She lives with Andrew’s sister, Catherine Martell (Piper Laurie) the sawmill’s functional operations and financial executive. Where Catherine manages the business and planning side of the compay, her husband, Pete, manages the personnel. It’s Pete who gets the actual first line of the show, “Goin’ fishin’.” In the next scene, a mere four minutes into the episode (including the 2:40 title sequence), Pete discovers a body, dead and wrapped in plastic.

At the risk of sounding obvious, Josie Packard is the first human character Lynch introduces us to, an odd choice given how ancillary her character is to Laura Palmer’s actual story. Josie owns the Packard Sawmill after her husband, Andrew Packard died under strange circumstances two years prior. She lives with Andrew’s sister, Catherine Martell (Piper Laurie) the sawmill’s functional operations and financial executive. Where Catherine manages the business and planning side of the compay, her husband, Pete, manages the personnel. It’s Pete who gets the actual first line of the show, “Goin’ fishin’.” In the next scene, a mere four minutes into the episode (including the 2:40 title sequence), Pete discovers a body, dead and wrapped in plastic.

The Palmers

The dead body is that of Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee), Twin Peaks’ teenage sweetheart and Homecoming Queen. She’s an All American Student who volunteered at Meals on Wheels, dated captain of the football team Bobby Briggs (Dana Ashbrook), and was best friends with bookish Donna Hayward (Lara Flynn Boyle). She’s the type of girl whose good nature is known to the whole community, and her murder (as well as the discovery of the deeply violated Ronnette Pulaski, daughter of a mill worker) was felt so deeply that Josie felt compelled to shut down the mill for the day. But, Laura lived a double li

The dead body is that of Laura Palmer (Sheryl Lee), Twin Peaks’ teenage sweetheart and Homecoming Queen. She’s an All American Student who volunteered at Meals on Wheels, dated captain of the football team Bobby Briggs (Dana Ashbrook), and was best friends with bookish Donna Hayward (Lara Flynn Boyle). She’s the type of girl whose good nature is known to the whole community, and her murder (as well as the discovery of the deeply violated Ronnette Pulaski, daughter of a mill worker) was felt so deeply that Josie felt compelled to shut down the mill for the day. But, Laura lived a double li

fe, one that touched a number of community members who ignored her cries for help while they took advantage of her dysfunctional emotional state.

On the surface, Laura Palmer is the type of idealized teenager whose absence in the morning is immediately distressing. That morning, her mother Sarah (Grace Zabrieski) is gathering her wits after being unwittingly drugged the night before (Fire Walk With Me). She’s fully dressed, aggravated, stressed out, and already smoking a cigarette while calling for Laura to come down for breakfast. But, Sarah feels…no, she knows something wrong is happening in the house, and maybe even to her family. One of the deeply distressing aspects of rewatching Twin Peaks is seeing how each and every character who knew Laura ignored the signs that she was in trouble, and Sarah Palmer is the most tragic and unnerving example of that ignorance.

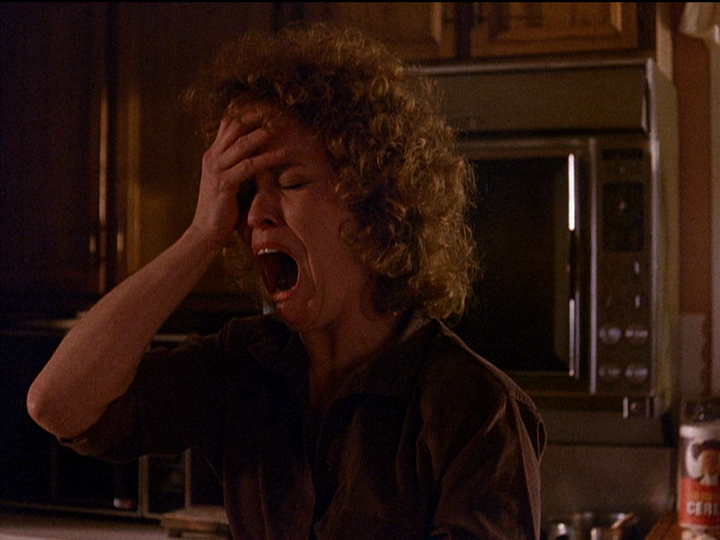

Sarah’s first lines are calling for her daughter to come down for breakfast. “Laura. Sweetheart. I’m not going to call you again,” rings out into dead air. She quickly admits to herself, tiredly, meekly, “yes, I am.” Of all the fantastic performances in this show, Grace Zabriskie’s portrayal of Sarah is the most nuanced and heartbreaking of the show. In 8 minutes, she steadily breaks down from an exhausted doting mother who makes breakfast for her family to having her whole world shatter as she comes to terms with the evil she’d been ignoring for years (even as it slept in her bed).

Sarah’s first lines are calling for her daughter to come down for breakfast. “Laura. Sweetheart. I’m not going to call you again,” rings out into dead air. She quickly admits to herself, tiredly, meekly, “yes, I am.” Of all the fantastic performances in this show, Grace Zabriskie’s portrayal of Sarah is the most nuanced and heartbreaking of the show. In 8 minutes, she steadily breaks down from an exhausted doting mother who makes breakfast for her family to having her whole world shatter as she comes to terms with the evil she’d been ignoring for years (even as it slept in her bed).

In the prequel film Fire Walk With Me, Sarah clearly knows something unsavory has been going on between her husband Leland and Sarah. In that film, she’s a chain smoking stressed out maniac of a mother, unable to control the passive abuse happening in front of her face, nevertheless the grotesque abuse happening behind her back. When Laura comes home for dinner one night, Sarah stresses out while Leland pervertedly harasses Laura about washing her hands and being clean for him, before leering at her about the boys she’s been with based on her split heart necklace. Even as she’s trying to protect her daughter from Leland’s emotional, Sarah is trying to keep the family together; if everybody acts happy then nothing is wrong, right? Sarah blinds herself to the full extent of Leland’s abuse and the damage he inflicts on Laura. It’s only because of Laura’s death that, during the course of Twin Peaks, Sarah has to come to terms with what she’s been excusing in her own home. Regardless of how much or how little culpability Sarah may have in the situation, her primal screams of despair upon learning of Laura’s death is still one of the many truly soul-scarring moments in the show.

In the prequel film Fire Walk With Me, Sarah clearly knows something unsavory has been going on between her husband Leland and Sarah. In that film, she’s a chain smoking stressed out maniac of a mother, unable to control the passive abuse happening in front of her face, nevertheless the grotesque abuse happening behind her back. When Laura comes home for dinner one night, Sarah stresses out while Leland pervertedly harasses Laura about washing her hands and being clean for him, before leering at her about the boys she’s been with based on her split heart necklace. Even as she’s trying to protect her daughter from Leland’s emotional, Sarah is trying to keep the family together; if everybody acts happy then nothing is wrong, right? Sarah blinds herself to the full extent of Leland’s abuse and the damage he inflicts on Laura. It’s only because of Laura’s death that, during the course of Twin Peaks, Sarah has to come to terms with what she’s been excusing in her own home. Regardless of how much or how little culpability Sarah may have in the situation, her primal screams of despair upon learning of Laura’s death is still one of the many truly soul-scarring moments in the show.

And then there’s Leland Palmer (Ray Wise). Despite having a late night, he’s up bright and early to have a meeting with Ben Horne, owner of Twin Peaks’ hotel The Great Northern, and a group of Norwegian investors to develop a country club under the title “The Ghostwood Development Project.” Though he’s still riding high on the adrenaline of violating Ronette Pulaski and murdering his own daughter, the audience doesn’t know this. The first time through the pilot, his performance is pitched perfectly to sell the red herring, but it is also one of the few false notes upon the rewatch. Throughout the series, when Leland is possessed by the spirit of his evil, he takes on a different persona: one that’s just a couple degrees off center, one that’s just a bit too happy, too joyous, and perhaps too forced. It is a mask, after all. But, in the pilot, though Leland is probably still being acted upon by his other persona, he’s acting like Non-Evil Leland.

The first 15 minutes of Twin Peaks is a masterpiece unto itself. Not only does it introduce the audience to the world bit by bit, it also sets up the main plot (who killed Laura Palmer?) and it introduces and emotionally destroys two primary characters (Leland and Sarah). The pilot also manages to set up the Ghostwood Development Project subplot that will consume many of the B-characters. But, Lynch isn’t even close to done; he still has 8 more subplots and romantic triangles to set up and 20 more characters to introduce.

These first 15 minutes do an immense amount of heavy lifting. Twin Peaks isn’t just a mystery about Who Killed Laura Palmer. It’s about the tragedy of a family after their offspring has been lost forever. It’s about the tragedy of a town where the absence on one person ripples through seemingly every family and individual. It’s about discovering the monsters who live among the sheep. But, most importantly, Twin Peaks is about how a town with secret lives can function as an system that enables and encourages abuse by hiding emotional and physical damage under the rug of normalcy. These fifteen minutes show how the stone of Laura’s death creates immediate ripples and cracks. Deputy Andy sobs as he tries to take photos. The town doctor is also the doctor that delivered her. The sheriff knows who she is without having to think about it. Laura’s death is already rippling through the various rings on a deeply personal level.

Without having gone through the series of Twin Peaks or of having watched Fire Walk With Me, the real theme of Laura as an abused girl is notably absent. At the start of the project, David Lynch famously didn’t want to reveal who killed Laura Palmer. He thought the mystery was best left unsolved. He was wrong. But, the various red herrings he left pulled themselves together to form a potent story by the end. If you watch Fire Walk With Me immediately before the pilot of Twin Peaks, the tone irrevocably shifts into something ghastly and cruel.

As the investigation into Laura’s life kicks into high gear, the police uncover Laura’s troubled double life that includes discovering the baggie of cocaine in her diary, and the thousands of dollars in her safe deposit box along with the sexy personals magazine Fleshworld. It’s only over the course of the next 15+ episodes that the full picture unfolds that we’ve been dissecting the life of a girl who had been sexually abused by her father for years, was connected to everybody, and yet nobody ever did anything to help her. Her boyfriend wanted somebody to acknowledge his contributions, and dealt drugs for sex and companionship. Her counselor treated Laura as a perverted show for his own fantasies. Her best friend used her as a way to feel edgy and popular. The list goes on. It’s horrific, it’s tragic, and, as Twin Peaks suggests, it’s terrifyingly common. That’s the real power of Fire Walk With Me. It removes the mystery of Twin Peaks and gets right at the soul of the show, the main story is about the tragedy of Laura Palmer and how nobody could protect her. The whole show is about the cycles of abuse and the lengths we go to not talk about it.

In light of that, Twin Peaks is also about how life must move forward despite the black tragedy of Laura Palmer:

- Laura’s boyfriend, Bobby, is now free to pursue his affair with Shelley Johnson, the married young waitress of the Double R.

- Shelley Johnson is physically and emotionally abused by her cheating, drug-dealing husband Leo, but hides it in the pursuit of normalcy.

- Leo is a violent sociopath trucker who also dealt drugs to Bobby for Laura.

- Laura’s secret boyfriend James Hurley can now pursue a romantic affair with Laura’s best friend, Donna Hayward.

- Donna, in turn, will eventually find the strength to leave her semi-abusive relationship with Bobby’s best friend, Mike Nelson.

- James’ uncle, Big Ed Hurley, is cheating on his slightly abusive drape-obsessed wife Nadine with Norma Jennings, owner of the Double R.

- Later, we find out that Norma has her own history with a violent man.

- Police Officer Andy Brennan is having a love affair with the police receptionist, Lucy.

- Sheriff Truman and Josie Packard are having a DL romantic engagement.

- Catherine is cheating on her husband with Ben Horne who, in turn, is cheating on his wife.

All of this noise, all of these entaglements, all of this LIFE was happening while Laura Palmer was being abused, and will continue happening after she died. Laura Palmer is murdered, life goes on.

Dale Cooper and The Investigation

If Laura provides the purpose of Twin Peaks, FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) is the anchor and the audience surrogate. All activity seems to swirl around him, but he doesn’t appear for over half an hour. Dale is the town outsider newly arriving to Twin Peaks, WA just to investigate Laura’s murder because it seems related to the murder of Teresa Banks, a girl in backwater Oregon (featured in Fire Walk With Me). In classic noir terms, he’s The Continental Op – an outsider who comes into town to clean up the corruption. He’s Bill Munny in Unforgiven, and The Dressmaker in The Dressmaker. Like The Dressmaker, he is two heads intertwined – the real and the spiritual, the work and the social, the yin and the yang.

If Laura provides the purpose of Twin Peaks, FBI Special Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan) is the anchor and the audience surrogate. All activity seems to swirl around him, but he doesn’t appear for over half an hour. Dale is the town outsider newly arriving to Twin Peaks, WA just to investigate Laura’s murder because it seems related to the murder of Teresa Banks, a girl in backwater Oregon (featured in Fire Walk With Me). In classic noir terms, he’s The Continental Op – an outsider who comes into town to clean up the corruption. He’s Bill Munny in Unforgiven, and The Dressmaker in The Dressmaker. Like The Dressmaker, he is two heads intertwined – the real and the spiritual, the work and the social, the yin and the yang.

Dale enters the series recording messages for “Diane” through his tape recorder. Diane, ostensibly Cooper’s secretary, is the great unseen character of the series and may just be a figment of Cooper’s imagination…another side of him, an unseen yang to his yin. His recordings is a fascinating stream of consciousness rant that alternates between the mundane and the factual. Cooper’s notes alternate between notes on the case and prices of his meals interjecting observations about the evergreens and the cherry pie he had at the Lamplighter Inn. His first conversation with Sheriff Truman follows the same pattern:

“Sheriff, let me stop you in the hallway for just a second. There’s a few things that we gotta get straight right off the bat. I learned about this the hard way, and its best to talk about this up front. When the Bureau gets called in, the Bureau’s in charge. Now, you’re gonna be working for me. Sometimes local law enforcement has a problem with that. I hope you understand.”

“Like I said. We’re glad to have you here.”

“Sheriff. What kind of fantastic trees do you have growing around here? Big, majestic…”

“Douglas fir.”

“Douglasss firrr. [slight pause] Can somebody get me a copy of the coroner’s report on the dead girl?”

This alternating rhythm – business and casual conversation, the natural world we overlook and the unnatural world we’re focused on, the real and the supernatural – is the same rhythm the show operates on, and Cooper is the only one who has enough experience to have an attempt to control the alternating forces. Others try to control the forces, but in meager ways. Dr. Jacobi, for instance, wears glasses of red and blue lenses. He has a sense that this dichotomy exists, but has no idea what to do with it. Cooper, the outsider, can see the flow of life, is open to the possibilities, and is willing to ride it out.

Life in Twin Peaks is everything big and small. Coffee and Pie are the two delicious substances that create an intangible connection between everybody in the whole world. Cooper gives himself a little gift every day, including, at one point, a slice of pie. Coffee is rich, dark, and black, providing us with the vitalest of energy we need to continue through even the bleakest of moments. When our world is disrupted, the coffee goes stale (Fire Walk With Me) or somebody puts a fish in the pot. Cooper is obsessed with this connecting tissue.

It’s only with Cooper’s arrival that we start collecting the various clues to unlocking Laura’s life and her death. He finds the Letter R under her ring finger fingernail, right where he expects it. They unlock Laura’s diary, which includes the safety deposit box and cocaine residue (a moment where the Sheriff admonishes Cooper that “He didn’t know Laura Palmer”), a secret date with “J,” a small box of chocolate bunnies, the murder location (an abandoned boxcar), her relationship with James, Laura’s gold necklace with half a gold heart, a bloody note with “Fire Walk With Me” written in blood, Laura’s safety deposit box with $10,000 and a copy of an adult magazine with a photo of Ronette Pulaski on the same page as a photo of Leo Johnson’s truck. These notes don’t add up to much yet, but but there’s a lot of story that leaves all these trace elements lying around.

And then, there’s James, the kicked puppy dog of a secret boyfriend. He gives the final clue of the evening, his version of what happened the night before Laura disappeared. He was with Laura, who was acting even more desperate than normal. She says she saw Bobby kill somebody, and then went out into the woods on her own. But, mostly, he finally figured out that Laura had a lot of secrets, and was living a double life, but the surface finally b r o k e.

James’s story is illustrative of Twin Peaks’ larger problem. Laura is freaking out, ranting, saying that she’s in trouble, not making sense, and is utterly distressed. At a red light in the middle of nowhere, she jumps off James’ bike and runs into the dark. Does he go after her? Does he chase her? No. He rides off on his bike and rides around for hours. He has no alibi for the night because he was too busy ignoring the problematic signs that were right in front of him. In the end…Laura dies. And nobody did anything to help her.

In the end, James is arrested, and thrown in jail along with Mike and Bobby. Even though James and Donna buried his half of the heart necklace with a rock, a mysterious hand steals it, to the chagrin of Sarah. And, Dale Cooper decides to stay at The Great Northern on top of the waterfall…

Subplots

Life must go on after Laura’s death, and Twin Peaks has a whole litany of subplots occuring at any given time. In my notes, I have 13 intertwined subplots being introduced during the course of the pilot, including four separate love triangles, three romantic relationships, the Ghostwood Estates, and the mysterious case of The Hurley’s Drapes.

Life must go on after Laura’s death, and Twin Peaks has a whole litany of subplots occuring at any given time. In my notes, I have 13 intertwined subplots being introduced during the course of the pilot, including four separate love triangles, three romantic relationships, the Ghostwood Estates, and the mysterious case of The Hurley’s Drapes.

Mostly, each episode of Twin Peaks represents a 24 hour period, and each story moves forward in the oh-so-incremental fashions as developed by daily soap operas.

- The Ghostwood Development Plan is almost sold to a bunch of Norwegian investors until Audrey tells them about Laura Palmer’s murder, and they flee the hotel.

- The love knot between Leo/Shelley/Bobby/Laura/James/Donna/Mike is hilariously convoluted. Keeping up with who is kissing on who is a full time job. This gets even more complicated with the Laura/Bobby/Leo drug triangle of cocaine and footballs.

- Nadine/Big Ed/Norma have a great tragic love triangle that makes for an awesomely absurd and upsetting reveal late in Season 2.

- Big Ed and Nadine get their drapes installed, but Nadine hates how they sound. I sympathize.

- The pilot introduces two relationships that get bigger later on. The romance between Josie and Truman becomes a bigger thing, and this is the first hint we get of Catherine and Ben Horne’s extramarital affair.

- Poor Johnny Horne, the mentally challenged son of Ben Horne and sister of Audrey, never gets much of a story arc. But, he exists and he has one big important line coming up.

Stray Notes

- I have an automatic dislike of James that’s totally a residual of his Season 2 post-funeral storyline to nowhere. I hate that plot so much that I am now starting to retroactively hate James before he even gets there. You guys, I’m really dreading those dead episodes later in the series. They’re fucking painful.

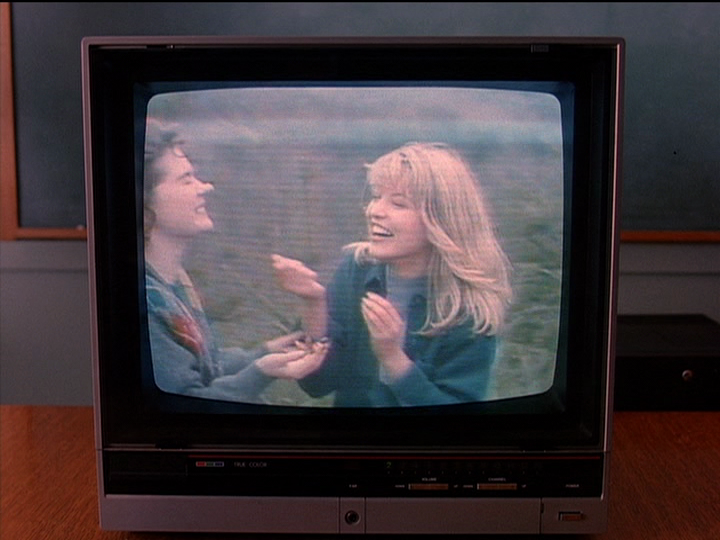

- James’s first persona is perhaps the performance that rings the most false on a rewatch. At high school, before anybody has learned that Laura died, James is genuinely happy and bouncy (one of the only times he doesn’t look like somebody kicked his puppy). His energetic boisterous is completely at odds with what happened the night before, even within the context of the episode. If my girlfriend had turned into a desperate monster of sorts, ranting about a bunch of stuff that made no sense, and then fled into the woods in the middle of the night, I wouldn’t be genuinely cheerful the next morning.

- One aspect of Twin Peaks that I kind of resent is its treatment of Ronette Pulaski. Laura is the daughter of a semi-high-powered attorney – the ideal case for innocence lost. But, Ronette is the daughter of a sawmill worker; she’s somebody who could possibly be from the “wrong side of the tracks,” so to speak. When Ronette engages in the exact same behaviors as Laura Palmer, that type of rebellion is almost to be expected from that type of girl. Though her father and mother seem to be doting parents, something may or may not be going on in their home as well. People are shocked when they discover Laura is secretly a coke-addicted sex fiend who prostitutes herself for money. These symbols of behavior are seen as cries for help. However, when Ronette engages in the exact same behavior, nobody reacts as if she too is crying for help. Nobody wonders what is happening in Ronette’s life that pushes her to engage in the same behaviors. She enters the series as a clue and dies as a clue.

- The exteriors of Twin Peaks were filmed in Snoqualmie, WA, a town about 30 miles east of Seattle in the western foothills of the Cascades. But Dale puts Twin Peaks, WA, as 5 miles south of the Canadian Border and 12 miles west of Idaho in a no-man’s land of snow and brrrrrr. The mountains really do change the weather dramatically. Also, it takes about five hours to go from border to border. This is important when we talk about Deer Meadows, OR.

- The way Mike says “He’s my best friend!” has been forever ruined by Tommy Wiseau’s performance in The Room.

- Audrey’s coffee scene with Judy the Concierge is one of my favorte scenes. It’s also the summary of the series. There’s a bunch of dirty coffee in a cup, cup held back by a wall of styrofoam, an artificial man-made construction. Audrey penetrates the surface, and all of the contained detritus within the cup spills all over the desk, distressing Judy, trashing the existing paperwork, and Audrey sees an excuse to run away.

- Margaret Lanterman, better known as The Log Lady, makes her first appearance at the emergency town meeting by flicking the lights on and off to slience the murmuring crowds. She’s controlling electricity, a sign of the supernatural elements at work in Twin Peaks. The Log Lady is able to see things happening between the worlds, and speaks in otherworldly terms. The other instance of lights flickering in the pilot? The lights are flickering during Cooper’s initial examination of Laura’s corpse.

- Favorite brief character? Harriet, Donna Hayward’s sister, who writes florid teenage poetry. Her flat, ineffectual, non-covering of Donna’s escaping – “I’m going to tell it to you straight” – is pure hilarity.

- The first appearance of JULEE CRUISE!!! OMG!!! She’s the singer at The Roadhouse, and…I love Julee Cruise, and she needs to be included in everything. If you haven’t checked out her other collaboration with Lynch, Industrial Symphony no 1, you really need to see that yesterday.

- This is also the first appearance of Lucy’s massive donut spread. It’s a good thing this is television, because Lucy is working like a dog. She’s there bright and early in the morning, and she’s at the station until 12:28am, when Sheriff Truman tells her to get back to work. WHAT!? That’s a shit shift.