Tune in Next Week is an ongoing feature, examining serials one chapter at a time. You can watch Chapter Twelve here.

At the end of Chapter Eleven, rubble from the collapsing ceiling of the Forum descended on Buck Rogers and Buddy Wade as Captain Laska dropped bombs on the structure from above. Of course, the situation isn’t as dire as it appeared, but Buck is trapped, his foot wedged under a pillar too heavy for him or Buddy to move. With some quick thinking, he uses his disintegrator ray to break the pillar in half and free himself, and the two heroes are able to join the crowd at the front entrance. Watching Laska’s ship land, he cautions, “We can’t attack until we get reorganized.” However, to his dismay he is informed that the Saturnians still intend to treat with Laska in return for the kidnapped Prince Tallen, even after Buck’s rousing speech and Laska’s bombing of the Forum.

Laska and his men remove Tallen from the ship; Laska leaves the Prince guarded and begins walking toward the Forum to finalize Saturn’s surrender. No sooner has he left than Buck and Buddy subdue the guards and free Prince Tallen. Laska and his other soldiers (including Patten) are soon taken into custody, and the Council reaffirms its commitment to its treaty with the Hidden City. Tallen prepares to launch the Saturnian rocket forces to aid the Earthmen, and Buck takes off in the Kane patrol ship to return ahead of them.

After checking in by radio with the Hidden City, Buck and Buddy fly to Kane’s city, landing on Kane’s now-empty airfield and sneaking in (not even bothering to wear the uniforms of Kane’s men as they did before). They head straight to the dynamo room, where the robot battalions continue their labor. Surprising a guard and keeping him quiet, they survey the living robots; Buck recognizes Krenko, the member of Kane’s council who had been sentenced to wear the amnesia helmet after incurring the Leader’s displeasure. Buck has the captive guard request Krenko be sent up from the floor, and after removing Krenko’s helmet Buck tells him the plan. Just as he did on Saturn, he removes the amnesia filament and has Krenko put the helmet back on, this time returning to the floor and surreptitiously removing the helmets from the other robots, Hidden City soldiers and Kane dissidents alike.

The captive guard breaks loose and sounds the alarm, but it’s too late: enough men have been freed from the amnesia helmets that the remaining guards are overwhelmed. In no time, this new force is at Kane’s door. Kane is busy planning the final strike on the Hidden City, but he has been preempted: the Hidden City air patrol is already on its way. Confronted on one side by the aerial attack and on the other by Buck Rogers and the freed robots, Kane is trapped. Krenko helps Buck fit Kane with his own amnesia helmet, and under orders from Buck Kane commands his air force to stand down. The Hidden City has won.

Back at the Hidden City, Buck Rogers is congratulated and given a new assignment by Air Marshal Kragg: whipping the defeated Kane air patrol into a new defense force. “Master Wade” gets a commission as part of Rogers’ staff. And Prince Tallen arrives just in time to congratulate Buck and receive the thanks of the grateful city. But wait–the radio operator relays news that another of Kane’s squadrons is still in the air! Buck is to report to Dr. Huer’s laboratory right away!

Is it a tease for a sequel? Not quite. Wilma Deering, on duty in the laboratory, knows nothing about any such patrol. Buddy appears and confesses that he made up the report because he knew Wilma would want to congratulate Buck in person, wink wink, nudge nudge, if you know what I mean.* After a painfully awkward silence, Buddy says he knows when he’s not wanted and backs away. Buck and Wilma then passionately embrace do nothing as the screen fades to black.

*Later, they bone hold hands.

OVERVIEW

Now that we’ve seen the complete serial and can look back over the whole pattern, some things stand out more clearly. First, like a football game, the action of Buck Rogers can be seen as a series of thrusts and counter-thrusts into the territories of the two opposing forces, with Saturn as a neutral middle ground that changes hands depending on who has possession of Prince Tallen (who by the terms of this metaphor obviously represents the ball). It’s primarily Buck Rogers and his Hidden City allies who invade Killer Kane’s city, owing to the Hidden City’s superior defense (and being, well, hidden), but Kane does the same through his Lieutenant, Carson, who is able to infiltrate the Hidden City and blow the whole game wide open.

This back-and-forth has the obvious benefit of allowing the reuse of sets (I don’t think there’s any location in this serial that appears only once) as well as easy division into chapters, each incursion being an episode unto itself and a new wrinkle on the larger unfolding plot. It also keeps the aerial dogfighting and space flight (the supposed draw of this character) at a distance; those elements are definitely present, but special effects didn’t really allow them to be front and center all the time, so much of the decisive action is actually Earth- (or Saturn-) bound. (Note that after all that trouble, the involvement of the Saturnian ships is only covered in dialogue; their contribution to the fight isn’t shown at all.)

Second, this serial is typical (even emblematic) of the gee-whiz futurism of the prewar era in that not only is there no problem that cannot be solved by the application of Science! (exclamation point absolutely included), but there are very few if any moral qualms about the use or abuse of the marvelous inventions created thereby. One could argue that Killer Kane’s “outlaw empire” represents the exploitation of scientific achievement without conscience, and it wouldn’t be wrong, but it’s worth noting that even the horrifying amnesia helmet is implicitly acceptable when used to suppress genuine criminality instead of mere dissent.

(A frequent theme of prewar espionage and science fiction was the importance of keeping advanced technology and weapons out of the “wrong hands.” The idea that there might not be anyone righteous or responsible enough to wield such power was a minority view until the reality of the atomic bomb created a shift in perspective that rippled through science fiction and the culture at large.)

Also in line with the “Audie Murphy in space” approach, the heroes of Buck Rogers rarely have to deal with spent ammunition, power outages, or inventions that don’t work, except when narratively convenient. A damaged rocket tube or blown circuit on the dissolvo ray create problems, to be sure, but this is much closer to the sleek, perfected future of Star Trek than the kludged-together junk-heap aesthetic of Star Wars. For the most part, everything works as intended.

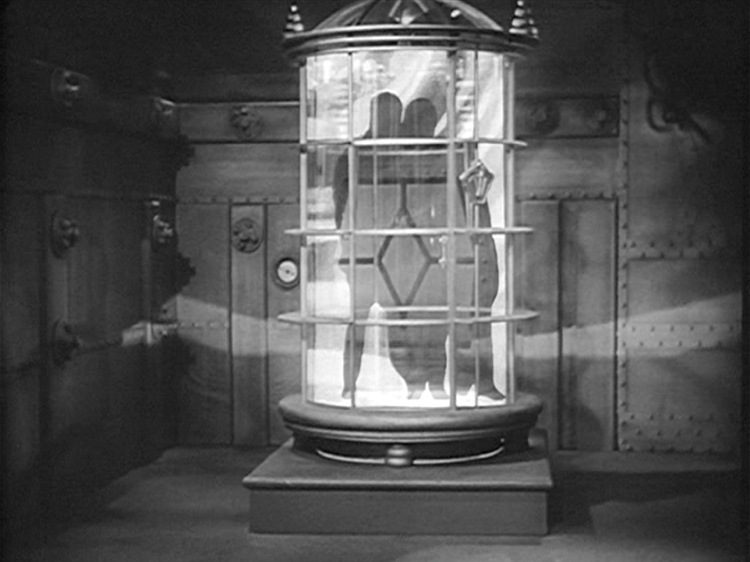

Speaking of Star Trek, and more to the point, the fundamental optimism of Buck Rogers‘ treatment of technology is illustrated by the transporter frequently shown whisking our heroes between Kragg’s headquarters and Dr. Huer’s laboratory. This device isn’t really important to the plot–it’s just one of the many bits of business that quietly reminds us, “Hey, this is the future!”–and in fact it’s never used for any other route, its function apparently dependent on the fixed locations of the terminal chambers. But every time two or more characters got into the transporter together, my mind automatically conjured up something like this . . .

. . . or this . . .

. . . or this . . .

. . . appearing on the other end. Of course, that never happened: this isn’t that kind of story. George Langelaan’s short story “The Fly” wouldn’t be published until 1957 and adapted into the first of several feature films the following year. Science fiction writers had toyed with the unintended consequences of progress before World War II (H. G. Wells could have written a story like “The Fly” if he had thought of it), but that was never a major theme of space opera, which emphasized action, adventure, and invention.

We’ve had some discussions in the comments about whether Buck Rogers could be revived today in a non-ironic way; beyond the clean-cut heroism of Buck Rogers in his 1939 iteration, it’s that faith in technological progress that seems the hardest to retrieve. Star Trek began by putting a thoughtful, progressive spin on that optimistic ethos, but after Star Wars in 1977, even Gene Roddenberry felt compelled to include the possibility of transporter malfunctions in The Motion Picture, and The Wrath of Khan famously explored the fallout of one of Kirk’s well-intentioned decisions from the original series.

AWARDS AND MISCELLANEA

All awards are granted on the basis of in-depth research and rigorous scientific evaluation. Feel free to make the case for your own dissenting opinion in the comments, but know that only my decisions are legally binding. I’ve already sent the awards back in time to 1939; the recipients loved them.

Best Chapter Title: “Revolt of the Zuggs,” Chapter Eight. “______ of the ______” is just good titling, I don’t care what genre we’re talking about.

Best Cliffhanger: There are several good cliffhangers in this serial, many of them classic perils that were seen in many serials (cave-ins, crashes, and falls from great heights were common, as were seemingly fatal gunshots); I think my favorite is the most direct, from Chapter Six, “The Unknown Command,” in which Buck, Wilma, and Prince Tallen are trapped on an out-of-control bullet car that speeds straight into a closed gate, resulting in a fiery (yet still somehow non-fatal) explosion.

Annie Wilkes Award for Most Blatant Cheat: This one has to go to the resolution of Buddy’s fate in Killer Kane’s conference room in Chapter Ten, “Breaking Barriers.” No question.

Coolest Invention: There are many wondrous devices in Buck Rogers, from the airship that was the future of travel in 1939 to the rocket-powered space ships that travel between Earth and Saturn in the twenty-fifth century. There’s the monorail “bullet car” in the Saturnian Forum, and the “degravity belts” and disintegrator pistols that are essential parts of this style of science fiction, not to mention the mind-controlling amnesia helmets. I think my favorite, however, is the “dissolvo ray,” not least for the fact that this is the one invention in the entire serial that provokes some reflection on its strangeness. When commentators use the phrase “sense of wonder” when talking about the Golden Age of science fiction, that’s what they’re talking about.

Least Effective Characters: Guard duty is a shit gig in the twenty-fifth century: even your own allies will sneak by you, trick you, or just push you out of the way to get by you. At least in combat there’s a chance of promotion.

Silliest Costume: The costumes in Buck Rogers are not as silly as they could be, although the aviator caps the heroes wear have never really come back into vogue in subsequent sci-fi. As Hypercube Villain The Ploughman pointed out several weeks ago, the horizontal bands on the black uniforms of Kane’s men sort of resemble a cummerbund, giving them an oddly formal appearance. I think my pick is the Zuggs, however, not so much because of their rubbery face masks but because the Zugg uniform of loose-fitting bicolored tunic looks like something straight out of a music video from the ’80s. Is color blocking in again? I can’t keep up, but suffice it to say that what works on the catwalk doesn’t always come off when you’re a rubber-faced troglodyte from Saturn. The truth hurts, baby.

Favorite one-scene performance: Can there be any doubt that the former robot whom the Zuggs take as a god in Chapter Eight steals his one scene? And we never even knew his name. . . .

What about that guy? I didn’t notice this fellow on the right until I was taking screen shots of Chapter Eleven, but he looks kind of pissed, doesn’t he? I wonder if he was next in line to command the Hidden City forces until Buck Rogers showed up?

And here, from Chapter Twelve, is proof that there are other women on Earth in the twenty-fifth century besides Wilma Deering. If this movie were made today, there would be a trilogy of Expanded Universe novels explaining who she is and her role in the events of the film, and at the very least she’d have a Comic-Con exclusive action figure.

You know, I think that is supposed to be Earth and its moon hanging in the sky over Saturn. It’s not hard science fiction, of course, but the space travel in this serial would make a lot more sense if Prince Tallen lived on Mars instead of Saturn.

The heroes of Buck Rogers as a Dungeons & Dragons party:

Buck Rogers is the Fighter, of course, always first into the fray and ready to defeat evildoers and defend the helpless. He’s not just a mindless mass of muscle, however–his INT is high enough that he knows when to rely on stealth and deception for tactical gain.

Buddy Wade, on the other hand, is all about stealth and deception, making him the perfect Thief.

Although Dr. Huer doesn’t take the field with the others, he is clearly the Wizard of the party, crafting the magic items that give Buck, Buddy, and Wilma the edge in their battles against the forces of evil.

That leaves Wilma Deering to be the Cleric, capable of participating in combat, but also assisting Dr. Huer in making potions and possessed of the nurturing qualities that make her an effective healer. And I’m pretty sure I didn’t see her use an edged weapon even once.

Other characters’ classes include Prince Tallen as the Monk (I know what you’re thinking, but that’s not the only reason: he’s sure as hell not a Bard, and can you think of a single thing Tallen did in this serial? Monk!) and Kragg as a Fighter with enough levels to command others. Killer Kane could be something similar, but I get a real dark Wizard vibe from him, making him the counterpart to Dr. Huer and explaining his access to Helms of Domination (q.v.).

EPILOGUE

The plan was to produce two Buck Rogers serials, just as there had previously been two Flash Gordon serials. However, Buck Rogers didn’t perform as well as hoped at the box office, so instead a third Flash Gordon serial was begun with Buster Crabbe again in the lead. (C. Montague Shaw, who played Dr. Huer, joined Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe as the king of the rock people, his patrician voice issuing from behind a rubber mask.) (Beg pardon, I’m thinking of Shaw’s turn in 1938’s Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars.) Many sets and props, including the bullet car, were reused.

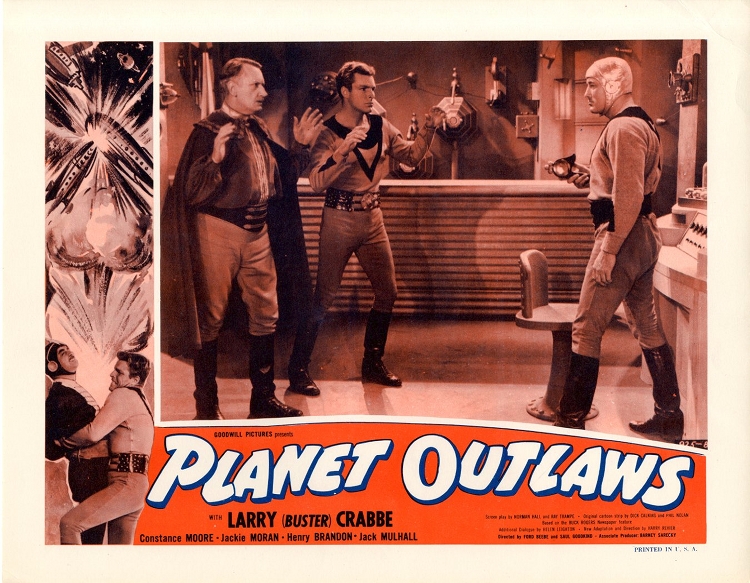

Meanwhile, the Buck Rogers comic strip and radio program continued. In 1950, a short-lived Buck Rogers television series was aired, but no footage survives. In 1953, the serial was rereleased, cut down to feature length (a common practice) as Planet Outlaws (interestingly, a frame story was added that tied the events of the serial to the then-current flying saucer craze; in addition, an explicit parallel was drawn between Killer Kane and the enemies of democracy in the Cold War).

In 1979, following the success of Star Wars and a resurgent interest in space opera, producer Glen A. Larson revived Buck Rogers as a television series (the first two episodes of which were edited into a theatrically-released feature film). Starring Gil Gerard in the title role, the TV series updated the material in ways large and small. With a portentous voice-over and dramatic music, the opening titles lay out Rogers’ new backstory as an astronaut thrown off course and preserved in a state of suspended animation. When I was a kid this was just the right level of bombast to suck me in, and I still feel it’s one of the most effective opening sequences of its time; the fact that the episodes didn’t always live up to the expectations it set was secondary.

Most visibly, Buck Rogers in the 25th Century was titillating in a way that earlier versions hadn’t been; partly this was to fit into the television landscape, competing with hits like Charlie’s Angels. It was also emphasizing a strain that had always been present in space opera, if not always in Buck Rogers itself (Flash Gordon was sexy from the beginning, and think of all those green-skinned women Captain Kirk was said to have seduced) and provided something that Star Wars didn’t have, a reason for Dad to stay in the den and see what the kids were watching. Wilma Deering, played by Erin Gray, in addition to being made a fiercely capable partner and guide to Buck Rogers, was also rendered sensual and provocative, wearing skin-tight uniforms and revealing evening wear. A new character, Princess Ardala (to whom Kane was now merely a right-hand man), was presented as the “bad girl” in contrast to Wilma: Ardala was often torn between plotting against Earth and her desire to possess Buck Rogers, much like Princess Aura from Flash Gordon.

Beyond the ratings-friendly sex appeal, the 1979 series was updated in other ways: in addition to super criminals, Earth of the twenty-fifth century was menaced by empires and factions from other planets, Cold War-style, as well as environmental destruction and the shadow of devastating atomic wars (the pilot episode finds Buck exploring a ruined twentieth-century city in the wasteland outside New Chicago and encountering bands of marauding mutants, like something out of Planet of the Apes or The Omega Man).

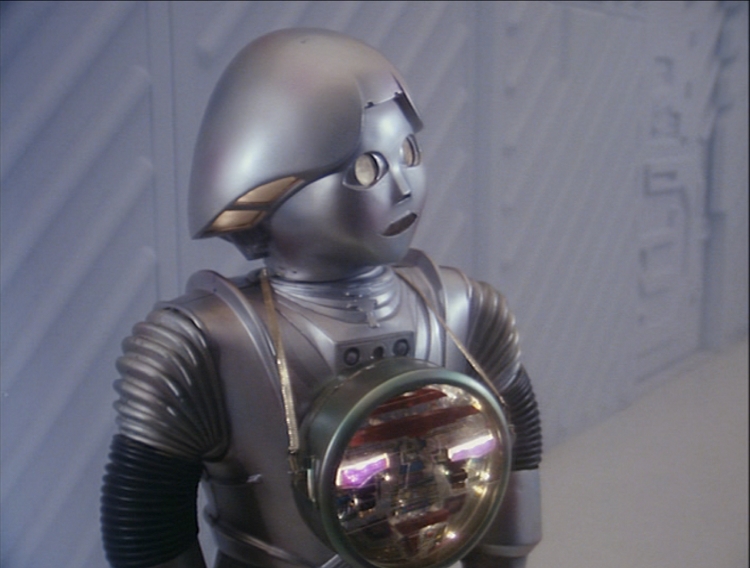

What happened to Buddy Wade?, or The Ghost in the Machine: There is no Buddy Wade in the 1979 series. Instead, comic relief and sidekick duties are performed by Twiki, the lovable robot (voiced by Mel Blanc!) obviously intended as television’s answer to C-3PO and R2-D2. Twiki was the character you followed and laughed along with as a child, and then found grating and superfluous as an adult–sort of like Buddy Wade himself! But you could say that there’s a little bit of Buddy in Twiki, perhaps literally: listen closely when Twiki repeats his catchphrase, “Beedee-beedee-beedee,” and it almost sounds like he’s desperately trying to retrieve a long-buried memory, perhaps of who he used to be: “Buddy . . . Buddy . . . Buddy. . . .”

Buck Rogers in the 25th Century lasted two seasons, and while it has never had the serious reputation of Larson’s other big sci-fi epic, Battlestar Galactica, it is fondly remembered. The 1979 series introduced a classic character to a new generation (one which, I might add, was so hungry for anything like Star Wars that it would have accepted much less, and often did), not to mention providing the basic premise from which Futurama would launch its many parodies of science fiction tropes and properties.

After his serial heyday, Buster Crabbe continued to act in Westerns and B pictures, and starred in a television series, Captain Gallant of the Foreign Legion. In the 1960s and ’70s, as serials and other pop culture of the 1930s became objects of both serious study and nostalgic recollection, Crabbe became a popular fixture on the emerging convention circuit and was a popular guest on college campuses, where his talks were often paired with screenings of his old movies. He appears to have been much like the characters he played: a plainspoken man with little use for the vanities of Hollywood. He died in 1983.

Crabbe lived long enough to appear as a guest star on the 1979 Buck Rogers television series. He played “Brigadier Gordon” (heh heh), a retired officer and flight instructor who returns to duty to aid Earth’s fleet after a plot has grounded most of the active pilots. Speaking over radio headsets during the climactic battle, Buck Rogers (Gerard) compliments Gordon (Crabbe) and asks if they’ve met. Gordon replies, “I don’t think so, Captain. We’re from different times.” After the fighting is over, Rogers asks Gordon where he learned to shoot. Gordon answers, “I’ve been doing that sort of thing since before you were born, Captain.” Rogers replies, “You think so, huh?”, to which Gordon’s wistful response is “Young man, I know so.” I’m a sucker for “passing of the torch” moments, and I’m hard pressed to think of a sweeter example than this one.

We’re fast approaching the ninetieth anniversary of Philip Nowlan’s original novel Armageddon 2419 A.D.; when 2019 arrives, we’ll be as far removed from Gil Gerard’s portrayal of Buck Rogers as Gerard was from Crabbe’s. Will another actor be there to take up the mantle of the twenty-fifth century’s reawakened hero? A new Buck Rogers is listed as being “in development” (as is another attempt to revive Flash Gordon). Of course, it may come to nothing, and recent attempts to bring pulp-era heroes to the big screen have performed poorly. However, given the renewed popularity of Star Wars and Star Trek and the importance of name recognition in the crowded film marketplace, I wouldn’t count Buck Rogers out. It’s likely that a new Buck Rogers would reflect our times and our anxieties, and that’s as it should be: one hopes, though, that it would follow the example of past iterations by representing the best values of our present and bravely facing the future, whatever it might bring.

This brings Tune in Next Week to a close for now. Thanks to all who’ve followed along and shared their comments. If you’ve watched all twelve chapters of Buck Rogers, what did you think? If this was your first serial, did it live up to your expectations? For my part, this was the first time I’ve stretched out a serial, watching only one chapter a week. It wasn’t a totally authentic recreation of original conditions–I didn’t always watch a chapter on the same day of the week, and I had the luxury of watching more than once and revisiting past chapters to confirm details–but I do think that by spreading it out over time I got to know the characters and settings in a way comparable to following a season of TV in real time (an experience that itself may soon go the way of the motion picture serial?). By contrast, when I watched a whole serial and wrote about it within a week it would often be quickly forgotten afterward. Finally, is there interest in continuing this? Let me know your suggestions, and thanks again for reading!