Tune in Next Week is an ongoing feature examining serials, one chapter at a time.

As our story begins in 1938, Lieutenant Buck Rogers (Buster Crabbe) is piloting an experimental dirigible over the North Pole with the youthful Buddy Wade (Jackie Moran; Buddy’s official capacity is not revealed, but it seems fair to describe him as an Ensign, maybe) and two officers. Due to a heavy blizzard, radio contact with their observatory base is intermittent at best. The perspective switches between the dirigible and the helpless ground control crew, which includes the inventor Dr. Morgan and Buddy’s father. Rogers is doing his best to keep the ship above the blizzard, but the officers panic and, seizing the controls, send it into a dive. When Rogers takes control and struggles to right the airship, the officers both bail out into the storm, almost certainly to death by freezing.

Over the radio, in a last-ditch effort to save the remaining crew, Dr. Morgan instructs Buddy to open the valve on a tank of experimental “Nirvano gas” in the cabin. As Morgan explains to his colleagues, the gas should induce a state of suspended animation, preserving Buck and Buddy in safety until the storm passes and a rescue mission can locate them. The dirigible crashes before Buck can send coordinates of their location, and triggers an avalanche that completely covers the ship in ice, ensuring that Morgan and his crew will never find them.

Then follows a nifty montage, complete with giant scrolling numbers illustrating the passage of years: 1940 . . . 2040 . . . 2140, and so on, ending in 2440, when a futuristic flying machine lands near the glacier that entombs the crashed airship. Two soldiers observe the entrance to the ship’s cabin, revealed by a thaw, and upon investigating release the gas that has kept the two pilots asleep. Unsurprisingly, when Buck and Buddy wake up they are confused by the soldiers’ unfamiliar uniforms, and they are later shocked to learn that they have been in hibernation for five centuries. Taken as prisoners, they are brought to “Scientist General” Dr. Huer (C. Montague Shaw), who confirms their identity and explains to them the ongoing war between Killer Kane and the Earth forces. Yes, man now travels through space, and is even in communication with other planets.

It’s a lot to absorb, but little time is spent on future shock or mourning those left behind. There’s work to be done and adventure to be had! Rogers wastes no time in offering suggestions on breaking Kane’s blockade of Earth by sending a remote ship as a decoy, giving a daring pilot a chance to slip through and beg for help from allies on Saturn. Despite the protests of Huer’s other advisors, Huer authorizes the plan, and Rogers himself is given the opportunity to pilot the ship, along with Buddy and Lieutenant Wilma Deering (Constance Moore). The plan almost works, with Kane’s forces destroying the decoy ship, but Rogers’ ship is spotted and fired on just as it reaches the ringed planet: coming into Saturn’s atmosphere too fast, it burst into flame and plummets toward certain doom. The end.

Or, it would be the end, if this weren’t only the first of twelve chapters. We can be confident that Rogers and company will get out of this one, but we won’t know how until we get to the next chapter. As the first installment, “Tomorrow’s World” carries the burden of establishing the setting, the characters, and the main conflict, with the additional burden of giving half its running time to a twentieth-century origin story. So it’s not too surprising that much of this chapter feels perfunctory: serials are generally plot-driven affairs, and whatever characterization or thematic development we get is gravy.

Two points are noteworthy: as I mentioned last week, Buck Rogers is first and foremost a fantasy of dropping into an unfamiliar situation and providing the leadership, competence, and just plain guts that are needed at that moment. So it’s a foregone conclusion that Rogers will end up flying one of Earth’s ships, leading the mission. It’s his name in the title, after all. In most versions of this story, however, the hero has to prove himself: John Carter, who established the template for this type of character, spent chapters, whole books even, as a slave, a prisoner, and a warrior before becoming the “Warlord of Mars.” In another serial, Undersea Kingdom, Crash Corrigan saved the life of Sharad, high priest of Atlantis, and demonstrated his strength and honor in other ways, before being made the head of the Atlantean army. But we don’t really have time for that. Realism isn’t the goal of this kind of entertainment, but if it helps suspend your disbelief you can imagine a period of offscreen acclimation and recognition of Rogers’ skills. (That’s the approach taken in the 1979 Buck Rogers TV series, which had the luxury of stretching things out and giving the characters more room to breathe.)

Second, the name Wilma Deering would have been instantly known to fans of Buck Rogers’ comic strip and radio adventures: she’s Rogers’ partner in adventure and love, and her presence in the control room and on the ship with Buck and Buddy is a clear sign of her importance to the story. The pairing of the hero with a female love interest, however thinly sketched, is a common feature in genre fiction, so a viewer could expect them to get together even without familiarity of the specifics. So far, she’s the only woman in the story (sadly, not an unusual situation for serials). But as yet, Deering doesn’t have much to do: only a few lines of dialogue, and not much explanation as to why she’s sent on the mission. I can only hope that her role gets developed as the series goes on.

The changes made from the source material are actually not too egregious: the biggest is the presence of a sidekick with Buck Rogers at the beginning. In every other iteration of Buck Rogers that I’m aware of, Rogers is thrust into the future alone. In the comics and radio show, Buddy is Wilma Deering’s younger brother, a citizen of the twenty-fifth century himself. Compared to some of the radical changes to source material seen in other serials, it’s a minor change, possibly made so exposition can be turned into dialogue instead of having Rogers talk to himself. If the name Buddy means nothing to you, it’s probably because you’re most familiar with this guy, who replaced him in the 1979 series (post-Star Wars, cute robot or critter sidekicks became de rigueur):

Not all serials featured sidekicks, but when they did there was a wide variety of characterizations, from the helpless burden who existed only to be put in peril and rescued (or not rescued, as I found to my horror when watching Daredevils of the Red Circle), to young characters who were almost co-leads (Robin in the Batman serials, the Baxter twins in The Phantom Empire, and young Kit Carson in The Painted Stallion all come to mind). On a scale of one to ten Wesley Crushers, Buddy Wade appears to be a competent team player who looks up to Buck and takes his lead from him, but hasn’t so far shown much personality of his own: more information is needed.

From a production standpoint, there’s no question that modern viewers will need to adjust their expectations. I like the way miniatures and stock footage are combined with newly-filmed scenes to create a story, and some remarkable effects are achieved with limited resources, but suspension of disbelief is definitely required. In fact, Buck Rogers wasn’t at the cutting edge even when it was made: recall that 1939 was the release year for such lavish productions as The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind. But serials, even relatively expensive ones and even at big studios like Universal, were at the low end of production: they were made quickly and with small budgets, and their most distinctive characteristic as a genre is their recycling of studio assets. Sets, props, costumes, stock footage, and music were liberally borrowed from previous productions as cost-cutting measures. As an example, “Tomorrow’s World” is full of background music already familiar to me from the Flash Gordon serials (also produced by Universal), drawn from the studio’s extensive library of recordings. (It’s worth noting that Charles Previn, great-uncle of André, is credited as “Music Director” rather than “Composer.”)

Likewise, the cast is made up of contract players, many of them familiar faces to serial fans. I’ll get to them as we go, but let’s start with the marquee name. Leading man Clarence “Buster” Crabbe (here billed as “Larry”) appeared in dozens of Western and adventure films, but it was serials that made him a star. An Olympic swimmer and gold medalist, Crabbe had begun acting almost as a lark and a way to earn money for law school, only to find himself cast as Tarzan and Flash Gordon, among other parts, before appearing as Buck Rogers. (At least as Rogers he could leave his hair dark: it was dyed blond for his appearances as Gordon.) I have elsewhere written that “Flash Gordon isn’t a role to be acted: it’s a role to be embodied, and Crabbe has the physique and movie-star looks to pull it off,” and that continues to hold true in Buck Rogers. It remains to be seen how much depth Crabbe’s portrayal of Rogers has, but in other performances the actor was capable of an easy-going naturalism that fit perfectly the type of all-American red-blooded man who didn’t start fights but wasn’t afraid to finish them. (Although he had little formal training, Crabbe claimed to have learned most of what he knew about acting from watching Gary Cooper on set.)

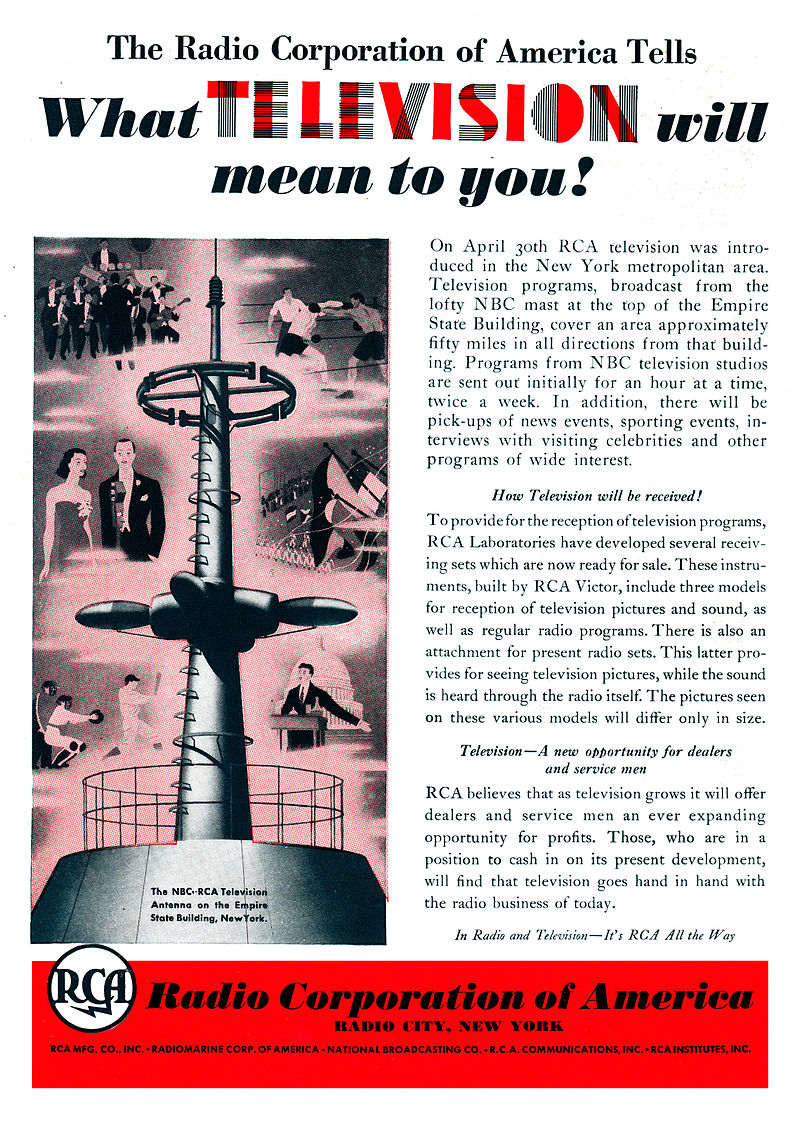

Finally, there is Buck Rogers‘ now-antiquated vision of the future. The jetpack-raygun-tailfin aesthetic of the “Gernsback continuum” is the real draw of Buck Rogers, delighting in the wildest speculations about future technology and dressing its characters accordingly. Quasi-military space helmets and art-deco flourishes are the order of the day, and whatever the merits of the story, it’s the gadgets that audiences of the time came to see. I suspect we’ve only had a taste of Buck Rogers’ futurism in this chapter, but it’s a revealing one. In addition to disintegrator rays and transporters, we’ve gotten a glimpse of a 1939 skyline in twenty-fifth century apotheosis, complete with orderly lanes of flying traffic, the sort of thing seen in Metropolis and Things to Come (and later homaged in the Star Wars prequels), but it’s the television screen on which we view it that is of greater interest to me.

Television appears to have been an endless source of fascination for filmmakers in the 1930s, and unlike many of the fanciful technologies that feature prominently in the period, it was just around the corner. Early demonstrations had proven television’s feasibility throughout the 1920s and ’30s, and by 1939 commercial sets were becoming available for early adopters to watch brief experimental broadcasts. It wasn’t hard to believe that when television became widely available it would change the world as thoroughly as radio had. (In many ways it did, of course, but not in the ways people expected.) Rather than a medium for communicating news or entertainment, however, in Buck Rogers, as in other films of the 1930s, television takes the form of a magical remote-viewing window.

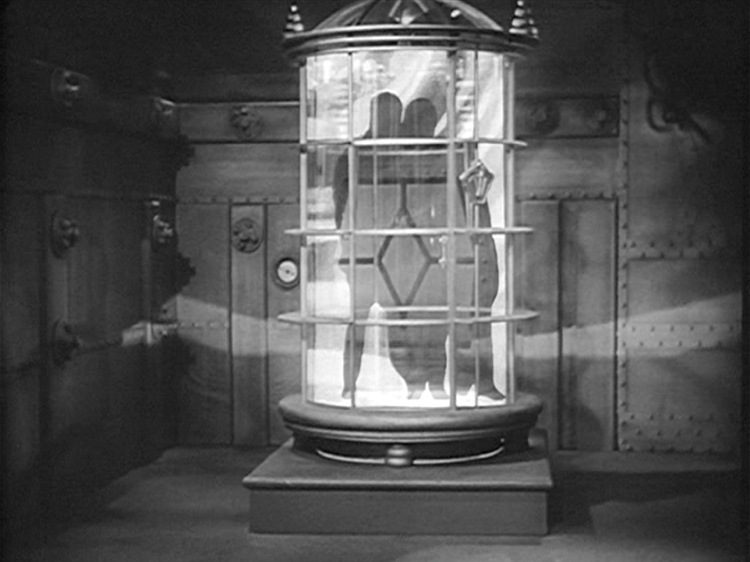

The scene in which Dr. Huer looks in on Kane’s headquarters is typical: there is no suggestion that an Earth spy planted a hidden camera there; rather, the television screen allows the viewer to see wherever he wishes, free of the need for a bulky film camera, granting an incredible power to whomever wields it (the periscope-like viewer Wilma Deering is shown using suggests an extremely powerful telescope, perhaps, but one that is able to see into enclosed rooms is truly miraculous). The power of surveillance is not to be overlooked, certainly, as our increasingly miniaturized and ubiquitous cameras have revealed, but in its first few decades the power of television was one of projection–of image, of word, of emotion–rather than detection. I especially appreciate the picture-in-picture effect when Kane looks through his television at his “living robots” while Huer is watching him. Makes you wonder if someone is looking over your shoulder while you’re watching it, doesn’t it?

That sets us up for Chapter Two, “Tragedy on Saturn,” in which I predict the exposure to cosmic radiation in space will have given superpowers to Buck Rogers and his crew. Maybe Wilma Deering will become invisible, and Buddy able to burst into flame; will Buck gain stretching powers, or perhaps turn into a rock-like thing? There’s only one way to find out: Tune in Next Week!