“Maybe now’s not the best time to do this.”

The overall shape of this season makes more sense now: the slowness of the last two episodes feels more like a deliberate strategy, as most scenes in this hour are about characters going too far, too fast; and what’s felt like Pizzolatto getting off on being withholding gets expressed in the final scene as the mental landscape of a man who can’t remember the most important event in his life. All through the episode, people make a move they shouldn’t, speak when they should stay silent, make something happen before anyone’s ready.

That starts right away with a 1990 scene of Wayne, Roland, and the reinvestigation team going over evidence, especially a picture Wayne’s certain is Julie Purcell. Roland makes clear that he wants that information kept from Tom Purcell (Scoot McNairy), which Wayne blows to shit about thirty seconds after Tom shows up. Last episode made clear how protective Roland is about Tom, and in this moment, Stephen Dorff makes his sense of betrayal clear, something that plays all the way to the final scene.

Near dead center in all seasons of True Detective is a balls-out action sequence; season one had the eight-minute tracking shot, season two had the raid, and it’s only a few minutes before we pick up where the last episode left off, with Brett Woodard (Michael Greyeyes) full-scale assaulting the men surrounding his home, and a few cops too. Prefigured by the photographs on the wall in 1990 (with the bone-dry comedy of a card reading “Woodard Altercation” below them), it doesn’t have the technical accomplishment of season one or the chaos of two, but it’s more brutal than either, with the first guy shredded by the Claymore mine and Woodard firing headshots everywhere. (“I don’t miss unless I mean to” are close to his last words.) When Wayne has to kill him, it’s as painful as it is necessary, a revelation of the fear Wayne always lives, and a sad, sad death for a man who never could find a life in the World.

Even sadder was the apparent decision in 1980 to pin the abduction/murder of the Purcell children on him; as said in 1990, it’s easy to do when your suspect is dead and there’s physical evidence (the boy’s backpack, the girl’s shirt) on Woodard’s property; one more way this episode moves faster than you’d expect is that Wayne picks up right away in 1990 that they had to have been planted. (He also discovers that some 1980 fingerprint records have gone missing.) Ali gives 1990 Wayne a distinct walk here, like he’s being yanked forward into discovering things, and not really of his own will.

Wayne killing Woodard leads to a series of too-far-goings, in the 1980 and 1990 time frames, between Wayne and Amelia. In 1980, she comes to see him at the hospital and won’t take any kind of “no” or needing to be let alone for an answer, and that gets followed by them going home and him initiating (what’s pretty clearly) the first sex between them. It’s a scene that’s incredibly delicate and nearly wordless, as choreographed as the first kiss in Near Dark, both Ejogo and Ali playing not shifting layers but shifting moments of desire, realization, fear, aggression, defense, evasion, and acceptance. (Pizzolatto directs this as simply as effectively as it could be, with a lot of attention to body language and the space between those bodies.) I appreciate the old-fashioned touch of the two of them going into the bedroom and Ejogo closing the door to end the scene; this moment is for them, not for us. (It echoes the fully-clothed scene between Rachel McAdams and Colin Farrell last season, also about intimacy rather than the audience’s voyeurism.)

Moving to 1990, we get a scene that echoes last week’s fight between Amelia and Wayne, a tense dinner between them, Roland, and his girlfriend (not wife, which will matter later), with Amelia wanting to talk about the case, Roland OK with that, the girlfriend curious, and Wayne wanting none of it. The scene leads to another argument at home, this one ending not with sex but with storytime in bed with their kids, another way in which the conflicts between them never get (and most likely never got) resolved, just became something that the two of them lived with, accepted as part of their lives. (What can you live with? may be the theme of this season.) That kind of conflict exists at an almost musical level between the actors; one of the pleasures of the Amelia/Wayne scenes has been catching the different speech rhythms of Ejogo and Ali, and how they play off each other. (In the Fight Club commentary, Brad Pitt notes how he and Edward Norton have different rhythms, and how he and Claire Forlani fell too much into the same rhythm in Meet Joe Black.) The counterpoint creates a sense of two distinct personalities and how they’ll never come together. Sounds pretty good too.

Scoot McNairy gets some big, big moments here. From his first scene, Tom is never not desperate; the only question is how far down that desperation is. Right away in this episode, seeing for the first time a picture of his ex-wife dead in Vegas and then catching a glimpse of maybe-Julie (“Who’s that?”), he starts to lose control of that fear. A few scenes later, in front of the cameras and microphones, making an appeal to Julie, the fight between his hope and desperation can be seen and heard in his body and voice; it’s a demonstration of what Bane meant in The Dark Knight Rises that there can be no true despair without hope. (One thing this season has used well is McNairy’s facial-hair acting. Without it, he looks so much younger, and defenseless.) And then, when almost-certainly-Julie calls in to the police hotline and he has to listen to a message disowning him, it’s crushing, a three-scene arc that’s left him even more alone than before, and quite possibly a suspect.

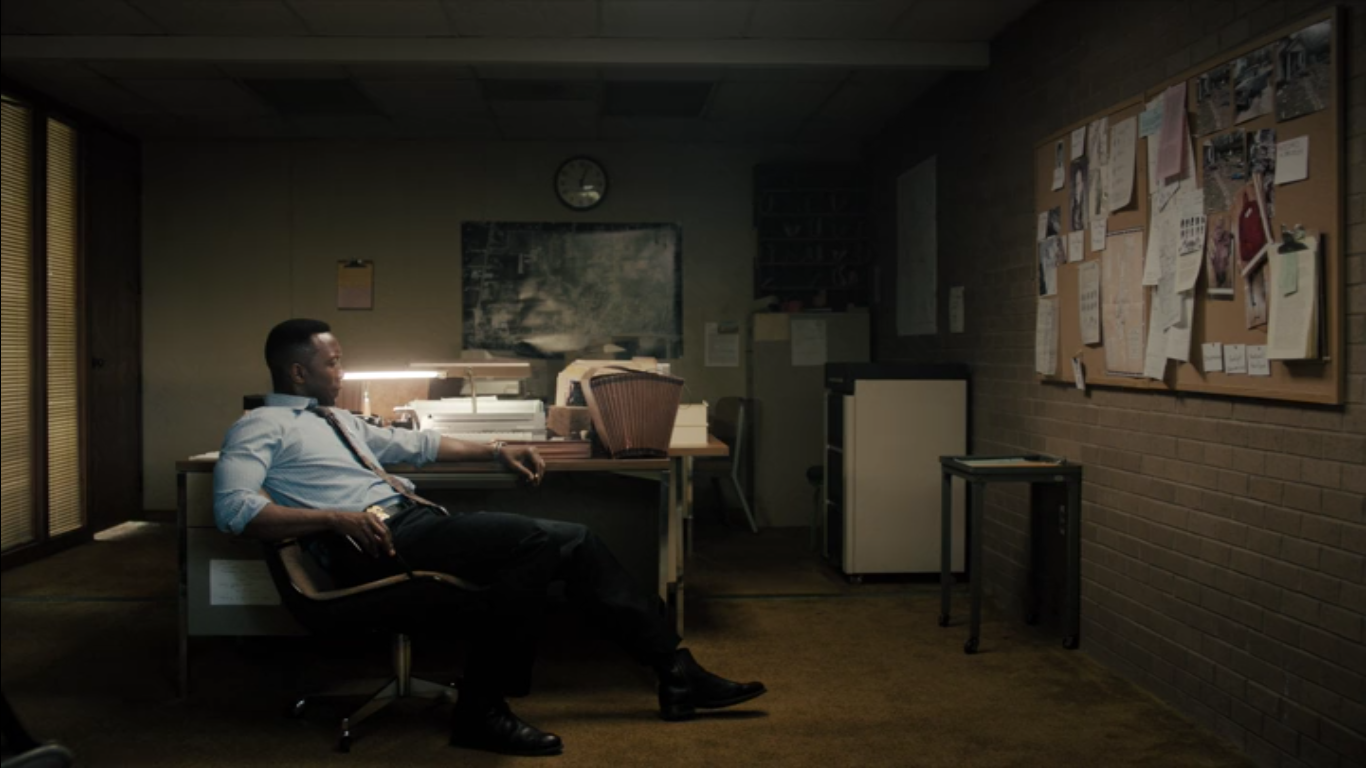

If you want to end your show with Warren Zevon singing “Desperadoes Under the Eaves,” when your two main characters are actually under the eaves, well, you better have one hell of a sequence leading up to it, and True Detective delivers: with over half the season done, Wayne and Roland meet in 2015. (Older Roland gets a great introduction.) In contrast with everything else in this episode, this happened too slowly: Wayne and Roland have not seen each other since 1990, and it’s clear that’s because they killed a man, most likely Dan O’Brien. (Roland doesn’t want to say his name if he can help it.) This was the act that derailed their partnership and both their lives; Wayne’s losing his memory but Roland may be the more damaged one, drinking heavily, rejecting the company of anyone except dogs. Wayne reveals (or possibly falsely claims, but I read him as sincere) that he can’t remember what they did, and that makes the first four episodes play differently in retrospect. They’ve been the fragments of Wayne’s memory that he’s allowed himself to keep, a defense against a self-inflicted trauma, the only story that’s left to him. When Roland decides in the end (and Dorff plays him coming to that decision slowly, and so well) to team back up with Wayne and join the rereinvestigation, not gonna lie, I had a big stupid grin on my face. The Old Guys get the band back together for one last gig, and of course perhaps rock’s greatest singer of loss, aging, and despair should play us out: “heaven help the one who leaves.”