Three seasons in to True Detective, Nic Pizzolatto has not gotten one bit less ambitious, or, in the best way, more inventive, continuing to use the basic plots of crime fiction as a way to explore larger questions and obsessions. In superficial terms, this is so far a replay of the first season–two detectives in the American South, a cold case of abduction/ritual killing, a triple time frame–but the theme and presentation are much different. Strip away everything else from the first season and the core is about two men trying to find a reason to live in the world; so far, this season is about memory in all its forms.

This review will be as SPOILER-free as I can make it, but some stuff might slip out.

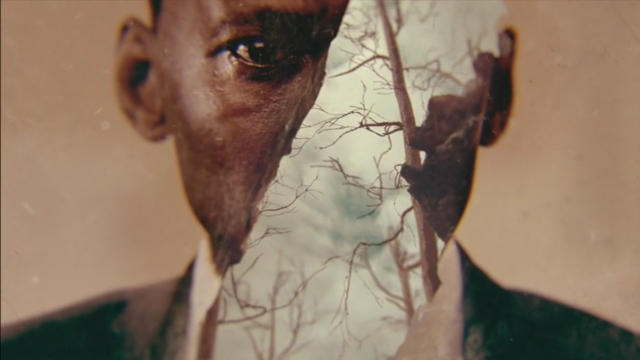

By the end of the first episode, the plot elements have all been set up. In 1980 Arkansas, Detectives Wayne “Purple” Hays (Mahershala Ali) and Roland West (Stephen Dorff) investigate the disappearance of two children. In 1990, Hays gives a deposition about the case (which leads the kind of end-of-first-episode revelation that makes for good TV) and his wife Amelia (Carmen Ejogo) publishes a book about it. In 2015, his wife now dead and his memory failing, Hays gets interviewed for a true-crime series (called True Criminal, which is either Pizzolatto just getting way too cute or leaving in a placeholder) whose producer might have an additional agenda.

So far, so much like season one, but the differences are obvious from the first ten minutes. This season, at least in these episodes (Jeremy Saulnier directed them and then left the series), takes a much more flexible approach to the different decades, slipping between them within a scene, letting the dialogue overlap, using visual rhymes to make the jump. This is the most direction True Detective and Saulnier have done, and it’s jarring at first, even if it doesn’t push into the style-trumping-substance of Jean-Marc Vallée’s Sharp Objects. Similarly, T-Bone Burnett’s score is much more omnipresent in these episodes. The music and direction create a different feel for the series, and the clue as to where this season goes: we don’t see the events but the memory of the events, the story of the events.

What’s promised so far–and we’ll see if this continues–is a work about the ways in which events turn into stories. There are little stories all around these hours; it’s a great Pizzolattan detail that we jump back into 1980 with the line “it was the day Steve McQueen died.” (Hays pours one out for the man when he hears that. Rightly so.) Hays was a LRRP (Long-Range Reconnaissance Patrol, pronounced lurp) scout in Vietnam, and West tells a story about that. The events of the abduction and investigation have turned into files, depositions, court cases, books, it’s becoming a TV show in 2015, and most of all it turns into Hays’ memory, and that memory is failing. Early in “The Great War. . .,” Amelia reads a poem from a favorite storyteller of mine, Robert Penn Warren, saying “What is love? One name for it is knowledge.” When the knowledge fails you, what happens to what you love?

It’s a good, disturbing theme, something that calls up the inevitability of mortality and possibly the necessity of forgetting, of moving on. (West isn’t present in the 1990 scenes, and one line about him–“He’s done well for himself”–suggests he was able to do that.) Most of its power comes from Ali, who is nothing short of amazing so far. It’s a great technical performance; not just his look but his voice instantly identifies the time frame, which is necessary when there are so many voiceovers. More than that, Ali plays every scene differently depending on who else is in it: Ali and Dorff have a good, lived-in chemistry that’s less talkative but no less compelling than Rust Cohle and Marty Hart (and Dorff gets a one-word reaction in the second episode that’s the funniest thing in both hours); Ali plays more openly with Ejogo, two black people in Arkansas able to talk about it, even if only for a moment (their first meeting is great; there is no question that these two could end up married. Saulnier blocks it perfectly, letting them stand just a few inches closer than they should); and Ali’s reaction when he’s alone and sees a corpse is devastating and devastated, finally able to fully express himself because no one can see it. His 1990 self is much harder and closed off than his 1980 self, and his 2015 self is all fear and searching. (There’s a moment a few minutes into the first episode that’s so scary, and it’s all down to Ali’s voice and Saulnier’s editing.) Ali is beautiful in a way that looks like sculpture, and that’s a benefit for Pizzolatto’s kind of drama, where the characters have to be outsized and nearly iconic.

Hays and Amelia have both learned how to be black people in the South, and Saulnier/Pizzolatto wisely let that be a matter of attitude and gesture rather than anything overt. (Having the True Criminal producer let loose a bunch of academic jargon to place her as Not Getting It is way off base, and feels like a Statement rather than a story.) Hays’ reactions tell part of that story; so do the reactions of others–watch the slowness of pair of cops when Hays orders them to start canvassing. Saulnier includes a lot of other detail, not just racial relations: watch how, in the long journey the children take before they disappear, he catches details of the houses, fields, and people of this Arkansas town; or look at the haunting shot of a school bus in the middle of the street with no one getting on it. If the direction pushes away from realism to the edge of artiness, that makes sense for a season about events that push into stories, and stories that fade.

True Detective has never been a perfect work, and that’s because it’s never been a work of someone who’s content to do what he did before. If there’s a unifying theme to all three seasons, it’s loss: of family, of time, of a state, of memory. This season already has a distinct feel and structure to it, and these episodes make me want to see more. On that most important level, they’ve done their job.