Review of minutes 1-58: here, in the tenth hour of Nic Pizzolatto’s television works, we get the strongest sense of his identity as a writer. It’s there in tonight’s first four minutes, a stunning monologue by Vince Vaughn’s Frank about being locked in the basement for five days as a child. It’s there in the second monologue, near the episode’s midpoint, from Ray’s (Colin Farrell) ex-wife, as she says he was once a decent person, but wasn’t strong enough to stay decent after her rape. Pizzolatto isn’t really a noir or a crime writer; his true dramatic ancestor is Eugene O’Neill.

Like O’Neill, Pizzolatto’s interest is in mostly damaged men and a few women, equally damaged. Damage is like original sin; you don’t call it on yourself, you incur it simply by being in the world, usually from your family. We meet Lolita Davidovich as Paul’s (Taylor Kitsch) mother or stepmother and we immediately sense a history he cannot escape; we hear from Ani (Rachel McAdams) that of the five children in her home, two are dead, two are in jail, and one is her. The power of the first season’s ending was very much the power of O’Neill’s ending, the sense that we have to fight, and not so much fight against evil as our own brokenness.

Pizzolatto shares O’Neill’s feel for the modern world as a place of wonder and horror, and that’s shaped both seasons. The Louisiana of season one hadn’t fully caught up to modernity and that allowed us to see so many unique things. The LA of season two is fully modern, and fully strange because of that. I don’t get the feeling here of so much LA fiction written or filmed by outsiders of “crazy, amirite?” but something deeper. Pizzolatto’s Los Angeles gets its strangeness because it’s the thin edge of the modern world, always developing new things. Here it’s the City of Vinci (“Toward Tomorrow”) with its 95 residents and millions of gallons of toxic waste, often with children playing in it, often visible in the background as people talk. The overhead shots of the first episode evoked Koyaanisqatsi; this episode looks like the ground-level Powaqqatsi, with its imagery of the destructive power of capitalism.

Realizing the O’Neill connection made a lot of the language, character, setting, even direction click. Pizzolatto’s language has much of O’Neill’s bluntness, what he called “the native eloquence of us fog people,” the feel of truths stated simply because they cannot be escaped. We’re not used to seeing this on television’; really we’re not used to seeing this anywhere in the last few decades. “Literary” writing has come to mean clever jokes and references, and yes I mean you Aaron Sorkin. “You’re a bad person and you’re bad for my son” and “fundamental difference between the sexes is one of them can kill the other with their bare hands” would both work on a stage in 1955, especially as part of an audience-facing monologue. There’s the theatrical sense that the characters aren’t entirely interacting with each other, but presenting a layer of their inner thoughts to us, and I suspect having gotten the basic setup out of the way in the first episode allowed Pizzolatto to give the language more free reign here. (Director Justin Lin backs this up by continuing his focus on faces, and again often shot straight-on.) There’s also the very theatrical effect of coming back to the same bar to end each episode with a Frank/Ray meeting. If you can accept it, it’s bracing.

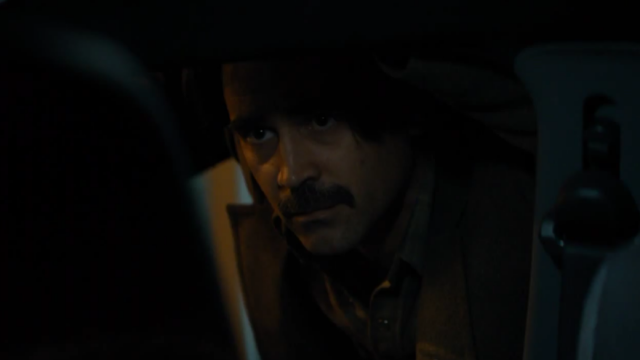

You need a level of, for lack of a better word, weight in the acting to bring this off. They have to convey the entire history of their characters in their actions, because without that, the dramatic language becomes overdramatic. So far, Vaughn is in the lead here; it’s not just his face, but even his walk conveys a need to be careful. It feels like everyone watching him (including me) expects him to burst into violence at some point; when he crushes a pair of eyeglasses in his hand, the tiniest piece of his history seems to be leaking out. Farrell and McAdams are close behind although not as good; it’s good to get them in a car and talking together Rust-and-Marty style. Farrell lands the O’Neill feeling hard, though, when he yells to his ex-wife that he had a natural duty to kill her rapist, one more way a pre-modern value gets crossed up in the modern world.

As for the plot, it ticks forward here in a necessary way; we aren’t missing out on the pleasures of a procedural, as the characters move to different settings (a cosmetic surgery clinic, a nightclub, a Hollywood apartment) and pick up clues. We also get the complication of Ani and Paul effectively working as deep-cover agents with and against Ray, and Ray knowing it. (“How compromised are you?” is another O’Neillish line.) The “intimacy” that Pizzolatto talked about as a major component of season one isn’t there yet; so much of this episode shows how Ani, Ray, and Paul can’t communicate with each other. But they might learn how.

Review of minute 59: True Detective is at its best when it’s at its strangest, and the masks in the Hollywood apartment have something of the feel of the Yel–FUCK.

Reviews for this season of True Detective will appear weekly Sunday night/Monday morning.