wallflower: By the time Schizopolis was released, I’d lost track of Steven Soderbergh. For a brief while, he was one of those artists (David Mamet was one, Tori Amos was another) that I felt like I was growing up with. I’d seen sex, lies, and videotape not long after it won the Palme d’Or at Cannes, saw Kafka in its brief release, missed King of the Hill, and caught The Underneath on video(tape). I’d read his screenplay/diary for sex, lies and enjoyed it; what came through in the diary and in all of his work was that this was an intelligent man who was constantly learning his craft. The sex, lies diary is filled with all sorts of fascinating details about working with actors, producers, Cliff Martinez, screenplays, film stock, lighting, and lenses. Soderbergh came across as someone with a lifelong fascination with film in the way that a writer with a distinctive voice (Joan Didion, say) has a lifelong fascination with sentences.

I’d enjoyed all of his films, although I can’t say any of them blew me away. There’s a feeling in those three that I was seeing things almost but not quite the way I’d seen them before; looking back, it’s because Soderbergh was willing to tweak the basics of filmmaking, present things just a little differently than anyone else. The long, wordless scene near the end of sex, lies with Spader and MacDowell (in the diary, Soderbergh wrote something like “tomorrow is the scene on the couch. I have no idea what will happen”), the slow-motion chase up the hill and the rectangular incisions into heads in Kafka, the greenish present-day scenes in The Underneath, all of these are things that I hadn’t seen before, but done so simply and elegantly, it felt like I should have. Soderbergh felt like a director from an earlier time, somehow. So, when Schizopolis showed up at the local art-house cinema for the typical one-week engagement, I was intrigued–not “oh wow, new Soderbergh!” but “hm, what’s he been up to?”

The Narrator:Schizopolis is the first Soderbergh I ever watched. At that point in my life, I was basically doing what the Criterion Collection told me to do, so I figured this looked funny enough, and it had Criterion behind it, so I’ll give it a shot. At that point, I just thought it was hilarious, not knowing anything about its context, coming after Soderbergh’s commercial bottoming out and perhaps especially his divorce with actress Betsy Brantley (the female lead of Schizopolis) Having recently revisited The Underneath, I noticed more than ever how bitter and mournful it is. You get the sense that Soderbergh was trying to make something personal out of impersonal source material, and the scenes with Peter Gallagher and Alison Elliott during their doomed marriage are particularly painful knowing that Soderbergh likely went through those scenes himself. We never see the happy times in their relationship. The only time they can tolerate each other is when Gallagher is on a winning streak, and otherwise they’re defined by their passive-aggression towards each other. By the time the heist comes along, you can kind of tell that Soderbergh has lost interest in the movie, because there’s nothing there for him to connect to anymore. He talks about, in an interview on the King of the Hill Criterion, how he remembers prepping Schizopolis in the time he should have been making The Underneath, and that shows on both Underneath (which I still think is a tremendously underrated film) and Schizopolis.

wallflower: Although The Underneath was well-made, you’re right about its loss of filmmaking energy. In this part of his career, Soderbergh hadn’t come to terms with making a genre movie; comparing it to other 1995 films, it doesn’t have the spin on genre that David Fincher brought to Seven or the absolute commitment that Michael Mann had in Heat. (Bryan Singer, in The Usual Suspects, had both.) In addition to his divorce (which surfaces so strangely and powerfully in Schizopolis), Soderbergh was still an experimental filmmaker who couldn’t find anything to experiment on in The Underneath.

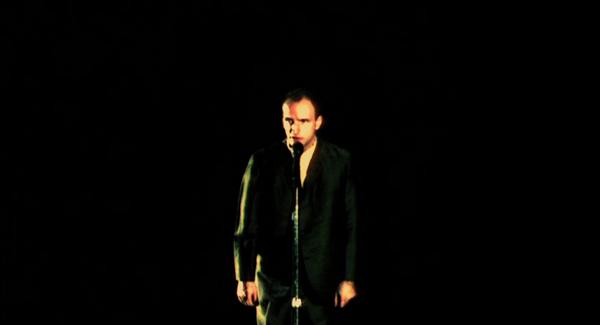

So, it’s 1996. I got my ticket and took my seat; there were maybe eight people in the theater with me. (To this day, I’m pretty sure that everyone who saw Schizopolis in the next few years saw it because I recommended it, or one of the people I recommended it to recommended it, or one of them–I’m Patient Zero for the Schizopolis contagion, is what I’m saying. Soderbergh owes me.) On the screen, Soderbergh himself walks out and introduces the movie and insists on its importance–”a sincere belief that the delicate fabric that binds us all together will be ripped apart, unless every man, woman, and child sees this, and pays full price, not some cut-rate bargain matinee deal.”

That’s strange enough, and funny enough. What hooked me, and keeps going all the way to the end, is what Soderbergh does with film. There’s a demented calliope going on under the speech like a Sam Raimi movie. Soderbergh walks leaning backward, like he’s Hitchcock walking up to his own outline. The camera doesn’t zoom in on him; Soderbergh announces “turn,” looks up like he’s about to be teleported, and the image goes flying downward, catches the lights, and comes back in from the top. (The camera operator is simply turning the lens attachment.) And the lighting makes his suit look like some kind of NASA-developed material.

The spirit of all of these things, and it continues for the rest of the movie, is why the hell not? Usually that spirit will get you a boring, tonally incoherent mess. Soderbergh, though, has such a devotion to the craft of filmmaking that his effects are genuinely weird and memorable as David Lynch’s, and done entirely with the language and mechanics of film. The effects were memorable for Soderbergh, too–for example, when Fletcher Munson transubstantiates into Dr. Jeffrey Korchek, it’s signaled by four shots of Munson from the cardinal points–front, left, back, right. Soderbergh liked this enough to use it in Solaris. Narrator, what are some of your favorite moments of filmmaking here?

The Narrator: I love how Soderbergh utilizes cinematic concepts usually there to provide context to the actions in the film to further obscure any point the movie is making. Throughout the film, Soderbergh hints to the audience about explaining at least some of the shit going on, and then uses those devices to make the film seem even more unintelligible, whether it’s the “busted decoder ring” of the third act (more on that just a little later), the meaningless patter of Man Being Interviewed, or the way the film’s abuse of language keeps shifting. But perhaps even more ingenious than the film’s seemingly impenetrability is how well-structured it actually is. The first act is full of bizarre details which pay off in unexpected fashions later. Even something as seemingly absurd and random as Munson’s trash bin, which plays muzak when paper is thrown into it, is a hint at the coming appearance of dentist/muzak enthusiast Jeffrey Korchek. And I swear, until this viewing, I didn’t realize that the guy with nothing but funny stories to tell Korcheck while they play golf (the golf ball hits Munson’s lawn in all three acts) is a direct echo of Munson’s coworker in the first act, who has nothing but bad news to report to Munson. It’s a tightly-packed script disguised as something that seems like it was written over a weekend.

What I love most about the film (besides how fucking funny it is) is its three-act structure. Possibly the most important thing Soderbergh took from this movie is that. Each act here explores a different aspect of the film and the characters, not necessarily in narrative order. The first act is Munson, the second is Korchek, and the third is Mrs. Munson (to give a few other Soderbergh examples, The Informant! goes Mark the family man-Mark the whistleblower-Mark the compulsive liar, and Side Effects is Rooney Mara-Jude Law-Catherine Zeta-Jones), with each act presenting a new lingual barrier. The first shows language stripped down to its very basics, with descriptions of the words being spoken taking the actual words’ place (“False reaction indicating hunger and excitement!”). In addition, we see local exterminator Elmo Oxygen seducing housewives with a language of his own creation. Then in the second act, with the switch from Munson to Korchek, language is stretched to the very brink of its abilities. Korchek falls madly in love with Attractive Woman #2, to whom he writes a love letter which alternates between failed poetry (“I may not know much, but I know that the wind sings your name endlessly, although with a slight lisp that makes it difficult to understand if I’m standing near an air conditioner”) and wildly inappropriate musings (“I know that if for an instant I could have you lie next to me, or on top of me, or sit on me, or stand over me and shake, then I would be the happiest man in my pants”). Korcheck treats his patient to dental-related puns, which range from slightly groan-inducing (“Be true to your teeth, and they won’t be false to you”) to outright absurd (“I may vote Republican, but I’m a firm believer in gum control”). At one point, a man with a gun approaches Korcheck and demands “8 hours, your brother, $15,000”, which devolves quickly into a debate on word order. And when Korchek breaks it off with Mrs. Munson, she delivers a speech so powerful that it’s easy to ignore it’s complete nonsense, comparing them to a “rag with a stain you can’t get out” and a “piece of rotting fruit on a windowsill”. When the third act comes along, it serves as a half-functioning decoder ring of sorts. When the third act comes along, we can finally hear what Mrs. Munson was actually saying in the first and second acts, but the dialogue of the two Soderberghs has been dubbed into a foreign language. Each act serves as a subversion of the last, effectively keeping the audience on its toes at all times.

Wow, that got much longer than I expected it to. Anyway, we’ve discussed it as filmmaking, so let’s discuss it as a comedy next. What are some of the things that made you laugh the most in it?

wallflower: For me, the effectiveness of the gags comes from the precision. Note that, for example, the muzak from Munson’s (MUNSON!) garbage can doesn’t just foreshadow Dr. Korchek, that’s the same muzak that plays in his office. (Lost Highway did a variation on this gag.) The gibberish spoken by Elmo Oxygen, Exterminator (and other things), is an exact language, and we’ve all had fun translating it (“jigsaw”=”OK”; “nose army”=”hello”; “smell sign”=”goodbye”; there are others), and all the players deliver it just like conventional speech. Everyone nods along and reacts the same way at both versions of Lester Richards’ funeral, whether the priest is being honest (“look at Lester’s wife. She’s a babe.”) or just giving the standard speech. You noted the three-act structure; Soderbergh goes farther than that, indicating each act by a brief scene with the corresponding numeral. (This movie is about as brief as Fargo and just as economical.)

Probably the most consistently funny part of Schizopolis is Elmo Oxygen. He’s the equivalent of Desmond in Lost; the rules don’t apply to him and he can shift between languages and realities at will. After seducing (and photographing) the wives of T. Azimuth Schwitters and Nameless Numberhead Man, Elmo₂ gets approached by a rival set of producers (“oh, this is not our first project together. These are my friends. I trust them.” “Friends.” “Trust.” “Mm.”) and hijacked out of the movie. (Typically precise and inexpensive gag: we hear the car with Elmo₂ drive off and the sound fades, because, as we see, the guy with the boom mic isn’t moving. Also, Soderbergh is right there directing and looks puzzled.) He can even shift between layers of meaning in a single scene: “all right, if metaphor is too complicated for you, I will just say it: the little PA in the black, the one with the clogs, I would like to fuck her, please.” Having said all that, my favorite scene is the new action-oriented Elmo₂ charging into a mattress store and ripping off the tags. “Total fuckin’ disregard,” as he says, just before an employee tackles him.

As we’ve demonstrated here, this is a marvelously quotable movie, right up there with The Big Lebowski. In both cases, there’s a great sense of poetry and rhythm to the language that requires much precision by the actors; when we quote them, we don’t just quote the words, we quote the pauses and inflections too. Say “I believe so strongly in mayonnaise” right now, and you will say it like Elmo₂. It’s the antithesis of the kind of shaggy, improvisational comedy of Team Judd Apatow, it’s the kind of chaos and lunacy that can only come from its precision and tight construction. (Well, OK, Munson jerking off in the bathroom could be in an Apatow comedy.)

I am admittedly still reeling from the thought of this being someone’s first Soderbergh film. You mentioned seeing the three-act structure in many of his subsequent works; what are some other ways Schizopolis has affected your view of Soderbergh?

The Narrator: Well, I’m definitely more susceptible to easter eggs in his other movies, whether it’s cast members from this (I love how Mike Malone, or T. Azimuth Schwitters, appears in The Underneath dressed exactly like Schwitters, giving the impression that before Eventualism Schwitters frequented Texas roadhouses) or little nods to it (my favorite is how Reuben suffers a “myocardial infarction” at the beginning of Ocean’s Thirteen, the same condition Lester Richards succumbs to at the beginning of this). On a larger scale, this serves as something of a Rosetta Stone for the rest of Soderbergh’s work. When Lifetime eventually creates a movie of Soderbergh’s life, it should be called Language is Slippery: The Steven Soderbergh Story. So many of his movies focus on what language does and how it can bent in ways both good and bad. In sex, lies, and videotape (referenced in the crudest fashion possible in Schizopolis, with an Elmo Oxygen sex tape), Peter Gallagher spends much of the movie making excuses for himself, to his wife, to his old friend, to his mistress, even to his boss (the reason he’s presumably fired at the end, Soderbergh explains, isn’t because cheating is bad, but because worming your way out of meetings in order to cheat is bad for your job). The lead characters of King of the Hill, Side Effects, and The Informant! spend the movie building a palace of lies which collapses by the very end. Obviously there’s the double-triple crosses of the Ocean’s movies, with the scene in the coffeehouse with Matsui in Twelve resembling a cut scene from Schizopolis reenacted by big movie stars. The Cockney rhyming slang of The Limey runs naturally through the movie until it explodes in a hilarious scene with Bill Duke. Dr. Kelvin in Solaris stays quiet out of grief, remaining tight-lipped even as his patients spill all the beans. The strippers in Magic Mike stay quiet so that the audience can project an image onto them (in sharp contrast to Sasha Grey in The Girlfriend Experience, whose image is based around conversation first and fucking second). Gina Carano in Haywire stays quiet because who needs words when your foot is on someone’s throat? And there’s few things scarier than the involuntary loss of language, as shown in Contagion (no wonder Soderbergh himself makes a vocal appearance in it, as Patient One of the virus), with one of those few things being the spread of misinformation, also shown in Contagion. Language has been on Soderbergh’s mind since the very beginning, but Schizopolis put his emphasis on it into a whole other gear.

Anyway, I think it’s about time we discuss the actors here. As you mention, David Jensen is hysterical as Elmo Oxygen (my favorite Elmo moment might be his subdued relief/anger after the producers take him away from the film: “Fuck this mayonnaise, this shit! I’m outta here! Fuck you!”). Soderbergh does great as both Munson and Korchek, subtly shifting body language and speaking patterns as he changes characters (on the DVD, we see a third, unused Soderbergh character, this one with an afro wig). Eddie Jemison is absolutely hysterical as the constantly desperate Nameless Numberhead Man, a chubby-chaser concerned about his wife’s increasing skinniness and the feeling at work that he is either the mole or the spy (or maybe both). His delivery of “It’s in his head… and he’s dead!” is almost musical. But special praise should go to Betsy Brantley, Soderbergh’s wife for five years before a bitter divorce, and Mrs. Munson/Attractive Woman #2 in the film. This film was made one year after they separated (they had agreed to work together while they were married), and beneath all the silliness, you can see the weariness and sadness pretty clearly. Brantley gets much of the third act to herself, and she gets a few big emotional showcases, surprising for a movie which also features fat-lady porn as a plot point. On the first viewings, all you see is something really funny and wacky, and all that good stuff. The more you watch it, the more emphasis seems placed on the mournful qualities, like a tender post-coital conversation between Korchek and Mrs. Munson (in comparison to the bedroom scene with Mr. and Mrs. Munson, which ends with a Gordon Willisy shot of Fletcher trying to unobtrusively masturbate next to his wife) and the final line of the film proper (not counting the “Q&A session” with Soderbergh at the very end). Brantley is so good in this that I hesitate to call her work in this a performance at all.

wallflower: It’s definitely Jensen, Brantley, and Jemison who come off the best of the supporting players. Betsy Brantley is one of the many good actors who’ve been in only minor roles in films (I’d first seen her in 1985, as Jeff Goldblum’s sister in The Race for the Double Helix, which I will never stop telling everyone is the best film ever made about science) that I keep hoping will get a good, juicy role on TV show someday. You’re right about the sadness and even anger in her performance; in Getting Away with It, Richard Lester noted the anger and Brantley said to Soderbergh “if you take credit for that performance, I will kill you.” (I can understand that.) Jemison has a live-wire nerdiness to him; I was surprised when his Ocean’s character wasn’t named Nameless Numberhead Man. He’s exaggerated without ever falling over into stereotype in all of these films, something that The Big Bang Theory never got right. (More likely they don’t want to get it right.) My favorite, still musical NNM line (oft quoted) is “. . .I gotta think about that.” Actually, I’ll give a shout-out to one more: Mrs. NNM, played by Katherine LaNasa. One of the things to, not exactly enjoy, but appreciate about Schizopolis is the way it respects women who are just fed up with their husbands, and in a few scenes and I don’t think with any English dialogue, she brings that across.

Many of us have noted the sadness at the core of this film, and how its true subject is the failure to communicate. It’s worth nothing that David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest came out in 1996 as well, and has a lot in common with Schizopolis. Wallace believed that the older, more classic literary structures were simply inadequate for dealing the modern world (I do not believe this), but that novelists had to do more than present the problems of that world, they had to show solutions as well (I do believe this). Infinite Jest was Wallace’s biggest and best attempt at doing both, at its core a simple story about conscious action and presented in a huge, fragmented, and often insanely fucking funny book. It’s as overtly freewheeling and covertly structured as Schizopolis, and just as much about the failure to communicate; sometimes, when reading Wallace’s work, I’m sure Soderbergh’s film actually belongs somewhere in James O. Incandenza’s filmography of Anti-Confluential Cinema. (Something very much like turning all of Rhode Island into a shopping mall happens in Infinite Jest. In this case, we gave it to the fucking Canadians.) Incandenza is more than a little like Soderbergh–mostly self-taught, relentlessly and restlessly experimental. (Sadly, it would be Wallace who followed his own creation and took his own life. We still miss him.) Wallace and Soderbergh were born less than a year apart, and made their debuts in the late 1980s (Soderbergh with sex, lies, and videotape, Wallace with the novel The Broom of the System); Infinite Jest and Schizopolis are both works of maturing (not mature) artists, both experimental, but neither of them interested in experimenting for the sake of experimenting. Both of them try to answer a fundamental human question: how can I talk to you?

The Narrator: Before we move on, I feel obliged to make some comment about Soderbergh’s commentary on the Schizopolis DVD, which almost acts as a separate film playing over the actual film. It too explores the failure of language, in this case a heated conversation between Steven Soderbergh (playing himself as a pompous, frequently dismissive interviewer) and Steven Soderbergh (playing himself as a pompous, self-obsessed director). To give the reader an idea of the track, one digression starts when Soderbergh the interviewer asks Soderbergh the director if he feels the film’s fourth-wall breaking is off-putting to audiences. Soderbergh the director tells him that his film is not only breaking the fourth wall (when the viewer becomes aware they’re watching a film), it’s breaking the fifth wall (when the viewer becomes aware they’re being watched, by Soderbergh behind a wall two feet behind the fourth wall, while they’re also aware they’re watching a film), before hypothesizing about the possibility of also breaking through the ceiling (his reasoning is that there has to be a ceiling with all these walls involved). He then talks about his plans to make a film which breaks through all those walls (the fifth will be moved back to four feet behind the fourth) and the ceiling, that film being Ocean’s Twelve. There are plenty of other discussions like that during the other 90 minutes of the track, and it is glorious.

wallflower: (during the making-faces-in-the-mirror-scene): “OK, what’s going on here?” “I’m practicing my Oscar speech.” Glorious indeed. Also, I think you’ll find that in the deleted scene with the Afro’d Soderbergh, he’s playing a young Fletcher Munson asking his future wife on a first date. One of Soderbergh’s faces in the mirror graces the cover of Getting Away with It: Or, the Further Adventures of the Luckiest Bastard You Ever Saw, a book Soderbergh wrote just after the making of Schizopolis. (Awkward but necessary segue.) In format, it’s a little like a Wallace work or Soderbergh’s own The Limey, alternating between Soderbergh’s journals of the period and a series of extended interviews with director Richard Lester (A Hard Day’s Night, Help!, The Three Musketeers, Robin and Marian, et al.), plus a bunch of sarcastic footnotes that could have been written by the interviewer from the Criterion Schizopolis.

It makes sense that Soderbergh would be drawn to Lester, and at this time. This was a moment when Soderbergh, after his divorce and The Underneath, was beginning to get his career back, and what looked like a different career. Lester really began his career with his own Schizopolis—The Running, Jumping, and Standing Still Film, something that was as experimental and goofy, yet as elegantly structured, as Soderbergh’s work. (Naked Man on a Bicycle would not be out of place in Lester’s film.) More importantly, Soderbergh regards Lester as one of the great innovators in cinematography–he calls A Hard Day’s Night the beginning of the modern look of films, and Schizopolis was the beginning of Soderbergh shooting all his own films. I know cinematography is a major interest of yours, Narrator, so what did you make of the Soderbergh-Lester conversations?

The Narrator: As far as cinematography goes, probably my favorite moment in the Lesterbergh (as they shall be deemed to save space) conversations is Lester describing a jazz documentary he shot with Robert Krasker (the DoP of Odd Man Out, Brief Encounter, Billy Budd, and The Third Man, the latter two Soderbergh recorded commentaries for). You can almost see Soderbergh’s brain exploding at the thought of his two cinematic heroes collaborating, and no sooner does that happen as Lester brushes it off with a comment about how he “didn’t do a terribly good job”.

I read the book right around when I began doing my Soderbergh series, coming in expecting to be mainly interested by Soderbergh’s diary portions, and finding myself unexpectedly interested in the Lesterbergh portions. You mention Soderbergh being drawn to Lester at this point, and I think it goes beyond even what you mention. By this point, Lester had been out of the film business for five years, following Roy Kinnear’s injury and death on the set of Return of the Three Musketeers, and in the 15 years since Getting Away with It was published, he has not returned to the director’s chair. And much earlier in his career, Lester had too directed a flop which nearly ended his career, the grimly surreal post-apocalyptic comedy The Bed Sitting Room. Soderbergh was still in “exile” at that point, so meeting with a cinematic hero who hasn’t worked in years functioned as a way of predicting his own future and summing up his legacy. You can see him thinking “Is this me? Will this be me?” during the interviews. He’s looking at a friend to determine his own path.

But looking at the interviews on their own, I was quite engaged and interested. It was the number one force behind me exploring Lester’s filmography, which proved to be incredibly helpful in providing further context to Soderbergh’s work in general (you could teach a class on Soderbergh by just showing Petulia). Maybe not Superman III, but the 60s and 70s work (let’s call it the “David Watkin period”) is probably Soderbergh’s biggest influence (there’s one shot in Ocean’s Twelve which is stolen almost directly from A Hard Day’s Night, and I’m honestly not sure if it was intentional or just a subconscious decision on Soderbergh’s part). But if the interview portions exceeded my expectations, so did the diary portions, and I had high expectations for those as well.

(On a slightly tangential note, I was watching the video essay on Lester on the Criterion Blu-Ray of A Hard Day’s Night, and I got a kick out of Lester being credited as “The Man Who Knew More Than He Was Asked” during the credits, which is his title on the cover of Getting Away with It.)

wallflower: Both the interview sections and the diary sections are filled with dense, everyday detail of a filmmaker’s life in the age of industrially produced movies. (By that I mean movies that are made with large crews, high budgets, and interactions with executives. It’s been pointed out by many many people that with the rise of affordable cameras, websites, and YouTube that we may be entering a new and vastly different age of cinema.) It’s deliberately not as well organized but it’s just as fun and informative about this as John Gregory Dunne’s Monster: Living Off the Big Screen, still the best book ever made about the process of making movies. Soderbergh deals with executives, rewrites scripts (including Guillermo del Toro’s Mimic), edits movies, attends film festivals and panels (including the Cannes debut of Schizopolis), confers with actors (or their agents), and wonders if it’s all worth it, and in the interviews with Lester, finds that he went through very much the same thing.

One of the most interesting parts of the book to me, in terms of Soderbergh’s career, is almost a throwaway moment. Soderbergh leads Lester through a discussion of each of his films, and one of them is the 1974 thriller Juggernaut (which, by the way, has possibly the most British cast in the history of ever). In addition to discussing how the stunt crew got continually drunk, they also discuss the quiet character beats and their absence in contemporary thrillers–Soderbergh says that Juggernaut is the film Speed wants to be. (Lester emphasizes that he’s almost always interested in the behind-the-scenes moments off of the main story.) That fascinates me, because Getting Away with It ends with Out of Sight going into production, and you can so clearly see the same kind of attitude all through that.

I consider Out of Sight to be Soderbergh’s breakthrough work. From sex, lies, and videotape through Schizopolis, Soderbergh was a contemporary independent, experimental filmmaker. Yet he always admired most the filmmakers of the 1970s (he’s often cited Jaws as his favorite film), where there wasn’t any conflict between being experimental (or at least difficult) and being popular. On Out of Sight, Soderbergh kept his desire to constantly find new and interesting ways to shoot things–for example, the abrupt shifts in color when Steve Zahn kills someone–but also brought in some great popular material. Yes, there’s elliptical editing; yes, there’s freeze frames; yes, there’s desaturated color. There’s also George Clooney and Jennifer Lopez being insanely fucking gorgeous and charming. It doesn’t for one moment feel like a compromise or selling out, because for those 1970s filmmakers, like Lester, that were such an influence on him, the virtues of “independent” and “studio” films were never in conflict. Out of Sight began the next great run of Soderbergh’s career; it would continue all the way to Behind the Candelabra and his (HA HA HA HA oh God I can’t even type this with a straight face) “retirement.” (Really, all that’s happened is that Soderbergh has realized that the producers he wants, and the audience he wants, are now on television.)

The Narrator: What I love about Soderbergh is how he’s managed to keep making, for lack of a better word, personal films, studio or no studio (he got a major studio to finance his very uncommercial Michael Curtiz homage, after all). Even something like Erin Brockovich (which was made right as he was fighting his way back into Hollywood, so he had to give up something to make it) has distinctly Soderberghian touches (I’m thinking of the husband of one of the victims impotently raging at the PG&E factories, shot like a deleted flashback from The Limey). His time spent in the wilderness in the diary portions seems to have informed his mission statement from then on; “I’m doing it on my own terms”. You mention the Mimic rewrites (funny enough, in the Mimic commentary, del Toro remembers a much more positive conversation with Soderbergh about his rewrites than Soderbergh does), but perhaps even more important is his experience writing Nightwatch, a mediocre, mostly forgotten serial killer movie. He talks in the diaries about Ole Bornedal (the film’s director) meddling with his script and taking out things that worked well, causing him to admit that he now empathizes with Lem Dobbs (the writer of Kafka, who would later object to Soderbergh’s treatment of his script for The Limey). I’ve watched that movie twice (such are the lengths one goes for an obsession), and I’ve yet to find anything close to Soderberghian, or really anything of feeling at all. Unlike Mimic, he’s actually credited for Nightwatch, and it’s no wonder he mostly stopped writing soon after (since then, he’s written three scripts, two for himself to direct and one for his 1st AD/producer Gregory Jacobs, under the pseudonym Sam Lowry, previously used for The Underneath). And then there’s the deal with Toots and the Upside Down House, a Henry Selick movie which ended up never getting made, so that Selick could move on flop in a more pronounced manner with Monkeybone. Soderbergh talks about the endless hassle finding a distributor for Toots, and you can see him becoming the director he would be now (and whenever his sabbatical, which is what he’s calling it now, comes to an end). As a whole, the book functions as an origin story of the new and improved Soderbergh. Obviously, there’s the epilogue where Soderbergh talks about how good The Limey is going to be, and how Jersey Films has offered him a job to direct something called Erin Brockovich, but an entire day in the diaries is devoted to Soderbergh talking about his feelings towards the legalization of drugs (gee, I wonder if he ever put that to use). It’s like in every famous person biopic, when the subject spots something that hints at their future (example: young Steven Spielberg spots a poster advertising a shark hunt, considers it but soon leaves), except this time, Soderbergh had no way of knowing about his future, unless he is a wizard.

But getting back to the topic of Soderbergh’s post-Schizopolis career, he’s struck me as being someone in complete control since his “lost” years. After all, this is the guy who told Warner Bros. to make the Ocean’s sequels, not the other way around. Before Schizopolis, he was a weaker willed filmmaker (he talks in GAWI about how he cut several minutes out of King of the Hill for no real good reason, which he believes hurt the film in the long run), but there is not a film he’s made since which doesn’t scream his name. He’s really the person who knows best where his films need to go, more than the studios (who have completely left him alone to make the projects he wants to make, even Miramax), more than the producers, more than even the writers (sorry Dobbs, The Limey is perfect as is). Even when his movies don’t quite hit the mark (hello Full Frontal), they are his, whoever the writer or the stars. The wide diversity of genres he’s covered would seemingly rule out him being an auteur, but there’s a good link between the approaches for Che and Haywire, The Girlfriend Experience and Magic Mike, Side Effects and Schizopolis, And Everything is Going Fine and Contagion. Reading Getting Away With It is like going back in time and watching your successful friend flail his way back to the top.

wallflower: Soderbergh is an auteur in much the way Sidney Lumet was an auteur; there was a unifying intelligence behind all the work and the practice, but not necessarily something you can define ahead of time. You know it when you see it. Pauline Kael called Lumet a “Method director,” meaning that he tried to put himself in the mentality of the characters and shoot the movie according to that mentality. I think the term also applies because Lumet and Soderbergh both have worked in a really diverse range of genres and styles, and they rarely write their own movies. This makes them different from, say, Woody Allen, P. T. Anderson, or Wes Anderson. With both of them, there’s less of a sense of “how does this director express himself?” but rather “what is the best way to shoot this particular scene?” and because there’s such a deep, personal intelligence at work, it’s going to come out in a distinctly Lumetian or Soderberghian way. You mentioned the scene from Erin Brockovich (that’s the first thing I remember from that movie, too); I’ll mention the great moment in Ocean’s 11, where Reuben decides to join up. Soderbergh just holds the camera in the back and lets Elliott Gould walk into the center of the frame (his Aztec-warrior pool-loungewear is screamingly funny), then moves in slowly while he and Pitt and Clooney talk, then cuts to the two shots of Bernie Mac with Clooney’s voiceover. (The second shot of Mac, happy as a clam in polyester, is another laugh-way-out-loud moment.) It’s both a very funny and very elegant 45 or so seconds of film, which is exactly what Ocean’s 11 should be.

Usually when we talk about auteurship, we talk about it in terms of emotion, psychology, personal history. Soderbergh’s defining characteristic as an auteur is his intelligence, and intelligence can be as unique as emotion. Soderbergh’s thinking is analytical, looking to break films, stories, characters, and scenes down into their component parts and finding the best way to do each. A good point of contrast to Soderbergh would be Werner Herzog, whose intelligence is more exploratory and intuitive than Soderbergh’s. Herzog keeps seeking out newer and stranger things, and trusting his instinct to film them. You are probably not going to see anything like the Iguanacam sequences from Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans in a Soderbergh film, but you also won’t see the incredibly boring procedural stuff. Herzog clearly didn’t care about that aspect of the film, and Soderbergh cares about everything.

Because Soderbergh’s intelligence is so analytical, he did his best work when he moved away from a personal subject. Schizopolis, as you know, holds second place in my best-of-Soderbergh list, behind Che. Two aspects of the making of Che raised the final product to masterpiece status: first, he deliberately structured the two parts around Che Guevara’s different source texts. The first part was based on Che’s Reminiscences of the Cuban Revolutionary War, the second on The Bolivian Diary, and it’s the first word of the first title and the last word of the second that count. Soderbergh made part one very stately and classical with a clear direction to the action, shot in 2.35:1 with a lot of formal compositions and vistas; part two is jittery, messy, unclear of where anything is going except that things are getting worse and worse, shot in 1.78:1 (as you said, even the frame is closing in) with handheld cameras. Part one is How to Make a Revolution; part two is the Passion of Che Guevara. It’s his best film because he’s applying himself to someone else’s vision, and yet he makes something no one else could make. (Style is the stuff you can’t help doing.) It has the same place in his filmography as No Country for Old Men has for the Coens.

The other thing Soderbergh had going for him on Che was a limitation: he said that “it was such a difficult production that whether or not what you got was up to a certain standard was not even in your mind during the day. . . .But to get pushed that hard creatively is a good thing.” The danger of being so analytical an auteur is that one’s films can become sterile, but the challenges (and speed–Soderbergh shot this four-hour-plus movie in 39 days) of making Che forced him to make decisions quickly and work with his intuition. Shooting with the new digital RED camera helped too; Soderbergh has said the greatest advantage of shooting digitally is the ability to immediately look at the footage, recognize problems, realize ideas, and change direction. Related to this, Che was also helped by simply getting Soderbergh out of cities and sets and putting him in forests and mountains (there are some scenes here that rank with Malick and Kurosawa in their sense of people moving through a landscape). Samuel Fuller once said that the only way to make a war movie would be to drop a director and film crew in with a squad, and follow them all the way through a campaign, and Che comes about as close to that as can be done.

The Narrator: As always, incredibly well said. Soderbergh is someone who definitely needs at least some kind of limitations in place to make great art or even commercial entertainment (he talks in the Ocean’s Eleven commentary about how he wanted to shoot it in black-and-white, which the studio would have let him do if he lowered the budget by $85 million). Without some kind of opposition, the results are not as potent as they should be (he talks on the King of the Hill Criterion about how Universal was very hands-off about The Underneath due to the fiasco of Waterworld, and how they could literally not get anyone on the phone). Which is why TV seems like such a natural home for him. The constraints of “you must shoot these amount of pages by this day” would seem to bring creative wonders for Soderbergh, and judging by the premiere of The Knick, the results speak for themselves. At no point in that episode is there a shot that doesn’t need to be there, or something that’s just there because it looked stylish. I can’t wait to see where he goes with the rest of the show, which so far is solidly written but brilliantly directed in an unshowy fashion (if that makes any sense).

In many ways, Soderbergh’s style as a DoP (sorry, I mean Peter Andrews) is the result of economy. The man knows how to light and frame a shot, but it’s not out of “oh boy, this is gonna look great” as opposed to, as you say, “this shot is gonna be the best representation of this scene”. After what he saw as being pointlessly stylistic with The Underneath, he went in seemingly the opposite direction with the rest of his work; style that isn’t invisible, but it’s subtle. You watch a Soderbergh movie, and even if you think a shot looks great, that’s not the first thing on your mind. This is taken to its extreme in Full Frontal, which uses DV to purposely take the audience’s eye off the aesthetics of the film and direct them towards the characters (obviously, that didn’t work for many people), and even the sequences shot on 35mm look just mediocre enough that we can’t be awed for them (on the commentary, Soderbergh talks about how he was going for “really good sitcom lighting” on those sequences). The intelligence you mention manifests itself behind the camera in addition to in front of it.

wallflower: Jean-Luc Godard wonderfully said “great art is algebra and fire.” We members of Western civilization, because of our commitment to values like individuality and freedom, risk overvaluing the “fire” part; we often describe art as if takes nothing more than being an interesting person and expressing that. If that were true, we would rank Tommy Wiseau as a better director than Soderbergh. (Nearly everyone who praises The Room praises it for what it reveals about Wiseau, not for what it is.) Soderbergh has such a love for the “algebra” part of Godard’s description, that is, for the craft of filmmaking. He’s continued to grow in his skill as a filmmaker; as you noted, he continues to investigate and develop styles of presenting scenes that are exactly right for the material at hand. Like a lot of artists who are highly skilled in craft, the more he learns, the simpler he gets. One specific thing to look for is that Soderbergh consistently has the best opening shots. A repeated Soderbergh tactic to start: sound over blackness, then cut to image, often a face, often with a time-stamp. The sequence is sound, then setting, then character. The most effective use so far was in Contagion.

Looked at this way, Schizopolis can be seen as a huge, necessary, and brilliant indulgence on Soderbergh’s part. It was a way of clearing himself by taking a bunch of things that had been bouncing around in his mind, including jokes, shots, and the turmoil of his divorce, and just throwing it all onscreen. (Come to think of it, Schizopolis really is Soderbergh’s The Room.) Once he did that, for the next decade-plus, he did a great range of projects, each one of which put him under a series of constraints: the adaptation and multiple narratives of Traffic, the big-budget star-laden entertainments of the Ocean’s films, genre pictures like Haywire and Contagion, the nonprofessional cast of Bubble, and oh so many others. Each one of which gave him a set of problems for his unique intelligence to solve–for example, in Bubble, he notes that one thing nonprofessional actors aren’t good at hitting marks, so he had to film it in a looser style. The Ocean’s movies are genre movies, but made with a commitment that he couldn’t find in The Underneath. In that way, he’s as personal a filmmaker as David Lynch or Terrence Malick, but the personal characteristic is the diversity of what he can do rather than a unifying theme or style. Almost always when I describe Soderbergh to someone, I don’t mention a typical Soderbergh film (there’s no such thing), but the 2000-2002 run: Erin Brockovich, Traffic, Ocean’s 11, Full Frontal, and Solaris. (On the Lester Scale from Getting Away with It, that’s one Masterpiece, two Classics, one worthwhile divertissement, and one Really Fascinating Film That Gets Better with Age.) That’s the director he is–he did those five films wildly diverse films in three years. We don’t apply the label “auteur” who does that kind of thing, but there’s no one else around who could have done it.