(Contains some textual spoilers for The Farewell and a video essay full of spoilers from the movie.)

The first time I assembled a mix of original songs or instrumentals from the movies that were gifted in a Solute movie gift exchange, all the titles that were represented in the mix were movies I saw. That isn’t the case with the 77-minute “This Will Clear Out All the Bad Toxins: The Solute July 2021 Movie Gift Exchange Soundtrack Mix,” the second in a series of Solute mixes I posted on my HearThis account. I’ve seen only six of the 13 movies that are represented in “This Will Clear Out All the Bad Toxins.”

The two movies I was happiest to see gifted in the July 2021 gift exchange were Star Trek: The Motion Picture and The Farewell.

The Ploughman adores TMP, the first Star Trek movie and the only one where Trek creator Gene Roddenberry had creative control. Sure, it’s the only Trek movie where the protagonists are actually trekking and exploring like the heroes on most of the pre-2017 Trek shows—I say “most” because Star Trek: Deep Space Nine had little to do with exploration and was more about rebuilding a war-torn society and dealing with the threat of another war, and Star Trek: Enterprise turned into “24 in Space” in its third season—instead of battling a supervillain or getting into comedic trouble in Earth’s distant past. But my feelings about TMP are mixed. I liked it better when it was called “The Changeling.”

The two younger characters who were carryovers from the movie’s roots as a TV reboot pilot script are flatly written, and their bland love story—a reunion between a captain we never met before and his old flame, a native of the sexually advanced, previously unmentioned planet Delta IV—takes away too much screen time from Kirk, Spock, Dr. McCoy, Scotty, Uhura, Sulu, Chekov, and Dr. Chapel. I don’t need this much Stephen Collins in my life. It’s a good thing the disgraced pedophile’s appearances as Dennis and Dee’s biological dad were kept to a minimum. Collins and Persis Khambatta have zero chemistry. It must have been because he considered her to be too old for him.

The idea of a sexually advanced alien woman whose pheromones turn her human male crewmates into the Tex Avery wolf—as seen in a comedic scene between her and a googly-eyed Sulu that’s only in ABC and Paramount Home Video’s 1983 “Special Longer Version” of TMP—is the most Dirty Old Man Roddenberry thing about this movie that was produced by the famously lecherous writer of both the kinky-for-its-time “The Cage,” the first Trek story ever, and the 1971 Roger Vadim flick Pretty Maids All in a Row, which is basically Wild Things if it had been written in 1970 by an over-the-hill male swinger who didn’t know lesbians exist. How come some of the other women in TMP don’t get to fall under her spell too?

All the stuff about Delta IV and Ilia, the new Enterprise’s Deltan navigator, is badly in need of a woman’s touch. That would have been a good time to summon Dorothy “D.C.” Fontana—one of the first female writers to break the glass ceiling in Hollywood when she moved on from secretarial work to writing episodes of the early ’60s NBC western The Tall Man and the original Trek—back to the Trek franchise.

TMP has some of the worst ADR I’ve ever heard in a Hollywood blockbuster. The 16mm rear projectors the filmmakers went with to display the graphics on the station monitors on the set of the revamped Enterprise bridge were so noisy that the cast had to redub most of the dialogue in the bridge scenes. The ADR is most noticeable in the awkward reunion scene between Spock, who recently purged himself of his emotions due to a Vulcan emotion removal ritual, and his old crewmates, who are like, “What the fuck, Spock? That semester in Paris has made you a dick, man.”

When David Wain’s hilarious They Came Together makes fun of lousy ADR during its basketball court scene, the ADR during Spock’s awkward return to his old science officer station on the bridge is the first thing that comes to my mind. The TMP cast members weren’t exactly great at ADR, even though many of them had some prior experience doing somewhat similar voice work for Filmation’s animated revival of Trek five years before they filmed TMP. It’s as if they were voice-directed by the uncredited American guy who redubbed the Italian actor who played the John Cassavetes character’s son in Machine Gun McCain. According to The Narrator, the unknown Machine Gun McCain dubber “gives one of the worst vocal performances I’ve ever heard in a movie.”

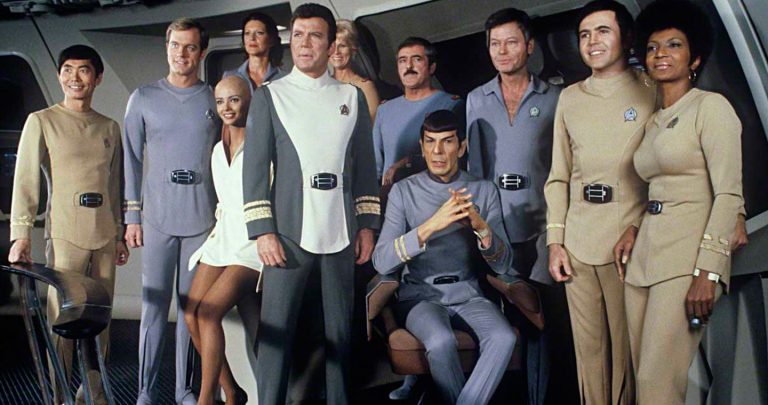

The stiffness and ’60s Bible film-like solemnity of TMP aren’t helped by beige, brown, white, and blue-gray uniforms that make all the Starfleet officers in the movie look like they’re going to beam down to Kid ’n Play’s Pajama Jammy Jam fundraiser for Kid’s college tuition in House Party 2. Over at Accidental Star Trek Cosplay, I often refer to TMP as Star Trek: The Pajama Jammy Jam. The late costume designer Robert Fletcher bears the distinction of creating both the ugliest Starfleet uniforms in the history of Trek—beige uniforms and the Trek franchise go together like Poochie and The Itchy & Scratchy Show—and the best-looking ones, which were the double-breasted “Monster Maroons” Fletcher introduced in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan.

The Pajama Jammy Jam is weirdly ashamed of the great Gene L. Coon era of ’60s Trek—in a non-fiction book I’m currently working on about the Filmation Trek, Star Trek: Lower Decks, and Star Trek: Prodigy, I explain why I don’t like using the retronym of TOS to refer to the original series, and the short version of my long explanation is that the acronym always makes me think “Terms of Service”—as well as many of D.C. Fontana’s equally valuable contributions to both ’60s Trek and the Filmation version, which she showran in Season 1. As writers, both Coon, who showran Season 1 and most of Season 2 of ’60s Trek, and Fontana ran rings around Roddenberry, who had a contentious working relationship with Coon.

Roddenberry wanted his protagonists, except irascible McCoy, to be completely humorless, which is what they are in TMP, except, of course, McCoy. (“Yeah, the thing I know about Gene Roddenberry is that he had no sense of humor. He didn’t understand jokes. It was not that he was a grim man… I think Gene’s military training kind of beat his sense of humor out him,” recalled “The Trouble with Tribbles” episode writer David Gerrold to TrekMovie in 2014.) Coon preferred the protagonists to be more relatable and capable of cracking jokes—including Spock, who occasionally comes up with dry insults directed at McCoy even though, as the doctor points out in the Fontana-scripted Filmation episode “Yesteryear,” Vulcans don’t tell jokes. When Coon and his short-lived replacement in the showrunner position, “The Changeling” episode writer John Meredyth Lucas, left ’60s Trek, the humor left with them, and the show’s quality started to sink like a hastily glued toupee atop William Shatner’s head.

However, one of the worst things about the Coon era—the “Please Laugh Now” score music that always accompanied the show’s comic relief moments because it was still the age of canned laughter on sitcoms, and network TV required canned laughter or, for shows that weren’t sitcoms, “Please Laugh Now” cues to tell audiences where the jokes were—is wisely absent from TMP’s three or four comedic moments. This is also why Lower Decks is better at humor than the comedy episodes that were occasionally done by Coon-era ’60s Trek and Star Trek: The Next Generation: Lower Decks composer Chris Westlake avoids writing “Please Laugh Now” cues and scores Lower Decks as if it’s a drama.

“There are jokes in the situations the characters are in, but the music has to think it’s in a [Star Trek] movie or one of the TV shows,” said Westlake to Syfy Wire in 2020. “It has to be sincere and not too aware of itself. And the more seriously we took the music, the funnier the comedy became.”

TMP wasn’t the Trek movie that got me hooked on the franchise. Instead, it was the subsequent “Monster Maroon” era of Trek that did it for me—particularly the Genesis Trilogy, which I enjoyed long before I first watched TMP on ABC in 1989, and the DC Comics Trek series that ran from 1984 to 1988 and added to the movie-era Enterprise crew a Klingon named Konom, who was like a precursor to Teal’c, the Jaffa defector on Stargate SG-1. Konom became the first of his people to join Starfleet. This was before Worf became the canonical first Klingon in Starfleet on TNG and remained the only Klingon in the fleet when Michael Dorn’s enjoyably grumpy character was added to the cast of Deep Space Nine, my favorite out of all the Trek shows so far, with Lower Decks—the first Trek show with a Filipino American Starfleet officer as a main character (engineer Samanthan Rutherford, excellently voiced by Eugene Cordero)—a close second.

The only Trek movie directed by Hollywood journeyman Robert Wise is a flawed and imperfect epic, and though a lot of things in TMP bug me—particularly a wormhole distortion sequence that’s as exciting as a tax audit—TMP has a few terrific moments. On the very funny The Greatest Generation and the equally funny Greatest Trek, my two favorite Trek episode discussion podcasts in a podcastosphere that has way too many Trek episode discussion podcasts, hosts Benjamin Ahr Harrison and Adam Pranica refer to a favorite character of theirs who doesn’t give a fuck as the “Drunk Shimoda” of the episode. It’s in honor of Jim Shimoda, a never-seen-again Enterprise-D engineer character who drunkenly builds for fun a Jenga tower out of the warp drive’s isolinear chips in the crappy 1987 TNG space virus episode “The Naked Now.” My favorite Drunk Shimoda in TMP is a silent and faceless drydock worker in an EV suit who’s so excited about the new Enterprise that they do a backflip and wave goodbye to the ship as it leaves drydock. That drydock worker has to be either a descendant of one of the Jabbawockeez or an ancestor to Lieutenant Commander Billups, the Cerritos chief engineer who cries tears of joy while admiring his ship during Lower Decks’s hilarious parody of the divisive TMP sequence in which Kirk lovingly gazes at the Enterprise from his travel pod for six uninterrupted minutes.

Best of all, the score Jerry Goldsmith composed for TMP is phenomenal from overture to finish, even though he omitted the eight-note Alexander Courage brass fanfare that was part of every episode of ’60s Trek. (All 12 subsequent Trek movies included the classic fanfare.) The score makes beautiful use of the weird instrument known as the blaster beam, an 18-foot-long metal beam that creates ominous gong noises when it’s struck. The instrument represents V’Ger, a being of unknown origin the Enterprise crew must reason with to stop it from wiping out every living thing on Earth. The blaster beam is a highlight of this score, James Horner’s Star Trek II score, and Quincy Jones’s catchy 1981 cover of “Ai No Corrida,” Chaz Jankel’s 1980 blue-eyed R&B track about the kinky couple from In the Realm of the Senses. Musician Craig Huxley, a former child actor who appeared twice on ’60s Trek, played the blaster beam during “Ai No Corrida” and all of the Trek franchise’s uses of the instrument, from the TMP score to composer Stephen Barton’s scores for Star Trek: Picard’s current and final season.

One of my favorite headphone experiences was revisiting Goldsmith’s score while watching for the first time the best version of the movie: the 2022 4K restoration of the director’s cut Wise oversaw in the early 2000s because he was never satisfied with the theatrical cut—the result of a famously troubled shoot that had to be rushed to get TMP into theaters for Christmas 1979—and he wished he could go back, tighten up the pace of the movie, and redo a few visuals that looked inelegant to him or were simply unfinished, whether it was the lifeless, Woody Allen-esque way the opening credits and the closing tagline materialized or the climactic walkway V’Ger built between its nucleus and the Enterprise saucer section. Like Sledge Hammer! creator and ’60s Trek fan Alan Spencer once quipped on Twitter, if you’re a Goldsmith fan, TMP is “a great concert film.” Otherwise, it’s a movie that doesn’t quite come together.

Star Trek: Discovery’s fourth and penultimate season is a better version of what TMP was striving for as cerebral, 2001: A Space Odyssey-style sci-fi that was devoid of a supervillain—TMP and Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home are the only Trek movies without a supervillain—and a lot of pew-pew-pew. It sometimes pays visual homage to TMP’s epic depiction of the enormity of space and centers on a first-contact mission to reason with an incomprehensible alien species that, just like V’Ger, doesn’t understand the destruction it’s leaving in its wake. TMP is weirdly uninvolving—except for one key character’s arc, which I’ll get to in a few moments—whereas Discovery Season 4 is definitely involving, particularly in the arc where Book, who loses his brother, his nephew, and his homeworld to a destructive anomaly created by Species 10-C, becomes torn between sticking to the non-violent diplomacy preferred by Captain Burnham, his girlfriend, and disobeying her to get revenge against Species 10-C. Season 4 also has a bit more humor—often in the form of the great Tig Notaro as deadpan engineer Jett Reno.

Meanwhile, The Farewell is perfect. It’s the first of three excellent A24 releases about the East Asian American experience in the last four years, and it was followed by director Lee Isaac Chung’s Minari in 2020 and Everything Everywhere All at Once, the Daniels’ recent multiple-Oscar winner. Like two other gift exchange entries that are represented in “This Will Clear Out All the Bad Toxins,” The Dressmaker (which I haven’t seen) and The Secret of Roan Inish (which I watched for the first time immediately before producing the mix), The Farewell centers on a female character who reconnects with a place she left behind.

Even though I’m Filipino American and not Chinese American—we Filipinos are Southeast Asians, and Southeast Asian cultures are different from East Asian ones—The Farewell’s story of the bond between Awkwafina’s Chinese American writer character and her terminal grandmother in Changchun connected with me in ways that were absent from my experience with Awkwafina’s earlier movie, the screen version of Crazy Rich Asians, which was colorist against brown Asians and is already not aging well. I wasn’t close with my maternal grandfather—a tailor who was the only grandparent of mine I remember meeting—like Billi, Awkwafina’s character, is with her grandma, but The Farewell made me think fondly of the first and last time I got to know him when I once visited my parents’ homeland of the Philippines when I was a teen.

I love the story about how Lulu Wang, The Farewell’s writer/director, fought to tell The Farewell her way.

“When heading in to pitch meetings with potential producers or financiers, [Wang] came armed with a list of non-negotiables. ‘Let me just tell you straight up that it is going to be Chinese-language, it’s going to be cast entirely Asian and Asian American, and she will not have a white boyfriend,’ she recounts of her conversations with executives,” wrote Mia Galuppo in a 2020 Hollywood Reporter profile of Wang.

American producers wanted Wang to turn the movie’s story, which she based on experiences she discussed in an investigative journalism-style This American Life essay in 2016, into a broad comedy in the vein of My Big Fat Greek Wedding.

“Many [American financiers] suggested that Wang introduce a prominent white character into the narrative… But Wang felt her story didn’t need the token white character; it already had Billie [sic], the young protagonist, whose experience in a large immigrant family was specific to the Asian American experience,” wrote Eric Kohn in a 2019 IndieWire interview with Wang.

In China, executives over there couldn’t understand why the lead character Wang based on herself was so conflicted, and they requested that she make Billi less conflicted and Westernized.

“Both sides were looking at it in a binary way, where it’s east versus west,” said Wang to the Guardian in 2019. “Versus, as opposed to finding the bridge between the two, or the space in between to be able to navigate both.”

The Farewell is often funny, but it’s not a broad comedy—thank fuck—and Wang’s interest in that space where her lead character discovers how to navigate both cultures makes the movie unique.

TMP and The Farewell dominate “This Will Clear Out All the Bad Toxins.” The tai chi scene from the latter is the source of the mix’s title. The audio from that pivotal scene—Nai Nai (beautifully played by Zhao Shuzhen) teaches Billi how to do breathing exercises to release negative energy, and she doesn’t know that she’s passing on to Billi an effective way to overcome her sorrow over someday losing Nai Nai—is part of the mix, and because the dialogue is entirely in Mandarin, I’ll translate the audio right now.

“Come do it with me! Hah! Ho! Hah! Hah!” says Nai Nai to Billi.

“Hah. Hah,” says Billi.

“Aiyah! Be serious. Try harder. This will clear out all the bad toxins. Hah! Hah! Then you inhale to take in fresh oxygen. Understand?”

“Yes.”

“Let’s do it together. Inhale. Hah! Hah!”

“Hah. Hah.”

“Make it stronger. Open your eyes! Lift your chest!”

“OK, got it.”

“Do you get it?”

“I get it.”

“You can also slap your arms. Ah. Slap your back.”

“Slap my butt?”

“Ha ha ha ha ha!”

I sometimes like to slip into my HearThis or Mixcloud mixes a hidden track as an Easter egg after 15 or 20 seconds of dead air at the end. I did that at the end of “This Will Clear Out All the Bad Toxins,” and the hidden track is another scene in Mandarin from The Farewell, so I’ll translate the audio from that scene too.

“Hey,” says Nai Nai to all her relatives at a family portrait session.

“Hey, everyone say, ‘Eggplant!’ One, two, three!” says the photographer.

“Eggplant!”

The score to The Farewell, composed by Alex Weston, a former assistant to Philip Glass, may not be seminal or hummable like Goldsmith’s TMP score, but it’s equally impressive. The Farewell hinges on a culture clash between Billi, an only child, and her extended family. Nai Nai is dying of lung cancer, and Billi’s parents and relatives have chosen to do what many other families in China have done for terminal loved ones by hiding her terminal diagnosis from her so that she can enjoy her last few months without any stress or sadness. (“Chinese people have a saying: ‘When people get cancer, they die. It’s not the cancer that kills them. It’s the fear,’ ” says Jian, Billi’s mom and Nai Nai’s daughter-in-law, to Billi.) Nai Nai’s sister and children will stage a wedding between Hao Hao, Billi’s cousin from Japan, and his new girlfriend Aiko as a way for the family to bid farewell to Nai Nai. But Billi—who grew up in America, where withholding from a patient information about their condition is considered unethical and illegal—doesn’t agree with lying to her favorite family member and wants to expose the truth to her.

Neither side is wrong in this ethical dilemma. But all of Nai Nai’s loved ones—whether it’s Billi or her Uncle Haibin, who chides Billi for being too influenced by American individualism and failing to understand Chinese collectivism—agree on one thing: A woman so full of life and compassion will be gone soon, and it fucking sucks. In “This Will Clear Out All the Bad Toxins,” you get to hear how Weston’s minimalist score, his wordless falsetto vocalists—including Mykal Kilgore, whom I had no idea is male until Weston pointed it out in a radio interview—and Elayna Boynton, the singer of Weston’s cover of the 2012 Leonard Cohen song “Come Healing,” effectively express the grief Jian, Hao Hao, Aiko, Uncle Haibin, and, in a surprising turn of events, Billi can’t express in front of Nai Nai because it would give away the lie. The score and the vocalists carry the characters’ emotional burden in the same way Nai Nai’s loved ones carry the emotional burden for her.

However, in one of The Farewell’s many unexpected moments of humor, Hao Hao and Aiko are so saddened by Nai Nai’s condition that they can’t convincingly play the roles of happy newlyweds at their fake wedding, and their visible misery keeps threatening to give away the lie. Nai Nai complains to Billi about the bride’s lack of enthusiasm and mistakenly thinks the couple’s misery is because Aiko is frigid in bed.

Weston’s musical minimalism suits The Farewell, its small and intimate story, and its theme of dealing with repressed emotions, while Goldsmith’s TMP score, particularly the optimistic main title march, needed to sound grand—or else Wise’s mostly lethargic epic would have crashed and burned like a SpaceX rocket without that type of score.

I never liked Rick Berman-era Trek composer Dennis McCarthy’s arrangement of Goldsmith’s TMP main title march for TNG’s opening titles. The McCarthy version was performed by a 38-piece orchestra. Goldsmith’s TMP march is the type of instrumental that sucks when it’s not performed by a 98-piece orchestra, which was how big Goldsmith’s orchestra was in TMP. The trumpet solos during the TMP version of the march and “The Enterprise,” the cue from the six-minute travel pod sequence, have a wonderful, Doc Severinsen-ish jazzy sound, even though Doc wasn’t one of Goldsmith’s trumpeters. Whenever I hear those solos, I keep picturing Doc going to town on his trumpet in a blazer that looks like a LeRoy Neiman sports painting exploded on his chest. Or I’m picturing Herb Alpert with his trumpet just like in his 1982 “Route 101” music video, except he’s swaying back and forth in Scotty’s engine room. The McCarthy version doesn’t have that sound.

I don’t care that TNG had to adhere to a weekly TV budget. Sci-fi or action show scores don’t have to sound so small and tinny. Bear McCreary managed to get a 65-piece orchestra when he scored the first and best season of Human Target, and that season and its main title march sounded amazing.

Although the McCarthy version is underwhelming, the TNG opening titles deserve credit for going with a majestic Goldsmith movie theme as an opening title theme to a TV show instead of going with a composition like the rejected, The Adventures of Superboy-esque theme McCarthy first wrote for the titles, which is even more underwhelming than his arrangement of the march. The titles introduced the march to generations of viewers who never watched both TMP and Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, where Goldsmith brought the march back to the movie series after he sat out the series for 10 years, so they associate the march with Picard and the Enterprise-D crew instead of Kirk and Spock. It’s now so synonymous with Picard that composer Jeff Russo briefly quoted it at the end of his Picard Season 1 main title theme, and the Picard Season 3 main-on-end title sequence currently brings back the big-screen version of the march in all its glory, although it’s, of course, Goldsmith’s Star Trek: First Contact arrangement of the march, which I also love, instead of his arrangement from TMP.

“I guess what I tried to end up saying with this theme was that these people are adventurers and explorers and they’re going out in this uncharted territory—it’s no different than what you’d play in Roman times as the legions go out or the stirring music you’d play in a western as they’re going across the plains,” said Goldsmith about the march to an interviewer at around the time Wise’s director’s cut debuted on DVD in 2001.

This theme that perfectly expresses the wonders of adventuring into uncharted territory is included in “This Will Clear Out All the Bad Toxins,” but I went with the travel pod sequence version and the end title version because whether you hate the travel pod sequence or not, Goldsmith’s music in that sequence is so terrific it’s inspiring even without the visuals, and the transition from “Ilia’s Theme” to the march in the end titles never fails to make me think, “Damn, Goldsmith was the illest!” The transition is as cool as noted Trek fan Pharrell Williams’s signature four-count start.

TMP and The Farewell may not have a lot in common—TMP was one of several big-budget ’70s attempts by 20th Century Fox’s rivals to compete with the then-Fox cash cow Star Wars, while The Farewell is an A24-distributed indie—but one big thing ties the movies together and makes The Farewell both an unlikely companion piece to TMP and a perfect neighbor to the 1979 movie in “This Will Clear Out All the Bad Toxins.” Billi struggles to navigate two worlds: American culture, where she feels more at ease, and her Chinese heritage, which she left behind when her immigrant parents brought her to America when she was little.

“I think people have this romanticism of the homeland, and that’s just not the reality for me,” said Wang to the Guardian. “Every time I go back to China, I feel more American than ever, so it’s this question of, ‘Well, where is home?’ We’re always searching for it and never fully fitting in.”

Despite her distance from China and her struggles to hold onto her knowledge of Mandarin, Billi has been able to stay in touch with her heritage through her close relationship with Nai Nai. During her trip to Changchun to see Nai Nai one last time, Billi reconnects with the happy times she had with both of her grandparents before she moved to America while also grappling with the fear that the loss of Nai Nai could also be the loss of her only link to her heritage. Her dual identity is similar to the dual identity of Spock, whose primary internal conflict throughout the ’60s show’s run dealt with his desire to fully embrace the logic-based culture Vulcans like himself and Ambassador Sarek, his full-blooded Vulcan father, were raised in, but all those pesky emotions that fuel humans like his mother Amanda Grayson, his ex-girlfriend Leila Kalomi, his best friend Kirk, and nearly everybody else on the Enterprise kept getting in the way.

Spock’s lonely existence of being caught between two worlds makes him the most compelling character from ’60s Trek, particularly to neurodivergent folks, LGBTQ Trek fans, mixed-race viewers, and children of immigrants who relate to Spock’s dual heritage. When Leonard Nimoy passed away in 2015, the bloggers over at the now-defunct, Justin Lin-founded Asian American blog You Offend Me You Offend My Family, a.k.a. YOMYOMF (pronounced “yawm-yawm-eff”), discussed why they loved Nimoy and Spock in a post that’s no longer online.

“I know Sulu was the Asian on Star Trek, but I would consider Spock an honorary Asian on the show because he was the strange-looking, [sic] intellectual who wasn’t emotional. I always thought he was a lot cooler than Captain Kirk. Plus that Vulcan Death Grip? We kids were always re-enacting that,” wrote YOMYOMF co-blogger Iris Yamashita, who also wrote the screenplay for Letters from Iwo Jima.

“Much like Iris, I always thought that Spock was Asian. He just looked more Asian than not. So as a child, I just assumed he was Asian,” added actor and YOMYOMF co-blogger Roger Fan, a Lin movie regular who was effective as the sociopathic Daric in Better Luck Tomorrow (which Joseph Finn gifted to The Psychic Johnny Smith in the July 2022 Solute gift exchange) and funny as Breeze Loo, an egocentric Bruce Lee wannabe, in the 2007 Lin mockumentary Finishing the Game.

TMP may be a mixed bag as a Trek movie, but it sparks to life whenever the focus is on Spock’s internal conflict. His first scene takes place on Vulcan, where his final stage in the aforementioned emotion removal ritual—Vulcans call the ritual the Kolinahr—is interrupted by an alert from his Spider-Sense, which tingles because of the V’Ger crisis. Friendly Neighborhood Mr. Spock is so concerned about V’Ger’s path of destruction that he cuts short his Kolinahr and chooses to return to Starfleet to help out his old friends on the Enterprise in protecting Earth from the alien entity. The leader of the Vulcan masters, who reminds me a lot of the judgy and smug relative who pisses off Jian because she shames her and her husband for leaving behind Nai Nai and immigrating to America during The Farewell’s Lazy Susan dinner scene, gives Spock a zero on his Kolinahr and shames him for being half-human.

Later on in the movie, a Vulcan mind meld Spock performs with V’Ger to investigate its true purpose nearly kills the Enterprise science officer. It also forever changes his life, but you wouldn’t know that it does from TMP’s theatrical cut, which omits a crucial scene on the bridge after he recovers in sickbay.

On his sickbay bed, a dazed Spock laughs, holds Kirk’s hand in a moment that caused the hearts of ’70s women who wrote Kirk/Spock slash fanfics to flutter, and tells Kirk that elements that are crucial to humans like emotions or holding the hand of a person you love are beyond the comprehension of V’Ger, a sentient machine that’s beginning to wonder about its purpose in life. In the theatrical cut, Spock’s discussion of his mind meld with V’Ger ends right there.

But in the 1983 “Special Longer Version,” the 2001 director’s cut, and the 2022 redo of the director’s cut, Spock’s contemplation of what he gleaned from the mind meld continues. Mr. Majestyk cinematographer Richard H. Kline’s camera does a slow pan across the bridge as each bridge officer updates Kirk on the V’Ger crisis. Then Kline gets to Spock, whose back is turned to the camera. Spock is so lost in his thoughts that he doesn’t respond at first when Kirk asks him for a report. When he finally turns around and faces Kirk, a single Denzel Washington Glory tear rolls down his face.

Spock was previously seen crying in “The Naked Time” and “The Devil in the Dark.” In the former, his crying jag was due to getting drunk from a space virus that turns everybody into either John Boehner or “Flaming Moe’s”-mode Ms. Krabappel, while in the latter, he wept while in a mind meld with a Horta creature because he was experiencing her grief over the losses of her children, who were killed by miners who weren’t aware that the silicon spheres they were accumulating were her eggs. But in TMP, he’s not choking up because he’s under the influence of a virus or an alien. He’s feeling genuine sorrow for both V’Ger, whose quest for its purpose and its creator mirrors his unfinished Kolinahr, and himself because his Kolinahr has left him feeling empty instead of fulfilled.

“I weep for V’Ger as I would for a brother. As I was when I came aboard, so is V’Ger now—empty, incomplete, and searching. Logic and knowledge are not enough,” says Spock to Kirk and McCoy. “Each of us, at some time in our life, turns to someone—a father, a brother, a god—and asks, ‘Why am I here? What was I meant to be?’ ”

You may be most fond of the six-minute travel pod trip to the Enterprise, the comedic “Disco McCoy” scene, the drydock departure sequence that left many 1979 Trekkies in tears, or Persis Khambatta’s “Nair for short shorts” commercial legs, but without that scene where Spock confesses that V’Ger’s existential crisis has deeply affected him, TMP is trash. Because I’ve seen only the sloppy 1983 ABC cut and the much more elegantly edited director’s cut, I don’t know how this movie can exist without the “Logic and knowledge are not enough” scene. Spock’s startling admission, which was one of Nimoy’s ideas of trying to insert more character moments into a frequently rewritten script he found to be anemic, is the most compelling scene in TMP. It powerfully brings closure to an internal conflict that, on screen, lasted 13 years.

In an archival interview Adam Nimoy included in his 2016 documentary For the Love of Spock, a very good doc about his father even though there are way too many clips from the racist and hacky The Big Bang Theory for my liking, the late Nimoy recalled how Trek’s first opportunity to receive a massive budget from Paramount after previously looking cheap on the small screen meant that TMP “was all about the ship, the ship, the ship. And this effect and that effect. And we’re going through this thing. And now we’re going through that thing. Nothing about the characters. So it was frustrating and depressing and very painful.”

Though Nimoy wasn’t pleased with TMP, he subtly carried over his character’s TMP epiphany that emotions can co-exist with logic into his performance as Captain Spock in Star Trek II. The new Spock, who’s leading a crew of cadets for a training mission on the Enterprise, doesn’t smile or laugh—just like the Spock ’60s and ’70s viewers got to know on TV—but he’s more relaxed, warm, and compassionate. When Midshipman First Class Peter Preston, Scotty’s nephew, is badly burned due to Khan’s attacks on the Enterprise, Spock mournfully reacts to Preston’s condition and closes his eyes in sorrow. The younger Spock would have been embarrassed about reacting like that on the ’60s show. And that’s the biggest reason why Spock’s sacrifice at the end of Star Trek II is so tragic: He didn’t have more time to appreciate his post-V’Ger state of accepting his emotions and seeing them as strengths instead of weaknesses.

Spock’s “Logic and knowledge are not enough” scene is also why I don’t like the title card that pops up before TMP’s end credits: “The human adventure is just beginning.” It’s clearly a five-second diss track aimed at Star Wars—“That movie with the droids and the giant dog-man is for kids who eat their poop; our heroes’ adventures are about the human condition”—but it conflicts with the whole point of Spock’s confession scene. He didn’t say, “Fuck this Vulcan shit. From now on, I’m gonna live my life as a human. This feisty little V’Ger taught me that if it feels good, do it. Be like boy.” He realized that both his human and Vulcan halves have value, and his life will be empty if he chooses to be human or Vulcan instead of both at the same time.

“The human adventure is just beginning” was clearly an attempt to start a new “May the Force be with you”-type catchphrase, but it never caught on like “To boldly go…” did or “Make it so” will later do in the early ’90s. Other than Star Trek III: The Search for Spock concluding with the caption “…and the adventure continues…” to connect itself to TMP, the movie series never references the tagline again.

Also, as a person of color, “The human adventure is just beginning” just sounds to me like “The white man adventure is just beginning.” One of the things that makes Trek special as a sci-fi franchise is that it evolves—just like V’Ger and Spock. It’s the opposite of Law & Order, a crime drama franchise that’s now more conservative and pro-police than it was in 1993. (L&O deserves all the brickbats John Oliver hurled at it in his excellent 2022 Last Week Tonight indictment of its present-day glorification of the NYPD.) Growing out of old ways is something that’s beyond the comprehension of conservatives who claim to be Trek fans but are racist and homophobic as hell about present-day Trek and want the franchise to stay frozen in 1989, a time when it was extremely white and heteronormative on screen and behind the scenes. TMP’s tagline looks silly now because, instead of always making humans the center of everything, Trek went in a more inclusive direction during TNG’s Michael Piller/Ronald D. Moore era and DS9, whose mostly alien cast was a precursor to the completely non-human crew of the U.S.S. Protostar in Prodigy’s first season. Trek isn’t strictly about human or half-human adventures anymore. It’s also about a Klingon who over-romanticizes a culture he wasn’t raised in and ends up becoming a better Klingon than the Klingons he idolized when he realizes that their culture is imperfect. Or a selfish Ferengi bar owner who’s been holding back his brother and his nephew and realizes that he should let them pursue their dreams. Or an Orion lower decker who’s trying to defy hypersexualized and subservient stereotypes of Orion women by becoming a Starfleet captain. Or a nonbinary Medusan fugitive in a containment suit who’s trying to atone for their past as a prison torturer. I adore Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country for mocking a line like “The human adventure is just beginning” in the scene where Kirk says to Spock, “Everybody’s human,” and the latter replies, “I find that remark insulting.”

Spock’s Glory tear scene is as cathartic as the final scene in The Farewell. Billi no longer has any reservations about the lie—exposing the truth could have damaged her relationship with Nai Nai—and returns to her home turf of New York a different person. Like Spock, she no longer feels the burden of navigating two different cultures. Nai Nai’s words of encouragement in Mandarin to not care what anybody thinks of her and to view her dual identity as a beautiful thing instead of a burden have empowered her. She remembers the breathing exercises Nai Nai taught her and lets out in the middle of a New York sidewalk a full-throated “Hah!” instead of the meek “Hah!” we previously saw her do in front of Nai Nai.

When I first saw the final scene back in 2019, I wasn’t moved. But when I saw it again at the end of the Quality Culture YouTube channel’s 2021 video essay “Saying Goodbye to Your Roots in The Farewell”—the best YouTube essay I’ve seen about The Farewell from its first scene to its last moment, a title card that reveals that six years after the diagnosis, Nai Nai is both still alive and still in the dark about her cancer—the ending in New York got to me, and it’s because of how beautifully Terrence, one of Quality Culture’s two essayists, detailed why The Farewell’s depiction of both the complicated grief of feeling lost between cultures and what it means to be Asian American affected him as a Vietnamese American viewer.

“Thousands of miles away, [Billi] comes to a realization: Your family, your culture, and your heritage are always a part of you. And as Billi releases the grief weighing her down, she’s able to let go of the anxiety of losing herself and the understanding that these pieces of her life will always be with her,” says Terrence about the final scene at the end of the above essay.

In fact, Quality Culture’s essay—which also nicely slams the dumb misconception of The Farewell as a foreign film, an example of the ongoing othering of us Asian Americans—helped me out of a writer’s block I briefly experienced while I worked on the above paragraphs about why The Farewell is a good companion piece to TMP. If you haven’t seen either of the two movies in a while, it’d be great if “This Will Clear Out All the Bad Toxins” or this companion article gets you to revisit either of them and maybe watch that movie in a new light. If it’s TMP, make sure you get access to the 2022 restoration of the director’s cut, not the inferior theatrical cut Paramount pointlessly reissued physically and digitally a few times in between 2001 and 2022. Even that title card I don’t like looks nicer now.

“This Will Clear Out All the Bad Toxins” tracklist

- Jerry Goldsmith, “Overture” (from Star Trek: The Motion Picture)

[Clip of Zhao Shuzhen and Awkwafina from The Farewell] - Alex Weston featuring Mykal Kilgore, “Grandma on the Roof” (from The Farewell)

[Jiang Yongbo (in Mandarin) from The Farewell: “You think one’s life belongs to oneself. But that’s the difference between the East and the West. [Sighs in frustration.] In the East, a person’s life is part of a whole. Family. Society.”] - Alex Weston, “Family” (from The Farewell)

[Ewan McGregor: “Everyone’s into the scene because it’s supposedly the thing to do right now. But you just can’t fake being gay. You know, if you’re gonna claim to be gay, you’re gonna have to make love in gay style, and most of these kids just aren’t gonna make it. And that line: ‘Everyone’s bisexual.’ It’s a very popular thing to say right now, but personally, I think it’s meaningless.”] - Shudder to Think, “Ballad of Maxwell Demon” (from Velvet Goldmine)

[Clip of John Cassavetes and a badly redubbed Pierluigi Aprà from Machine Gun McCain] - Ennio Morricone, “Machine Gun McCain (alternate version)”

- Ennio Morricone featuring Jackie Lynton, “La ballata di Hank McCain, Pt. 1” (from Machine Gun McCain)

[Clip of Hugo Weaving and Kate Winslet from The Dressmaker] - David Hirschfelder, “The Dressmaker Opening Titles”

[Clip of James Doohan and William Shatner from Star Trek: The Motion Picture] - Jerry Goldsmith, “The Enterprise” (from Star Trek: The Motion Picture)

- Geeta Dutt, “Jane Kya Tune Kahi” (from Pyaasa)

[John Lynch: “Liam had seen a Selkie, a creature that’s half-human and half-beast. Old stories told of such creatures lurin’ ships onto the rocks and pullin’ sailors down into the drink. But all Liam knew was he’d never seen a woman so lovely in all his life. Now the years passed, and Liam and Nuala, for that’s what the Selkie called herself, was happy in their work, and their love grew, and they had many children. With all that, there was always a touch of sadness about Nuala. And she spent long hours lookin’ out at that she had come from and listenin’ to the cries of the seals on the outer islands. When he got home, it was the faces of his children told him his fears were true. For once a Selkie finds its skin again, neither chains of steel nor chains of love can keep her from the sea. From that day on, it was forbidden to harm a seal on the island. And man and beast lived side by side sharin’ the wealth of the sea. And sometimes the Coneellys would see her, out in the waves, baskin’ in the sun on Skellig, watchin’ them, watchin’ her children.”] - Mason Daring, “The Roan Inish Theme (Radio Edit)” (from The Secret of Roan Inish)

[1974 Mr. Majestyk TV spot] - Charles Bernstein, “Majestyk Main Title” (from Mr. Majestyk)

[Clip of Kurtwood Smith and Kris Kristofferson from Flashpoint] - Tangerine Dream, “Highway Patrol” (from Flashpoint)

[Kevin Bacon: “I tell ya something, man: If I gotta get up in front of that council, then you are gonna learn how to dance.”] - Deniece Williams, “Let’s Hear It for the Boy” (from Footloose)

[Jeanne Moreau: “Oh, je’taime. Oh, je’taime.”] - Miles Davis, “Générique” (from Elevator to the Gallows)

- Miles Davis, “Chez le photographe du motel” (from Elevator to the Gallows)

[Clip of Dan Aykroyd, David Duchovny, and Robert Downey Jr. from Chaplin] - John Barry, “The Cutting Room” (from Chaplin)

[Clip of Robert Downey Jr. and Anthony Hopkins from Chaplin] - John Barry, “Discovering the Tramp/The Wedding Chase” (from Chaplin)

[Clip of Awkwafina and Jim Liu from The Farewell] - Elayna Boynton, “Come Healing” (from The Farewell)

- Alex Weston featuring Amy Marie Stewart, “Pathetique” (from The Farewell)

[Bruce Brown: “The things Wingnut does never cease to amaze me. Here, after getting wiped out, he just bodysurfs up to his board, which happens to be upside down, hops back on, and keeps on riding. Pat and Wingnut are always bickering about longboarding vs. shortboarding. Pat gave the longboard a try. He said, ‘Did I look cool or what?’ Only a week out of California and already living their dream of an endless summer.”] - Gary Hoey, “Pipe” (from The Endless Summer II)

[Clip of William Shatner, James Doohan, Leonard Nimoy, George Takei, and Marcy Lafferty from Star Trek: The Motion Picture] - Jerry Goldsmith, “A Good Start” (from Star Trek: The Motion Picture)

- Jerry Goldsmith, “End Title” (from Star Trek: The Motion Picture)

I never saw Mr. Majestyk, but I like how the pompous, very early ’70s drums in Charles Bernstein’s Mr. Majestyk main title theme are straight out of Johnny Pearson’s “Heavy Action,” the 1970 library music track that’s been the Monday Night Football theme since 1989. Every time I play back “Majestyk Main Title,” I keep expecting to hear Al Michaels say, “To the 30! To the 20!”

I never saw Machine Gun McCain, but the late Ennio Morricone is my favorite film composer from what’s known as the Silver Age of film scoring, so I can sing a couple of bars from Morricone’s “The Ballad of Hank McCain” in the weird voice of that British vocalist who pronounces “give” as “geeve” and sounds like half Homer Simpson, half Eric Roberts right after they took his thumb, Charlie! (Have you tried singing “The Ballad of Hank McCain” in Lupita Nyong’o’s Tethered voice from Us? I have. It’s fun.) The same goes for the early Louis Malle flick Elevator to the Gallows. I’ve never seen any of Malle’s movies, but I’m familiar with the sultry score Miles Davis composed for Elevator.

That’s because before I ran Accidental Star Trek Cosplay, the blog that’s the source of my Disqus username, I ran an internet radio station that streamed music from film and TV scores. My station stemmed from having enjoyed listening to scores by Morricone and Danny Elfman while also listening to a lot of De La Soul (R.I.P. Trugoy), A Tribe Called Quest, Digital Underground, The Pharcyde, and Prince. “Générique” from Elevator, which I included in “This Will Clear Out All the Bad Toxins,” happens to be only one of two Miles tracks I put into the station’s rotation. The other Miles track was “Spanish Key” because of its presence in Collateral—it’s the tune a washed-up trumpeter (played by Michael Mann project regular Barry Shabaka Henley) and his jazz band pretend to be improvising on stage, and the Tom Cruise assassin character knows right away that this trumpeter he’s assigned to kill is a bit of a sham because the tune sounds exactly how it sounded on Bitches Brew—and “Spanish Key” was part of a daily two-hour block of tunes that were needle-dropped into Mann movies, Spike Lee Joints, Scorsese Pictures, Homicide: Life on the Street, The Wire (R.I.P. Lance “This… is bullshit!” Reddick), and Adult Swim’s The Boondocks.

I’ve archived some of my old station’s content from the mid-to-late 2000s on my HearThis account. If you asked my mid-to-late-2000s self from those archived shows if he saw any of the movies whose soundtrack CDs or downloads he grabbed music from, my younger self would say, “Only about half of them. Maybe only about 40%. My station does a Bollywood lunchtime hour on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Out of all the Bollywood movies whose songs I’m rotating, I’ve seen only one: Bluffmaster! starring Abhishek Bachchan and Priyanka Chopra.”

That’s why the Solute gift exchange is good for me. It helps me to cross a few movies off my bucket list.