You might have seen this headline and asked yourself why I would take the time to write an article about such a middle-of-the-road radio-friendly rock band. The answer is equally simple: Because for a time– perhaps, on this album, for the last time– Everclear were anything but that.

Frontman Art Alexakis had kicked drugs before Everclear was formed1, but the pain that led him into his addictions is very much evident in the lyrics and themes.2 Robert Christgau’s review of Sparkle and Fade has a searing line: “Its cast of struggling souls is evoked by somebody past pitying himself–somebody who’s been around the block so often he’s finally learned that compassion is for other people.”

(1 – 1992, with Scott Cuthbert on drums and Craig Montoya on bass, the lineup that recorded debut album World of Noise in 1993. Cuthbert was replaced by Greg Eklund before Sparkle and Fade was recorded; this trio was the lineup for Everclear’s biggest period of commercial success. Eklund and Montoya left the band in 2003; Everclear is essentially an Art Alexakis solo project now, with a rotating series of musicians backing him.)

(2 – If you want more concrete examples of that pain, read the “Early Life” section of his Wikipedia page. It’s not fun.)

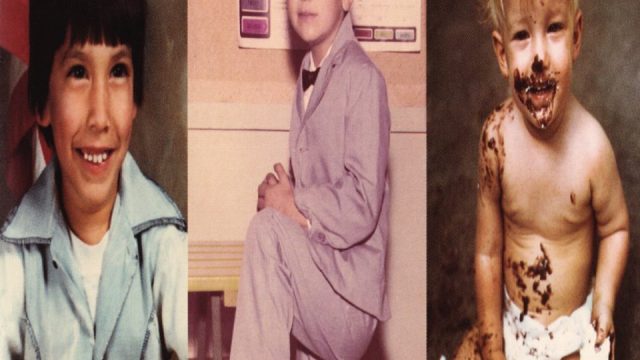

Even the cover art takes on its own form of heartbreak when juxtaposed with the lyrics and themes: photos of the three members of the band as children in happier, more innocent times. Contrasted with the lyrics about feeling fucked up, strung out, and self hating, it implies a question Adam Sandler would ask more bluntly on one of his album titles: What the hell happened to me?

Two years prior, Morphine made an album (the phenomenal Cure For Pain) that captured the feeling of being on heroin. Everclear made an album about why you would get on heroin. And that album is a nasty piece of work (complimentary); rugged and raw, brutally honest, and emotionally as laid bare as the veins once tapped to escape those emotions. It’s not quite simple enough and fast-paced enough to call it punk– and, despite being a Pacific Northwest power trio in the grunge era making raw and emotionally bare music, the Nirvana comparisons aren’t quite accurate, either– but the emotional nakedness and rawness of the sound make it at least spiritual kin to both.

My three favorite songs on the album all hit those feelings of self-loathing and the associated emotions hard. “You Make Me Feel Like a Whore” lays it as bare as can be in the very title. (This article’s titular line comes from this song, directly preceding the song’s title in the chorus.) I have no idea if the lyrics are about heroin or… some kind of relationship, although certainly not a healthy one, if the title didn’t give that away. It sounds like Alexakis is singing about someone he’s infatuated with who treats him like garbage because she can and he’ll still keep coming back, which, if not exactly about heroin, furthers the self-loathing he already feels:

I hate the way I am around you

I’m so nervous and weird

Sometimes I feel like I’m breathing underwaterYou treat me like I am on fire

Like I’m something to eat

You make me hate what I see when I see me

Our narrator is aware enough of this that he can’t decide what he wants; the final two choruses are back-to-back, and the first one starts “Yeah, I dream of the day / When I can make you pay”– flipping the title sentiment back around at the end: “Yes, I live for the day / When I can hear you say / You make me feel like a whore.” But then the last one goes back to “Yes I dream of the time / When I can make you mine.”

Maybe it is about heroin and the struggle between loving how it feels and hating how it makes you feel. Either way, it’s a nasty piece of punkish energy that vomits all these negative feelings out and forces you to deal with them. It’s great.

“Summerland” and “Strawberry” are my other two favorites. “Summerland” is an up-tempo song, another one about escape, the dream of so many self-loathing people, addicts or not: The desire to get away from it all as a substitute for being unable to get away from yourself. The first verse makes the substitution as clear as can be:

Let’s just drive your car

We can drive all day

Let’s just get the hell away from here

For I am sick again

Just plain sick to death

Of the sound of my own voice

The narrator is speaking to someone (presumably a girlfriend) and imploring them to escape with him; even though he’s sick of himself, he still thinks maybe his problems can be solved in a new location: “No one here gives a fuck about us anyway.” Summerland may, indeed, be a name on the map, but it’s possible Alexakis is using it as a metaphor for heroin, considering how the last two verses end:

We can live

Live just how we want to live

No one here really cares about us anyway

We can be

Everything we want to be

We can get lost in the fall, glimmer, sparkle and fadeForget about our jobs at the record store

Forget about all the losers that we know

Forget about all the memories that keep you down

Forget about them

We can lose them in the sparkle and fade

This makes it seem more evident that the “sparkle and fade” of the album’s title is the experience of using heroin and coming back down (or not coming back down).

“Strawberry” is much more explicitly about the struggle to stay off heroin and not relapse. Despite the challenges like his fucked-up feelings (“Never want to think about the things that happened today”) and the friend using in front of him (“You tie your arm and / Ask me if I wanted to drive”), the chorus makes clear that Alexakis knows the stakes: “Don’t fall down now / You will never get up.” And the final verse makes clear, even knowing the stakes, where this all ends:

The last thing I recall

I was in the air

I woke up on the street

Crawling with my strawberry burns

Ten long years

In a straight line

They fall like water

Yes, I guess I fucked up again

Two more songs I want to touch on get into the personal tragedies that fuel so much of the pain that leads to use. “Nehalem,” presumably named after the small Oregon coastal town a couple of hours outside of Portland, is one of the most up-tempo songs on the album, with Alexakis’ narrator singing to a girlfriend or lover, possibly now ex, opening with “There is this rumor about / They say you’re leaving Nehalem” and then immediately hitting with the reason why: “Ever since our baby died / You’ve been seen with another guy.” I am not certain if this is based in a real story or not, but I don’t really need to explain the tragedy of a dead child to you, and even the narrator seems to understand, as he moves through the stages of grief throughout the song: the denial that it’s just a rumor, anger (“The whole damn town is talking now”), bargaining (“Hey don’t you want me to go? / Hey don’t you want me?”), and eventually landing on acceptance: “Yeah, I know you need to break away” … “I know you’re leaving me / I know you’re leaving Nehalem.”

The story of “Heroin Girl” has more literal detail than many of the other songs, but still captures the feelings behind those events. Alexakis starts singing about the titular girl over a simple guitar riff, and then the drums and tempo kick in when he sings “I wish I could go back.” The next verse makes it clear why Alexakis cherished her, even if the “heroin” was as important as the “girl” in the title:

She’d do anything to give me what I need for my disease

She’d do anything

I can hear them talking in the real world

Yeah, but they don’t understand

That I’m happy in hell with my heroin girl

The heroin girl is Alexakis’ only respite in a world and life full of poverty, tragedy, abuse, and pain.

And then in the final verse, the literal details come in with stark reality and devastation:

They found her out in the fields about a mile from home

Her face was warm from the sun but her body was cold

I heard a policeman say, “just another overdose”

Just another overdose

When Art Alexakis was twelve years old, his brother George died of a heroin overdose. The final two lines above are from a real incident, what Alexakis overheard a cop say about his brother.

Later that year, Art Alexakis’ girlfriend committed suicide. She was 15.

What Sparkle and Fade succeeds at more than anything is to communicate not just what it feels like to be on heroin, or what it feels like to be an addict, but why someone would turn to heroin– the depths of self-hatred and the pain of tragedy Alexakis must have felt to desire so badly to run away from himself, that heroin seemed like the only answer.

It’s hard for me to believe the same band would make So Much for the Afterglow just two years later. It’s so placid and sterile by comparison, as though an ironic embrace of all Sparkle and Fade rejected had accidentally become an intentional one. I suppose the success of “Santa Monica,” the biggest hit off the album and the least overtly fucked-up song about fucked-up people3, might be responsible for that; second-biggest hit “Heartspark Dollarsign” also presaged it with its worryingly literal lyrics.

(3 – although even there the chorus is “swim out past the breakers, watch the world die.” Even on a relatively placid, hooky song, Everclear was still fantasizing about nonexistence.)

The songs on Afterglow are mostly drained of their punk energy, and where they have any, they are completely lacking in any subtlety, metaphor, or even feeling– as Pearl Jam once wrote, “trading magic for fact, no trade-backs.” No longer did they feel like a whore or feel like they fucked up again or feel like leaving behind their jobs and the losers they know and running, running, running from it all. Now they just straight-up told you about welfare Christmases and absent fathers. (I could write an entire separate column on “I Will Buy You a New Life,” a song entirely devoid of any… well, life, and lazily literal and lazy on the rhyme scheme to boot.) But on Sparkle and Fade, Everclear didn’t tell you the facts of a shitty upbringing: They told you how it makes you feel as an adult, how it screws you up and makes you hate yourself and how the things you pursue to chase away that feeling end up making you hate yourself even more.

Maybe Sparkle and Fade proved too personal and exhausting, emotionally draining in a way that’s evident on record, for the band to go there again. (I suppose, to borrow from an idea wallflower has expressed about this film, that makes it their Husbands and Wives.) Given how life treated Art Alexakis before Everclear, I can’t really begrudge him that, but I can regret that he couldn’t find it in him to make more music this raw and real. For one shining album, Everclear showed that they could make music as visceral and evocative as anyone could of the pain of being alive.