Victor Fleming, 1939. Ingmar Bergman, 1957. Mel Brooks, 1974. Francis Ford Coppola, also 1974. How many directors, particularly post-Golden Age and collapse of the original studio system, released not just two films in the same year, but two great films, if not their two best. (Maybe someone could make a case for Hitchcock in 1954, Spielberg in 1993, or Soderbergh in 2000, but I don’t think these represent those directors’ best work.)

All these names get tossed around in discussions about best one-two punches, but there is one director who doesn’t get brought up as often, though he ought to: George Romero, 1978. Just a few months before the European premier of his classic Dawn of the Dead, Romero released Martin, a film that’s been mostly forgotten outside the circle of critics and horror aficionados. Those in the club, however, know that the Godfather of Zombies may have done his best work beating Twilight to the punch with this small-scale look at a disaffected youthful vampire who’s just unlucky in love.

That last part is selling Martin a bit short, because it’s a lot of other things, too: this is, after all, George f’n Romero. It’s also a deep dive into late 70s malaise and urban industrial decline. It’s a meditation on fantasy and reality, a vampire film in constant dialogue with a deconstructed version of itself. It’s a cruddy bit of social realism grafted onto a bloody horror fantasy, or maybe the other way around. It’s about the ways older generations cling to familiar rituals while younger generations search for new ones, though it’s likely neither will save us. It’s about the commodification of loneliness and the way popular culture exploits authenticity, while itself guilty of those very things. It’s unevenly acted and weirdly paced, and not all the scenes work, and somehow this just amplifies the uneasiness, the sense of despair that hangs over the whole film. And – even considering the famously blunt finale of Night of the Living Dead – Martin has the most abruptly brutal ending of any of Romero’s films. As much as I love Dawn (and Night, and Day, and especially The Crazies), my heart belongs to Martin.

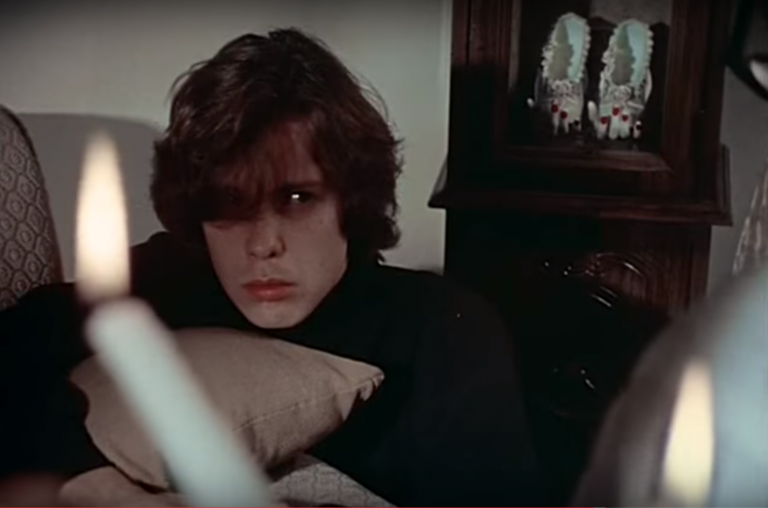

But for the horror elements, the setup is the platonic ideal of a 70s indie film: Martin (John Amplas) has been sent to live with his elderly cousin Cuda (Lincoln Maazel), a Lithuanian immigrant who makes him work in his grocery store as a delivery boy to keep him out of trouble. Cuda himself lives with his granddaughter Christina (Christine Forrest, later Romero’s wife of nearly forty years), who feels trapped in the twin prisons of Braddock and her conservative household (she’s not allowed to have a phone) and tolerates her thuggish boyfriend (Tom Savini) as a possible ticket out of town. Meanwhile, the novelty of having a new young man around the store, even one as awkward and pimply as Martin, sparks the interest of a bored and sexually frustrated housewife (Elyane Nadeau). Martin, in turn, finds his only real outlet in a local talk radio show, where he soon becomes a popular, albeit pseudonymous caller. The film establishes these relationships early on, then continues to tease out new layers and subtle shadings among them.

But there’s a twist: Martin also murders people and drinks their blood. Whether he’s a “vampire” is beside the point, because both he and Cuda believe that he is, that it’s a curse running through their family, and frankly, the dead don’t care either way. Martin claims to be an eighty-four-year-old man, but there are no fangs and no bats. He walks around in daylight, eats garlic, waves off crucifixes. Both Martin and Martin have some fun at the genre’s expense, as when he dresses up as a Halloween-store Dracula to play a prank on Cuda: the vampire playacting as “vampire”. Meanwhile, the bodies that pile up are all too real.

One of the film’s major themes is the allure of the capital-R Romantic, and how it only makes the mundane world around us look even more pathetic and suffocating. Romero’s Braddock is, to riff on Thoreau, a town full of people “leading lives of quiet desperation.” The houses are all yellowed linoleum and flower wallpaper, the clothes are drab, and the sky is overcast. Smokestacks line the horizon. Drug dealers hang out at the playground, and the Catholic mass takes place in an empty attic since their church burned down. Even the “mansion” that Martin breaks into for the film’s most extended action sequence is the kind of “mansion” that can only be built by people with no taste at all, a horror of secondhand shag carpet. Donald Rubenstein’s gorgeous, operatic score (the best in any Romero film… sorry, Goblin!) seems to hover above, offering us glimpses of some inaccessible dreamworld.

The decline of the Catholic Church is an especially sore point for Cuda, who wishes he could find someone willing to perform an exorcism on his monstrous cousin. When he suggests this to his young parish priest, a delightfully obtuse George Romero (!), it’s everything for the priest not to choke on his wine from laughter. Can we blame him, though? Romero’s Braddock may be a purgatorial nightmare, but what Cuda is suggesting is an actual Hell. The only character with what appears to be a vibrant inner life – Martin has either dreams or flashbacks in which he becomes the dashing vampire seducing a woman in white, filmed in a lush black-and-white for some of the best compositions in Romero’s career – also happens to be serial killer, at best.

Speaking of those kills, they are brutal. The violence in Romero’s zombie films was enough to earn Dawn an X rating from the MPAA, but there’s something clearly fantastic about the way his painted zombies chomp on flesh and tear people apart: it’s visceral (sometimes literally), and it can make you squirm, but these are fantasy monsters. The violence in Martin is more deeply uncomfortable because it’s so plausible. Vampire or not, Martin kills with razor blades, blunt objects, and chemicals. He whimpers apologies to his victims as the life drains from them. His violence against women – his usual target, the only people he can overpower – is tinged with a sexual dysfunction so unnerving that it feels like he’s violating more than their lives.

This gets into one aspect of the film that’s aged best, if not too well: Martin’s quasi-celebrity. Without a peer of any sort – Christina is kind but thinks Martin is delusional, Cuda knows Martin’s secret but is hostile – Martin bares his soul directly to a radio talk show host, live and on the air. The host, gleeful at having what he thinks is a chatty mental case on his hands, dubs him “the Count” and prompts Martin to keep divulging the more salacious aspects of his story – “the sexy stuff” – which Martin obliges. It’s a deeply unhealthy, parasitic relationship, where one lonely participant hides behind a pseudonym to bare his ugliest self in public, while the other prods him with semi-ironic, disdainful glee. In other words: the Internet.

I won’t spoil the ending except to say that it ends the only way it can, which doesn’t make it any less shocking. Romero still finds ways of inserting bitter ironies into the final moments, as if not content to let the generic ending (in the literal sense: demanded by the genre) blunt the movie’s tricky tone. Martin may not always reach the delicious conceptual highs of Dawn, which is a more accomplished film in most respects, but no other Romero film gets so deeply under my skin.

On a personal note, I was guided to Martin by the AV Club over fifteen years ago. Over the years it was a constant and familiar presence in the site’s articles and lists, becoming, like the films of Weerasethakul and the music of Dawes, one of those pop culture items around which the site seemed to coalesce in happy agreement.

Here’s that 2002 review, from Keith:

A sort of Dracula filtered through Taxi Driver (which was filmed the same year), Martin touches on any number of post-Vietnam ills (urban decay, drug addiction, crises in faith) without overstatement, allowing for a deeply considered exploration of horror’s ability to comment on society, a sort of belated answer to Peter Bogdanovich’s Targets.

Here’s Noel:

As much a mood piece about urban decay and the absence of real magic in the world as it is a conventional horror film, Martin is disturbing on multiple levels, and serves as a potent distillation of Romero’s vision of a world divided into predator and slightly scarier predator.

Here’s Katie:

…the unsung masterpiece Martin (1977) [is] an ahead-of-its-time character-driven drama/horror hybrid of the sort that re-emerges, and is hailed as a new innovation in the medium, every couple of decades or so.

And here’s Ignatiy:

It takes perverted ingenuity to turn something as eroticized and aristocratic as the vampire archetype into a study of alienated working-class boredom, and plunk it down into the unscenic, post-industrial environs of Braddock, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Romero’s longtime home base, Pittsburgh. (…) It’s the ordinariness that makes it so claustrophobic. This points to what made Romero so special: He used the premise of horror to trap characters in the places we ourselves wish to get away from.