In 2017, U2’s Pop celebrated its 20th anniversary, a milestone completely ignored by almost all of the general public and by U2 as they toured in support of the 30th anniversary of The Joshua Tree. Not that that’s surprising; their most explicit foray into electronica and, yes, “pop” was commercially and critically rejected, and the band felt they didn’t finish to their satisfaction, so nobody really wants to remember it. But one person did seem to notice and celebrate this milestone, and that’s art-rocker extraordinaire St. Vincent (from here on referred to by her real name, Annie Clark). In 2017, she released Masseduction, her most explicit foray into electronica and, yes, pop. It received the popular and critical support that Pop was denied, but it almost every respect besides reception, it reads like a perfect companion piece to Pop. Both albums walk and talk like sellouts, but there’s little beneath the surface that suggests they were made to be palatable for the general public.

Aesthetics

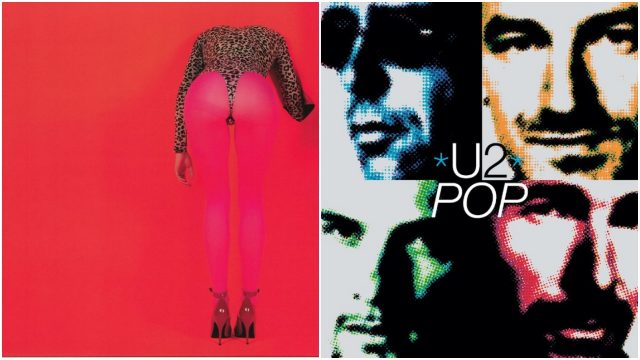

Both albums see their artists ostensibly moving away from rock and “going electronic”, complete with fresh blood behind the scenes (Pop being produced by the team of Flood, Steve Osbourne, and Howie B. and Masseduction being produced by pop kingpin Jack Antonoff; Flood even gets a “thank you” in Masseduction‘s liner notes). Of course, never mind that Zooropa is more of a departure from rock than Pop could ever dream of being or that St. Vincent is as much a “pop” album as Masseduction, this is just the public perception. And the public perception is likely what doomed Pop. When the “Where the Streets Have No Name” guys are making techno and dressing like the Village People, the whole enterprise can’t help but come off like a cynical provocation to get a rise out of people (not helped by the confused “satire” of premiering the album at a K-Mart). Clark, meanwhile, so stubbornly marches to the beat of her own drum (as evidenced by the first single of her previous most mainstream album containing the line “take out the garbage, masturbate”) that whatever shift she could make would likely be met with “sure, why not?”. Clark is just cool, while the window on U2’s coolness passed before Pop came out. But any concerns about coolness take a back seat when you listen to the actual albums. These are almost embarrassingly wounded, confessional albums dressed in pop-art garb, the synths serving the function of what most would use a solo acoustic guitar for. Masseduction‘s cover art provides a neat metaphor for both albums; there may be bright colors and a kitschy veneer, but more important is that they’re showing you their ass.

Openings

Opening statements are important, and Masseduction has a doozy. Within 30 seconds of track 1, “Hang On Me”, Clark announces “the void is back and unblinking,” and the quavering in her voice really makes you believe that. “Hang On Me” takes the form of an anguished phone call Clark is making to an ex-lover, begging for something like reconciliation because she has no faith in her abilities to make it on her own (she says she’s “not meant for this world,” and that checks out). Sure, there’s a synth and drum machine behind her, but the backing is so spare that it’s as if Clark is performing in front of the void. From the very start, she’s telling you that this isn’t her pop album, it’s her really sad one.

The void is present in Pop’s first track and single, “Discotheque”, as well, even if it’s not named. There, the void is a general gnawing emptiness, one “you can push but you can’t direct” no matter how much frivolous, bubblegum activity you throw at it. The trick it pulls is that the production is so high-energy and fun that you start to buy into the lie that this is helping you, that bubblegum can fill that hole deep inside you. Then Bono hits you with “you take what you can get ‘cause it’s all that you can find / oh you know there’s something more,” and the void really is back and unblinking.

First, A Note On Satire

One of the main roadblocks to people appreciating Pop at its release was the impression that it was just another postmodern gag from U2 after six years of nothing but those. And the album’s unambiguous lowpoint, “The Playboy Mansion”, reeks of half-hearted stabs at irony and satire. The problem with that song is a lack of point of view. At the halfway point, it starts trying to be about the search for spiritual meaning in consumerist society, but the first two verses are clearly just Bono spouting awful punchlines about the topics du jour (including, but definitely not limited to, OJ, Michael Jackson, and plastic surgery) he thinks are clever. It’s just satire without a guiding light, and Bono is not strong enough to pull that off. Compare it to “Miami”, which is often lumped in with “Mansion” as an embarrassing misstep. “Miami” is about the scuzziness of the titular city, sure, but it’s mostly about its narrator, a tourist who “only went there for a week” who actively participates in and encourages the degradation around him (his crimes range from buying gaudy suits to maybe being involved in amateur porn). He fancies himself a wry observer, but he’s no less a monster than anyone he’s describing. The most cathartic moment on the whole album is when Edge’s solo kicks in, his shredding so violent it seems to be seething with contempt for this man and the awfulness around him. If the song was just “wow, Miami sure is crazy”, it would be lame, but locking into this angle on that subject makes all the difference in separating “Miami” from “Playboy Mansion”.

Clark mercifully takes her lessons for the album’s most arch songs from “Miami” and avoids easy targets in favor of a bit of self-criticism. There are few easier targets than America’s addiction to pills, and so “Pills” coming as track 2 of Masseduction puts one’s teeth on edge. It doesn’t help that the chorus promises pills for everybody and every occasion in the sing-songy manner of a narcotized housewife, an angle that’s been well-trod since “Mother’s Little Helper” 50 years ago. But the verses quickly reveal that this isn’t a tired social commentary (Clark even said to Pitchfork that she finds “finger wagging songs” to be “condescending to the audience and just a bummer to listen to”) so much as it is a portrait of how Clark and only Clark is living. The pills are fueling her burning-the-candle-at-both-ends existence, getting her from stage to stage, city to city, and she knows she’s bound to crash soon. But when the crash comes, it’s unexpected and beautiful, the tempo slowing down to a blissful crawl as Clark rewrites “The New Colossus” and draws near every fellow lost soul. What initially seems like a finger wag at society and their dang medication instead becomes a medication-induced call for community.

If there’s an easier target than pills, it’s probably those dang Los Angeles phonies, which makes track 5, “Los Ageless”, pretty concerning. Luckily, it’s Masseduction‘s own “Miami”, a city song about the person who thinks they’re above the city. What’s more important than the descriptions of shallow LA women is Clark’s initial mantra, repeated at the end of the first two verses;

“But I can keep running.” She’s not like those women, because she has agency and is free to go. Much like “Miami”‘s narrator, she believes herself to be a passive observer of this town, calling out the bullshit but not getting her hands dirty in the process, but of course, she isn’t. She even starts making excuses for herself, saying she can’t run because “I just follow the hood of my car,” but by the bridge, she can’t even keep that up. The chorus is even more revealing, not based around jabs at L.A. but the line “How can anybody have you and lose you and not lose their mind too?”. It becomes clear there that this is a love song gone sour, Clark falling for an L.A. woman and foolishly thinking she can take the girl and leave the city. And then, following the final chorus, the song slows way down, the glossy instrumentation gives way to mournful pedal steel and strings, and Clark literally clarifies what she’s just sang as “I try to write you a love song / But it comes out a lament.” And much later in the album, with the much friendlier city song “New York”, Clark even considers a move to Hollywood now that the relationship is over. What seems like “biting” commentary is really just emotional distress, and there’s a lot more where that came from.

God

Much more than an “electronic” album, Pop is a crisis-of-faith album, all about the absence of God and how people try to deal with it. For most of the album, people deal with it with empty partying or By track 3, “Mofo”, Bono is already “looking for the baby Jesus under the trash”, because he can’t find him in the empty partying and sex of the previous two songs. That’s followed with “If God Will Send His Angels”, a deeply bitter song where Bono moans about God and Jesus’s names getting whored out in pop-culture and Christmas specials while all the miserable people on Earth are left to suffer. The “if” in the title is key; Bono really doesn’t seem to have much faith in those angels coming down anytime soon and ending all this. And then that goes straight into “Staring at the Sun”, where Bono rails against the empty words of religious fundamentalists (“Those that can’t do often have to preach”) and how they get us no closer to God or to peace. But that’s all table-setting for the attack of “Please”, in which the Troubles are summed up as the Irish enacting a pathetic mockery of God’s word, leaders on both sides being too busy praying to an absent God to actually deal with the massive tragedy left in their wake.

God is just as absent in Masseduction, but here, His lack of presence initially seems to mean that everyone can have more fun than if He was looking. If Bono is distraught by perversions of the Lord and his messages (just listen to the contempt he spills into “your Sermon on the Mound from the boot of your car” in “Please”), Clark seems to relish the opportunity for a bit of light (or sometimes extreme) blasphemy. The first verse of the title track alone opens by namechecking Charles Mingus’s The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady and goes onto describe “nuns in stress positions smoking Marlboros.” And that’s before the verse about “teenage, Christian virgins holding out their tongues,” in which communion and blowjobs are one in the same, and those same virgins’ “paranoid secretions falling on basement rugs.” And all that is before “Savior”, in which Clark dons a nun’s habit for a sex game and sings “Hail Mary pass, ’cause you know I’ll grab it.” This is a world gone mad without God, and damnit if that doesn’t turn Clark on.

Of course, it’s only fun and games for so long until you really need God, and Clark needs Him in a big way by track 9, “Fear the Future”. This is one of the most Poppy songs on the album, built around the deafening wall of synths from “Mofo” and taking the form of Clark pleading to God for something in return for her lifetime of service. More specifically, she’s looking for the “answer”, the thing that makes all the time spent with Him and all the things that happened under His watch (including her lover bottoming out) worth it. The instrumentation is loud enough to wake God on its own, and Clark’s cries are impassioned, but in the end, she’s no closer to getting that answer, and is left to fear the future all on her lonesome.

Sex

The 90s were about the last time U2 could pull off “sexy” and not look like idiots (never forget “sexy bewwwwwts“), and there are a few songs on Pop that try their hand at sexy. But for all the breathy vocals and soft instrumentation, the sex these songs are describing is totally drained or passion or worse. “Do You Feel Loved” is the most explicit song on the album about sex, with its characters indulging in what sounds like S&M, but it all seems empty and going-through-the-motions, like an extension of the “sweetest lies” Bono is feeding his partner. But at least he’s doing an okay job faking passion there. In “If You Wear That Velvet Dress”, he sounds so worn-out that it’s obvious that his teasing promises of future sex (and reminders of past infatuation) are a last-ditch effort to salvage a relationship that has given him no joy. He can’t even think far ahead enough to really promise what will happen if that velvet dress is put on, he just needs the possibility of future pleasure to be open. And then there’s “The Playboy Mansion”, which sees Hugh Hefner’s commodified, cartoonish image of sex presented as the treasure awaiting those who enter Heaven.

At the very least, Clark gets some enjoyment out of sex, which is more than Bono can say. She finds comfort in both adventurous polyamory, with the title track’s shout of “I can’t turn off what turns me on”, and quiet intimacy, with one of the few happy moments in “Young Lover” being Clark “lying on tiling” with her lover. But those are idealized moments for Clark, who’s just as likely to experience the unsatisfying bit of oral sex glossed through in “Pills” or, worst of all, the ultimately destructive psychosexual game in “Savior”.

“Savior” is possibly the skeleton key to both albums’ treatment of sex. In one respect, it’s “The Playboy Mansion” done right (it even opens with the same bit of parodic porno-funk), with its tying of the most cornball notions about sex to a religious metaphor actually working. And it’s also a continuation of “Velvet Dress”, if Bono kept making future clothing demands after the dress gambit worked. Clark dresses as a nurse, a school teacher, and a police officer, but none of it satisfies her lover and it certainly doesn’t satisfy Clark, with the outfits being both literally and metaphorically ill-fitting. But the choruses reveal that maybe the discomfort of these roles is the point; this is a way for Clark to become her lover’s Christ figure, to suffer for her lover’s sins and transgressions. No matter how hard Clark protests about this not actually helping the problems at hand, her lover keeps coming back to one word; “please”. This is the album’s most direct link to Pop, seeing Bono’s impassioned cry for peace in Ireland being used as a plea to continue an unhealthy sexual obsession (in pithier terms, it’s going from “get up off your knees” to literally making someone get on their knees). But Clark invests so much heartrending pathos into those “please”s that you see why she can’t say no to them, and why the cycle will never be broken. You can almost see why Bono doesn’t want any part of this.

Rock ‘n Roll

One gets the sense from Pop that Bono was maybe getting tired of the rock-star thing around this time. “Hold Me, Thrill Me, Kiss Me, Kill Me” from two years before already had a pretty cynical view of stardom, but at least it also emphasized some of the fun of it, whereas “Gone”, this album’s big song about being in a band, is too burned-out to see rock stardom as anything but a dead end. The verses are a laundry list of the worst aspects of fame, from the gnawing feeling that you don’t deserve what you’ve gotten to inadvertently hurting yourself and your lover, and the chorus is the almost suicidal-sounding “goodbye, you can keep this suit of lights / I’ll be off with the sun / I’m not coming down”. And there’s more of that fatalism sprinkled into “Mofo”, where Bono is “looking for a sound that’s gonna drown out the world” and failing, as well as “Discotheque”, where the quest to “be the song that you hear in your head” is a futile one.

Clark seems to enjoy being a rock star a lot more than Bono. “Sugarboy” is the negative image of “Gone”, reveling in the pure adrenaline and joy that comes from being on-stage and feeding off the energy of the audience. Clark makes the artist-audience relationship sound purely erotic, maybe even bordering on S&M with Clark happily feeding the audience suicide fantasies and becoming their “pain machine”. And in the title track, she almost seems to mock Bono’s frustration with his job with the pithy line “Oh, what a bore to be so adored.” But if Clark can abide by the on-stage life of a rock star, she can’t deal with the behind-the-scenes debauchery that often follows. For her songs on that subject, she seems to take as inspiration one particular line from Pop, specifically “Last Night on Earth”. That song is about a young woman living a devil-may-care lifestyle and seeming liberated by it, until the final verse hits the listener with the reminder that “she hasn’t been to bed in a week / she’ll be dead soon, then she’ll sleep”. There is an end of the line even for celebrities and their partners, and several of Masseduction‘s songs take place right near that line.

“Happy Birthday, Johnny” is one of the most overtly sad songs on the album, a spare piano ballad about an ex-lover on the skids. Clark describes images typical of rock star behavior, including trashed hotel rooms and idolized Jim Carroll books, stripped of all their glamour and fun, leaving only a dire portrait of someone destroying themselves. And it’s here where she really begins to doubt the allure of rock stardom, resenting how it’s pushed her even farther away from Johnny, leaving him alone to succumb to his vices (in other words, she’s hurt herself, she’s hurt her lover). Even her final bit of comfort to Johnny can’t do much, when she’s not there to make it a reality (she promises that it’s a matter of “when” he gets clean, but one thinks that he’s probably bound to join the “Last Night on Earth” girl soon). Not that even being there for him would guarantee his recovery. “Young Lover” comes later in the album and sees Clark trying and failing to help a lover who’s bottoming out right in front of her. If one is to believe that this song is about Clark’s ex Cara Delevingne, it paints a dire picture of her behavior, with mommy issues and fame leading to her “boozing on a midday,” zoning out on pills, and eventually ending up in the bathtub “with your clothing on.” And Clark can’t really deal with it no matter how close she is to Delevingne; her approach to stopping this starts with bitter sarcasm and ends with earth-shattering screams for her to wake up. It’s no shock that, after seeing all that celebrity can ruin, Clark finds herself disconnected from rock altogether, not playing a lick of guitar for the rest of the album. She even gets off the stage, enjoying a “Slow Disco” with her lover as a last goodbye away from the chaos of the celebrity lifestyle.

Closers

Both Pop and Masseduction end with spectacularly dark nights of the soul, showing Bono and Clark unable to keep up the pop veneer and the impression that they’re doing even a little okay. “Wake Up Dead Man” is one of the most brutal songs in the U2 catalog, Bono screaming and cursing at Jesus to do anything about anything, to the point of concluding with the suggestion of just ending all this and starting over. His voice is shot and the distortion over the vocals only emphasizes that, Edge’s guitar work eventually devolves into atonal shredding, and the only electronic elements are some random chatter and loops in the background, creating the perfect minimalist soundbed for guts-spilling.

“Smoking Section” isn’t quite as stripped-down as “Dead Man”, taking the form of a piano ballad with some electronic flourishes between the verses, but the relative polish does nothing to disguise the bleakness of what Clark is saying. She outlines various suicidal fantasies, of burning to death from errant sparks and of jumping off her roof, but what’s even more disturbing than the fantasies themselves is how she’s imagining them not because she wants to die, but because she wants to spite her partner. It’s hard to say a song is bleaker than Bono begging for the apocalypse, but a relationship so sour it numbs you to the idea of death is pretty heavy stuff.

But unlike Bono, having stared down that unblinking void, Clark at least has the strength to recoil from it. After her threat to jump, a heavenly choir, complete with organ backing, comes in and sings “And then I think / What could be better than love?”. This might just be the voice of God, finally here to save Clark from herself, and it leads her to say this; “it’s not the end.” This is ostensibly a moment of triumph, Clark taking control of her life and stepping back from the edge, while Bono is left only to scream in the gutter. But as she sings this, she doesn’t play relief or renewed energy, but mortal terror at the thoughts that have crossed her mind. Her voice cracks and warbles even more with each repetition of “it’s not the end” until she fades into the aether, while pedal steel guitar wails for her in the background. What’s worse, God not being there or Him being there and that still not being a comfort?