Whenever a bloated, overlong action movie gets inflicted on the viewing public, someone can be counted on to defend its existence by saying “it’s just a stupid action movie, you can’t expect it to be some kind of art film/Oscar-winning film,” which is the cinema equivalent of defending a taco made with pink-slime meat-resembling product and processed Cheez Whiz by saying it’s not a steak dinner. Our tastes vary with time–sometimes we want the steak dinner and sometimes we want a taco, and when we want a taco, we should get a good fuckin’ taco. Like anything else delicious, fulfilling, and awesome, a good action movie should be made well, and there are ways to make things well. The two films under consideration here, John Carpenter’s Escape from New York (1981) and Rob Bowman’s Reign of Fire (2002), have flown somewhat under the radar, and I suspect that’s because they embody the virtues of the lean, efficient action movie as compared to the bloated summer blockbusters of contemporary action cinema. (It’s no surprise that the best tacos are found in the little stands and hole-in-the-wall places that only a few people know about, too. If you want to go to Taco Bell, that’s easy.)

The fundamental virtue of clarity

“Make it clear” is the first rule of action filmmaking. At all moments, at all scales, if we can’t follow the action, something’s wrong; if we can’t figure out what’s happening or why it’s happening, something’s wrong. If there’s moral ambiguity in the characters, that’s a bonus but not the primary goal. Action movies work because all of us have a fight-or-flight instinct that some hundreds of millions of years of nature have bred into us and a few lousy thousands of years of civilization hasn’t changed that yet. Watching tense situations, imagining ourselves in them, is exciting; action movies and horror movies may be the only truly universal genres. (They have complementary methods, too; action movies depend on making things clear and horror movies depend on concealing things.) Politics, morality, aesthetics, even love can vary across cultures, but every one of us wants to run like hell when a big fucking rock comes after us.

On the scale of plot, a good action movie presents the situation immediately, and then starts the characters moving through it; Escape from New York does this as perfectly as I’ve ever seen (it ranks with Die Hard on this point), and Reign of Fire is damn close. Every moment in the first 15 minutes of Escape gives us a necessary piece of information–Manhattan as maximum security prison, the President crashing into it, the 24-hour deadline, Snake Plissken’s (Kurt Russell) rescue mission, the charges that will blow his arteries if he misses the deadline. Reign has an unnecessary opening sequence–it looks like it’s setting up a plot point but it’s never used–but after those first eight minutes, a quick montage lays out current events: dragons have taken over the world and forced the remaining people into hiding, and now the dragons are slowly dying out. In both films, that exposition is necessary for clarity; now we know what has to be done. Neither film has to explain anything more than that, and we’re off.

THAR BE SPOILERS PAST THIS POINT, MATEYS

Although I’m describing exposition like it’s a distraction, it’s actually necessary to an action movie, because it conveys what the obstacles are; it lets us know the tasks that face the characters and how they deal with them, making the action coherent and therefore interesting. Both these films are good with the initial exposition, but they’re also good at conveying information on the fly, dropping little details all through the movie so we know what’s going on. Escape shows an oil well in the middle of the New York Public Library, behind Harry Dean Stanton’s Brain; without slowing down at all, we know now how powerful he is in this world. (Stanton’s character is called Brain, it’s not like his brain is floating there in the library.) Reign shows all sorts of things that let us understand how Quinn and his community have survived for so long–Quinn mentioning the timing of harvests, the use of birds as warning signs, building a sprinkler system. None of these are explained beyond showing them, and they don’t need to be. Good action filmmakers make us active viewers, and that’s part of the pleasure; it’s an insult to automatically preface the phrase “action movie” with “stupid.”

Fewer things can fuck up an action movie more than trying to give the protagonists some kind of emotional stakes or (God help us all) some kind of journey. Usually this is done with the intention of making the protagonist more relatable and usually it has the opposite effect, loading the film with emotional and ideological assumptions that don’t need to be there. The most common form of this journey is the hero Overcoming His Fears to Become a Real Man; Reign of Fire does use this, set up in that first sequence. Whatever you think of its moral value (Sam Peckinpah’s Straw Dogs took us on the most harrowing form of this journey, precisely because it led into some incredibly morally difficult places), it does something deadly for an action movie: it slows things down and diminishes the intensity. It also makes the story less universal, and less effective. Again, not everyone will buy into the theme that killing makes you a man, but everyone wants to survive.

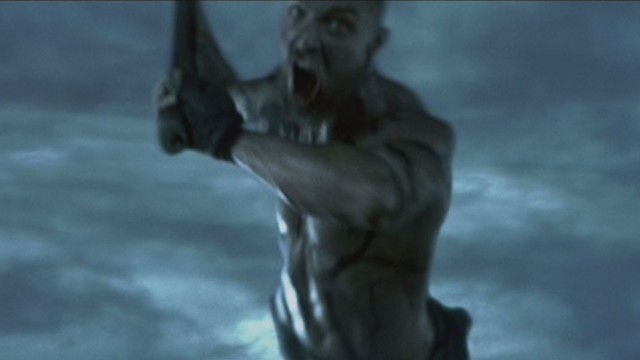

It’s a minor point that Reign of Fire uses that standard subplot, partly because it doesn’t take much time, but mostly because it handles another aspect of the story unusually well. A theorem that follows from the axiom of clarity: if you’re going to have conflicting protagonists, give them a good reason to be in conflict. In Reign, Quinn (Christian Bale) runs a small community based in a castle, and plans to simply wait while the dragons all starve to death, and then Van Zan (Matthew McConaughey) shows up as the leader of an American militia hellbent on hunting and destroying the dragons. In a lesser movie, Van Zan would be the ideal of manhood that shames Quinn into acting, or he’d be the psycho who will clearly get everyone killed. Here, though, it’s a genuine logical and moral dilemma. It’s established early on that Quinn’s community can’t count on the food to last the one or two more years they need, and Van Zan also makes a case much like Max Brooks in World War Z: humans need to reclaim their position as the dominant species. This balance, the sense of a genuine dramatic challenge rather than a plot expediency, is Reign of Fire’s strongest aspect. It’s helped enormously by Bale and McConaughey, who both play their characters as incredibly strong, emotional, and just a little crazy. More on this later, but it’s worth noting that both Reign and Escape from New York objectify the living shit out of their men.

Clarity in motivation is essential for the action movie entire; clarity in staging is essential for the action scene, and I will shut up about this when contemporary directors start doing it. This doesn’t mean an action scene has to follow the laws of real physics; it does mean that an action scene has to take place in a real space. That means, for example, that when we cut away from a person, that person is still there in the space and can’t magically disappear or do nothing. (Only editing allows so many action protagonists to fight six or more people at once–we only see them fight one or two at a time, and when the camera cuts away from the others, they just, I don’t know, stand around with their hands in their pockets or do their taxes or some shit. Equilibrium –another Christian Bale movie–has some particularly funny examples of this.) Once we lose a sense of where things are, we lose the intensity that makes a good action film.

Escape from New York and Reign of Fire both excel at keeping tracking of who is where, and what they’re doing. John Carpenter and his cinematographer, Dean Cundey, do a lot in Escape with foreground and background action, using deep focus to keep track of two things happening and the distance between them–watch Snake run on a train in the background while Brain runs interference in the foreground. Later, as the film turns into a straight-up chase, Carpenter uses our knowledge of where things are to make just the appearance of lights in the distance crank up the suspense. Over in Reign, Rob Bowman guides the film through five great setpieces. In particular, in the third, he does something so many post-apocalyptic films have tried and failed to do: he crafts an action sequence using medieval and modern technology, with helicopters, horses, parachutes, bows and arrows, computer imagery, binoculars, warning birds, radios, and rocket launchers. Bowman tracks everything so well that he can guide it to an incredibly thrilling climactic moment of Van Zan firing a rocket directly at Quinn, and we know exactly why he’s doing it (there’s a dragon right behind Quinn) and what will happen. In the fight with the final boss, Bowman tracks everyone’s position carefully, and pays it all off with a final shot of an explosive arrow zipping from left to right on the widescreen and tracking it with a pan of about thirty degrees; the geometry of the shot is pure thrill. These are sequences that engage both our primal instincts and our ability to think, and it’s so far removed from the bright flashy visual chaos of Michael Bay et al.; the most you can say about Bayhem action sequences is that they’re occasionally distracting in a pretty way.

Scale is the enemy of intensity and spectacle is the enemy of both

Coming back to Escape from New York after a long absence and too many contemporary action movies, I was struck by how minimal it is, in plot but more importantly in scale. Carpenter’s instincts were still those of the guy who made Dark Star and knew how to get things done on a budget. There just aren’t that many people in this film, not many settings, most of it takes place at night, and nothing is filmed for the sake of showing off. That’s, of course, why it works so well, and holds up so well: because there’s almost nothing here to distract from its relentless forward momentum.

The rise of the summer blockbuster has done so much to weaken the action movie. These films have increased their budgets, which means they’ve increased their scale and spectacle. That’s a fundamental mistake, because action movies do not run on scale but rather intensity. Spectacle is even worse for action movies, because they stop the movie’s pacing in order to give us time to appreciate all the money up on the screen. Mo’ money gets you bigger ‘splosions, more polygons in your CGI (which Bay often brags about), more characters, and every one of those things might look cool, might make the audience go “ooooo!” and might provide something you can make into a fucking collectible cup at Burger King, but every one of those things distracts from the momentum of the movie. I get more worried with every new MCU movie, because something that has the potential for so many different kinds of movies keeps getting dragged into this kind of large-scale spectacle-heavy genre.

If a drama requires competing visions of the good–that is, there are different ways for all participants in a drama to be right–action requires competing versions of strength; there has to be a way for all participants to win. (If, like Reign of Fire, you can throw in different definitions of winning, you have an action-drama.) That requires careful calibration of the strengths, and much more importantly, the weaknesses of all the players; another common failure in action films is the villain who is all-powerful in the first act and incredibly incompetent in the third. The drive of blockbusters to have ever-greater scale quickly destroys the balance between the participants, and forces the action to take on an even bigger scale. It’s no longer heroes vs. villains, but superheroes vs. supervillains; Infinity War looks like the MCU will escalate to superdupervillains. It’s no longer enough to fight for your life, now we have to fight for a city, or possibly the entire universe. (Damon Lindelof has written well on why producers find it necessary to increase the scale of their movies, and what that does to any kind of empathy.) When the scale becomes that big, we lose any kind of instinctive, empathetic connection to it. We can’t feel what the destruction would be like, we can only see it and be dazzled by it.

Escape from New York keeps the scale small enough, and keeps Snake human enough, to make us wonder about the outcome. He needs and gets allies, and he’s nowhere near all-powerful. (It’s a great touch that he loses almost all his utility-belt-type toys early in the action.) The countdown clock literally at arm’s length for the whole film restricts his options; when he threatens to torture Maggie (Adrienne Barbeau), Brain counters with “she doesn’t know exactly where he is, and if you don’t know exactly, precisely where he is, you’ll never find him.” It’s believable that he could fail, and believable that he could pull this off, and so we feel one of the fundamental pleasures of storytelling: we don’t know what could happen.

Once it gets the exposition out of the way, Escape from New York moves about as relentlessly and continuously as anything that side of The Raid ever has. There are no isolated setpieces, save for a WWE-style fight with nail-studded baseball bats; instead, every action leads to another action, finishing with a climatic chase down the bridge. This may be Carpenter’s best work, about as pure as five minutes of cinema can get, and it shows just how crazy intense an action movie can get because of its small scale. All that Carpenter needs to present is the relation of space and time, the objective is as simple as can be: Snake and the President have to get from one end of the bridge to the other in a few minutes before Snake’s arteries blow, and they keep hitting obstacles. Every single car, grenade, gunshot, or fight slows them down and drives the tension even higher, right up until the literal last second. (Carpenter and Alan Howarth’s propulsive score helps a lot here; I have more to say about this in the Soundtracking podcast.) You could go through a hundred billion dollars’ worth of effects shots in the last 34 years and not find anything more exciting than Lee van Cleef stepping in front of Snake and saying “the tape, Plissken.”

Although Reign of Fire belongs to the age of CGI and is much less of a small-scale production than Escape, it still has a good economy to its plot and scale. There are five setpieces (and only the first is superfluous) and two settings, and that’s all; if it doesn’t have the pure chase feel of Escape, it moves from one setpiece to another without any loss of momentum, with each one setting up the next. The dragons are only dealt with one at a time (although we do see a flock at one point), because, y’know, one dragon is scary enough, and enough of a challenge for the protagonists. I suspect that part of the reason Bowman keeps the action reasonably-scaled is his background in television, just as Carpenter had a background in cheap film production; Bowman was a director on The X-Files and his only previous film was its first movie. That kind of experience gave him the discipline in generating intensity from the elements of filmmaking rather than spectacle. Bowman takes care to make this an even fight; there’s the subtle indication of the tattered dragon wings that show they’re weakening, and the more direct weakness of the dragons’ poor vision at dusk. Van Zan knows and exploits this, and Bowman shows it with some good POV shots. Bowman also keeps the focus on this single community, and this single fight, and trusts us to get the stakes involved without bringing in anything else. It keeps the sense of stakes without sacrificing any speed or intensity.

“Being able to project this extraordinary iconography from the inside” is what Christopher Nolan said he was looking for when casting Batman, and it’s about as good a criterion as can be for what great action-movie actors do. Great action movie characters are not deep or well-rounded; that sort of thing belongs to novels and post-Shakespearean drama. Great action movie characters are icons, and they should be played as icons. The iconic performers in movies could convey so much by how they stood, and by the smallest gestures; it’s something that goes at least as far back as John Wayne. Garry Wills, in John Wayne’s America, discusses the Wayne pose in terms of Renaissance statuary; for me, the defining image of badassery in movies is Toshiro Mifune sliding his arms out of his sleeves in Yojimbo. These iconic performers take a life in our culture that goes beyond the screen, and become part of our psyches; Jean-Pierre Melville caught this when he said that a good movie should make you want to dress like the hero. (If you don’t want to dress like Alain Delon in Le Samouraï, I have nothing more to say to you, and I’m not sure if that’s restricted to men.)

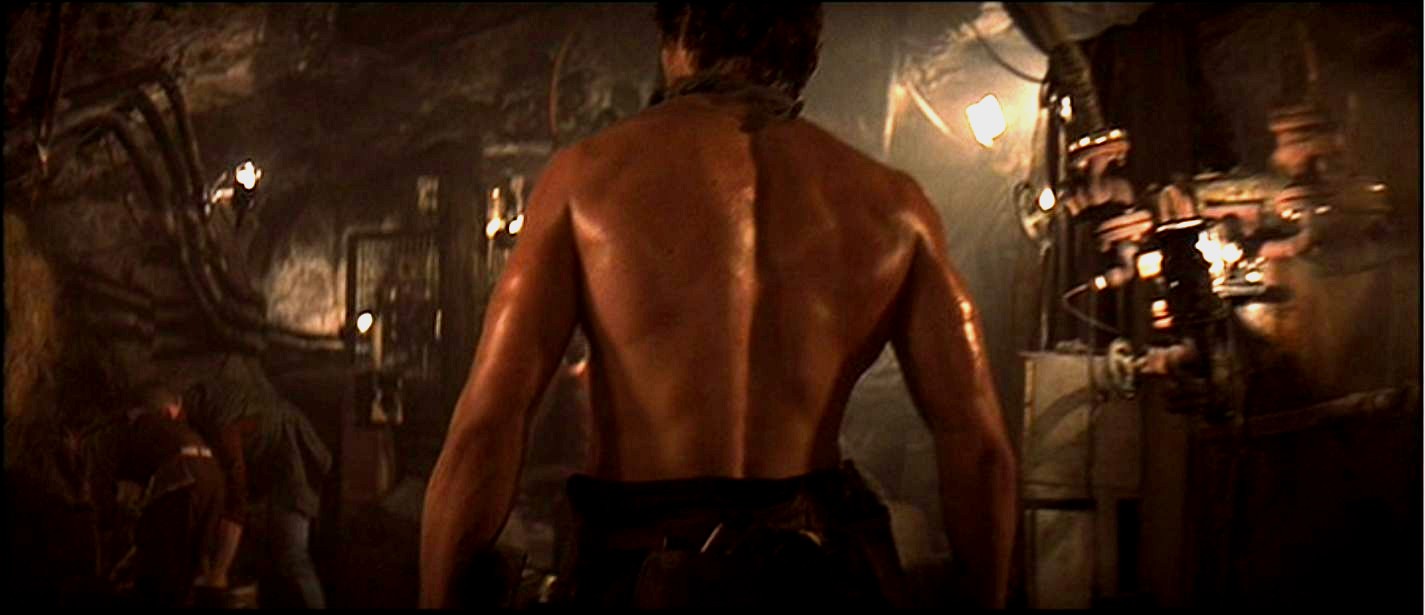

Bale and McConaughey both crush it on this point. They’re buffed up but not to Rock levels; you can believe it comes from a decade-plus of physical labor and no more processed food on the market. Bale’s physique, which was so much a threat and a machine in American Psycho, here is somehow almost comforting; he plays Quinn as someone who really will protect you at all costs. Bowman and Bale carefully give Quinn so many moments where he’s interacting with other people; his opening scene as an adult recalls the first trench scene in Paths of Glory; like Kubrick, Bowman introduces Bale shirtless and tracks him through a confined space and shows him greeting everyone. (It’s just as genuinely erotic here as in Kubrick.) Bale also brings in a unique kind of intelligence here, in that Quinn’s very smart but it comes entirely from experience. If we’re talking in archetypes, Quinn is the Farmer. His strength is never in question, and that’s necessary for the balance in the plot I mentioned earlier.

For his part, McConaughey makes Van Zan the Warrior, and it’s his best performance between Lone Star and True Detective, the one flickering light of hope in the dark years of the McConaughieval period. The glint in his eyes stays just this side of madness; he’s not Guy Who Will Go to Far, but he might be. (He sometimes comes off as a non-American’s image of an American, which had a particular resonance in 2002.) In one remarkable scene, he gives the speech about “pity the country that needs heroes,” and does it with his eyes filled with tears. It’s moving, because it makes us wonder what Van Zan would have been like without a decade of war behind him. He might have become a McConaughian slacker, but now he’s burned himself into this new creature, and he’s not fully comfortable with it. With just a few gestures and details, McConaughey imparts a sadness to this hypercompetent figure.

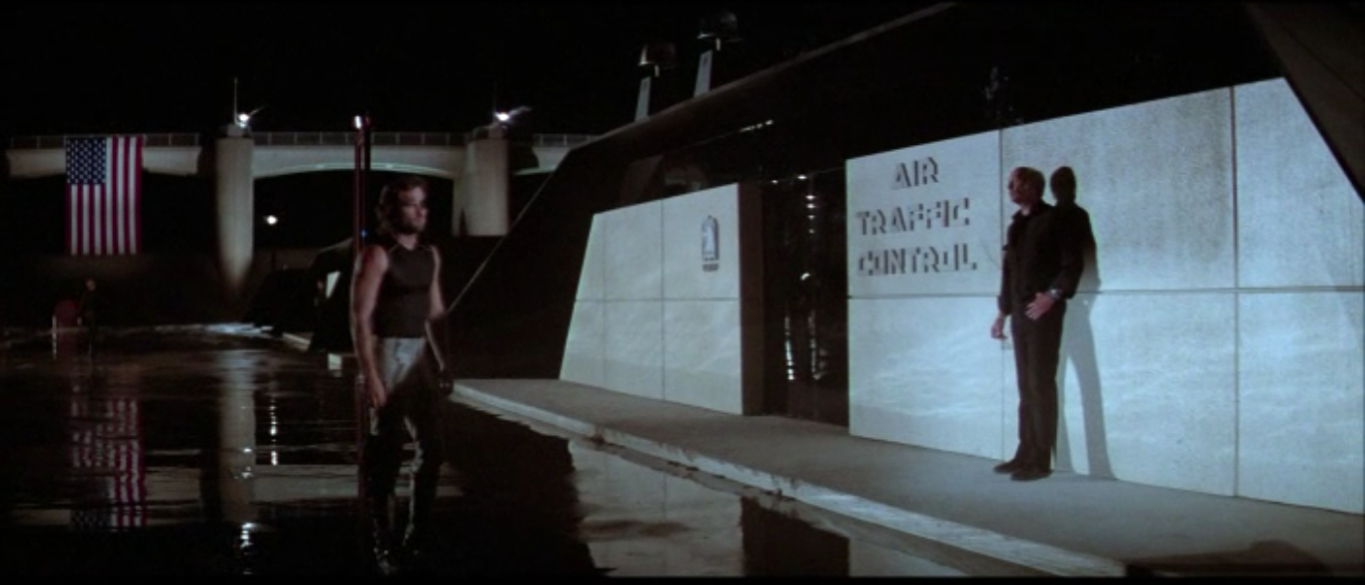

As for Escape from New York, you could subtitle it The Varieties of Masculine Ownage; only The Great Escape ranks higher in that respect. It’s difficult to type out this cast without making every middle name Motherfuckin’: Kurt Russell, Lee van Cleef, Ernest Mothe- (told you) Borgnine, ISAAC HAYES for the love of all that is holy, Harry Dean Stanton, Donald Pleasance. Everyone brings in the strength of decades of acting to their characters, the thing usually called “screen presence”–that ability to command your attention from the instant of appearance. van Cleef, in particular, doesn’t have much to do and doesn’t need to; he’s completely relaxed and in command at every moment. His last scene with Kurt Russell, the two of them outside and standing, talking, has a beautiful action poetry to it–the two gunslingers at the end of the fight. (Russell deliberately modeled his performance here on Clint Eastwood, so that makes sense. In Big Trouble in Little China, he would channel John Wayne.)

Russell, of course, has to hold the film together. He’s not as well-built as McConaughey or Bale, and his first appearance has him in scruffy hair and a beaten jacket. As an archetype, he’s the Trickster rather than the Warrior, appropriate for a guy named Snake, and something that fully pays off at the end. You can believe that it took Snake a long time to get caught, and you can believe he would be smart enough, as opposed to strong enough, to bring off this mission. Like Eastwood in his most iconic roles, Russell keeps his voice quiet at all times. It’s kind of intimate and certainly seductive; with his hair, grace, and soft voice, there’s something feminine mixed into this kind of masculinity.

The interactions here show how much the clash of masculinities gets you. As the President, Pleasance is clearly a guy who lives and works within institutions, but isn’t any less strong for that; watching his performance now, I kept thinking that I wanted him to play Dick Cheney, or maybe show up on The West Wing and own the entire cast. As the Duke of New York, Isaac Hayes seems to have stepped out of, well, an Isaac Hayes song. (“Ridin’ in a limo with twin chandeliers. . .”) Hayes plays a smart undercurrent of fear here; the Duke always knows what he says will be obeyed, but he also understands that’s not necessarily going to always be true. He’s the Pimp, and it is in fact tough out here for him. The final showdown between these two characters (“YOU ARE THE DUKE OF NEW YORK! YOU’RE A-NUMBER-ONE!”) has stayed in the mind of everyone who’s seen this film for a generation. You can see it (and with good reason, I’m sure some people can only see it) as a white authority figure defeating a black outsider, but I see two American Gods going at each other with automatic weapons, the kind of larger-than-life thing that only belongs on a movie screen. It’s the difference, again, between archetypes and stereotypes.

Both give us, humming all through their films, a wonderful, incidental pleasure of storytelling, the enjoyment of “realistic characters in unrealistic situations.” (This is JJ Abrams’ description of what he tries to do, and he’s been getting less successful at it.) Tell your story well, keep things on a plausible scale, and there will be all these little opportunities for humor and sentiment and you can convey that without slowing anything down. Many action movies regard humor and sentiment as something to be added to the story, almost like there’s a checklist (given how movies are produced, that might be true), and that will land as false every time, because it is.

All the humor and sentiment from these films comes from the story and the setting. Since there are so many children in Reign of Fire’s community, it makes sense that they’d have some entertainment, which here consists of Bale and Gerard Butler (as Chief Sidekick Redshirt) performing the climactic scene of The Empire Strikes Back, with a wonderful beat from Butler mugging to the kids and showing them his hand wasn’t really cut off. (This, by a wide margin, is Butler’s best performance; there’s a warmth to him that I’ve never seen anywhere else. I suspect it has something to do with him using his real accent.) It’s funny and even a little touching, the way leaders would keep a culture going for the next generation, and it’s followed with another funny little moment: watch as Quinn leads all the children in prayer, there’s one who’s not following at all. That’s exactly what would happen.

Escape from New York gets a lot of its humor from the aforementioned clash of masculinities; in particular, Borgnine’s Cabbie seems to have been completely unaffected by Manhattan getting sealed off, he’s still doing a job. (Perhaps he’s the anti-Travis Bickle.) The running gag in this film has everyone greeting Snake with the same line: “I heard you were dead,” which allows for a lot of deadpan reactions by Russell, allows Isaac Hayes to say that in his subwoofer voice, and also makes complete sense, because it’s not like this place gets updates on an RSS feed or anything.

Sentimentality in action movies needs to be done quickly and once, and both these films hold to that. Spend too much time on those moments and we’ll recognize we’re being manipulated; emotion works under the suspension of disbelief as much as anything else. Maybe the best example in all of action movies is Vazquez and Gorman locking hands on a grenade in Aliens, a moment that has more genuine emotion than James Cameron generated in all of Titanic. Reign of Fire has a scene of children screaming after the castle gets attacked, and Bale breaking down as tries to talk to them; it’s carried entirely on the impact of what we’ve just seen and the strength of Bale’s performance. Escape from New York has a single, wordless look from Maggie on the bridge, saying everything it needs to about her love for Brain. (Adrienne Barbeau makes Maggie as iconic as any of the men in this moment.) Good action filmmaking has an honesty to it, and a level of trust in the audience–it’s not unemotional, it assumes that we will feel the emotions without prompting.

To their immense credit, Escape from New York and Reign of Fire are not ironic. They don’t distance the audience because that’s not how action films, or for that matter any storytelling works. Storytelling works by closing the distance between the audience and the characters. Criticism works on the distance between critic and character, and too many works these days are created for a measured, critical, ironic response rather than audience involvement. (To take just one example, the website for SyFy’s Helix basically says “we know none of you take this seriously.”) The pleasure of this kind of critical stance is that it allows the viewer to feel smart. I’ll take empathy with the characters and a great story over confirmation of my intelligence every time, though, and Carpenter and Bowman deliver a great story, involve me with the characters, and make me feel the intensity of the situation. That’s what great movies do.