Last year, we saw some of the funnybook masterpieces John Stanley created in 1962 — Thirteen Going on Eighteen, Around the Block with Dunc and Loo, and the rest. By 1965, only Thirteen was left standing, and Stanley created a new series: Melvin Monster. At first glance, anything where the characters have silly names like Melvin Monster and his parents, Mummy and Baddy (Geddit? Geddit?) seems like one of the hackiest trendchasers in the minigenre of “kooky spooky” comedies like The Munsters, The Addams Family, or Scooby Doo. But under the surface lurk the much more potent horrors of child abuse and neglect.

I don’t want to jump to the conclusion that Stanley set out to create anything dark or subversive. At the time, all kind of subjects that are taboo today were considered easy comedy fodder, even for the very youngest audience — stuff like suicide, Nazism, and alcoholism is all over the work of Stanley’s contemporaries. The foundations of children’s literature in stories like Cinderella or Hansel and Gretel are all about child abuse. And our definition of child abuse itself has changed radically since 1965, when physical beatings were just beginning to fall out of favor as a discipline technique.

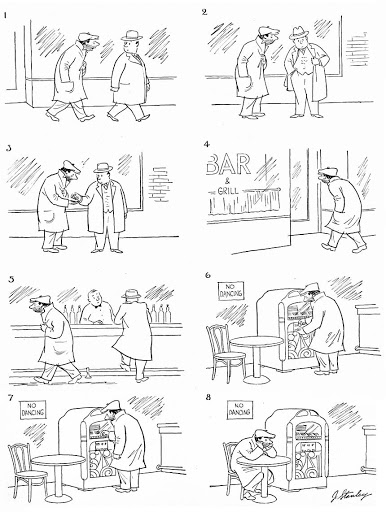

But digging deeper into Melvin Monster, it seems like Stanley knew exactly what he was doing, and if he didn’t, he still fell ass-backwards into a potent and poignant story. (I’m leaning towards option number one — as his lone New Yorker cartoon shows, Stanley knew his way around understated sadness.)

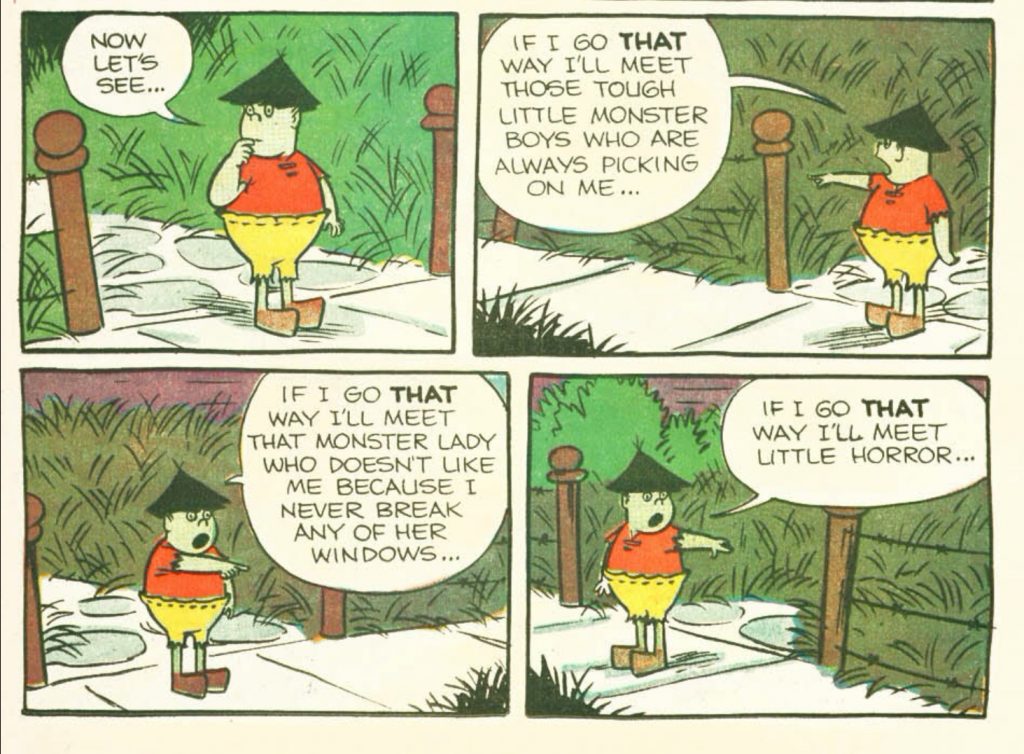

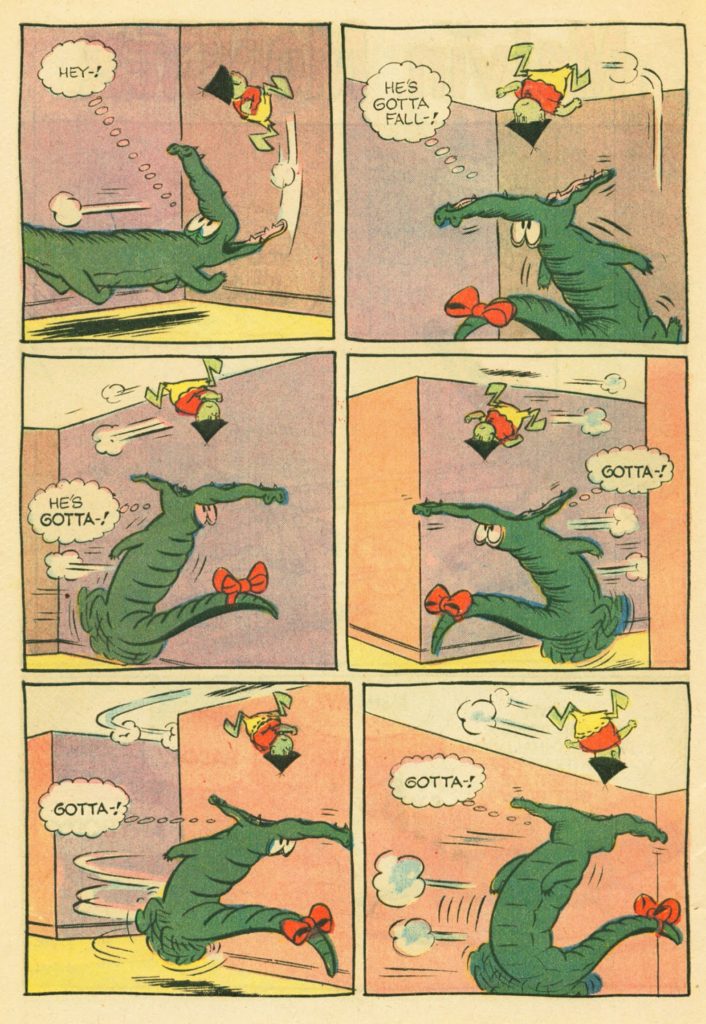

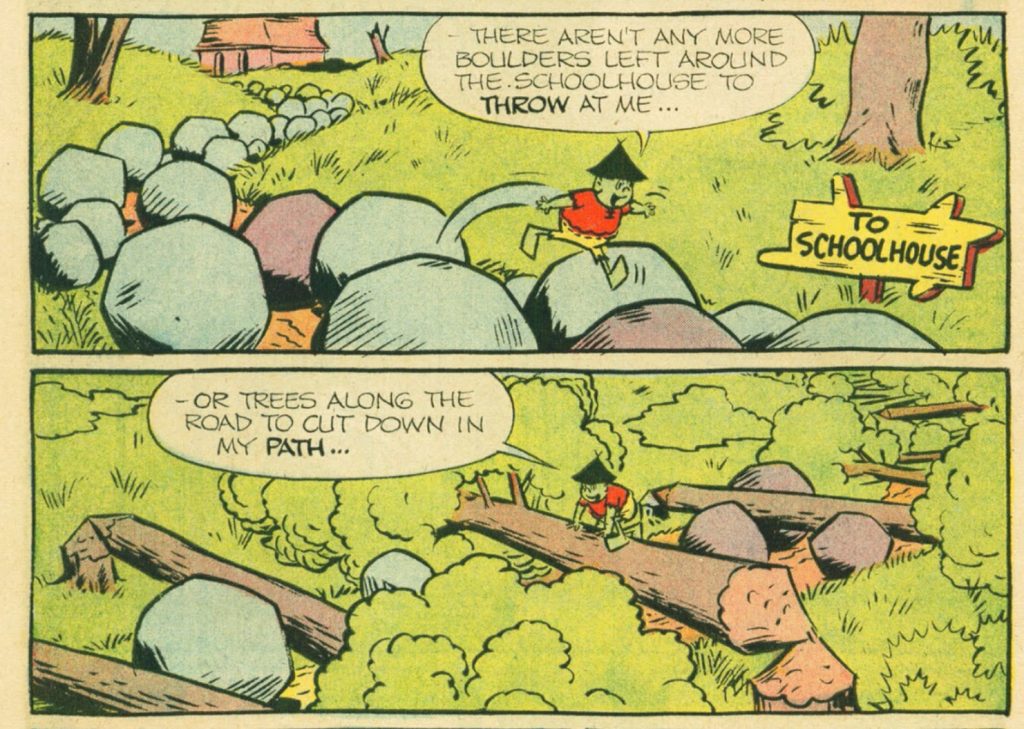

Melvin’s life is a true horror story, not because of any of the toothless monstrosities inhabiting Monsterville but because of the everyday horror of a child trapped in a hostile world. Even the family pet, a crocodile named Cleopatra, wants to eat him alive. He stands paralyzed outside his house for most of a page because there’s danger no matter what direction he walks in.

Melvin’s life is a true horror story, not because of any of the toothless monstrosities inhabiting Monsterville but because of the everyday horror of a child trapped in a hostile world. Even the family pet, a crocodile named Cleopatra, wants to eat him alive. He stands paralyzed outside his house for most of a page because there’s danger no matter what direction he walks in.

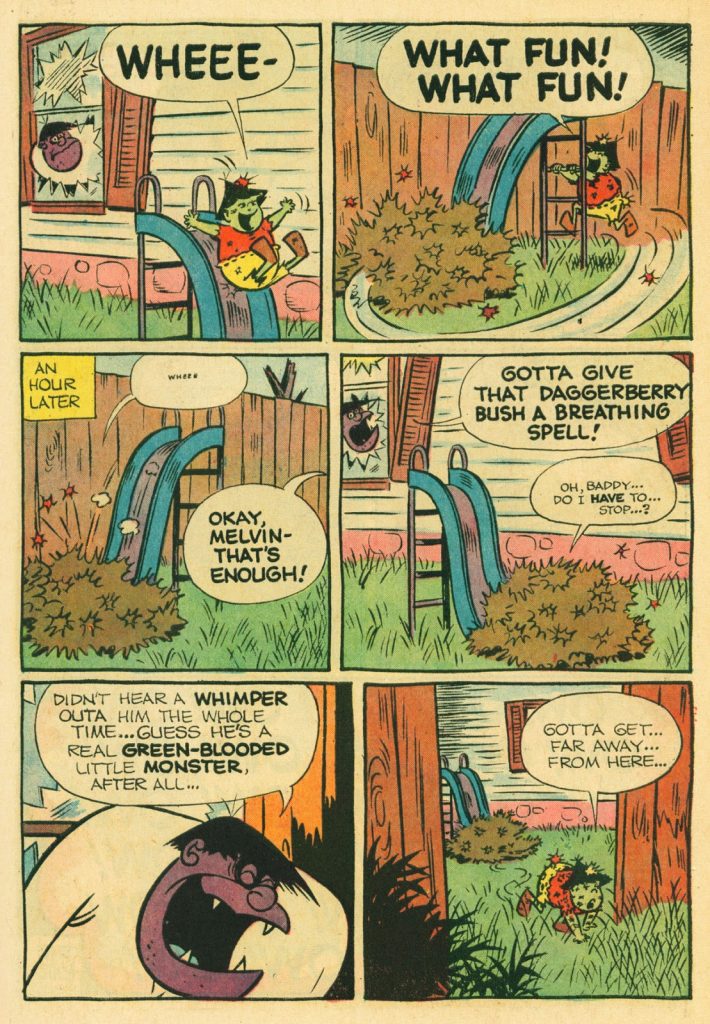

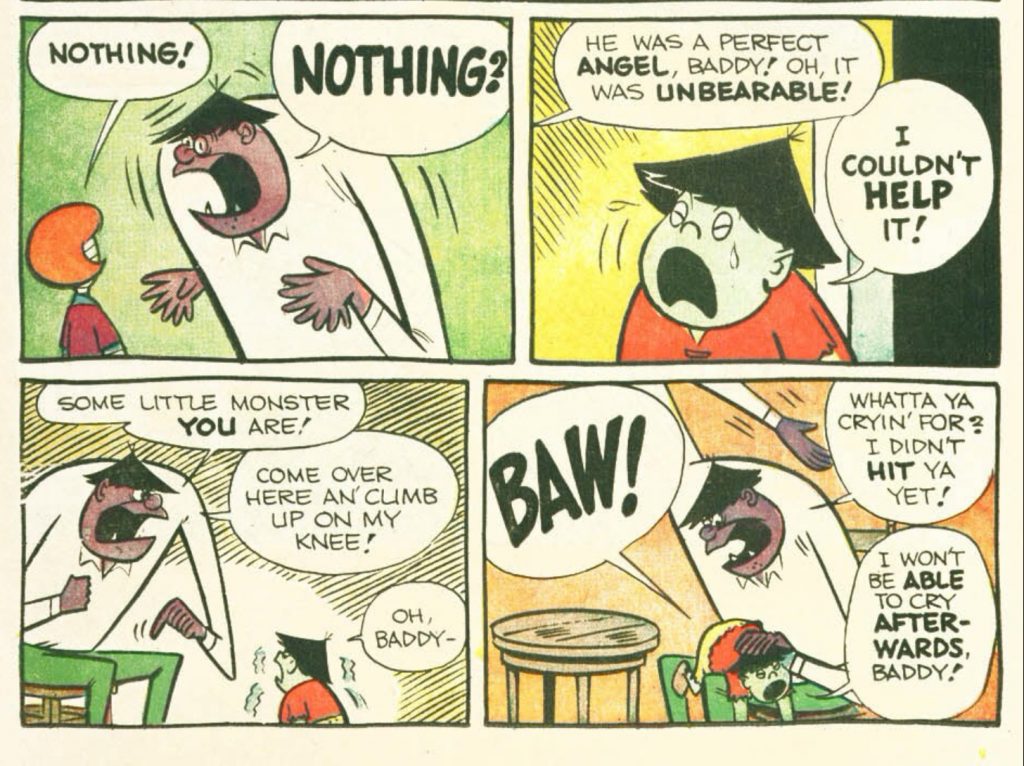

Melvin’s Baddy is a classic macho bad dad, always demanding Melvin prove himself a real little monster. Melvin’s obviously terrified of him, as one hilarious but harrowing little story proves:

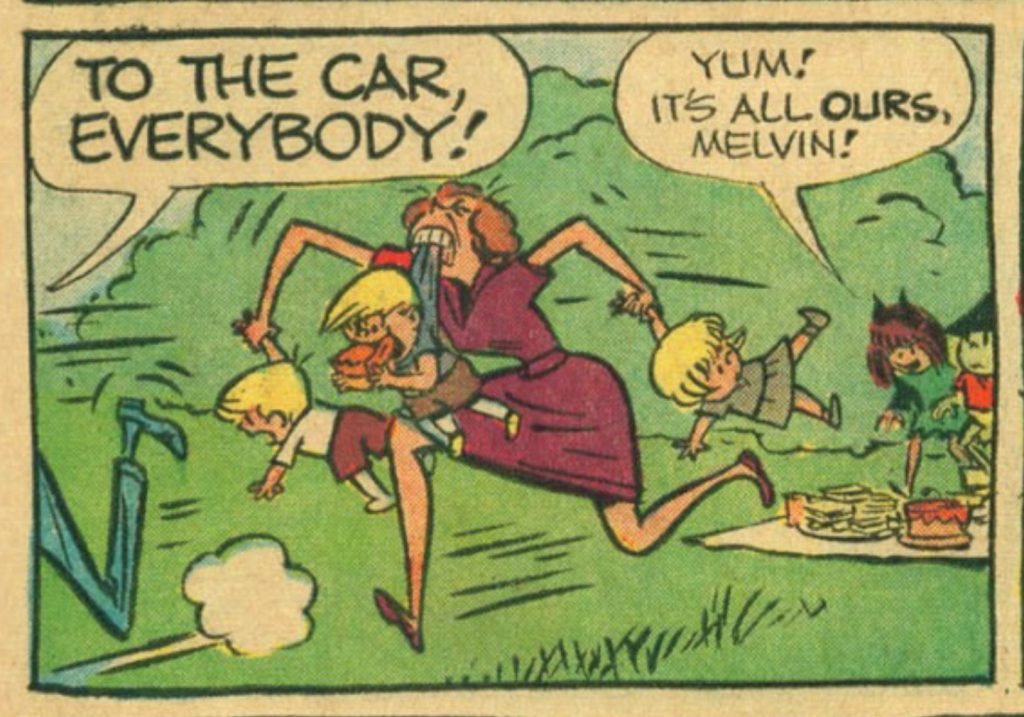

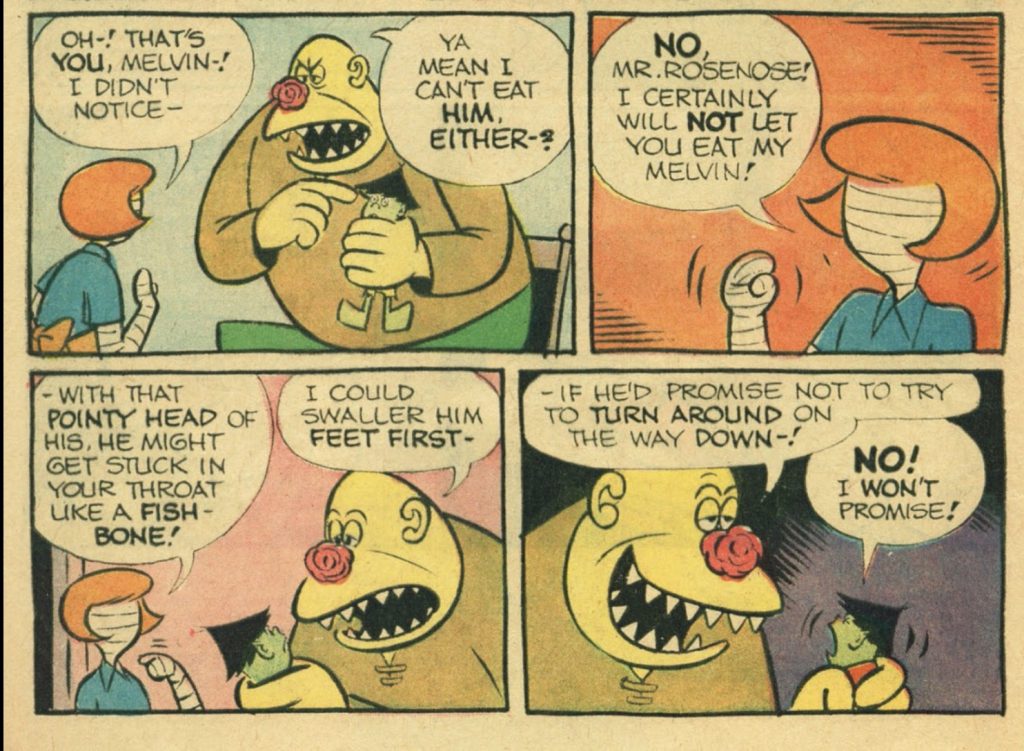

Mummy seems to get off easier. She doesn’t seem to be any fonder of Baddy than Melvin is, as we see in one story where Melvin accidentally shrinks Baddy and Mummy starts whacking him with a broom. After Melvin explains he’s not a mouse, Mummy says, “I know, but when am I ever going to get this chance again?” But if Baddy represents the “abuse” side of the coin, Mummy represents neglect.

For the most part, Stanley keeps the darker implication below the surface, couching it in humor that reveals the true horror if you look at it from the right angle.

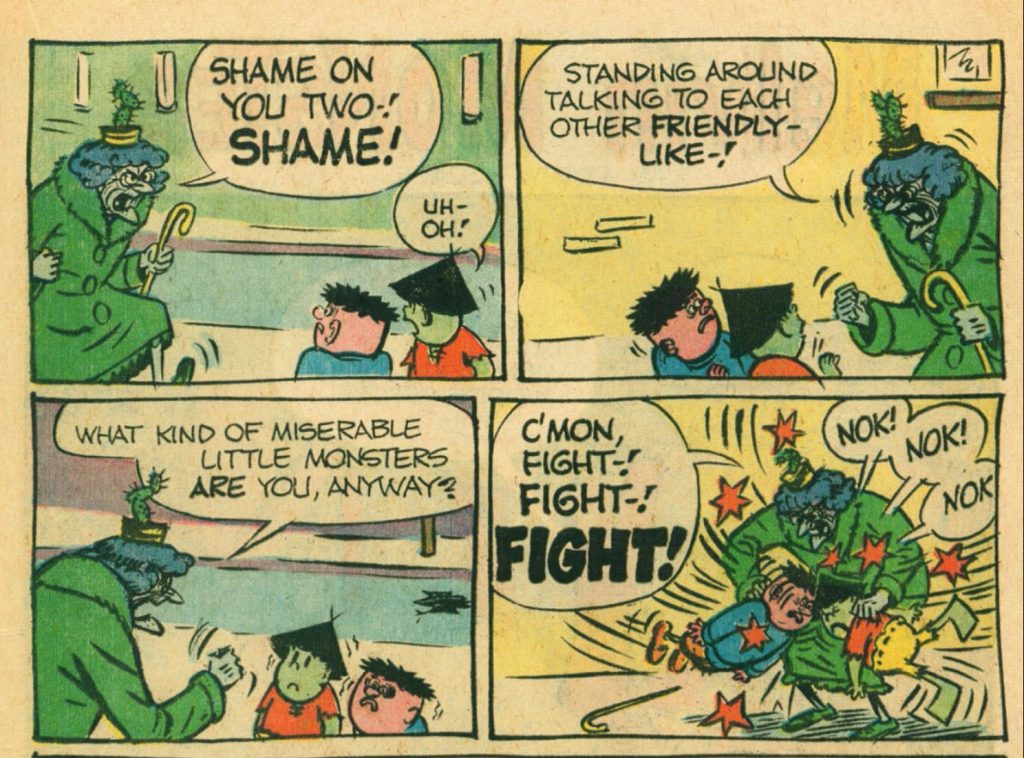

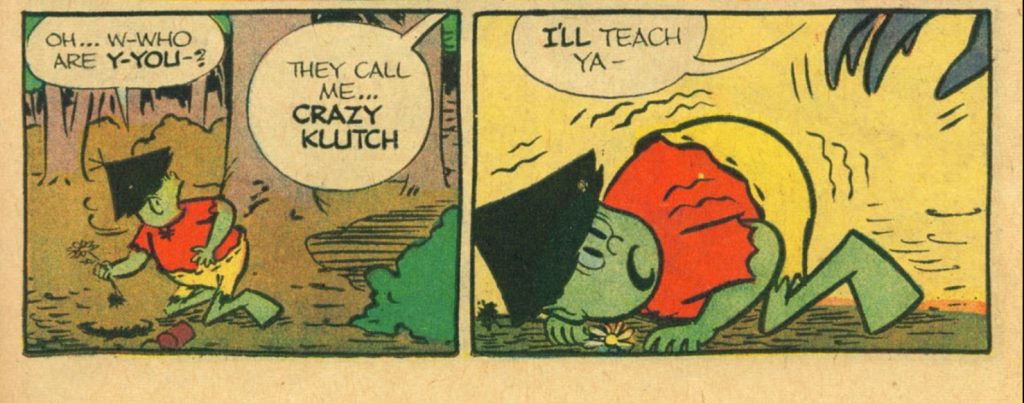

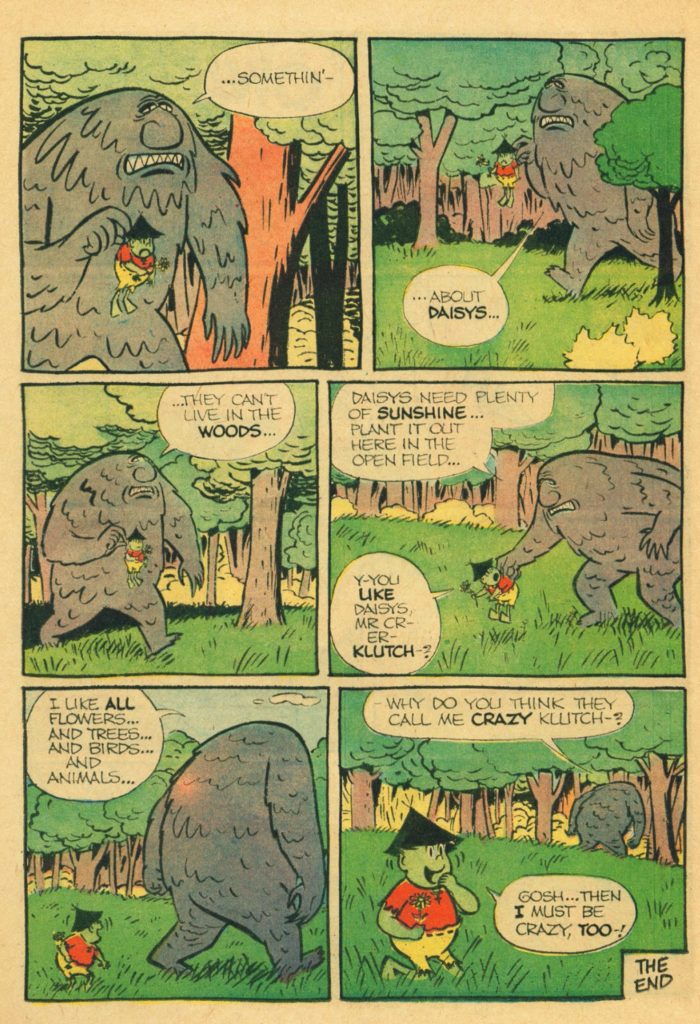

Melvin Monster is right in step with the nonconformist sixties — its hero is trapped in an upside-down world where good is bad, bad is good, and he doesn’t fit in. It’s hard not to imagine some buddingly queer young readers were able to see themselves in these stories, especially when some of Melvin’s “human” habits include picking flowers and keeping neat. In one memorable story, he finds a kindred spirit after being tormented for four pages by stories of Crazy Klutch, a kind of boogeyman for boogeymen.

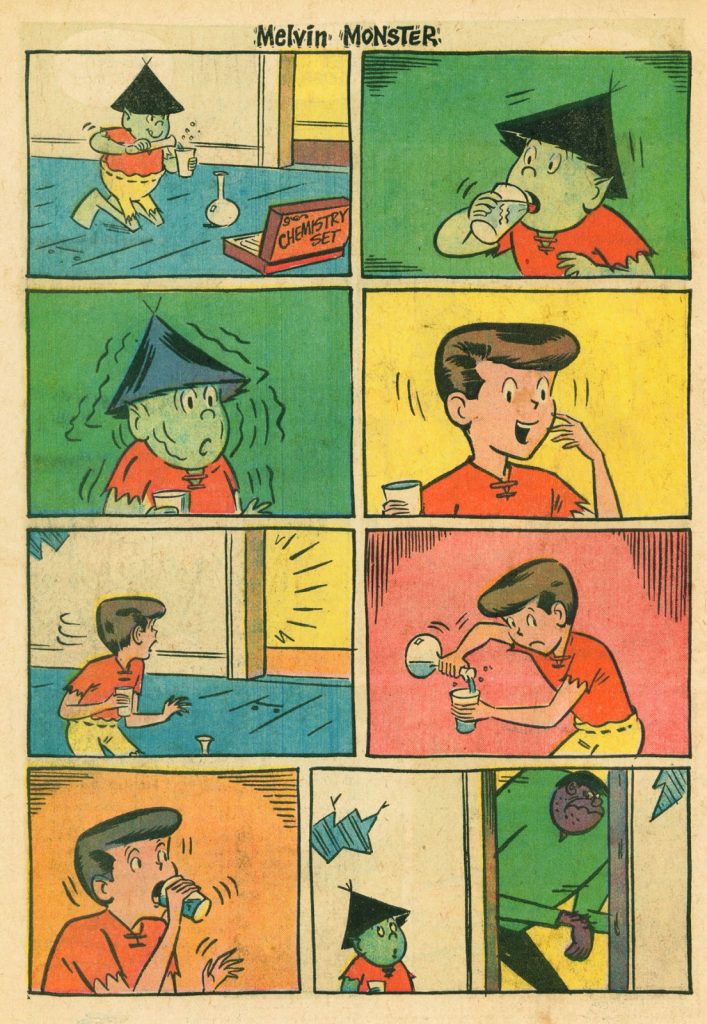

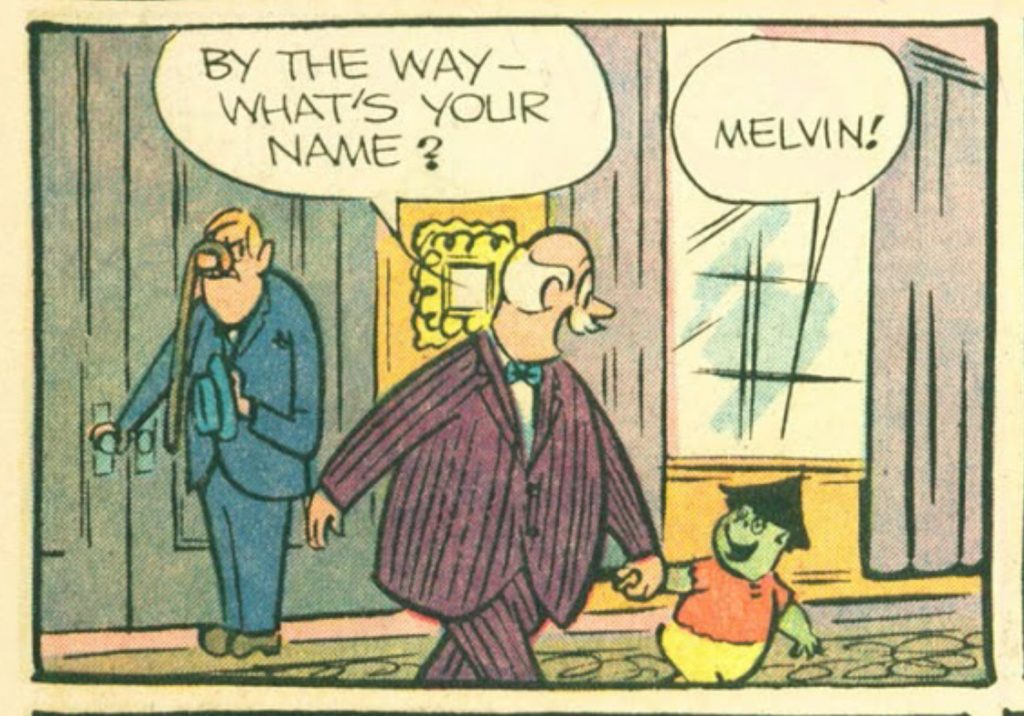

The series ends with Stanley’s take on a classic Mad Magazine gag by Don Martin. It doesn’t really work as a joke since we already know Melvin’s a monster at the beginning. But as a summation of the series and Melvin’s plight as a misfit, it works beautifully.

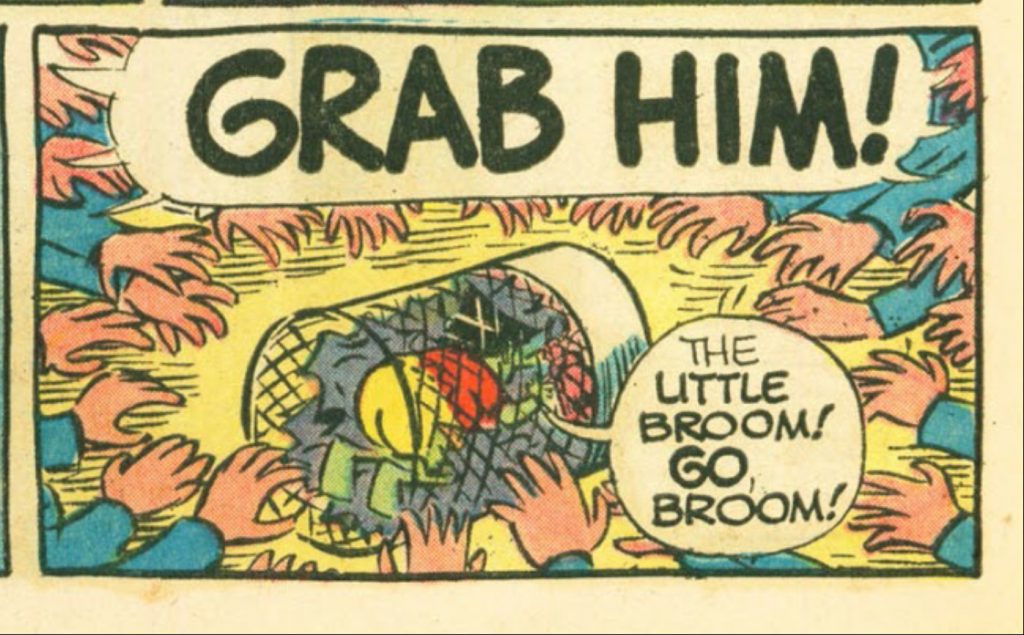

With that in mind, you’d think Melvin’s occasional trips to “Humanbeansville” would offer some glimmer of hope. But Stanley slams that door in his face too. He’s too human for the monsters and too monstrous for the “human beans.” He doesn’t understand our customs any better than his own — he tries to eat a man’s shoe and a cop’s nightstick, and another cop yells at him for climbing in a little sidewalk tree. And the human beans are constantly trying to capture this exotic little creature. The most horrific image in the series isn’t a monster, it’s a mob of humans mobbing Stanley’s hero, drawn as a mass of disembodied hands.

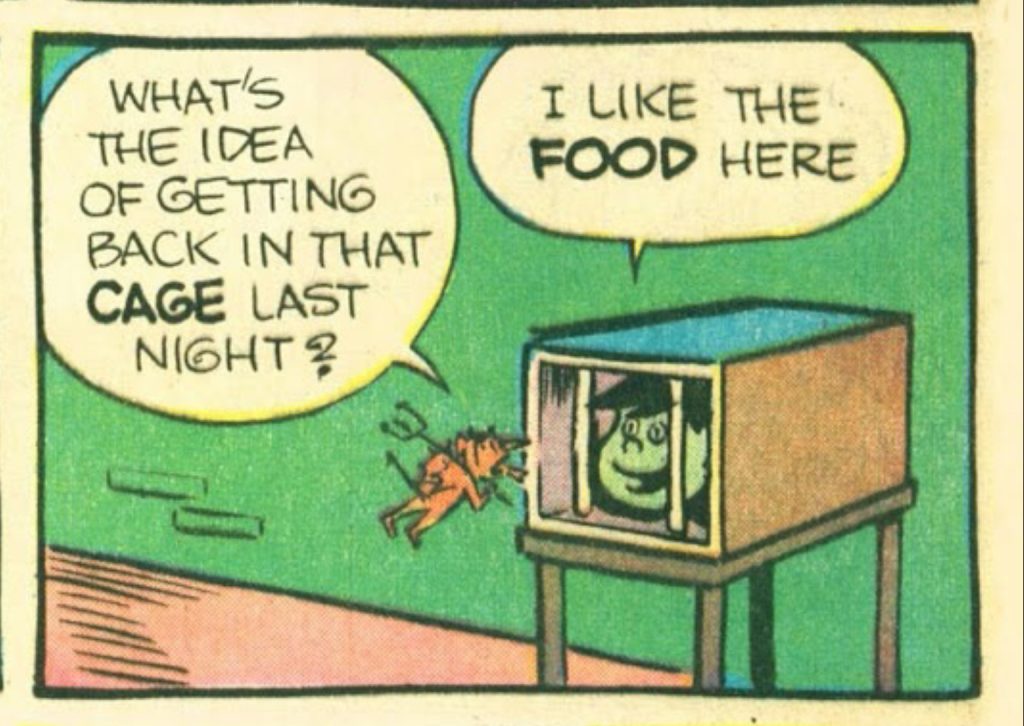

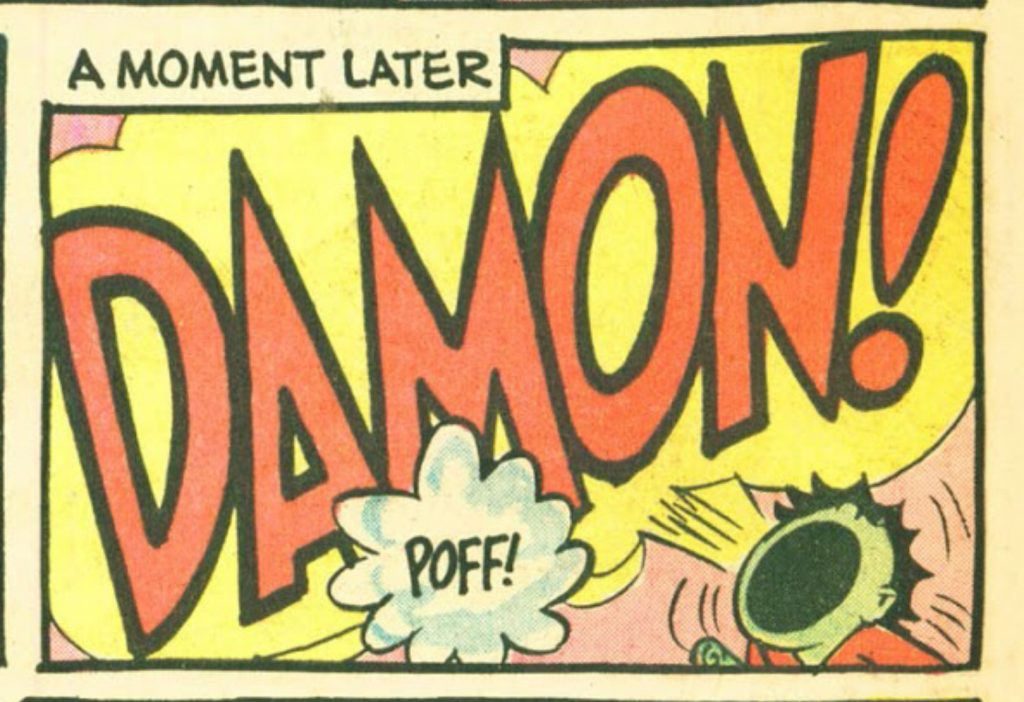

There’s not even a supernatural exit for poor little Melvin. The first issue introduces Melvin’s guardian angel — or, since he’s a monster, his guardian demon (named Damon). But Damon’s interference only makes things worse, when he’s not making bureaucratic excuses to do nothing at all. Melvin spends all of one story trying to get rid of him. If even divine intervention can’t help little Melvin out, where can he turn?

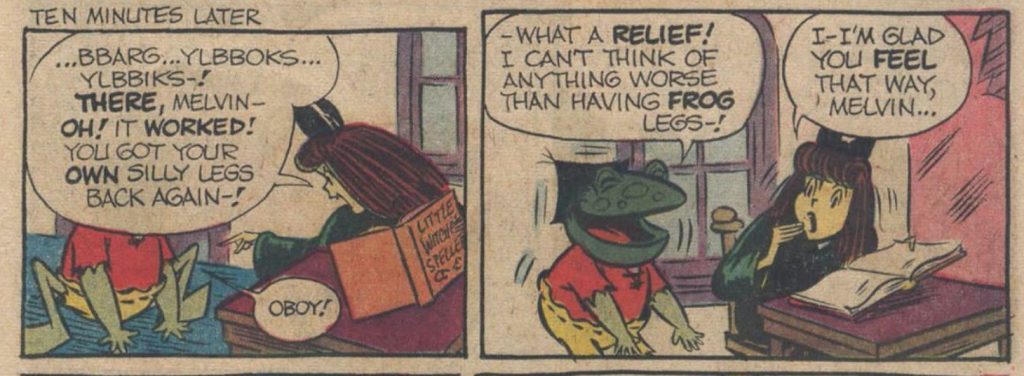

That’s not totally true, of course. There is a benevolent deity in Melvin Monster, and his name is John Stanley. As much as he’s set up Melvin for suffering in the macro, Stanley moves heaven and earth to help him out in the micro. There’s a lot of slapstick suffering in Melvin Monster, but Melvin himself is the butt of relatively little of it, especially as the series goes on. More often, the brunt of Stanley’s abusive comedy falls on Melvin’s tormentors, usually as a direct result of the ways they try to torment him. Baddy, especially, takes almost Wile E. Coyote levels of karmic punishment and humiliation. There’s probably no better example than the story where he gets shrunk:

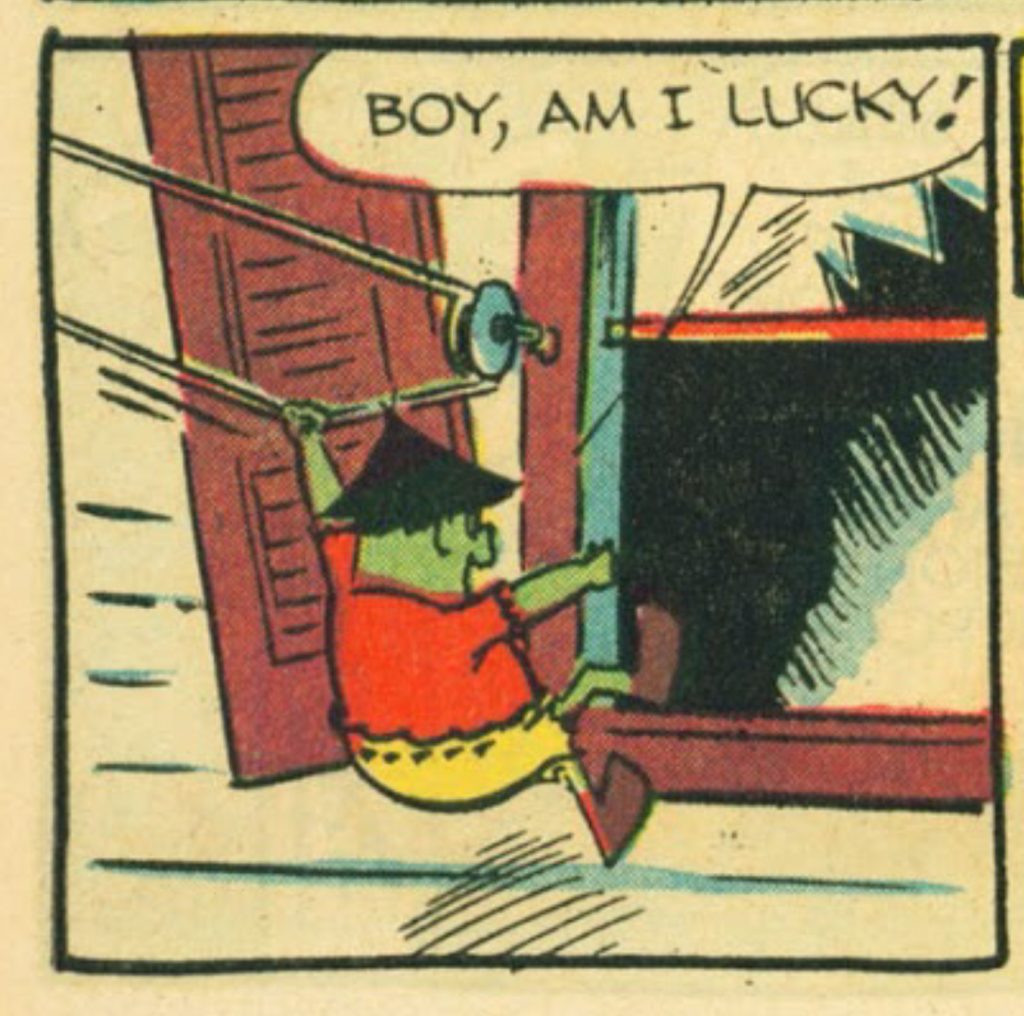

Every once in a while, Stanley rewrites the laws of physics themselves to keep Melvin out of danger.

That’s one factor that makes Melvin Monster a hilarious comedy instead of a miserablist slog. Number-one John Stanley fan Frank M. Young disagrees. A sensitive soul, he’s able to find the “interplay of dark and light” and “theater of cruelty” in Stanley’s frothy kiddie comics, so naturally he finds Stanley’s sojourn into real darkness too much to take, and he’s said on his essential site Stanley Stories that he avoided it for years.

In my view, though, Melvin hits that balance much better than Stanley’s other work, which is almost all light with very little dark. Part of what makes it so fascinating is the gulf between content and presentation. You could read all nine issues (Melvin ran for ten, but the last issue is a reprint of the first) without ever realizing just how dark it is, and you’d still probably have a great time. It’s only when you peek under the surface that you see how thematically rich it is.

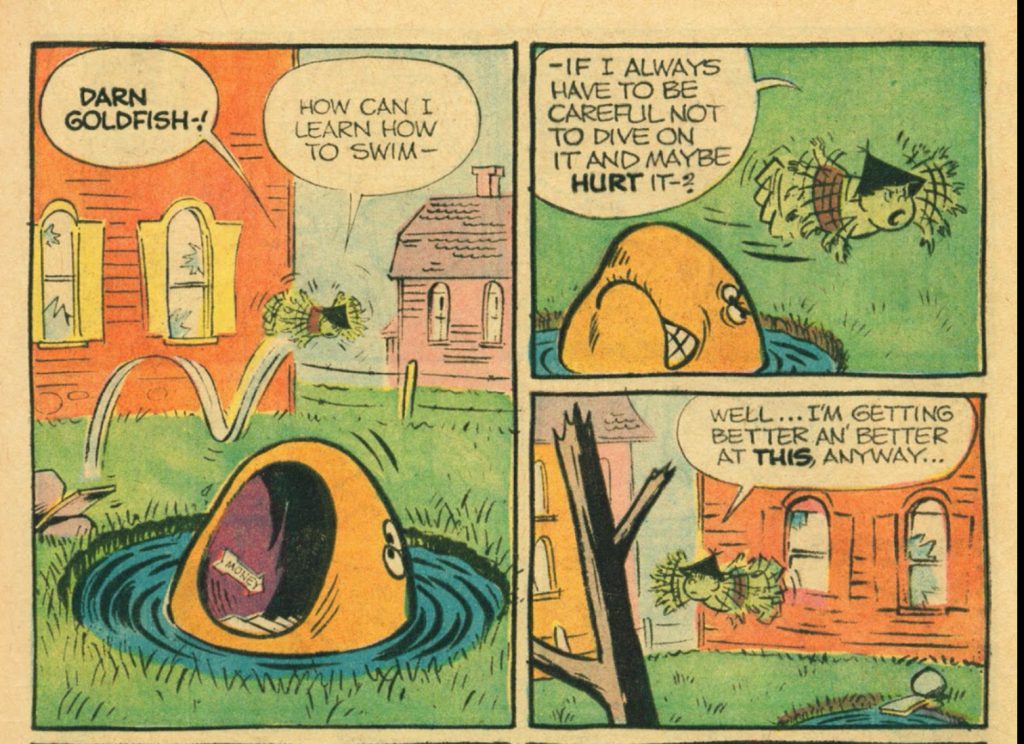

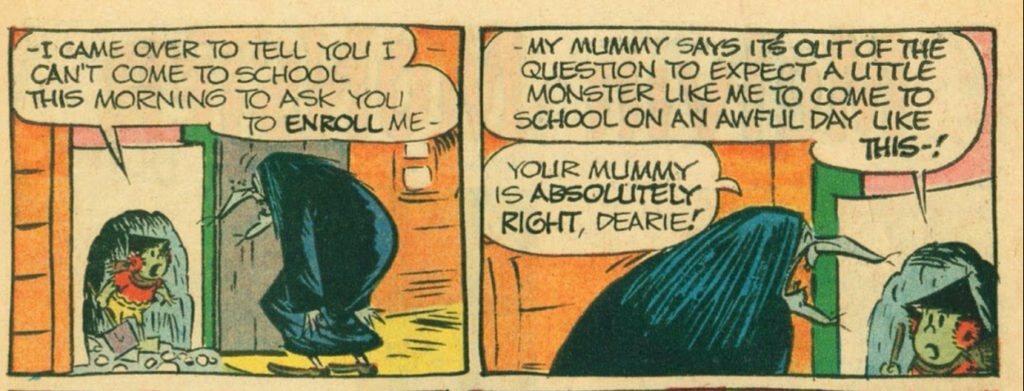

Stanley has several tricks up his sleeve to keep that balance. The most winning is Melvin’s personality, maybe the most vivid he ever created. Melvin is seen openly weeping way more than your average comic book hero, but for the most part, he reacts to the unrelenting horror of his daily life with charmingly cheerful obliviousness. This is especially true in his ongoing battle with Miss McGargoyle, who runs the “little black schoolhouse” where Melvin wants to enroll even though monsters are supposed to play hooky. (Why the schoolhouse even exists is anyone’s guess.)

Every once in a while, that crosses the line into cheerful sociopathy, when Stanley hints Melvin knows exactly how much damage he’s doing to his adversaries.

Even when Melvin does get the short end of the slapstick shtick, he doesn’t react with much more than mild confusion, in Stanley’s classic deadpan style.

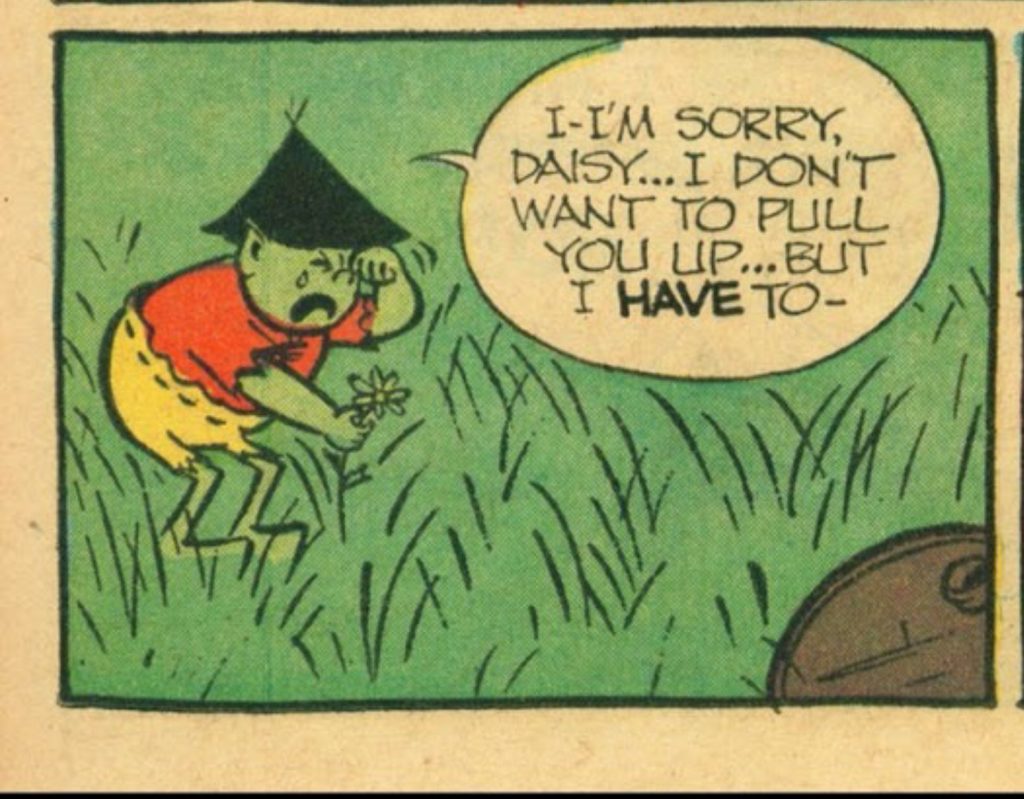

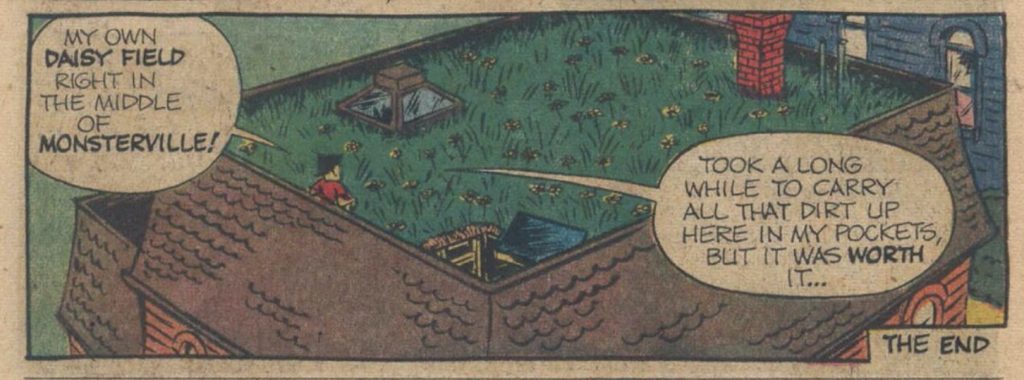

The threat of parental violence is always there, but always kept safely in the background. Even in 1965, actually seeing Baddy beating Melvin would upset the comics’ delicate balance, and Stanley knows it — even in the scene above, Baddy’s interrupted before his hand can fall on Melvin’s ass. And sometimes, Melvin wins a little victory over the cruelty of Monsterville, like the conclusion to this story, not with a punchline but a surprisingly bittersweet little moment.

The closest thing to the punchline is the deadpan absurdity of Melvin offhandedly describing carrying a garden’s worth of dirt to the roof in his pockets. That’s one of Stanley’s trademark skills, and it’s alive and well in Melvin Monster:

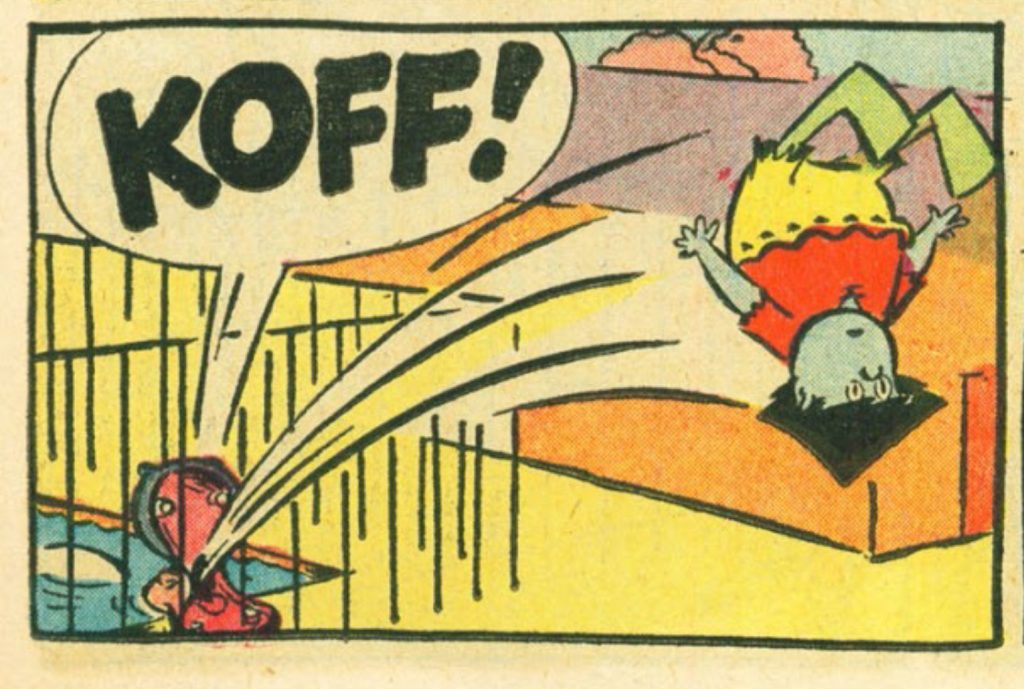

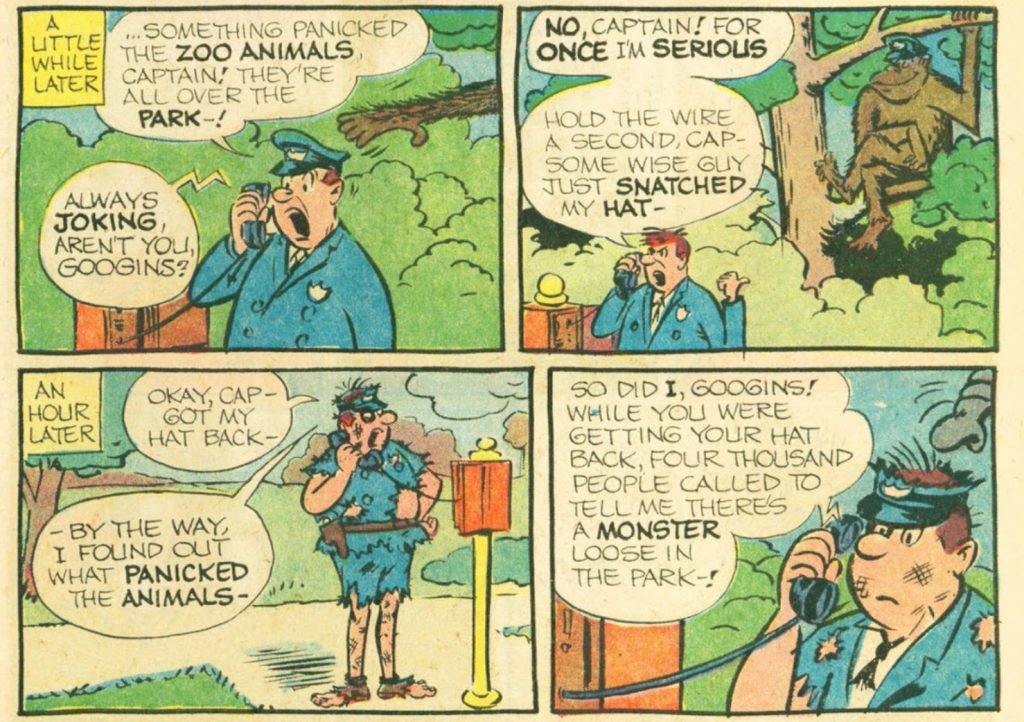

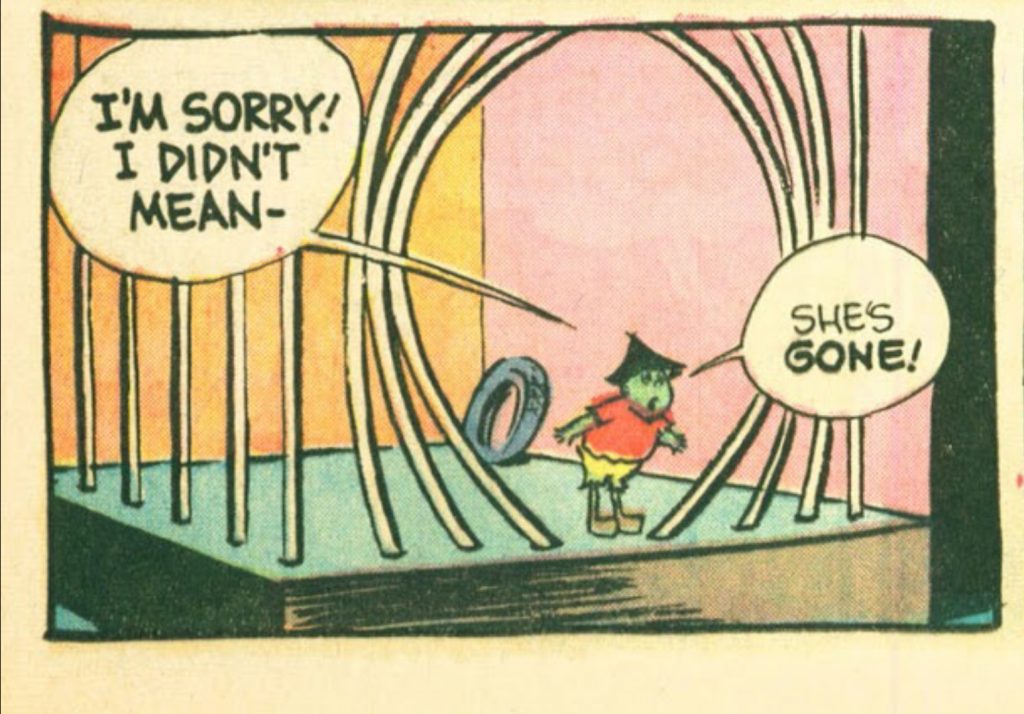

So’s his love of implied chaos, putting the cartooniest moments into the gutter between panels.

Melvin Monster shows an artist in total control of his craft. Check out how Stanley uses the building blocks of his medium to carefully withhold a necessary revelation until just the right moment.

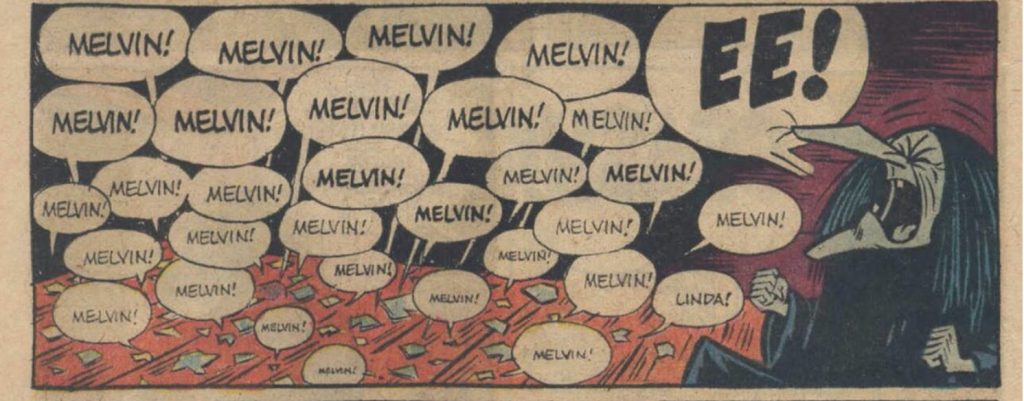

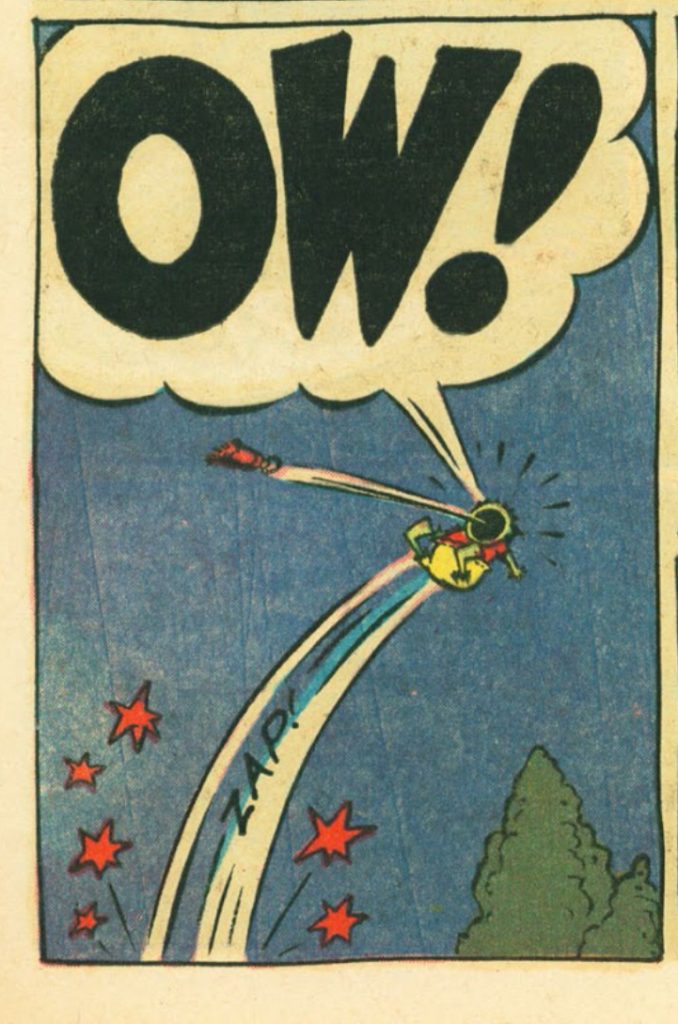

Few of those building blocks are more underappreciated than lettering, but Stanley makes the words stars in their own right, from abstract word-collages

to bold use of block letters.

It’s probably inevitable that such a dark, idiosyncratic little series was never going to last. But Stanley’s nine issues are still worth unearthing for the melancholy magic he conjures up within them.