In which Avathoir and wallflower take a break from discussing Thomas Pynchon’s writing to talk about a movie that Pynchon has never denied he made. . .

That just raises further questions! (Futurama)

wallflower: It’s been a third of a century since The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai: Across the 8th Dimension (written by Earl Mac Rauch, directed by W. D. Richter, with a cast of several) was released and I saw it, and there has been nothing like it, since or before. I define a “perfect movie” as “one in which every element contributes towards the whole, where every element is necessary and can’t be changed without damaging that whole.” That describes Buckaroo Banzai but there’s no way I can call this movie perfect, since its defining characteristic is a joyful messiness. Every element contributes here and everything is necessary and for no reason I could ever explain to you. It’s a glorious work of “tonal anarchy” (to steal a phrase from Pynchon, not for the first or the last time here) that, like its eponymous hero, goes “in several directions at once.”

That Pynchonian aspect of Buckaroo Banzai goes way past name-checking Yoyodyne Propulsion Systems (“A Growing Excited Company”) Up front: we’re doing this because I’m a longstanding fan (still have my Yoyodyne lab coat, still fits) and Avathoir just saw it last weekend, making this a Blind View movie. Still, long before Inherent Vice, Impolex, and even Test Stand VII (the last two derived from Gravity’s Rainbow), this felt like it was an underground, unofficial Pynchon film. (He might have had a hand in writing the screenplay, and if I’m wrong, he can fucking well get in touch and correct me.) It came out the same year Slow Learner was published and Vineland was set, and Pynchon was rumored to have a Japan-set novel in the works for some years; in any case, to claim that something runs contrary to historical evidence feels pretty silly after reading Pynchon. We’ll get to all the crazy brilliant joyful aspects of Buckaroo Banzai soon enough, but let’s take this one on first: how do we know that this is a secret Pynchon film?

Avathoir: Oh gosh, where to begin? The ridiculous names? The plot which gradually becomes even more surreal than the opening title crawl implies? It’s hard to know where to begin, but if I had to say this is a secret Pynchon film based on one particular quality: the utter mundanity of its absurd premise.

Now, let me elaborate a bit on that idea: There’s a very big difference between what this movie does and something like Airplane!, Pynchonian as both may be. ZAZ are outright making comedies in their golden era, merely exploiting the classic premise of something absurd being taken completely seriously. The last word is key: ZAZ at their best knew they were funny and were thus working in a comedic register.

This is not that: mundanity implies a sense of ordinariness, which is what this film is doing far more. It’s a funny movie, don’t get me wrong, but the entire premise of it is presented as utterly ordinary, or as ordinary as material like this can be taken. What else could you use to describe a movie whose lead is a brain surgeon, an experimental physicist, a rock and roll star, whose parents named him Buckaroo Banzai, and not only doesn’t bother to wink, but isn’t interested in making us laugh.

Which of course makes it a Pynchon work: a lot of Pynchon is funny, but he’s treating everything like its par the course, which makes it something that is sometimes MORE funny then if he had acknowledged the humor of the situation (imagine sitting through several hundred goddamn pages and then encountering the Burgher King). This unique approach I think is the gene Buckaroo Banzai shares with Pynchonland: the mundane absurdity. Which is kind of why the movie frustrated me, since it meant I didn’t know how to feel at certain points. There’s such a thing as being TOO pokerfaced.

Your move wallflower. Have I hit the nail on the head? Or is there something I’m not picking up on or…?

wallflower: “It is this way with sewer stories. They just are. Truth or falsity doesn’t apply” (V.)

Avathoir: Don’t you dare pull any of that zen koan shit right here. The people came to READ.

wallflower: As I was going to say before a certain someone decided to come crashing the party, you’re onto something here. There’s something about comedy that’s communal, especially when an audience is around. What Buckaroo Banzai has in common with Airplane! (or better yet, Top Secret!) is its thoroughness, of which more shortly. Where it differs, though, is that ZAZ films are clearly comedies, jam-packed with jokes all the way to the end of the end credits: they give you permission to laugh. Buckaroo Banzai, although it’s funny all the way through, doesn’t play as a comedy, rather as a fairly tight science-fiction thriller. It never cracks a smile.

Reading Pynchon, really reading any great author, I don’t get the sense that he’s trying to make me laugh–or cry, or think he’s smart, or anything like that; I feel that this is just how he sees the world and he’s trying to communicate that to us. That’s what Buckaroo Banzai feels like, too: a complete world of its own that was lurking inside 80s action movies and Silver Age comics until this movie crossed the dimensional barrier and brought it out. (Referential metaphor. BOOM!) It’s complete unto itself, and why should it care if we laugh at it, or even get it? Even a work like Hot Fuzz, which loves and parodies its genre equally, wants to get reactions from us (and oh my yes it does) but Buckaroo Banzai doesn’t.

That does make one’s initial reaction to it tricky, but that’s also why it lasts. (Well, that’s one reason. More will follow.) Back at The Dissolve, Noel Murray said that it feels like “part of a larger, more vivid cinematic universe.” Just the fact that there’s a subtitle here and an ending promise of another film (Buckaroo Banzai Against the World Crime League is one of the all-time great never-made movies; I believe that legendary commenter Cookie Monster has written a script) places this as part of a larger world. Even more effective is the sheer density of everything on display here: characters, settings, dialogue, everything feels like it comes with its own backstory, everything feels like it could have an encyclopedic Pynchonian explanation. (The commentary tracks on the DVD release, which treat the movie as a docudrama, provide quite a few explanations.) The most famous example is the answer to “why is there a watermelon there?”–the Banzai Institute was developing a strain of watermelons with tough rinds so they could be airdropped into hunger-stricken places. You could imagine origin stories for every character (I’ve always wondered why Pecos is in Tibet); in forms of storytelling, Buckaroo Banzai fits squarely in the mythological mode, a Doctor Who where we come in at a later season–and sadly, that’s the only one we got.

Let’s dive a little further into those details. What are you noticing about this? What was funny and what didn’t work? And of course, what are your current favorite quotes?

Avathoir: A list of everything that works perfectly in Buckaroo Banzai, in rough order of best to worst:

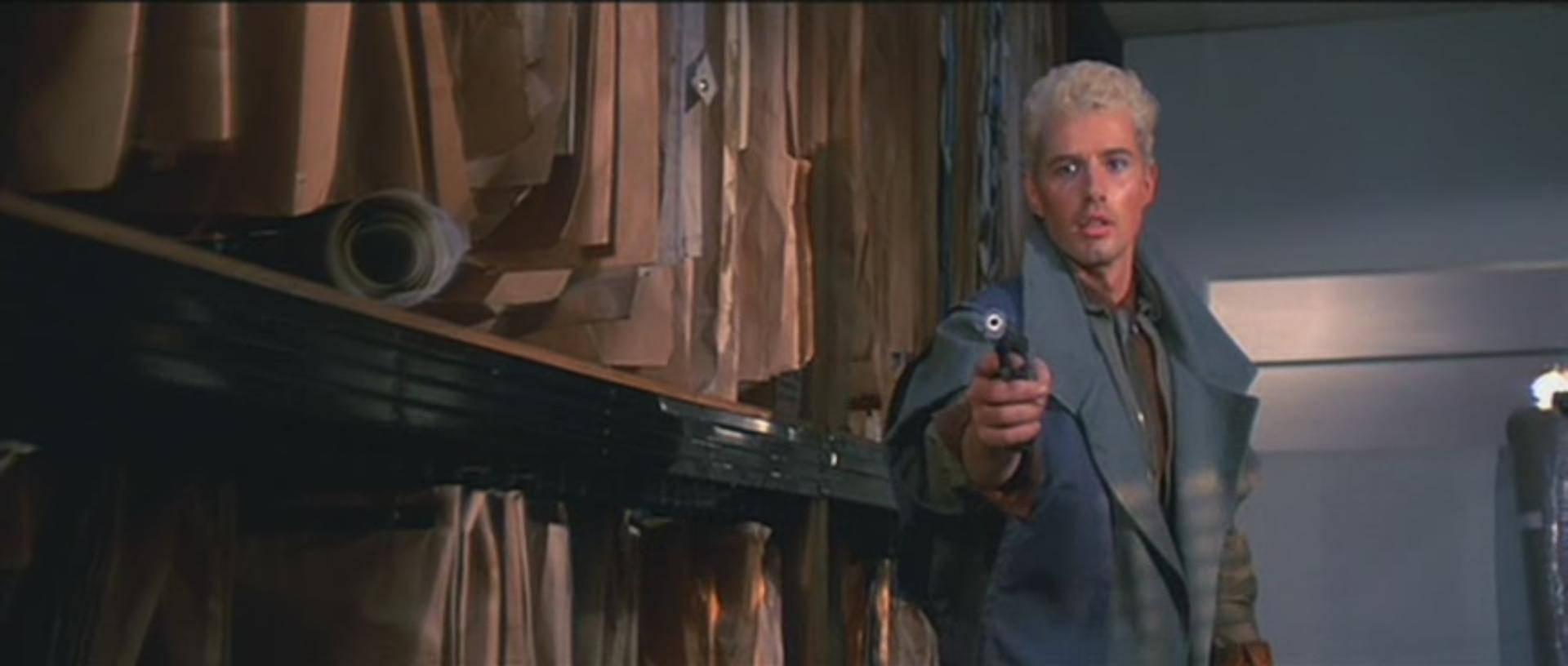

The one musical performance. As I said before, this is when the movie fires on all cylinders for me, and is the most Pynchon-esque: there’s the fact the song is already good, there’s the Streets of Fire-style lighting (speaking of which we should do THAT sometime as a Conversation) the fact that it gets interrupted when Buckaroo notices the ONE person there not utterly enraptured, when he tries to serenade her while his bandmates comment on how weird that is, and then the accidental assassination attempt. It’s all brilliant stuff, though I think Penny Priddy (Ellen Barkin) kind of goes on a little TOO long with her crying but that’s 100 percent part of the joke.

Priddy’s actually best scene, in which she has an entire conversation with Buckaroo off screen thinking she’s going insane. It’s a mundane choice perhaps, but the soap opera quality of the whole thing just works brilliantly.

Lithgow’s introduction. It’s such a great supervillain entrance (the ridiculous accent, the over the top insults, the mispronouncing of names) that its retroactively spoiled by revealing he’s been possessed by the leader of the aliens. It’s like revealing Doctor Doom actually was good and just happened to be possessed: it’s a nice twist, but why complicate something you got right the first time?

Lithgow’s introduction. It’s such a great supervillain entrance (the ridiculous accent, the over the top insults, the mispronouncing of names) that its retroactively spoiled by revealing he’s been possessed by the leader of the aliens. It’s like revealing Doctor Doom actually was good and just happened to be possessed: it’s a nice twist, but why complicate something you got right the first time?

The ending credits, which are so perfect that I am actually kind of mad they didn’t open the movie, setting up the tone. It’s amazing how just a group of people walking can feel so right. [wallflower‘s note: I believe Wes Anderson flat-out stole that for the end of The Life Aquatic. Good on him.]

That being said, I’m glad you mentioned Edgar Wright, because as much as I love a lot of his work, I see the same problem with him that I see in this particular venture: the dissolve into noise. At a certain point, the masterful Rube Goldberg devices explodes, and as much as I enjoy the aliens coming to earth and Buckaroo staging a raid against them, it’s so non thrilling that I have to admit I found the whole thing noisy and kind of overlong. I imagine this is a downside to not seeing it on a big screen.

Really, this is sort of the same problem I have with Pynchon: when you’re juggling a lot, eventually, somewhere, you start to drop things. As precise as this movie is, when it hits the halfway mark something goes wrong in a way that makes it waver from the enormous highs it was already hitting.

As for quotes, I’ll be saying the “no it’s not obvious, if it was obvious people would be doing it all the time….” all the time. I may or may not call you a monkey boy. It’ll take a while to decide.

wallflower: Oh I’m sure in the miserable annals of the Earrrrth, you will be duly enshrined, Avathoir. Let’s run a little further with the Edgar Wright thing: his movies are so-well constructed, with everything set up in the first act paying off by the end, often spectacularly and unexpectedly. (He also, agreed, has a much stronger sense of how to stage an action sequence than Richter.) Buckaroo Banzai isn’t as well-constructed, but the thing is, it can’t be. Sprawl and excess come with the aesthetic here. Going back to your comment “why complicate something?” well, that’s what we do here: complicate things until it’s really out of anybody’s control. Wright’s films are good machines; Buckaroo Banzai, again like Pynchon, is part of crazed but complete universe.

One of the reasons I’ve loved that universe from the beginning (and another Pynchon connection): this is a movie that’s not so much science fiction as about science. Not science as it exists in the popular imagination: rational, methodical, neat ‘n’ clean, but as it’s actually practiced, the goofball inspirations (this is the first panel of the Jeff Goldblum Nerd Quartet of the mid-80s; watch him put together the War of the Worlds connection and flub a line), the omnipresent pop culture artifacts, and most of all the messy productivity of lab work. Richard Feynman (I met him, he answered a question I had about particle decay, fuck yes I bring that up at every opportunity, you would too) was at Princeton at the same time as Dr. Emilio Lizardo (HMMMMMM) and described how the Princeton cyclotron was a complete mess, stuff all over the lab, cheap soldering everywhere, and compared that to the nice clean device he saw at MIT. The key difference, of course, was that Princeton was getting results because no one cared what it looked like; if they wanted to do something, they just slapped it together and did it. The Banzai Institute looks exactly like that (look at the duct-taped, um, duct on the wall) and Yoyodyne Propulsion Systems looks like that if no human had inspected it in 50 years. The sound design is just as cluttered, too, with electronic beeps and noises and background announcements (remember, lithium is no longer available on credit) from start to finish. This is a Mirrored Movie to Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control, another work about the messy essence of science that never announces itself as such.

Let’s get back to that mundanity, because a) you’re absolutely right about it and b) it ties into another aspect of the movie that we’ve alluded too but haven’t fully discussed. Part of what distinguishes Buckaroo Banzai is the way Buckaroo, his legend, and the Hong Kong Cavaliers are just an accepted, everyday part of its universe. When a hunter says “Buckaroo Banzai. It’s the latest issue,” it’s in the tone of someone who knows that latest issue and possibly follows the comic. Artie, owner of the nightclub Artie’z Artery, knows Buckaroo went through a mountain “but this is New Jersey” and he expects a good show. (Yeah, that show is fantastic from start to unexpected finish, and in its music and fashions it may be the most 80s thing ever. I’ll go farther than that: Perfect Tommy’s costumes are a kind of architectural wonder, a zoot-suit derived mashup of shoulder pads and paneling. They have to be seen to be disbelieved.) Like the comedy, this all may be surprising to us but it’s just another day to the cast.

That mundanity gives Buckaroo Banzai its deadpan tone, which is an essential component to perhaps its most obvious claim to greatness: this is one of the three most quotable movies in film history, with Dr. Strangelove and The Big Lebowski as the other two. (I couldn’t possibly rank them.) What all three have in common, what makes them the best, is that there are no lines in the movie not worth quoting, because every line has its own unique style and inflection. You can’t quote any of these movies without imitating the speaker, from President Ronald Lacey’s “Jammed? By who? Who by?” (a forerunner of Philip Seymour Hoffman’s “children without the necessary means necessary means for higher education”) to any time someone says “it’s Buckaroo Banzai!” to Matt Clark’s gloriously stupid secretary of defense taking names (“Johhhhhhhn Small Berries!”) to all of Lizardo’s and Buckaroo’s pulptastic lines (“EVIL! PURE AND SIMPLE FROM THE EIGHTH DIMENSION!”) to (current personal favorite) Lewis Smith’s “That is an act that the Kremlin would most certainly misinterpret as a United States first strike!” (Again, it’s all about the delivery–Smith’s tone is “wait wait, I know this one!”) Like Strangelove and Lebowski, you don’t get it all at first: all three films are off-center enough that the first trip through provokes more puzzlement than anything else. Once you get on their wavelength, though, you’ll laugh yourself stupid through all three and be repeating the lines decades later. Like I do.

Avathoir: See you SAY this but I worry that I don’t believe you. Strangelove and Lebowski are movies that, though they improve on repeat viewings, I did “get” on the first go through. The former has Sellers and the latter has “This is what happens when you fuck a stranger in the ass” for the groundlings, but this movie does not give a good goddamn for that sort of accessibility. I may be a monkey boy in admitting I didn’t reaaaaalllly get this one on the first go, and I really would like to try again sooner rather than later.

But then again, this is a movie that will reward multiple meanings, as we’ve both established. As I’ve thought more and more about this movie, the acceptance of it as its own Pynchonian/Altmanian universe is something I’ve come to heavily appreciate, and will perhaps love on future viewings. At the same time, I have to admit that unlike certain Pynchon stuff, movies that embrace this comic book universe (Hello Streets of Fire) I must say I feel no particular emotional connection to these guys at this go round, at least until the ending credits where they walk off to their next adventure, which unexpectedly hit me right in the gut. I’d do a LOT to see the World Crime League battle, and the fact that Kevin Smith wants to make an animated tv show of this feels…wrong. It’s a film whose characters on their own I don’t feel the same attachment to, but who I fiercely cherish when they’re together. Is there a word for that?

wallflower: the word we’re looking for is “team,” especially a superhero team. Maybe that’s what Buckaroo Banzai accomplishes most of all and why it’s endured: it’s another example, in John Bruni’s words, of why the future of comic-book superhero movies is the past, a demonstration of what a superhero team-up looks like when all the energy goes into creating a new team in a new universe and no one gives one fuck about franchising, how to set up the sequel, how to explain everyone’s backstory, or which fast-food operation gets the collectible cups. (Of course, it’s entirely possible that’s exactly what Richter and Rauch were trying to do and they just completely failed.) I still hold that our relations with art are much like our relations with people, especially the relationships that endure, and your best friendships aren’t gonna be the ones where the other party is trying to sell you something or get you to meet all his buddies which, really, you’ll love them they’re all totally cool. Our enduring, rewarding relationships with people and art are with those who are to thine ownselves true. Give it time, Blue Blazer Irregular Avathoir will be reporting for duty soon enough.