All the modern things

Like cars and such

Have always existed

They’ve just been waiting in a mountain

For the right moment

-Bjork

Up to an hour and a half, you think about form, but after an hour and a half, it’s scale.

-Morton Feldman

wallflower: Well, here it is. The longest, best, worst, and unquestionably most Pynchon, a 1000+ page novel that launches the story of the Traverse family that continues in Vineland and Bleeding Edge, jumps from America to Europe to Inner Asia, incorporates the invention of transfinite numbers, ballooning, and calculus (once again) as metaphors and plot elements, describes the Second Civil War between labor and capital from both sides, it’s a Western, a Carey McWilliams-like L. A. proto-noir, an epic of electrification, a Sophoclean revenge cycle about two families, a Doctorovian historical novel with guest shots for a dozen or so historical actors, a globe- or anyway continent-trotting spy saga, at least three picaresque novels stacked on top of each other, a pastiche of boys’ adventure serials, science fiction, and pornography, and much, much more; Avathoir and I started Conversing with American Vampire and sometimes this feels like if we took the entire goddamn series and superimposed it into one novel. It’s the work of a writer who looked at Gravity’s Rainbow and Mason and Dixon and said “well those are. . .OK, but a bit, um, limited in ambition. Time to go for the Brass Ring, Tommy.”

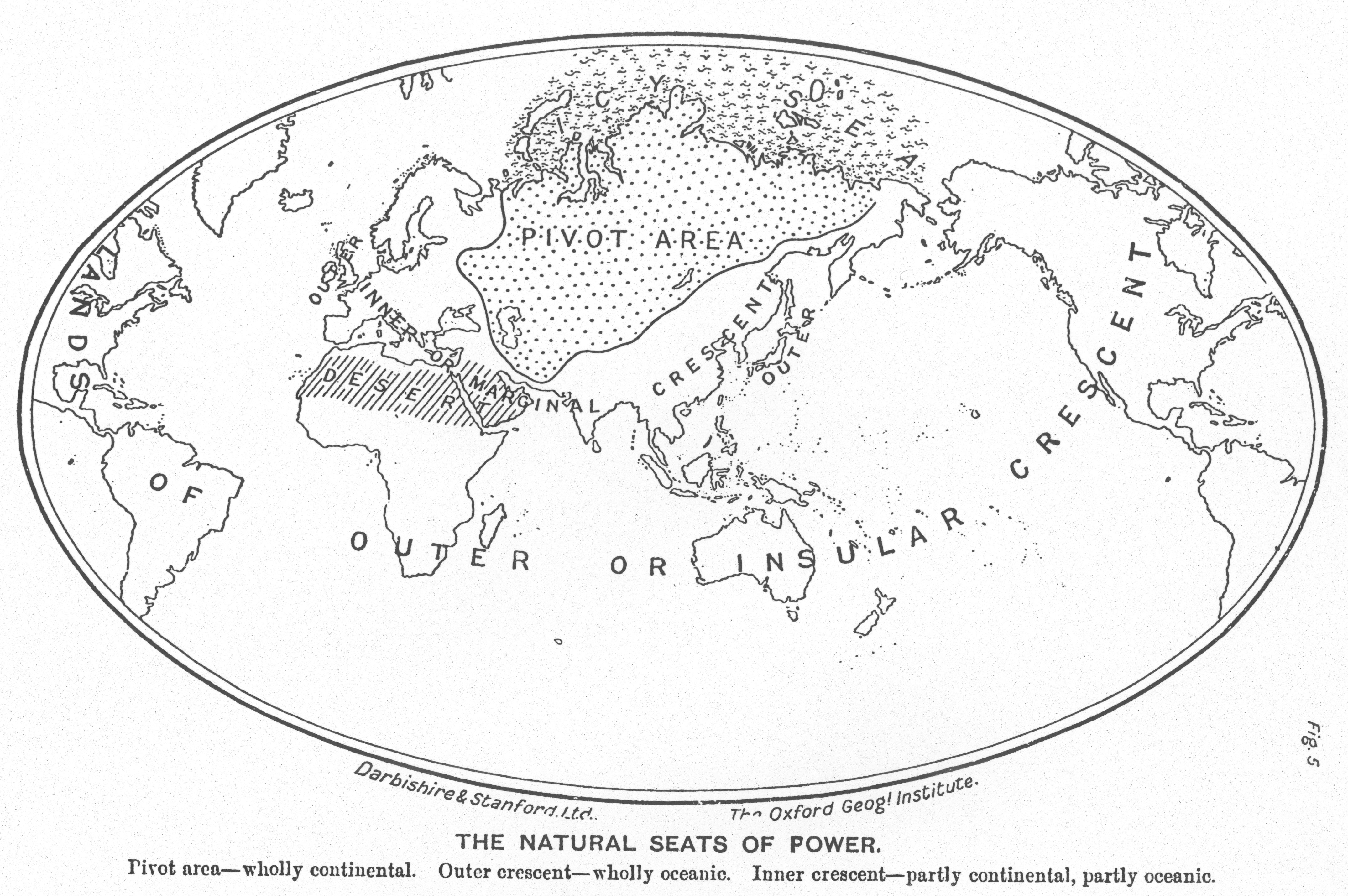

A brilliant mess like this (and it’s both) creates a lot of entry points for a discussion. I’ll take two, really my two favorite aspects. First, this is Pynchon’s rewrite and self-criticism of his earlier works, particularly V. In the Slow Learner intro, he remarked that he spent a lot of time as a teenager reading spy novels and “the net effect was to build up in my uncritical brain a peculiar shadowy version of the history preceding the two world wars. Political decision-making did not figure in this nearly as much as lurking, spying, false identities, psychological games.” Half of V. comes from this, but he goes so much farther here, bringing forty years’ more worth of imagination to it. We get all of the above plus battles above and below the earth’s surface, meat lozenges, people communicating by means of gasworks, phosgene as not a gas weapon but an instrument of light, and secret societies galore. (It’s impossible to write about Against the Day without resorting to lists, which suggests a problem here: so much happens without ever really cohering.) Pynchon dips into the theories of Halford Mackinder, who called Inner Asia “the geographical pivot of History,” and sets a lot of the novel there. He’s gone back to his earlier self and given into the same impulses but on his biggest scale to date.

He also openly corrects that earlier Pynchon; he’s carrying out what he promised in that Slow Learner intro. All of Pynchon’s novels take place in the same universe, with the saga of the Traverses being the essential post-Vineland link, but near the end here, he pulls a unique twist: something in V. didn’t actually happen. V.’s lover, La Jarretière, didn’t die in that Rite of Springish ballet; she faked it: “death and rebirth as someone else seemed, just the ticket. . . .A young beauty destroyed before her time, something the eternally-adolescent male mind could tickle itself with, ” she sez; another pretty clear shot from the older Pynchon at the younger. For all the times he has shifted between what is real and what isn’t, this is the only time he does it to his own writing, and it’s not just intellectually fascinating but also touching.

He also openly corrects that earlier Pynchon; he’s carrying out what he promised in that Slow Learner intro. All of Pynchon’s novels take place in the same universe, with the saga of the Traverses being the essential post-Vineland link, but near the end here, he pulls a unique twist: something in V. didn’t actually happen. V.’s lover, La Jarretière, didn’t die in that Rite of Springish ballet; she faked it: “death and rebirth as someone else seemed, just the ticket. . . .A young beauty destroyed before her time, something the eternally-adolescent male mind could tickle itself with, ” she sez; another pretty clear shot from the older Pynchon at the younger. For all the times he has shifted between what is real and what isn’t, this is the only time he does it to his own writing, and it’s not just intellectually fascinating but also touching.

The second strong element: the unifying theme here is the onset of modernity, more like a set of variations on a theme from (I think) Virginia Woolf: “sometime around 1917, human consciousness changed.” Right away, we start off in that boys’ adventure novel, written in a late 19th/early 20th century style (that is, of its period, just like Mason and Dixon) starring the young balloon-boys the Chums of Chance, who slide across the lines between fiction, reality, and history. (The narrator’s voice is mostly the narrator of their novels, one of which gets read by Reef Traverse while he’s briefly in jail.) Pynchon uses them to come up with the best damn metaphor for modernity that I’ve ever seen, as the Chums and their Russian counterparts, during World War 1, observe the planes, rockets, and balloons of war in a passage that calls back to Gravity’s Rainbow:

“Gentlemen,” Randolph pleaded. He gestured out the windows, where long-range artillery shells, till quite recently objects of mystery, glittering with the colors of late afternoon, could be seen just reaching the tops of their trajectories and pausing in the air for an instant before the deadly plunge back to Earth. Among distant sounds of repeated explosion [sic] could be also be heard the strident massed buzzing of military aircraft. Below, across the embattled countryside, the first searchlights of evening were coming on.

“We signed nothing that included any of this,” Randolph reminded everyone.

This is modernity: the incursion of humanity and its struggles for power into the realms of imagination and the sky; what was once pure or at least unknown becomes the battleground of nations and corporations. This was prefigured in Mason and Dixon, especially its greatest sentence, but now it’s happening in earnest. You can all but see it through the prose: the sense that there is no safe place anymore, that whatever the old world was, good and bad, it was certain, and that time is dead and gone.

Those are the highlights of what I liked here, and we’ll get into what I don’t soon enough. Coming off of this after Mason and Dixon, what are your thoughts? In particular, what did you think about the style?–because more than any other novel, this doesn’t quite sound like Pynchon, and he never used this kind of voice again.

Avathoir: This book.

This fucking book.

wallflower: Oh God, we broke him.

Avathoir: THIS

FUCKING

BOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOK.

Okay okay I’ve calmed down now. The process of reading this book was incredibly unhealthy for me. I read it in vast, hundred page binges, and the last half of the book I read in a frenzy of an afternoon that I was convinced would end with one of us dead. Amazingly, I triumphed.

So you asked me about how I thought about this book, and your description of it as being his best and worst book at once is dead accurate. This is a book which had moments and passages and concepts that just took my breath away (Skip the talking ball of lightning, the Zombrini family, Kit Traverse’s entire storyline, which might be my favorite thing he’s written, with the love triangle of him, Yashmeen and Dally surpassing Roger and Jessica from Gravity’s Rainbow).

At the same time, the sheer scale of this book, along with the things I think it gets WRONG, makes it for me a book that sometimes hits the lows of Vineland, V. and Gravity, and it hits those lows MORE because well…there’s just more of them, and Pynchon is so unwilling to cut that the book ends up going incredibly long stretches between moments that I liked. I was reading in two simultaneous fugue states, one of rage and one of joy as I plowed the pages.

So here’s what I think about this book and where I think it goes wrong: It’s a “historical” novel with an anarchist perspective, but in reality it’s a conservative fantasy novel. Like how for me Vineland is a failure because it mixes up the the prologue : epilogue ratio (it should be REVERSED Dammit), this is a book where Pynchon seems to be trying to deny what he enjoys and focusing on one set of unfortunate facts for a series of another, when he should really just own those tendencies.

You’ve mentioned that Pynchon grew up reading spy and adventure novels, and this feels very much of that type for some of the best stretches of the book, a loving pastiche of every sort of pulp that existed. Chicago in the height of the World’s Fair is rendered as real as any imaginary place (contradiction very much intended) and the Western sections, descriptions of magic, and Venice and Russia are all described in much more fantastical language then anything resembling actual research.

So that’s why I’m pretty bummed to say…I kind of hate the Chums of Chance. The whole idea feels very similar to Alan Moore in League of Extraordinary Gentlemen making Tom Swift into a racist imperialist (which is not incorrect) but he tries to have it both ways: making the subtext text but still trying to retain affection for him in the readers. Sure the ending, where Darby has become a radical and the members all hate each other seem to be him willing to confront it, but it seems like he’s still indulging in the Shit he claims to have outgrown. I counted at least a few sex scenes that made me go “Goddamn Dirty Old Man” in this (still his previous books used to reach double digits, so pretty good right there!) and for all his supposed hatred of the old world in this book, his even stronger hatred for modernity makes this book almost reactionary at times. He enjoys describing the things he finds repulsive, in other words, which is why the best parts of this book are when he abandons the thesis of “the problem of modernity” and throws himself fully into the past. Had the Chums been allowed to be characters of blatant fictions rather than an ambiguity, I would have loved this book a lot more. I have to admit I find the whole “is it real is it fake” thing to be pretty uninteresting unless it has a purpose. In Cloud Atlas (which does it well) it makes the fictions seems stronger, emphasizing the power of stories so that even if they aren’t “real” it doesn’t matter. In most works (Hey Paul Auster I’m CALLING YOU OUT) it just makes the whole thing feel rather…airy, as if the writer can’t commit.

Anyway, is there anything in the wreckage of my mind that you can pick on? This book is almost like a dream, in its construction and prose, and it occupies my mind like one as well.

wallflower: That split, that sense that Pynchon tried to do something he’s not temperamentally or literarily suited for, goes all through Against the Day. More than anything, it’s that aspect of “historical novel with an anarchist perspective” that sinks this for me and for the first time, turned reading Pynchon into a goddamn slog; I believe my exact words were “did Upton Fucking Sinclair write this or some shit?” Around the time of Vineland, Pynchon discovered the history of the American Left, with its strikes, communities, languages, and that discovery gave it so much energy, humor, and insight; with Mason and Dixon, he was able to take that energy and transpose it backwards to a decisive moment. Here, it’s hardened into one of the worst things a storyteller can have: ideological certainty. So many of his novels before were about asking what went wrong in the world, and now he knows: it’s Industrial Capitalism, and by God he’s gonna make sure we know it too.

All of this comes together in the character of Scarsdale Vibe, Captain of Industry, someone so completely out of place in the Pynchouevre that I still can’t quite believe he wrote him. (Dude, you were the guy who made Nazi rocket scientists sympathetic and complex. If this is your act of fucking atonement, you have a long to way to go, alls I’m sayin’.) Vibe is pure capitalist Evil and Pynchon rubs our faces in that with every appearance: every spoken line from him is hateful and cowardly, every action he takes is malignant; he’s so over-the-top and rendered with such precision that I found myself asking something I’ve never said before (and only said once after) while reading Pynchon, a question that’s fatal to storytelling: what is Pynchon trying to say here? (If I’m asking that, it means I no longer believe in the reality of the story, only the intentions of the author.) Maybe he’s going for an iconic/mythic character here, a pure embodiment of that horrible horrible industrial capitalism, but oh wait, double fucking news flash: PT Anderson and Daniel Day-Lewis would beat Pynchon’s ass on this point one year later with There Will Be Blood’s Daniel Plainview. (Which is a neat kind of circular payback, since that was inspired by Sinclair’s Oil!) Actually, no, his ass already got beat over fifteen years earlier by C. Montgomery Burns, funnier, nastier, more memorable, and still alive as of this writing.

Pynchon has done so much great stuff in the past that, like you, I’m willing to extend him credit here and try and answer that question of his intent, even if I don’t like to ask it. If, along with old spy novels and boy’s adventures, he’s trying to parody the Sinclairian “proletarian novel,” he needs to find a different reader to appreciate it, someone who can do that kind of “aren’t you and I, author and reader, a couple of intelligent chaps to recognize this isn’t actually bad writing but a clever imitation of someone else’s bad writing” thing. Or he can just toss this aside (thud) (OW!) and pick up Chris Bachelder’s U. S.!, a much funnier, faster, shorter and yet more expansive parody of and homage to Sinclair, the Hot Fuzz to Against the Day’s It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.

Another possibility for what Pynchon’s doing, and one that leads me back to what I like here, is that he’s choosing not to focus his energy on individual characters and stories and to go more for the big picture–after all, the first thing that happens is the Chums launch their balloon and start seeing the world from very high up, where people get all kinda indistinct-like. Here, as I suggested earlier, it works, and if calling this the one Pynchon work where the ideas are more interesting than the characters isn’t the highest praise I can give, it’s not nothing and it’s sincerely offered. Perhaps my favorite single scene in all of Pynchon happens here, near the dead center of the book, as Chum of Chance Miles Blundell talks with a visitor from the future on a country road in France circa 1905:

“Ten years from now, for hundreds and thousands of miles around, but especially here–” He appeared to check himself, as if he had been about to blurt a secret.

Miles was curious, and knew by now where the needles went and which way to rotate them. “Don’t tell me too much now, I’m a spy, remember? I’ll report this whole conversation to National H. Q.”

“Damn you, Blundell, damn you all. You have no idea what you’re heading into. This world you take to be ‘the’ world will die, and descend into Hell, and all history after that will belong properly to the history of Hell.”

“Here,” said Miles, looking up and down the tranquil Menin road.

“Flanders will be the mass grave of History.”

“Well.”

“And that is not the most perverse part of it. They will all embrace death. Passionately.”

“The Flemish.”

“The world. On a scale that has never yet been imagined. Not some religious painting in a cathedral, not Bosch, or Brueghel, but this, what you see, the great plain, turned over and harrowed, all that lies below brought to the surface–deliberately flooded, not the sea come to claim its due but the human counterpart to that same utter absence of mercy–for not a village wall will be left standing. League upon league of filth, corpses by the uncounted thousands, the breath you took for granted become corrosive and death-giving.”

You don’t need a grip on character to make that moment land, and to make it terrifying, to give the sense of a horror that was literally beyond everyone’s comprehension. Pynchon began his career in V. suggesting the irrevocable break made in our world by the Holocaust; here he locates that break in World War One and makes it even more powerful by showing it from the other side. (Like Gene Wolfe in Peace or Philip K. Dick in anything, he shows us how the resources of science fiction can be used to relate truths beyond the ability of more so-called literary writers.)

Of course, one more way of reading this book is that it’s like a dream, or more like a daydream, Pynchon just letting his imagination and reading run wherever he’ll let it and typing it up without much regard to coherence. (He did say On the Road was one of the great American novels, ya know.) That gets you a lot of stuff no one else could have written, and a lot of stuff he or we might have wished he hadn’t. (I now officially know too much about his sexual fantasies.) As we’re now a day past you waking up from this dream, what’s sticking around? Are you remembering anything else? Is this turning into any kind of coherence–or should it?

Avathoir: I’ve talked before about how Boschian Pynchon can be at full blast, essentially writing landscapes of characters (which is why I think people who complain about those covers of his books that look like Where’s Waldo puzzles are missing the point, as that’s kind of the perfect thing for his work.) so I think the idea of coherence would kind of miss the point in some ways, at least for what he wants. Do I think the book should be more coherent? Yes! I think an ideal version of this book could even be the same length, but with a clearer line dividing what is real and what is not, with the real focusing squarely on the Traverse family, who I really do think (especially Kit) are what Pynchon was looking for in many ways: a multigenerational saga of adventurers and dreamers, who come to an understanding about how to live the best they can within the world. It’s little wonder they turn out to be the ancestors of Sasha and Frenesi and (most importantly) Prairie.

That being said…I still think he fucks them over. It’s too chaotic, too many characters with too many locations, too many things. More than any other book he has written Pynchon takes pleasure in describing the physical world and the objects within it, whereas before I had always found him to take more pleasure in the act of writing, of having sentences that almost seemed to sing. Which…actually kind of sucks from a certain point of view. For an anarchist book, he takes such pleasure in describing clothes, skyscrapers, machines, and food, among other things. Scarsdale Vibe is so sinister that he’s comic and you can tell how much Pynchon hates him, but he’s also clearly enjoying how much he hates Vibe, which is not what you want to do when you make a moral point.

Again I realize I’m basically describing a fantasy novel here, and now I’m thinking more and more that it actually kind of is: it’s Pynchon reverting back to a state of fantasy he had seemed to abandon with his last two books: one where there are sinister things and an almost Manichean like tendency to view the world. It occupies about half the book, while the remaining half is dedicated to the lives of families trying to work through shit.

This is best exemplified with Dally, who I think might actually be his best female character: there’s no weird sex with her, she’s got clearly defined characters around her, she has development and growth, gets a great love story and then loses it. It’s weird almost how much better she is then most of Pynchon’s previous attempts at women, and I can’t even chalk it up to writing her as a child because well…we all know about some of that stuff.

So to answer your question after saying my pluses and minuses, I guess it IS a dream, but that’s not always a positive thing. I think the book’s at its best (and he reaches some incredible highs) when he foregrounds characters over ideology and prose. Who are some of the leading lights in this particular cast for you, and do you think he ever really hits the perfect trifecta of setting, prose, and plot (which we’re adding character development to)?

wallflower: I like that we both found our favorite characters among the Traverses and Traverse-adjacent characters. For you, it was Kit/Yash/Dally, for me it’s Webb’s daughter Lake, her husband/Webb’s killer Deuce Kindred and his buddy and fellow killer/rapist Sloat Fresno. Their story is ugly and touching and so damn tricky to tell; Pynchon brings off the near-impossible challenge of making Deuce sympathetic without being any less evil, and showing Lake as a victim without denying her agency. All three of these characters make choices and have to live with the consequences, forever; there’s no resolution, not even the partial resolution of Reef watching Foley Walker gun down Vibe, just the worst kind of what Vineland called “sad human shittiness,” all the way to the final chapter. You’re right that the best stuff here comes with the characters over ideology, and probably why Lake/Deuce/Sloat works is because there’s no ideological solution to be found with them. That’s the kind of thing that storytelling does best.

My runners-up here would be the Chums of Chance–I like them, you didn’t, but that’s probably because I see them as presiding spirits and opportunities for great jokes more than proper characters

“Eehhyyhh, I betcha I could even pull out my knockwurst here and wave it at ‘em, and nobody’d even notice,” cackled Darby.

“Suckling!” gasped Lindsay. “Even taking into account considerations of dimension, which in your case would require a modification of any salcacian metaphor toward the diminutive, ‘wiener’ being perhaps more appropriate, nonetheless the activity you anticipate is prohibited by statute in most of the jurisdictions over which we venture, including in many instances the open sea, and can only be taken as symptomatic of an ever more criminally psychopathic disposition.”

“Hey Noseworth,” replied Darby, “it was big enough for ya the other night.”

“Why, you little–and I do mean ‘little’–”

and because they get Against the Day’s great final scene and last word, “grace.” The Chums, fitting for fictional characters breaking into the novel’s reality, exist somewhere between symbol and person. It makes sense that they get to interact with not just historical figures but also the travelers from the future, from the world of Pynchon’s later-in-time/earlier-in-publication novels. Pynchon seems to be openly enjoying these characters, like you said, and that was infectious. Also, some of the historical sequences, like the run-up to the Ludlow Massacre late in the game, are great, and I really appreciated all the math geekery–Pynchon goes way past the differential calculus metaphors of Gravity’s Rainbow and brings in the Weierstrass functions, Hamilton’s (no, the other one’s) quarternions, scalars/vectors, the imaginary axis, the Riemann ζ-function, and the constant in integral calculus and gets it all pretty much right.

By the way, I’m so glad you said how much Pynchon enjoys hating Vibe, because as awful as he is, that hate was so clear it flipped my sympathy more than once. When Vibe’s bodyguards gun down the anarchist artist Tancredi, I was cheering as much as Vibe was, and thinking exactly what he was: “You pathetic little pikers. . . .who–what–did you think you were up against?” That’s the right response to any punk who brings conceptual art to a gunfight. (For those who haven’t read this: I am not making that up.) If you’re gonna write propaganda, a good rule is Don’t Make Your Reader Sympathize with Your Villain.

Again, this fits in with your larger point, the split between Pynchon’s newfound ideological commitment and what he enjoys doing. A good summary of how I feel about Against the Day is that although Tancredi fails as a character, I enjoyed Pynchon’s descriptions of his paintings. That’s the split here: he loads the novel with tangents of description that are energetic and wholly Pynchonesque but also with characters and scenes that feel obligatory in a way that’s new and just plain sucks. (Let’s go back to the Slow Learner intro for some anticipatory self-criticism: “The lesson is sad, as Dion always sez, but true: get too cute, too conceptual and remote, and the characters die on the page.”) The late-novel love-triangle between Yash, Reef, and British secret agent Cyprian Latewood is one of these, one that feels staged entirely for our benefit rather than coming from any character necessity: by the end of this story, Yash feels like all four of Firefly’s female “sexual utopias” compressed into one (using the term loosely) character (thanks to DJ JD for explaining this), Reef feels like Pynchon saying “hey wouldn’t it be cool if the super-macho cowboy went all gay?” and Cyprian, both on the personal and authorial level, just exists to serve the other two. Again, reading this, I’m not believing in the characters (especially not Cyprian), I’m wondering what the point of all this is.

Against the Day tries for something like Don deLillo’s Underworld or John Dos Passos’ USA trilogy or War and Peace, getting an entire age between two covers, but what it resembles the most, in scale, structure, and degree of success is Norman Mailer’s Harlot’s Ghost. Mailer always had a problem of loading his work with more Meaning than it could bear (no surprise that his best work, The Executioner’s Song, was the one where he most deliberately effaced his voice) and he went all-out here, trying to make the whole novel a demonstration of a philosophical System. (It’s like he tried to write what he thought a Pynchonian novel should be.) With Harlot’s Ghost and Against the Day, you get overlong, overstuffed, undercoherent works where the author keeps including what they’re best at (for Mailer, it’s the way white men fight) and then undercutting it with what they’re not. I wish I could remember who landed the best criticism against Harlot’s Ghost, because it works here too: this book tries to do nine or ten things at once. If it tried for one and succeeded, it’d be good; if it tried for three or four and succeeded, it’d be a damn masterpiece, but it tried for too much and succeeded at too little.

Avathoir: Wow, I did not expect Lake to be your favorite Traverse, largely because in many ways her love triangle seems to be something out of Rainbow, of a woman having gross, weird sex with a rapist and a murderer, marrying one of them, as if he wants to titillate us with tabooness in both what’s going on and who’s doing what: it’s sort of like if Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid just dropped all the subtext and cuteness and William Goldman just said “YES they’re all having sex with each other NO QUIPS IT’S WHAT’S REALLY HAPPENING”. At the same time, it’s nothing like his earlier work because well…it seems as if he actually thought about it instead of jerking off (this would probably be a good time to mention a niece of Pynchon’s is an acclaimed and innovative porn director. She has yet to get him to do commentary tracks, alas) and perhaps more importantly, he saw it as a choice rather than as something to be the subject of shock, which is always more shocking in a strange way.

I also want to emphasize again that I only kind of hate the Chums of Chance: In many ways Pynchon succeeds with them, and the initial pages where they’re flying around, bumming around Chicago, and going on adventures work as a pure adventure story and an affectionate tribute/parody thereof because it’s clear he loves them, and I have to admit I end up loving them too in these moments. The problem is that Pynchon doesn’t want to love them: for a man with no capacity for shame, he has a large one for embarrassment, and the Chums seems to be something he wishes he didn’t like, which is why, despite their excellent ending, he has to undercut it with him saying “I’m cool, guys! I’m still with the kids! I think they’re all a bunch of racist imperialists just like you!” And he may well believe that! But that’s not what’s in his heart, and I would love if, one day going through his papers, we find out he wrote a whole series of miniature Chums adventures (or at least a very good world building guide) for us to enjoy without the desire to Make a Statement standing in his way.

Making a Statement in fact seems to me where this book goes wrong. Pynchon has not written books as ambitious as this (if only in terms of scale), but he’s written casts just as large and books which have a clear moral purpose. The difference here is that for the first time, perhaps because he got his AARP card or because his kid was becoming an adult, he wrote a book whose intentions regarding morals and scale were put front and center, and he poured everything he had into making it so that it could not be mistaken. This is in many ways a very accomplished book, but it feels like the One He Wants to Be Remembered For, and those novels usually never are the best in the careers of their writers.