A nearly objective measure of the necessity of J. S. Bach to the Western musical tradition is that no other composer has been performed in so many different ways. Bach’s music launches from the Baroque practice of creating multiple arrangements of different compositions (so a violin concerto, cantata, harpsichord concerto, and keyboard suite might all come from the same music) and continues into our world and instrumentations he could never have considered or imagined: solo piano, string ensemble, full orchestra, recorder quartet, scat singing, jazz combo, steel drum band, string quartet, marimba, rock band (Procol Harum did this the year before with “A Whiter Shade of Pale”), Casiotone, MIDI generators. I cannot imagine another artist for whom the ideas of “period instruments” or “authenticity” make less sense, because it’s Bach’s understanding of the fundamentals of music–melody, harmony, texture, counterpoint–that makes him work in just about any arrangement. (See also: Shakespeare, William.) This is one reason why Wendy Carlos’¹ Switched-On Bach isn’t a joke or a cash-in on a 1960s trend (although it became the best selling classical album of its time) but rather one of the strongest affirmations of Bach’s music and legacy.

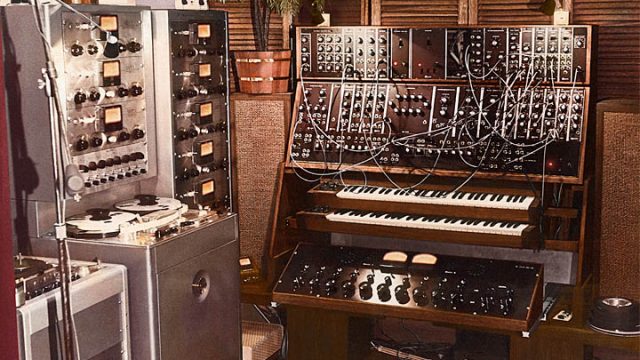

In 1968, electronic music was still a novelty, both in popular and classical music. (I’m making a distinction between electronic instruments and electric instruments that amplify acoustic sounds.) Electronically produced sound had met up with the wave of modernist classical music around mid-century and led to the development of musique concrete and tape-based music; work in this field was done by composers like Edgard Varese, Iannis Xenakis, and Karlheinz Stockhausen, who wanted to use electronics to create radically different sounds and ways of assembling them. (Stockhausen’s beeping and booping Kontakte is the definitive work of this genre.) Synthesizers that allowed for both the creation of new sounds and the means to play them were just getting developed for the general public in the 1960s. Carlos actually came out of the earlier tradition, studying with Vladimir Ussachevsky and Otto Luening at the seminal Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center. An audio engineer by training, she worked with Robert Moog (rhymes with rogue) to develop a synth that was touch-responsive and somewhat portable. (“Portable” here means “deliverable by truck.”) That synth became the basis of Switched-On Bach; Benjamin Folkman, who co-produced, said “two years ago, this album could not have been made.”

What made this way more than a novelty record, what keeps it interesting almost fifty years later, was Carlos’ level of skill and commitment. Synths have developed further, but that doesn’t change the accomplishment–the sounds are dated, the music is not. As she’ll tell you, the advantage of electronic music is the freedom it gives you, especially in what she calls “the four T’s”–tone, touch, timing, and timbre. The disadvantage is the same: you have to make many more choices, and make them well. Moog’s development of a touch-sensitive keyboard allowed her to work with touch and timing; Bach’s mastery of the diatonic and chromatic scales solve the problem of tone; and Carlos’ greatest achievement comes in the range of timbre, the color of the sound. (She notes, by the way, that it’s an achievement born of necessity: synths of the time couldn’t handle legato, the shifting of one note to another, so she had to switch off instrumental colors to obscure that lack.) To create different sounds on a Moog, one begins with basic waveforms–tones–and then alters them through patching the sound through different modules in a way that’s almost tactile, like sculpting or mixing paint, and that requires a lot of patch cords. She’d go right on developing that skill with co-producer Rachel Elkind, resulting in her iconic scores for Stanley Kubrick.

What makes Bach so persistent is also what makes him so adaptable to electronics. His music doesn’t depend on the mass of the sound in the way, for example, Beethoven’s 9th or Shostakovich’s 7th symphonies do. It doesn’t depend on the specific characters of instruments; given the number of times he adapted or rearranged his own music, it couldn’t. Bach relies on what may well be the essentials of music: how one voice sounds against another, how recognizable musical elements–melodies and harmonies–get traded between different instruments and groups. Unlike symphonic music, Bach operates on the virtue of clarity, and whatever you think of the sounds Carlos created, you wouldn’t mistake them for each other. Considering music as “the art of memory,” Bach went farther than anyone else in how that memory operates, calling up fragments and letting them fall away, pulling together different things into a coherent whole–his favorite technique, the fugue, has been compared to the structure of a classical rhetorical argument.

That’s what Carlos realized so well here, and she used the ability of electronics to go far beyond what was possible with acoustic instruments in the realm of timbre. You can hear that in her version of one of Bach’s best known pieces, the C-minor prelude from The Well-Tempered Clavier, book 2. In Folkman’s analysis, “for three-quarters of its length, it behaves like any ‘arpeggio’ prelude, content to make its effect through the building momentum of its characteristic figure. [Bach also uses this trick in the C-major prelude from Book 1 and the opening of the First Cello Suite.] Then, just as it has reached an impressive climax, things go awry: the bottom voice seizes the floor for an angry solo, the characteristic theme flies into a tailspin, and a passionate recitative is required to restore order.” Carlos realizes not just the music but this reading of the music here:

First, by heavily mixing noise into the first part of the prelude, she turns what could be a flowing piece of music into percussion; it’s almost a drum solo.² (The Swingle Singers have done a lyrical acapella version of this that Kevin Smith worked into Chasing Amy.) Then she does something that would be flat-out impossible on a keyboard in 1968: she almost completely switches up the sound for the climax. The new voice isn’t just distinguished by range, it’s effectively a completely different instrument that’s stormed in, creating way more tension than just one instrument could have achieved. The final sounds here are again different, creating the feeling of different characters, not just voices.

Even with Bach’s music for ensembles, Carlos pushes past what was possible (or at least manageable) for physical acoustic instruments. In the climactic passage of the first movement of the Third Brandenburg Concerto, she seems to invent a new instrument for each entry of the melody:

The Brandenburgs have some of Bach’s most exuberant use of repetition, and Carlos exploits that to the fullest here; she uses the thrill of recognition as each voice comes back and augments it with an equal thrill of discovery. (She also has each voice come in from a different direction.) One of the characteristics of the Brandenburgs is their sheer joy, and Carlos found a way to crank it up.

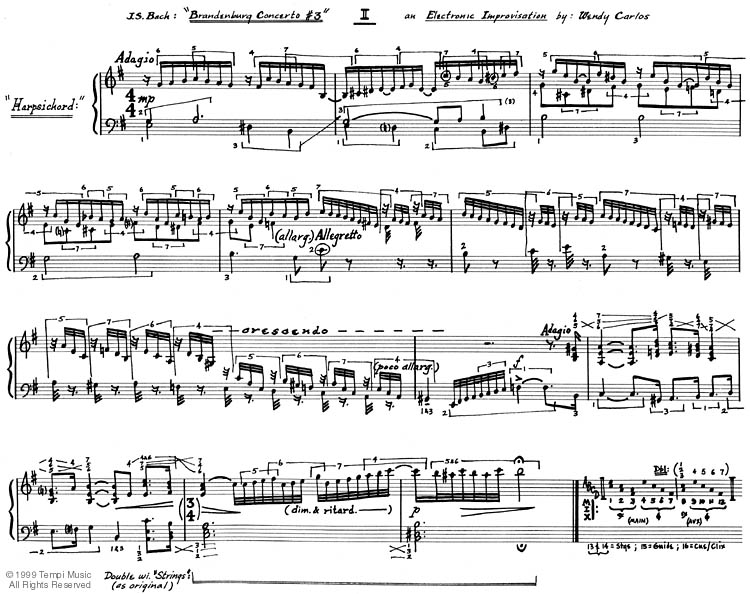

The middle movement, by the way, was left unfinished by Bach–he only sketched in a couple of chords for performers–usually harpsichordists–to improvise on. Glenn Gould³ noted that usually this meant “every conceivable combination of arpeggiated clichés” got played here, and that Carlos came up with the 1960s equivalent here, “the best inside joke in the music business ‘68”:

She provided a much more restrained version for 1979’s Switched-On Brandenburgs, but c’mon Wendy, we don’t music with good taste, we want music that tastes good.

In other works, Carlos goes for a more deliberate application of synth effects. Her version of the E-flat major prelude and fugue (book one, Well-Tempered Clavier) goes full orchestral; she first creates voices that have a lot of harmonic oomph and then gives them a distinctly instrumental feel through the sound envelope. The envelope of a sound is how the sound arises from and falls back into silence, and here, the sounds take a while to fade as strings or horns would. She plays the prelude in an even, slowish tempo and slips in lots of little crescendos. (All of this has to be planned, executed, and carefully mixed, one voice at a time.) She plays that off against a quicker notes, giving those voices shorter, more percussive envelopes and brighter timbres. It’s reminiscent of Leopold Stokowski’s Bach adaptations for big loud orchestra; both of them construct something dramatic and grand from the rigorous architecture that’s in the notes.

Just as importantly, Carlos knows when to do what she’s supposed to do, and then stop. Although she meant this album as a demonstration that electronics could realize more traditional music, she never shows off; she always considers the logic of the music itself first. In the Two-Part Invention in B-flat major, she uses only a couple of voices that contrast elegantly with each other, a straightforward charcoal sketch in contrast to the colorful blowouts of the prelude/fugue and the Brandenburg:

This is a simple orchestration of a simple piece; in addition to only using two voices, she doesn’t alter the tempo or the dynamics here. If the earlier prelude made the synth into an orchestra, here she makes it a keyboard instrument with a slightly expanded range of sound, and that works just fine.

Switched-On Bach, like a lot of great art, has a kind of split-diopter effect in its history: it’s a work of eternity that could only be made in its time. Not just the sounds but the exuberance of it belong entirely to 1968. (I’ll assume that not everyone who listened to this did so without chemical enhancement.) It fits right into the sense of expanded possibilities, and the nostalgia, of its time; there’s always been a substantial and perhaps even majority component of progressive thought and culture that’s actually retro, claiming to return to a pastoral and usually imaginary past. Using Bach, though, goes beyond nostalgia to engaging with some of the absolute values of music. Carlos’ Clockwork Orange music shows us what Switched-On Beethoven would be like: haunting, powerful, but much more specific to a composer and to the film. Bach’s rigor led him to pursue music that wasn’t just beautiful (and it often was) but necessary–music that could not be any other way than it was. Carlos adapted him in the same spirit, and that’s why this album will endure.

¹Carlos was already in the process of transitioning from male to female at the time of Switched-On Bach. The idea of an identity that persists across genders and bodies meeting up with a music that persists across centuries, orchestrations, and technologies is so metaphorically potent that I can only assume the Wachowskis simply haven’t yet come across her story–their version of 32 Short Films About Glenn Gould to join the universe of Cloud Atlas and Sense8.

²Carlos remastered and reissued this (along with its sequels) in 1999, and included a lot of early experiments and descriptions of method as bonus tracks. The early version of “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring” shows that she had that noise-based sound in mind from the beginning but, um, overdid it:

³Gould had always proclaimed the dominance of recorded music over live performance, which was controversial as hell for a classical performer of his time. (He retired from public performances in 1964.) Unsurprisingly, he was an early champion of Carlos and Switched-On Bach, and called her later version of the Fourth Brandenburg Concerto the best of any kind he’d ever heard.