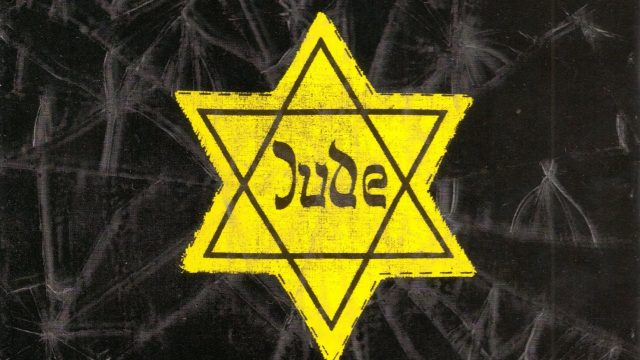

Don’t fuck with the Jews. (Munich)

If it’s not a contradiction to say so, the defining element of John Zorn’s music is how he transitions between musics. Anton Webern’s brief pieces depend on the arrangement of different notes and timbres (usually bound by a twelve-tone row) in the time of the composition as Joseph Cornell arranges elements of sculpture and image in the space of his boxes, but Zorn is about what happens between the sounds, the shift from a jazz riff to a screeching guitar to a cartoon gunshot to a quiet solo piano. He’s made a lot of noisy pieces, but this is music, not noise, and an incredibly diverse music. (His Masada Songbooks show him to be just as adept at coming up with beautiful melodies; Dark River shows how much he can do with almost no sound at all.) Perhaps his definitive work is Cobra, a set of rules for improvisation that give the performers the chance to block, subvert, and switch each others’ music off and on–it makes any ensemble sound like one of Zorn’s. All of this makes the seven-movement suite Kristallnacht the most diverse 46 minutes of music I know, taking scree jazz, folk tunes, found sound, heavy metal, chanting, lyricism, funk, and marches and binding them all together into a history of the European Jews from 1938 to 1948, from the titular Night of Broken Glass to the founding of Israel.

Zorn and many of the performers here came of age in the New York scene of the 1970s and 1980s. I don’t usually go for structural analyses–attempts to tie the disparate arts of a particular time and place together–but the music of Zorn and associates like Arto Lindsay’s DNA, Philip Glass, Patti Smith, Laurie Anderson, Lou Reed (his song “The Blue Mask” is the definitive work of its time and place), the paintings of Robert Longo, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Julian Schnabel, David Wojnarowicz, and the films of Martin Scorsese all feel like they have something in common, as New York shifted away from punk and into the AIDS-ravaged 1980s. The common elements are energy and precision, and they’re all over these works. There’s the speed of punk but not its absence of professionalism; all the effects are carefully worked for and applied. Zorn needed that kind of skill to keep his music listenable at all; even in the noisiest, screechiest performances, everything is in balance, everything matters. (Kristallnacht will go out of balance at one point to devastating effect.) There’s also the anger as AIDS kept spreading, almost as fast as ignorance about it, and that informs so much of these arts. (The biography of Wojarnowicz, Fire in the Belly, is the best thing I’ve read on this particular moment.) By 1993, Zorn had taken these elements and developed not just a style based on them, but something closer to a school of arts.

Zorn’s Judaism has become increasingly essential to his music, incorporating not just melodies but Jewish subjects in his music; to take just one example, his 1996 string quartet Kol Nidre was named after the prayer to open services on Yom Kippur–“a time, the Torah says, to afflict your soul.” (Zorn adds that he wrote this piece “at one sitting in less than half an hour,” that magnificent bastard.) The liner notes to Kristallnacht include a passage from Edmond Jabès where he says ”but it is precisely in that break–in that non-belonging in search of its belonging–that I am without a doubt most Jewish.” (The CD packaging is exquisitely laid out, with photographs, epigraphs, and titles all well-designed and arranged.) That feels like a mission statement for so much of Zorn’s music since the 1980s. He began his career with loud, chaotic jazz (much in the tradition of Ornette Coleman, and his Spy vs. Spy is a great and inevitable tribute to Coleman) but, without ever getting quieter or more ordered, his music has become deeply complex, referential, involuted–Talmudic would be the exact word here. Zorn has broadened that search past his own music: in 1995, he founded the Tzadik record label, with a sublabel for “Radical Jewish Culture,” including a lot of his own works and those of other Jewish musicians.

Among other things, Kristallnacht is nearly the best work I know of about the Holocaust, and that calls up two other works: first, another one from 1993, Schindler’s List. Like a lot of Spielberg’s best work, Schindler’s List was a skillfully crafted piece of pop art, at its most moving when I felt the distance between the story it told and the story Spielberg wanted to tell. Nothing from Schindler’s List has stayed with me as much as the sight of all the Jews who don’t try and comfort Oskar Schindler at the end, or the imagination of all the Jews who weren’t saved. All Spielberg’s instincts wanted to make an uplifting rescue movie, but that can’t happen against the background of the Holocaust, and Schindler’s List was most powerful as that failure. If the film deserves its most oft-made criticism–it portrays Jews as victims rather than as agents of history–that also raises the question: was there any action or agency that could have made a difference in the Holocaust?

That’s not a problem for Kristallnacht, for reasons I’ll get to, and it’s also not a problem for the only better work I know on the Holocaust, Art Spiegelman’s two-volume comic book Maus. Even then, Spiegelman and Zorn have different goals with their works. Maus is multilayered work of storytelling, as much about the everyday details as to how Spiegelman’s father Vladek survived (knowing just how to stitch a shoe can save your life) as to the legacy of survival, what it did to him, Spiegelman’s mother, Spiegelman himself, and to the world. So many things are laid out on every page (it’s as complex as Watchmen but less obviously so) and so many emotions get triggered because of his simple, affecting drawing style, not to mention portraying Jews as mice and Nazis as cats. (Spiegelman occasionally appears as himself, sometimes as a mouse, sometimes in a mouse mask.) It’s history, journalism, memoir, and metafictional inquiry all at once.

Where Kristallnacht differs is that although there are elements of narrative to it–that is, cause-and-effect that creates change over time–it doesn’t try for anything like the documentary presence of Maus. Zorn may use some found sonic material here, but Kristallnacht stays well within the realm of music, which sometimes touches on truths beyond any kind of representation. Kristallnacht doesn’t try to describe what happened, but brings us into an elemental confrontation with a decade, makes us feel, right down to our nervous systems, the shit expelled from prisoners as they clawed at the doors of Auschwitz, the flesh ripped by the bullets in the Six-Day War. Spiegelman builds an intricate monument upon history, but Kristallnacht feels like history itself, the heart of violence behind it, all twisting muscle, sinew, vessels, and blood.

In our language, “essential” often gets misdefined as “pure,” and the essence of history is anything but. That’s why the diversity of Kristallnacht is as necessary to it as the skill of the musicians or the impact of the noise. Elements of the tracks reverberate back and forth, and each track has its own character, even its own genre. Like a good literary work, the elements take on new meanings from their contexts–what could be sentimental or even funny on its own becomes something much different depending on everything going on around it. Even the noise elements here, taken on their own, are not the noisiest I’ve ever heard, but they gain much more power by everything going on around them. For all the sonic diversity, the through-line here, the journey of the European Jews, is linear enough to be considered track by track. (Also, I will include the Hebrew titles as Zorn did, as Hebrew and Cyrillic are the two most boss alphabets ever.)

1. שטטל (Shtetl: ghetto life) Starting with a shofir-like trumpet line that works as a riff and a call to prayer, the other performers come in here with a sense of precision and delicacy, a balanced tapestry of strings, reeds, percussion, and drones. The melodies themselves are Jewish, muscular, yearning; we’re plunged straight off into a world of 1930s Europe with nothing but music.

After this opening, Zorn shifts (because he’s Zorn) from music to collage. In a definition I’ve used before, collage differs from composition in that the elements of a collage keep their identity and difference without becoming a unified whole. Zorn’s love of shifts makes him one of the masters of this genre, and he often constructs collages on specific subjects; his twenty-minute Spillane is one of the greats. Here, the music gets overtaken by stomping feet, the hysteria of Hitler’s voice, chants of soldiers; right away, what was foreboding turns into violence, and then the other elements depart briefly for a dancelike moment, as balanced as the opening. As that fades, there’s a scratchy recording of The Merry Widow (Hitler’s favorite piece of music), and the sense of a people, a culture, disappearing into an abyss. Think of Wallace Shawn’s line in The Designated Mourner: the moment when he realizes there is no one alive who understands John Donne anymore. The silence that follows may be the most purely awful moments in Zorn’s catalog, maybe in all of music, even if you don’t know what’s coming next.

2. לא עוך (Never Again)

Caution: Never Again contains high frequency extremes at the limits of human hearing & beyond, which may cause nausea, headaches & ringing in the ears. Prolonged or repeated listenings is not advisable as it may result in temporary or permanent ear damage. –The Composer. (from the liner notes)

The sound of broken glass, everywhere, distorted and rising, crashing over and over and over again, mixed with other sounds that may have begun as screams but altered until they’re close to pure sine tones, and sounds that are pure sine tones, other cries altered so they’re closer to amphibian than human, and over all of it the highest-frequency sounds, something that can’t be heard as we usually mean it but only sensed. There’s no ground to this, no lower bassline, and that comes across as a violation; maybe it’s because in our everyday listening, there’s always a sound under everything, wind, heartbeat, local noise. Here, the music is unanchored and flying all around us, the kind of noise that dominates everything around us, no matter the volume.

There are breaks where the sound dies down, goes into the lower registers and then stops, the highest-frequency drones gone. In its place are footsteps, windlike sounds, the ground of lower tones reasserting themselves, but it’s hopeless, it’s only a brief respite before the crashing and shrieking comes back. With each repetition it gets denser, more voices and more violence; with each disappearance of the noise more recognizable elements come in–the military cries of the first movement, voices of Jews at prayer overlapping, Mark Feldman’s violin.

This goes on for ten minutes, Zorn’s portrayal of the last horrific descent of Europe from Kristallnacht into the executions, the killings by carbon monoxide and then the death camps. Zorn doesn’t go for a literal portrayal but the sound of a culture trying to hold on against a violence rendered in terms of sonic frequencies. There’s a bizarre tension here, trying to use an art that’s horrible at representation to represent the unrepresentable–and it works, because לא עוך doesn’t portray, it attacks. This isn’t about understanding because there is no understanding. This is confrontation, a demand for us to live in a world where the Holocaust happened. This is what it sounds like to live with that.

I’ve been listening to this since the mid-90s; I make it a point to do so at least twice a year. This music, in particular this track, has influenced me and my thought in at least one simple, measurable way: after hearing this, I can never take seriously any discussion about how such-and-such a work attacks or challenges or problematizes or makes the audience uncomfortable. Listened to properly, this track attacks me, and not in any kind of metaphorical or philosophical way. It has damaged me in a way that can be measured and will no doubt manifest itself as I live longer: because I heard this now I will hear less later. It is necessary that I do this. All creativity, really from the invention of language, has made us live in a larger world and living in a larger world means to be part of its pain, and this has nothing to do with the Enlightenment virtues of reason or life expectancy or “the greatest good for the greatest number.” Listening to לא עוך is the minimum price to be paid for living in the world after the Holocaust.

3. גחלת (Gahelet: embers) A Requiem without the slightest pity or sentimentality, these three and a half minutes begin with droning accordion tones that sound like Pauline Oliveros’ massive ambient compositions. Zorn holds to the same compositional balance as in the opening of שטטל, with little contributions from the other performers shading the drone. We do hear the crackling of embers, and the yearning tones of percussion, violin, and keyboards sound like a return to life, but not human, more like the few plants still living after the blast. When the chants from the previous movement come back, there’s no triumph; as the volume rises throughout, there’s no exaltation, only the fact of strength. More literally than Pettersson’s Sixth Symphony, this is the sound of the barest survival, the voices that made it. Zorn makes no concession to the idea of the suffering that ennobles, the bad that produces good, only the duty of the living to live.

4. תיקון (Tikkun: rectification) Here, Marc Ribot’s guitar, which has shaded around the edges of the previous movements, comes to the fore. He and Feldman come together in a duet that belongs to the tradition really kicked off by Bela Bartok, what could be called the genre of abstracted folk music, compositions and improvisations that take as their base works from a specific culture but then get developed into something almost unrecognizable, something that belongs to a people but could only be made by individuals.

It’s here that Kristallnacht, and the European Jews, launch in a different direction. Rectification is not restoration; there is no going back, and the melodies here have a distinct feel from the traditional melodic material of the first three movements. The music here is questioning, the guitar and violin not so much making statements as continually discussing, not quite arguing. The time of mourning has passed, and what emerges in תיקון, so surprisingly, is a dance. It’s not celebration, it’s may be the coming together of a community but with more than a little threat to it; what I hear more than anything else is the Judge in the final pages of Blood Meridian: “He is dancing, dancing. He never sleeps. He says that he will never die.”

5. צופיה (Tzfia: looking ahead) The second-longest and perhaps most complex and most Zornian movement (if this turned out to be a Cobra improvisation, I wouldn’t be surprised at all), this elaborates the structure of תיקון, going in several different directions without ever fully cohering, or intending to. Where previously we’d heard a duet, we now get not just the full instrumental force here but also some new sounds and musics–gentle riffs on the vibraphone and David Krakauer’s clarinet, some almost lounge-like vamping (“we’re gonna take a break now, don’t forget the genocide or to tip your waitress,”) staccato blares from the trumpet and ensemble like Iannis Xenakis’ Akrata, piano and accordion stings. We also hear elements from the preceding and following movements–the chants, the melodies, the shrieks; more than any other element, Zorn brings back an overlay of LP record static, as if we’re hearing some kind of jam session circa 1954, marking this as past and future all at once.

Many many people, myself included, have claimed that music isn’t simply a representation of thought but a form of thought. What this feels like, just as שטטל felt like history, is the making of history. There are elements of a known past, even the known past as it relates to this recording, but there are also possible futures coming up here, getting considered, accepted, and rejected. If תיקון was a discussion, this is argument and action. When Krakauer replays that call-to-prayer that opened שטטל, it doesn’t drift off into the rest of the movement but gets followed by the ensemble, rising, swirling lines around the trumpet, not taking over but assembling. At the beginning, the sound was history, of a community that was static. Now, choices have been made, a direction found; תישארב–the Hebrew “In the beginning”–would work equally well as a title here.

6. ברזל (Barzel: iron fist) The shortest and simplest movement, this is a

Glenn Branca-like wall of drum and guitar noise. Specifically, it’s like where Branca usually ends up, with the drums reinforcing the guitars to create something that really isn’t music anymore, but power. (The shrieks above the noise also owe a lot to Branca.) The voices that have been moving in and out since לא עוך come back in a few slight breaks to the noise; the feel here is of power uncontrolled but somehow contained. There’s still so much discipline to the noise here, an ongoing nuclear explosion for now trapped in a chamber.

7. גרעין (Gariin: nucleus–the new settlement) From the questioning of תיקון onward, so much has been anticipated; now it’s here. Again, Zorn returns to the structure of a quiet opening with the different players joining in–William Winant’s percussion kicks things off (the bass drum is quietly, perfectly mixed). Then, Mark Dresser comes in something entirely new to Kristallnacht, a bassline that’s a little funky (in any other context, it would be almost comic), more than a little menacing, but most of all, directed. The discussions of תיקון and צופיה , the power of ברזל now has a purpose. This isn’t just power (and certainly not the power of righteousness) but force, something that can be applied, something than can be targeted.

Ribot’s guitars have now gone full electric, not turning into a wall of noise like before, not screaming in an imitation of voices, but grinding out solos. It’s not freeform, though; each guitar line is tied rhythmically to the bass, which keeps driving on–and then speeding up. It’s unavoidably military, a massed march that can only go forward and destroy whatever’s in its path; there’s no conversation anymore. Even the things that might be voices here are barking commands, but in a way that’s decisively different from what we heard in שטטל, because these aren’t the Germans giving orders anymore.

It is 1948 now, and what we’re hearing is the founding of Israel and everything that means. Kristallnacht ends in what Tarantino showed in a comic-book style (I mean this as a compliment) in Inglourious Basterds and what Spielberg and Tony Kushner played in such a disquieting morality in Munich: this is the sound of ownage and particularly Jewish ownage, something appropriate for the only religion to ever have its own submachine gun. (Also Wonder Woman.) Understand: there is no equivalency here between the Holocaust and Israel; the sequence of the tracks, their titles and distinctions create not equivalence but cause and effect. What Zorn creates here is the truest expression of what never again really means. He finds, without attaching any morality to it (the march here can be triumphant or terrifying depending on which side of the Uzi you’re on), the violence in Jewishness and its necessity, and you can read David Ben-Gurion’s words alongside גרעין and not miss a beat:

It is beyond mortal power to bring back to life six million who were burned, asphyxiated, and buried alive by the Nazis. But our six million brothers and sisters who went to their deaths have bequeathed us a sacred injunction: to prevent such a disaster overtaking the Jewish peoples in the future and to do so by the Jewish people being an independent people in its own land, capable of resisting any foe or enemy by its own strength.

As the last sounds of גרעין drift off, not hitting any kind of resolution but simply going away–for now–it’s a reminder that the story here has not ended, that this music will and must always be with us; violence, once introduced into the world whatever its morality, might never leave. Almost a quarter century after this was released, the Middle East is not at peace and the Nazis aren’t as gone as we thought they were. This is not history, if it ever was, and it’s often the power of art to make us feel things that were there all along. Kristallnacht does that, and the terror and anger of listening to it comes from the way Zorn makes its abyss look into us. The absence of sentiment or triumph here, the force of the musical ownage, the way that music can embed itself in our lives, all make this not simply one of the best but one of the most necessary works of art I know, a reminder that a civilization that produces the Holocaust may have forfeited its right to ever be at peace again.