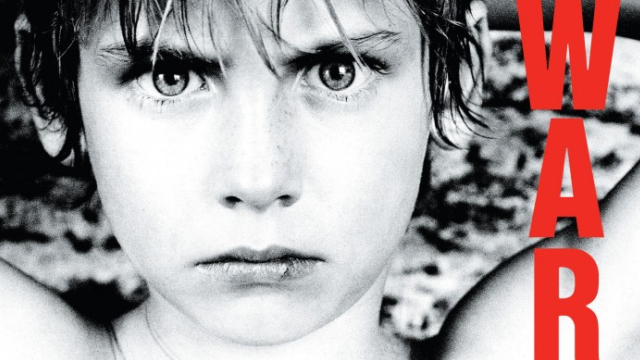

U2 is a band very conscious of its own legacy. This is not the same as having self-awareness – just wait until Rattle and Hum – but that they are able to pinpoint their own changes and evolution, thereby highlighting them for the world to see. It’s why we have seen them “reinvent” themselves on numerous occasions, and how we can separate all their (official) catalogue into trilogies and groups (Infancy, Americana, “Artificial”, Whatever the 2000’s were and the now incomplete Songs of Innocence/Experience pairing). It’s also why on the front cover of War we see the child from front cover of Boy, only here that boy is grown up, standing against a scarred background with the look of battle in his eyes.

This image signifies both an end and beginning for U2. The adolescent innocence of the first two records is fading away, and with War is set to meets its end, to be replaced with strength and maturity. This is very much apparent in the music; War is a forceful record, one coloured with stampeding rhythms and the echoing cries of battle. The guitars here might be dry here and without much effects, but despite this the band cements the sound that would come to define them as performers. The lyrics could seem youthfully idealistic (nicespeak for naïve and corny), but their iconography replaces any of that with an infectious, deserved rage. War, apart from being one of the band’s best albums, is easily their tightest record, ten tracks whose long-lasting impression is brute force, but which stills provides a sense of variety. This is where U2 plays different styles, instead of different styles playing U2.

As a member of the Larry Mullen Appreciation Society, I would stress that much of the primal urgency comes from the drums. Not just in that many tracks starts with percussion, but that most tracks have both a sense of militaristic strength and precision, felt from the very introductory sounds to War in the classic U2 songs “Sunday Bloody Sunday.” Here Edge’s chords are mournful yet full of ire, Clayton’s bass is almost as forceful as the drums, and Bono’s voice reaches those promised levels of grandiosity, befitting his cries in hopes of ending The Troubles. This track was also fortunate enough for some textured violin playing from Steve Wickham, who happened to turn up to the studio one day and ask if they wanted any kind of work. This continuing amount of luck would go on to be a big reason for this record’s variety.

The drums similarly march on in “Seconds,” a funky song that equates the act of dancing to nuclear war, a reference to the Trouble Funk song “Drop the Bomb”, and also something Prince was referencing around the same time. There is a noted hypnotic quality to this track, mostly from that bouncy bassline that Clayton just constantly rides like General Kong rides the bomb, but also in the way the song stops momentarily to play a snippet from the documentary on women in the military Solider Girls. “New Year’s Day” goes back to being more direct, with almost religious odes to “begin again” and “under a blood red sky/crowds gather” that Bono sings in support of Polish Solidarity (the latter image being fitting enough that they named their first live album after it) as Edge plays his guitar both shrieking and scattershot. Sonically, it sounds like a progressed version of the piano sounds coming from October, only here that instrument enhances the sound of the rock band as opposed to overpowering it.

Continuing with their rage, U2 then points that attitude towards those critical against their perceived sincerity and worthiness. Like a lot of “haters” songs, its riposte intent isn’t always matched with the music, but although it might be the weakest track on the album songwise it still some great indignant anger from both Bono and Edge’s guitars. But instead of ending the first half with a perceived bang, U2 instead punctuate Side One with a more experimental track in “Drowning Man.” A tribute in style to the (still underrated) Comsat Angels, the violins return alongside an atypical jingle-jangle guitar sound to a great spacy effect, with Bono’s images of drowning expanding on those from Boy’s “The Ocean”, and would be imagery he would go on to explore in subsequent albums.

Side Two begins with one of my favourite tracks from the album, and the only one not to be produced by Steve Lillywhite (that honour instead went to Bill Whelan). That would be “Refugee,” a bizarre filtering of disco sounds and “My Sharona” whose tribal calls of “War” and “She’s a refugee” are on the good side of ridiculous. The percussion from tingling cowbells (*Christopher Walken reference*) to primordial bangs of toms, and the guitars move to a true sense of elegance in the chorus.

After that the band moves away from overt political statements to make way for ze ladies. But moving away from the general theme of the album doesn’t take away from the fact that “Two Hearts Beats As One” is a kickass song, if only for that propulsive rhythm section from Mullen and Clayton in particular. Bono also brings up his end of the deal, trading the confidence of most of the record for the appearance of lack of confidence and humility (““If I’m a fool for you, that’s something”). “Red Light” is also about a lady, but this definitely in the different context, that of prostitution. Likely U2’s riff on the iconic Police song “Roxanne” (a band for whom U2 were very much fans), the band trade that songs simplicity for this song’s multi-layered declaration of love, including female vocals and a trumpet outro from the band Kid Creole and the Coconuts who just happened to be in Dublin at the time (although somewhat superfluous, this does give this track a nice and distinctive jazzy vibe).

The album ends with a spacious feeling on War’s two closing tracks. The long notes of guitar in “Surrender” cry out for such, as the Coconuts also lend their voices to this track and give it a sense of being haunted, like they are the victims of the fiery city. This is a good penultimate track, but Larry Bono and Edge were right to think that it needed one more to close it. So as “Surrender” fades out, giving the illusion of the end, the “record” restarts and gives the short and fitting round-off of “40”. The harmonies on this finale, as well as the restarting gimmick, give it a Beatlesque on occasion, though if I’m honest they are meant to replicate the tones of gospel, the song itself adapting its lyrics from the Bible’s Psalm 40. You do have to wonder how Clayton, noted atheist, felt about the rest of the band ending the record with a newly record song based on the Psalm only after he left. Still, it makes sense as a means to tie up the record, answering the question “How long do we sing this song?” with the final echoes of singing a new one.

War with all its grand ambitions and even grander sound is where most people point to when they declare U2 had fully grasped their unique sound, and I don’t disagree. Even the datedness of some of its topics do not take away from its energy, its consistency, it hard rock edge (heh heh), and its ability to make thousands chant in unison. But as mentioned in the intro, U2 were aware of their image, and now aware of themselves as an arena rock band shouting slogans. Not wanting to be pigeonholed into that, they went looking and found something else to…fire their passions. Sorry, not sorry…

What did you think, though?

U2 Album Rankings

- War

- Boy

- October