Just as I said that it is tempting to claim that the aesthetic seeds of Tom Wait’s post Asylum work lay in those earlier records when they aren’t really there (though I am mainly thinking of pre Nighthawks at the Diner Waits), it is equally tempting to imply that the transition between those two Waits was completely sudden. Waits’ last two Asylum records, however, demonstrate how much he was willing to experiment, or at the very least felt constrained by what was expected of him.

Blue Valentine demonstrated a gravitation to rock and blues instruments, as well as a larger focus on rhythm, and that focus is refined with a greater emphasis on rock in Heartattack and Vine. Pianos and acoustic basses are replaced with electric guitars and organs (though Tom could never really escape the ballads). There is an indication here that Tom was starting to run out of material for the Asylum, one on this album actually having been written for a movie, but if Tom was sick of his label he wasn’t going to go out limp. Heartattack and Vine has some of Waits greatest moments as a pure songwriter, and purest as a great composer.

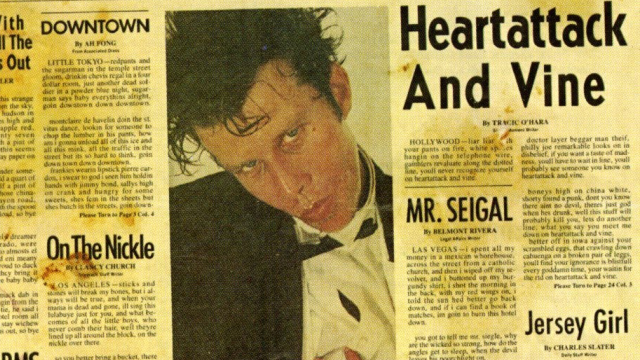

The album begins with the title track, with Tom Waits getting his Howling Wolf on as the organ provides the only thing on the song that isn’t rough. Tom’s voice, the saxophones, the guitars, all rougher than a sandpaper suppository, though the lyrics are surprisingly childlike with reference to old playground chant, though youth plays an important part of this song with the first references to the “jersey girl.” There is also the fantatic line “don’t you know there ain’t/ no devil, there’s just god when he’s drunk,” a philosophy that would definitely follow in future Waits songs. The next number, “In Shades,” is a live instrumental, though forgive me when I say Nighthawks at the Diner makes m unnecessarily suspicious at how live this is. But it doesn’t matter when we get some blues rock as good as this, with some great instrumental stabs and time for both guitar and organ solos.

“Saving All My Love For You” beginning is particularly interesting, with four rings of the church bell before the tones change and it feels like we are in some sleep deprived mumble/dream sequence. The nostalgia found on this track harkens back to feelings on Blue Valentine, ones of Bukowskian vulnerability and depravity than combines with the lush instrumental that creates something both grand and personal. The next song, by contrast, focuses primarily on the town with a grounded rock sound accompanied with funky organs. “Downtown” has some similar themes to “Walk on the Wild Side,” with the people of this city no adherence to gender norms, though I don’t think the latter could have been the theme song to a cool seventies cop show.

Side One ends with the Tom Waits song you may mainly know as a Bruce Springsteen song. I’m gonna have to be a coward however and give no particular preference, as both shape it to their own personalities. Though, as we have already covered, Waits’ automobile songs definitely do have a thematic similarity with the Boss. It should also be noted that this was the first Tom Waits song to be a co-collaboration with Kathleen Brennan, a woman who would have a huge effect on Wait’s future sound, but does exemplify some change in Waits here with glockenspiels and choruses appealing outward to audience singalongs (a “sha la la” song would put it). All this together though makes this one of Waits’ most emotionally sensitive songs, one that seems to have a much happier and content character, though I do wonder if that “can’t sleep at night” claim at the end seems to indicate otherwise.

The opener to the second side of Heartattack and Vine returns to some mighty fine Blues Rock with with the fiscally responsible “’Til the Money Runs Out,” riding the line between the formal and the crazy with images like men in ties swinging from the rafters. “On the Nickel” definitely sounds the least like any track on the album, and that was probably because it is from the movie from the same name (full disclosure, I have not seen the movie). But it definitely has some connecting elements, like references to lullabies and playground chants like in the opening track, and compared to most of the album this is a fantastically soothing track that is like a lullaby in and of itself where it not for King Gruffington’s captivating tones.

Mr. Siegal returns to Blues Rock, albeit one with a more obvious piano influence, and a story of depravity that asks the question “why are the wicked strong.” Well Tom certainly shows his wicked self here, as he coasts on one amazing rhythm, with the occasional abrupt stop to exemplify just how much Tom is not just a singular performer, but a great band leader. And this album ends with a track that is probably on my Top 10 Tom Waits songs, “Ruby’s Arms”. An epic finale in the same way “Tom Traubert Blues” from Small Change was an epic introduction, “Ruby’s Arms” is part-ballad, part-musical, all heartbreaking in its imagery that so bases itself on nature and the wind it could be perceived to be almost ghostly. But with lines like “Jesus Christ this goddamn rain/ will someone put me on a train,” it also demonstrates itself to be disgustingly human.

Heartattack and Vine is full of some of the greatest singular songs in Waits’ entire career, and if I had to choose through personal preferences in music what I would consider to be his greatest Asylum record, it would be this one (followed shortly by Small Change). Lots of people seemed to have this opinion to, as it was the highest charting Waits album and would be for another 20 years). For Asylum, however, that still wasn’t enough. Many years of cult status had not translated to much for the record company, and so as a result Tom Waits was let out of the Asylum.

And next he would make music that sounded like it.

Tom Waits’ Album Ranking

- Heartattack and Vine

- Small Change

- Blue Valentine

- Nighthawks at the Diner

- Closing Time

- The Heart of Saturday Night

- Foreign Affairs