How do you even begin to talk about In Utero without at least mentioning the unavoidable? So here it is: a little over six months after the release of Nirvana’s third and final studio album, Kurt Cobain took his own life in his home in Seattle. So naturally this casts a pall over the record. The tendency to read artistic output as a suicide note is an alluring one even as it reinforces a dangerous romanticism around pain and mental illness, and it was relatively easy for me to avoid when discussing Closer back when we covered Joy Division. But In Utero‘s a different story, not just because I’m much closer to Nirvana than I’ve ever been (and probably ever will be) to Joy Division but also because this is an album that positively baits that sort of reading.

Part of that baiting is undeniably just a hazard of the record’s tragic aftermath. Lines like the ones that open the album (“Teenage angst has paid off well; now I’m bored and old”) shade what was in all likelihood a commentary on Cobain’s constant uneasiness with the business of the mainstream record industry with an unintended shadow of mortality. But then there are songs like “Milk It.” “I am my own parasite,” the song begins. “Look on the bright side is suicide,” it later says. To psychoanalyze Cobain further than to merely note his misery throughout this album would be not just silly and disrespectful but also a slap to the face of every other member of Nirvana who helped to contribute to this album’s chaffed, bleeding emotional registry. But make no mistake: Kurt Cobain is miserable on In Utero.

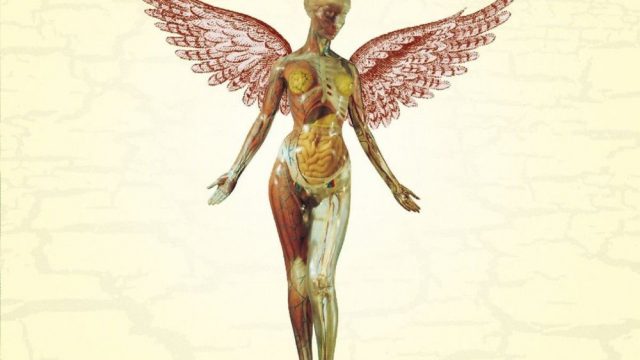

A very large part of the narrative of Nirvana as a whole and Cobain in particular is the extent to which the group and the man were consumed by a greedy public, both captialistically with the sale of albums and radio plays and emotionally with the corrosive psychological effects of fame and public adoration. “You can’t fire me, ’cause I quit,” goes the album’s second and most bracing track, “Scentless Apprentice,” and that’s definitely one way to look at Nirvana’s arc: a band increasingly fed up with the corporate and public demands. In Utero feels (and the cover art does nothing to ease this impression) like a cut of flesh offered as a sort of sacrifice to the band’s obligations before an act of rebellion, and in this sense, there’s a real discomfort to listening to the album for me. Here is this album, bruised and bloodied and fierce, an emotional purge that indicts the way artists and artistic statements are cut up for mass production, and we go and buy it and share in that purge however briefly before we flip it off and move easily to the next art object we’ve bought to consume. Put another way: my copy of In Utero came from a Best Buy, and I’m sure yours came from somewhere pretty similar. “Radio Friendly Unit Shifter,” the most obvious record-industry critique on the record, says, “Use just once and destroy” (after a cheeky spoken cue of “Moderate rock!”). I have definitely used In Utero more than once, but even then, there’s still that queasy word: use. The central indiscretion of art is its ability to use sincere and vital emotions for individuals with nowhere near the stake in those emotions, and the raw primal scream of In Utero makes that feel even more acutely indiscreet. Obviously, the record industry did not kill Kurt Cobain. But the fact that he’s dead gives the ethics of listening to their music just hazy enough to be uncomfortable.

It’s Nirvana’s best album, of course, and probably the most Nirvana album as well. Everything people ascribe to the band is here: melodicism (“All Apologies”), noise (“tourette’s”), angst (“Dumb”), sludge (“Milk It”), irony (“Radio Friendly Unit Shifter”), grunge anthem (“Heart-Shaped Box”), loud-soft dynamics (“Pennyroyal Tea”). Anyone who’s been listening to Nirvana since Bleach is going to recognize everything on In Utero, but what makes this album so head-and-shoulders above the groups other efforts is how each of those sounds hits the ground with greater refinement than ever before. The sludge is sludgier, the noise is noisier, the melodicism is as sweet and melancholy as any band ever, and “Heart-Shaped Box” is one of the best radio smash singles of the era. And moreover, it all works great together as a whole. As much of a greatest hits of Nirvana sounds In Utero can be, it’s cohesive within that diversity in a way no other Nirvana record is. When I say that this is their best album, I do mean album. On a song-by-song basis, it’s not hard to call out this record (especially in relation to the wall-to-wall banging Nevermind) as having “filler”: “tourette’s” and “Very Ape” come to mind readily as tracks that could have been cut. But in terms of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts, In Utero is unparalleled among Nirvana’s discography. The whole thing just hangs together, and by the final, heartbreakingly peaceful closing notes of “All Apologies,” there’s no doubt, ethical quandaries and all, that you’ve just experienced a statement.

“What else should I say?” Cobain asks minutes before the album halts. The question goes unanswered.