As a statement it’s great, as a giant FUCK YOU it shows integrity–a sick, twisted, dunced-out, malevolent, perverted, psychopathic integrity, but integrity nevertheless, to say this is what I think of you and this is how I feel right now and if you don’t like it too bad. (Lester Bangs on Metal Machine Music)

Lou Reed released 64 minutes and four seconds of layered guitar feedback as the double album Metal Machine Music (16’ 01’’ per side) in the year of the American Bicentennial. A lot has been written on the essential fuckyouhood of that act, some by Reed (who claimed at the time that he’d layered classical melodies in it, something he later said was a, what’s the word, lie. Methedrine’s a helluva drug), some by critics (Renaldo Migaldi called it “one very big, and very necessary, creative vomit–Lou was puking up the bones of the cartoon character into which he’d transformed himself”) but Bangs and a very few others also appreciated it as a great hourlong work of sound. I’m one of them, and Metal Machine Music serves as a good Gateway to the world of what’s sometimes called “noise music” and what I’ll call just good ol’ noise.

I’ll start with some distinctions, if not quite a definition. By noise I don’t mean “stuff that sounds bad”; it’s a classification, not a judgment. Nor do I mean “music of great complexity”; two of the greatest figures of contemporary music, Elliott Carter and Ornette Coleman, wrote and performed music of amazing density and polyrhythmic complexity (so did Reed and the Velvet Underground on “Sister Ray”), stuff that’s near-impossible to untangle after a dozen listenings, but neither of them created noise. Both of them created works that have many different lines of sound moving against and with and through each other and interacting, but it’s not noise; if you can watch and understand a football game (with nearly thirty people on the field interacting), you can understand their music. Listening to noise, though, is closer to watching a crowd. Actually it’s closer to being caught in a crowd.

Music, no matter whether it’s a single instrument or a hundred, consists of a sound played against a background. John Cage’s 4’33’’, where a performer plays nothing for that period of time, was Cage’s attempt to get listeners to pay attention to that background, to the ambient sound of wherever they were, and to hear that as music. (The John Cage website provides an app where you can record 4’33’’ of ambient sound and upload it.) Noise is not a background heard as music, and noise is not a sound played against a background. Noise is a background that overwhelms all other sound. Like Ambient music, noise is an environment but one that reverses Brian Eno’s definition: rather than music that “must be as ignorable as it is interesting,” noise cannot be ignored at any volume. (That’s why it’s my ringtone.) It’s a cool historical coincidence that Metal Machine Music and Eno’s masterwork Discreet Music were released within a year of each other.

The power of noise has a lot in common with the power of modern painting; both move away from being about anything and move towards dominating a piece of time or space. The works of Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Philip Guston, Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly can’t be ignored, and they almost go past the question of “are they good or bad?” Like noise, and like the monuments of nature, they’re there, and one doesn’t really “appreciate” them. “Appreciation” is a domestic and domesticating process. Viewers appreciate; noise dominates. In the first sentence, the viewer is the subject; in the second sentence, the work is the subject. After a good noise work, listening to music can feel like coming back to a great Impressionist painting after an afternoon of looking at Pollocks–it’s nice and all, but it’s not powerful. You can look away, and noise never gives you that chance.

Because noise doesn’t operate the way music does, it needs to be constructed according to principles different than music. Noise has to be considered according to its totality and presence rather than the individual lines; Mark Prendergrast, in The Ambient Century, argues that Gustav Mahler is the founding point for this kind of musical thinking, something I pursued in this essay. In Metal Machine Music, Reed does something that many noise composers do: the left and right channels are independent of each other, both generating their own noise. Reed also has a good sense here of how to vary the density and volume of the sound; noise that’s unignorable but also boring is just the worst. He employs a lot of hard tape cuts, too; the environment here isn’t just shifting but continually and unpredictably changing.

As Cage noted, many of the twentieth century’s classical composers became concerned with “sound come into its own,” and many of them moved towards noise. In my definition, there’s a difference between using noise as part of musical composition and a noise composition; Cage nicely makes that distinction when he described Edgard Varèse as the composer “who fathered noise into twentieth-century music.” (Specifically, Varèse’s percussion piece Ionization, with a bunch of unpitched drums and a siren, did that.) There are also a lot of noise compositions that use musical elements, and Cage, Krzysztof Penderecki, and Gyorgy Ligeti made some of the best-known. The term “sound-mass” describes their works; they are not concerned with individual musical lines but the effect of the sound as a whole. The result can be something that’s musical (as in Ligeti’s Lux Aeterna) or noisy (as in Penderecki’s Polymorphia); which one depends on the density of the sound and the amount of recognizable pitches present, and it probably depends on the perception of the listener as well. (For a further discussion of this, check out this podcast, especially the section on The Shining.)

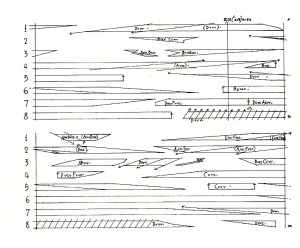

Another work, Cage’s Williams Mix, achieves noisehood through speed rather than density; it’s a collage of sounds recorded on eight tapes (played simultaneously) and spliced together. Cage remarked that when making it “a second, which we had always thought was a relatively short space of time, became fifteen inches [of tape.]” The score is simply a chart (Cage called it a “dressmaker’s pattern”) showing how the eight tapes are to be cut and assembled. The score is 192 pages, the piece has over 500 sounds in over 3000 events, it took over a year to splice it all together, and it’s just over four minutes long:

Another work, Cage’s Williams Mix, achieves noisehood through speed rather than density; it’s a collage of sounds recorded on eight tapes (played simultaneously) and spliced together. Cage remarked that when making it “a second, which we had always thought was a relatively short space of time, became fifteen inches [of tape.]” The score is simply a chart (Cage called it a “dressmaker’s pattern”) showing how the eight tapes are to be cut and assembled. The score is 192 pages, the piece has over 500 sounds in over 3000 events, it took over a year to splice it all together, and it’s just over four minutes long:

Probably the composer who went the farthest into noise was Iannis Xenakis. Godard sez that great art “is algebra and fire”; Xenakis’ music is group theory and nuclear reactions, and the group theory part is not a metaphor. After getting half his face blown up and an eye taken out in WW2, Xenakis went to work as an architect and developed several works of music according to the same principles as his buildings. From the beginning, he worked with the totality of sound produced, by whatever means, and used mathematics to develop his pieces in the same way other composers would use the rules of harmony. He described a lot of these methods in his treatise Formalized Music, an exhausting but necessary read.

For whatever reason–getting blown up, the commitment to mathematics, his feeling that he was “an ancient Greek living in the twentieth century”–Xenakis’ music fucking owns, it’s confrontational, demanding, and rewarding. I think his success at noise comes from the way he treated music as sound from the very beginning of his career, unlike a lot of other composers like Penderecki, Ligeti, and Cage who were musicians first and noise artists second. All three of them, by the way, didn’t keep going into noise but moved back into music. Xenakis kept going; probably the beginning of his work in noise was in 1958 with the brief tape piece Concret PH, built up from one-second recordings of fire, a noise work from a single element:

He continued with orchestral works (Metastasis, Pithoprakta) that built up sound using random processes, much more elaborate ones than Cage ever did. He created works for electronics, tapes, and hybrid orchestral-electronic compositions (Hibiki-Hana-Ma, Kraanerg); in many of his works, Xenakis has music coming from eight or more speakers, dominating not just time but space too. His The Legend of Er, a forty-minute slab of sound, is one of the most monumental things I’ve ever heard. It has the greatest opening in the history of music (a single tone dividing and transforming) and sounds like being present at the birth of the universe. Words like “beautiful” or “moving” or any kind of humanistic judgments have no place for sound like this; I’m not moved by them so much as humbled.

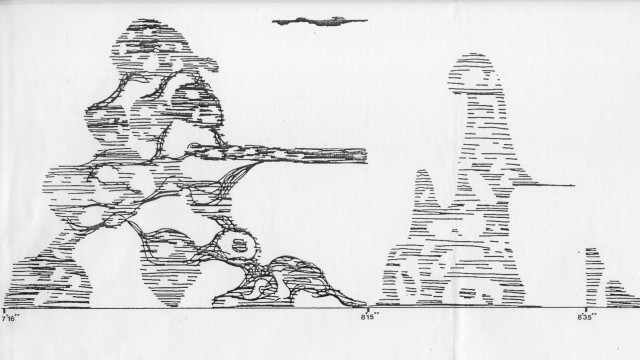

Xenakis went farther than just creating noise works; in the late 1970s, he developed the UPIC computer system to produce them. (In the 1990s, he would create another system, GENDYN, that produced both the structure of the sound and of the composition entire.) In a UPIC piece, the composer draws a plot of frequency (vertical axis) against time (horizontal axis) and the computer produces the sound from that. Xenakis’ first work on the system was Mycenae-Alpha; that’s an excerpt from (what I guess we should call) the score up top, and here’s the sound produced from it:

UPIC is ideal for noise and terrible for music. (Composers have used it for entire pieces and to add noise to musical works; check out the compilation CCMIX: New Electroacoustic Music from Paris for some of them.) Acoustically, what distinguishes notes from noise is that notes come from a specific, exact set of frequencies and noise comes from a messy range of frequencies. On UPIC, a musical note could only be produced by a set of precisely spaced, infinitely thin lines. UPIC, though, makes all the parameters of a noise composition clear and visible–the density, range, rhythm, and volume of the sound.

The appeal of noise is in part its sheer physical force. Writing about noise, the metaphors invoked are all from the physical world–weight, energy, mass, presence, force–rather than the emotional or aesthetic worlds of most music writing. Regarding noise as a unified object, it makes sense that noise composers have methods–Xenakis’ UPIC, Cage’s tape-splicing–by which they physically shape the sound rather than “hear” it, or compose it. Noise appeals to an almost philosophical conception of sound, not as a form of expression, not as something made by people, but as something with its own being. It’s not for everyone, but for the curious, Metal Machine Music is a fine place to start.