Mary, the dress-waving vision from “Thunder Road,” looks the song’s starry-eyed narrator and his dreams of wing-wheeled freedom square on and says, “No.”

This, Bruce Springsteen posits, is what happens on the title track to his 1978 Born to Run follow-up, Darkness on the Edge of Town. “That blood, it never burned in her veins; now I hear she’s got a house up in Fairview and a style she’s trying to maintain,” sings his main character with resentful ambivalence. He adds, perhaps trying to be callous but betrayed by the impassioned vocals and E-Street-Band crescendo, “Well, if she wants to see me, you can tell her that I’m easily found.” Alone now, he lives in the city’s bleak vanguard while the woman he loves lives a hollow pretension that’s everything he wanted to reject, his isolation and her propriety driving him further into his addiction for that self-destruction he used to call “ambition.” The last words we hear from him are, “I’ll pay the cost for wanting the things that can only be found in the darkness on the edge of town,” and there’s no reason to believe that isn’t true and that he’ll just be another ghost haunting the skeleton frames of burned-out Chevrolets, screaming her name at the night.

Or:

Mary says, “Yes,” and off into the sunset she rides with her grinning idealist. Years later, she lives haggard, worn to the bone from her man’s relentless drive to race that thunderous road.

This is the reality of “Racing in the Street,” the mournful album centerpiece that closes out Darkness‘s Side One. She is alone again in everything but the letter of the law as she realizes far too late that she is merely a catalyst of his best and worst impulses, a prop to decorate his dreams and to eulogize his failures. “Her pretty dreams are torn,” the narrator understands, but even that’s not enough to keep him from going out again, to continue to crow that “summer’s here, and the time is right for racing in the street.”

Darkness on the Edge of Town is not so much a rebuttal of Born to Run as much as it is an expansion of that album’s universe. The two songs highlighted above are significant in how they represent a broadening of Springsteen’s point of view beyond the youthful masculinity that defined his 1975 landmark. In these songs, the Boss flips the script a bit, giving voice to those outside the narrator and particularly to the women with whom he comes in contact. They are no longer abstract muses, pretty things to dance with and sweep off their feet; they ache and grow and live with that same human vulnerability as any of Springsteen’s dreamers. Candy, of “Candy’s Room,” tells the presumably masculine narrator that “if you want to be wild, you got a lot to learn,” lampshading both the naivety of Bruce’s stock male and the previously unexplored desires of his stock female–desires, it’s worth noting, likely to crumple in the long term. “The broken hearts stand as the price you’ve gotta pay,” we hear on the album-opening “Badlands,” and this is exactly it: to be that dreamer, you are faced with a tolling duality: to either crush others on your way to your dreams or be crushed yourself. With the women of Darkness, it’s the casual misogyny in the dreaming that suddenly becomes evident. Long-term, somebody always loses.

This is an album marinated in the long term. Born to Run is, with a few exceptions, and album of the present, the delicious possibilities of being on the razor’s edge of a decision. On Darkness, decisions have been made and time has passed (sometimes even generations, as in the father-to-son narrative, “Adam Raised a Cain”). With time comes a wider lens, by necessity, and it’s through that wider lens that we can see that “Born to Run” ideology as a pathology as much as a dream. “Badlands” again: “A king ain’t satisfied ’til he rules everything.” And if you never rule anything, as it becomes clear that, over the long years, these characters will not, you keep grasping for it anyway until everything else in your life has withered from neglect. That long view also lays bare the rigidity of American society, where, as the title track argues, “some folks are born into a good life” and “other folks get it any way, any how.” The quest to rule everything is a cruel, fatalistic irony within a world that seems to predestine social strata from birth.

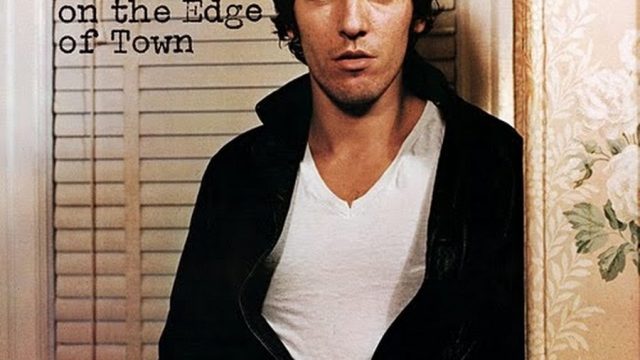

These ideas aren’t new to this album–“Jungleland” and “Backstreets” both examine them even within the romanticism of Born to Run‘s maximalism. But up to this point, they have never been so piercing or so raw. Born to Run, even at its most tragic, is widescreen Cinemascope; Darkness on the Edge of Town is grainy, handheld camerawork, capturing wounds that Springsteen’s previous work never got close enough to detect. This effect is, no doubt, helped by the relatively spare arrangements when compared to the full-band tidal wave of sound on the rest of the post-E Street Shuffle work. The production on Darkness is dry and hard-rock-oriented, filled with nervy, aggressive guitar work and much less prone to grandiose Clarence Clemons solos. As such, it’s an album that feels like it takes the limitations of the Born to Run worldview with a boots-on-the-ground seriousness and a much more acute awareness of how those limitations work into the traps of larger societal machinations and ills. This makes it the most philosophically important of the Boss’s ’70s albums as Bruce approached his trio of early ’80s albums that represent the most cynical and world-weary work of his entire career.

It’s not all gloom, though (we aren’t there yet), and that’s ultimately what helps make it great. As I said, this is not a rebuttal so much as an expansion, and the empathetic affection for these characters desperate enough to dream remains, most effectively in “The Promised Land,” where Bruce’s protagonist sings with beautiful conviction, “I believe in a promised land.” No irony or condemnation: just a simple affirmation of one of the deepest, most universal human desires. In the face of the moral complexity and bleak future that pervades the rest of the album, that desire cuts even deeper here.