Bruce Springsteen famously described the opening snare of Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” as “sound[ing] like somebody’d kicked open the door to your mind.” So it’s only appropriate that Springsteen’s very own “Like a Rolling Stone,” the magnificent, no-holds-barred “Thunder Road,” begins with the opposite: the slamming of a screen door. The waving of a dress, the sounds of classic yearning, the heartfelt pleas of the young, and before you know it, we’re trading in wings for wheels; the night’s busting open, and these two lanes can take us anywhere. And they do. Later on, in the record’s title track, this promise is fulfilled as Springsteen recounts a highway “jammed with broken heroes on a last chance power drive.” One might cynically assume one of them is Dylan’s own Princess on a Steeple, scrounging her next meal.

But Bruce doesn’t.

Dylan’s musical progressivism belies his conservative contempt for ambition in its lyrics, a disdain for those who think of themselves as more than they are, but on Born to Run, it’s the opposite: the music is looking backward at the old status quo, a nostalgia for the sounds of classic rock and roll (albeit hyped up on mid-’70s arena production–the Roy Orbison allusion in “Thunder Road” is no accident, nor are the album’s very 1950s-by-way-of-American–Graffiti car obsessions), but the lyrics are a giant, sloppy hug for the people who want to be bigger than their station, the people who have the arrogance to see their home as “a town full of losers” and then have the stones to up and leave. These are Springsteen’s ambitious ones, not connivers and dilettantes but the material expressions of the best of the American Dream. And so is Springsteen himself; Born to Run is the sound of ecstatic ambition from a guy once compared to rock’s most noted cynic, coming of age as rock’s greatest Romanticist.

It’s fantasy, of course, that’s he’s peddling–a rich, mythic, and altogether beautiful fantasy lifted on the arrangements of the fully come-into-its-own E Street Band, but a fantasy nonetheless. And Springsteen knows it, too (and would more keenly know it in the increasingly curdled releases following this one), and that awareness is what keeps that fantasy from being the head-in-the-sand kind. Acute pain and desperation animates these songs. The album’s eight tracks sketch characters who, for all their ambition and optimism, are frustrated and exhausted and even miserable within their current lives, and it’s this misery that leads them to their outsized boasts of better futures. But even these futures don’t unequivocally promise freedom from darkness: the highway is jammed, let’s not forget, a detail from the same song that also calls those freedom-bestowing vehicles “suicide machines.” “Thunder Road” ends with a parade of ghosts and “skeleton frames of burned-out Chevrolets.” The dusky “Meeting Across the River” leaves its protagonist on a bleeding edge of ambiguity, his as-yet unfulfilled assertions that “tonight’s gonna be everything that [he] said” haunted by the doubt of Randy Becker’s lonely trumpet.

And then there are the two moments of overt tragedy: “Backstreets” and “Jungleland,” both of which close out their respective LP sides, leaving the tang of their stories to linger like black coffee: “Backstreets” with its tale of a doomed friendship that looks for transcendence but is instead marooned with the stark isolation of the fact that “we’re just like all the rest, stranded in the park and forced to confess to hiding;” “Jungleland” with its panoramic saga of street gangs “in a death waltz between what’s flesh and what’s fantasy.”

But even then, in the record’s darkest corners, the myth continues. This is not despair or nihilism; anger is conspicuously absent from each of the album’s 40 minutes. There is never any doubt that meaning and transcendence exist; it’s, at its worst, just out of reach, sure to be grasped at the next swing of the arm. Even if the lyrics form these characters as destitute and unlucky, the arena grandeur of the E Street Band’s pianos and saxes and horns and drums never leave them on the ground, and within that aesthetic joy is the surest sign of of hope, of relief, of freedom, of God that there is. At the very last word of “Jungleland” and of the album itself, the humans of the street wounded and defeated, the phonetics of the song’s final lyric fall away into the purity of the moment’s emotion as Bruce looses into the air a wordless wail that ranks among music’s finest sounds, at first alone and abandoned but then joined by the band swelling beneath him until they, together, soar into something incomprehensible, the intangible intersection between “flesh and fantasy,” music and meaning, whose weight language can’t bear.

It’s not the opening that kicks open the door. It’s the end. That grand destination hinted at, longed for, darted after with impulse and self-destructive abandon. And that wordless note of Springsteen’s voice calls us there.

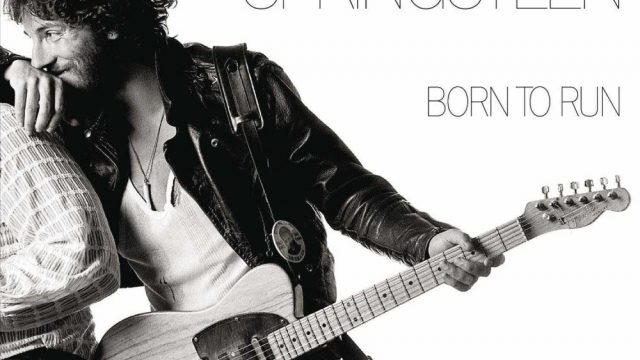

I’ve commented in my reviews of earlier Springsteen albums that it’s hard to look at those first two records in the context of the rest of the Boss’s career without feeling that they, while perfectly fine on their own, are a bit underdeveloped and thin compared to what Bruce would eventually be known for. Not so with Born to Run. Born to Run is Bruce Springsteen; this is what he’s known for; this is what he accomplished (or at least the beginning of it). When you ask someone on the street about Bruce Springsteen, it’s that slamming screen door, the jammed highway, the transcendent wail of “Jungleland” that immediately comes to that person’s mind. Bruce Springsteen would go on to make many more masterpieces, sometimes of equal value to what’s here. But never has he surpassed the wide-eyed grandeur of this third album. And never will he. Because it’s damn perfect.