The following is a slightly extended version (thanks to a revelation by Rosy Fingers that I’d glossed over) of my 2018 Summer movie gift from ZoeZ. It’s one of my favorite pieces, and the most effortless, that I’ve written here, and I’d like to give it a more prominent showcase. — Son of Griff

Paterson is the last name of the protagonist of this movie. The character lives in Paterson, N.J., where he works as a bus driver. He also writes poetry. His favorite poet is William Carlos Williams, who also lived in Paterson, and wrote a five-volume length poem by that name. Williams is not the only famous person from Paterson. The film lets us know that Lou Costello, and Ruben “Hurricane” Carter also hailed from there. Paterson, the protagonist, will not become famous, at least as a poet, for, unlike his inspiration, he writes his verses, privately, in a secret notebook, not sharing them with anyone, not even his spouse.

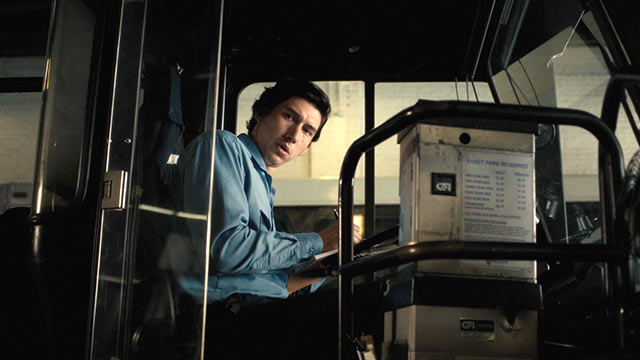

Paterson covers a week in Paterson, the bus driver’s, life. His days, seven depicted in the movie, exhibit repetitive patterns of behavior. He wakes up next to his wife every morning, who tells him her dreams. He walks the same route to work each day, strolling past an abandoned factory. He writes a little in his bus before a colleague comes to the door to tell him of all the shitty things that are happening in his life. He drives his route, overhearing conversations taking place among the passengers. He stops by a waterfall to write some more during his lunch break. He walks home past the factory. Upon arriving he collects the mail, always straightening the mailbox that, for some reason, gets tiled daily on a precarious angle. He has dinner, observing how his wife has painted black and white patterns on her clothes, the shower curtain and the window blinds. She starts learning to play a harlequin painted guitar. She also frosts these patterns on the cupcakes that she bakes for the farmer’s market. Unlike Paterson and his poems, she wants to gift her cupcakes to the world.

Paterson ends his evening by taking his wife’s bulldog for a walk. He ties it up outside of a local bar every night, where he talks to the bartender, although it’s more like the bartender talks to him. The bartender tapes pictures of famous events and people from Paterson, the city, on the wall behind the bar. Lou Costello and Ruben “Hurricane” Carter are on the wall. Other people show up and talk to the bartender about their problems every night. Paterson orders one beer, and when he looks at the glass, half empty, the image of the glass fades to black. The day is over. Time to reset.

Paterson boasts a structure built on scenes of repetitive daily rituals, and variations of encounters within those patterns. When Paterson’s wife dreams of having twins, conversations he has or overhears start having doubles. At the bar, everyone has troubles, but it’s different people, with different problems, every night. When the weekend comes, these patterns will loosen, gradually pushing the narrative from a circular to a more linear direction. A promise Paterson makes to copy the poems on his day off goes unfulfilled. The couple goes out to a black and white movie instead of staying in and having Paterson walk the dog. There are consequences.

Paterson’s past also creeps into his present. His time in the military is signaled by a photograph by his bedside. His competence emerges in handling various crises with hitherto unforeseen skills. He calms down a busload of passengers when the bus he drives malfunctions with determination and empathy. He disarms a romantically disgruntled customer with judo-like aplomb. He is a man unto himself, but also the right man for his place and time.

Kind of like this movie.

Jim Jarmusch has made films like this before. The Limits of Control constructed a narrative within the espionage genre that riffed on ritualized patterns of behavior. Before that, he made a series of short films about conversations people have while drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes. I liked this one better. In some of the earlier films the formalism of Jarmusch’s screenplays overshadows the inherent dramatic potential of the story. His characters ossify under the director’s formalist gaze, rendering them passive, unable to act outside of a pattern they were assigned. Paterson avoids this, thanks largely to Adam Driver subtlety conveying his character’s clamped down emotional state while projecting interest and concern to those in his orbit.

While he doesn’t express his own feelings explicitly to his wife, friends, or passengers, he responds warmly to their words, even displaying the qualities of leadership, and bravery when they are in danger or seeking encouragement. At the end he incurs a loss in which he has no one else to turn. However, by simply being present, in the physical space of The Great Falls of the Passaic River, he receives a benediction, born of a connection that poetry makes beyond borders, beyond self. Paterson is a city. Paterson is a man, and in the end, they are the same.