The opening title card of Bringing Out the Dead reminds viewers that it takes place in the early 1990s and not 1999 when the film was released. By that time pop culture’s dominant representation of New York City as a drug and gang infested dystopia had given way to a Disneyfied Times Square scored to Frank Sinatra. Upon its release, the movie often felt like it had missed the opportunity to address the urban despair at the twilight of the Reagan/Bush era. In 2020, as the world enters a potential depression propelled by a catastrophic health crisis, it now seems shockingly relevant.

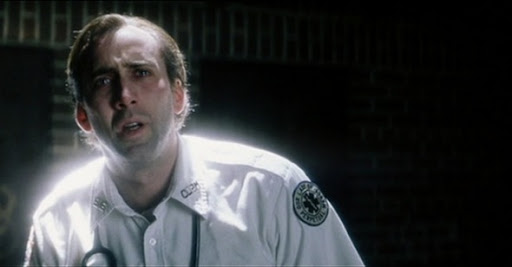

But only to a point. As we watch EMT specialist Frank Pierce (Nicholas Cage) ride down Hell’s Kitchen’s mean streets over three nights, one senses that the city he observes isn’t exactly New York. There are hot white flashes piercing the gloom, and the street people shuffle with a phantom-like evasiveness, which is appropriate since Frank sees them as ghosts, the most notable specter being that of a 14-year-old girl he failed to revive on a run 6 months earlier. Since then he hasn’t retrieved one soul from the great beyond, a failing that denies him the messianic joy of spiritual regeneration amidst the unceasing tide of human suffering. As the protagonist’s voice-over wallows in eternal ennui, the viewer becomes aware that they are not experiencing an immediate flow of sensations but a remembrance of a time when the narrator’s objective perceptions were altered through depression and occasional drug use.

Bringing out the Dead is therefore not an objective report of New York City life, but a highly subjective and expressionistic rendition of its public image at a specific time. With the exception of generally calm moments Pierce shares with Mary Burke (Patricia Arquette), whose father’s cardiac arrest precipitates the film’s moral dilemma, the movie mostly revels in eschatological urban archetypes that fray the narrator’s nerves and test his sanity. He is Dante’s poet navigating the Inferno with the occasional Virgil (in the form of Ving Rhames) to serve as a partially useful interlocutor. Pierce glides through an alternative Manhattan in which the latent potential for violence borne of disorder is ever-present. Mercy sporadically appears, particularly in the tenderness that Mary displays towards Noel, an old friend discarded to the street after a brain injury, but Grace is absent in Frank’s orbit.

While not overtly religious, Frank interprets his relationship to society in Christian metaphors. He sees the homeless as souls angry to have died where they did and who now roam the streets in a purgatorial state of perpetual resentment in which he is the target. In a dream sequence he imagines himself as one who raises, Lazarus like, the bodies of the dead. This informs his notion of progress, as he prioritizes his needs for personal redemption over the suffering of the people he encounters on his job. Through Mary’s struggle with her father’s crisis, as filtered through his own occult perceptions, Frank starts questioning assumptions that life naturally fights to sustain itself, and adjusts his attitude to respond to this new moral insight.

To quote another estimable Martin Scorsese picture, you don’t make up for your sins in the church, you make up for them in the streets. The liminal zone between the living and the dead demands moral actions that contradict the foundation of his profession, as well as the legal strictures governing the society that the audience lives in. At the end, Frank follows the dictates of his addled conscience. In his memory this is an epiphany, a move towards redemption. His choices correspond to the imaginary world he inhabits, not for the moral edification of the audience. Is this a correct choice? That judgement, ultimately, is left to the viewer to decide.