The Solute Canon Series: An exploration of films and other cultural touchstones outside the traditional canons that have frequently influenced and appeared in Solute discussions.

Despite what a certain Dear Leader might believe, Jaws is in the canon. If nothing else, it’s in the Library of Congress, chosen for being “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant,” and it covers all those bases. A classic of horror, a benchmark of blockbuster marketing, a film that has inspired countless imitations. But what of those imitations? Are they worthy of enshrinement?

Somehow, when I first watched Grizzly, I didn’t appreciate how much a rip-off of Jaws it really is. It was filmed in 1976, only a year Jaws redefined boffo box office, and what is a bear if not the shark of the land? The thorough and delightful williamgirdler.com, a website devoted to director William Girdler’s work, says screenwriters David Sheldon and Harvey Flaxman thought the movie would be a “great follow-up” to Spielberg’s shark shocker. It does not go into detail about whether they rewrote Sheldon’s initial story (based on an encounter with a bear while camping!) to mimic the earlier movie. Because there are a lot of similarities.

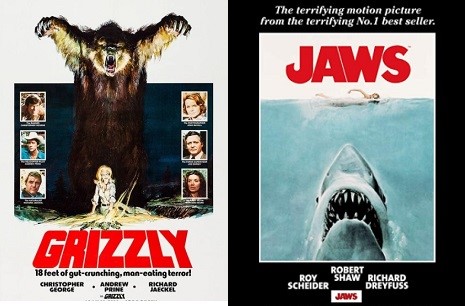

Let’s break down the basics: The beast attacks a natural area dependent on visitors and despite the protestation of the lawman protagonist, the powers-that-be keep the tourist money rolling in and ignore the danger until the death toll reaches a tragic peak. That lawman has allies, a brash and overconfident would-be master of nature and a more laid-back guy who’s comfortable with technology (although it inverts the Jaws dynamic by having the former be a scientist and the latter a military veteran). The beast is not seen in full for much of the movie, although the viewer does see its victims from the perspective of the creature about to chow down, and in the end the monster can only be defeated by being blown the fuck up. Even the extremely boss Neal Adams-illustrated poster draws inspiration from Robert Kastel’s Jaws design (which was inspired by the rather more phallic original book jacket) — a giant bear looms over a nubile young lady, ready to pounce from above as opposed to the enormous shark approaching a naked swimmer from below.

But if the structure is openly swiped, the details differentiate. Instead of Roy Scheider’s family man reluctantly facing his fear of the ocean, Christopher George’s head ranger is mostly just pissy at Joe Dorsey’s greedy park supervisor and his relationship status is one big It’s Complicated, at least going by the monologue where he hits on a spunky photographer by talking about how he acted like a jerk so he could drive his annoying wife to divorce him. The great Richard Jaeckel gets an appropriately Quint-like send-off for his arrogant naturalist, but the fate of the Hooper analogue is more in line with Peter Benchley’s novel than Spielberg’s movie. On the other hand, at this point in his career Spielberg still had the guts to kill children, the whiny moppet we get here is mauled but his mom takes the fatal blow. And on the other other hand (look, this bear leaves a lot of body parts laying around), Spielberg films his naked chick in the dark and with a sadist’s eye to her death; Girdler knows what the people want and it is impossible to improve on Wikipedia’s deadpan summary here: “A female ranger stops for a break at a waterfall. Deciding to soak her feet and finally taking off her clothes and showering in the waterfall, she is unaware that the grizzly bear is lurking under the falls and she is attacked and killed.”

Because this is the real difference — William Girdler is no Stephen Spielberg and isn’t trying to be. The clearest indicator of this is how Spielberg turned special effects difficulty into restraint, holding back showing his shark until the very end. Girdler had an actual bear, Teddy, who generally looks perturbed instead of murderous and is mostly shown in different shots from his human co-stars. His maulings are accomplished by a giant fake bear arm on a stick batting people (mostly women, frequently undressed) bloody. This is never not hilarious, but it’s only the most obviously funny thing about Grizzly. The crummy effects, the stilted dialogue and lousy acting from local Georgians — combine that with lackadaisical pacing that leads to odd bits of nonsense while marking time between kills and boobs and you have all the makings of a riffable classic.

The last time I saw Jaws was a few years ago at the Hollywood Bowl, with a live orchestra playing John Williams’ immortal score and a huge audience gleefully yelling out the movie’s dialogue. People wanted to be part of the movie. Once again, Grizzly is similar to but different from its inspiration. Watching it a week ago, we picked up on random whinnies dubbed in from allegedly off-screen horses and made a lot of hay out of braying our own random “neighs” whenever the movie hit a dull spot. Running gags like that, talking back to characters (“What kind of game is this, bro?” as George seems to neg himself while flirting with the photographer), hooting and hollering at the dopiness on the screen were part of fun. The first time I watched Grizzly, more than a decade ago, I stumbled across it on basic cable one extremely lazy Saturday morning and couldn’t stop watching, and one by one my brothers and my dad got sucked in as well. We were inspired to clown on the movie, to laugh at it instead of with it, but Grizzly was still bringing an audience together.

Which is why I’ve been glad to see Soluters finding and enjoying this over the past few weeks. It’s fun to goof on movies and a movie that’s a known fount of goofery — one that can be referred to and passed around among friends — is something no canon should be without. Grizzly was panned by critics and while it is not good, it is open in its mercenary intent and honestly trying even as it fails in its execution, as opposed to more winking and knowing trash. It was the top-grossing independent movie of 1976, making more than 40 times its budget, and that too speaks to how people can find value, or at least entertainment, in junk. The Library of Congress’ loss is our gain.

![[gargling noise]](https://www.the-solute.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/grizzly1.jpg)