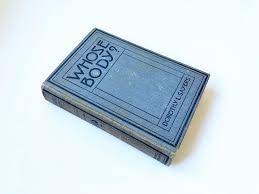

When people discuss twentieth century female British mystery novelists, they talk about Agatha Christie. And that’s, you know, understandable. Christie was incredibly prolific, publishing eighty detective books if you include the fourteen books of short stories. Miss Marple and Hercule Poirot are iconic characters. Christie tops every list of records for fiction—most sold, most translated, longest-running play. All of that. And . . . I don’t read her books. They’re fine, but they’re not my thing. I don’t like her style. I would much rather sit down with a nice Dorothy L. Sayers and her charming but scarred Lord Peter Wimsey.

In this, his first appearance, we initially see him on his way to a book auction. He’s forgotten the catalogue and returns home just in time for a phone call from his mother, the Dowager Duchess of Denver. An architect of tangential association with the family has awakened to the extraordinary circumstance of finding a body in his bathtub, clad only in a pair of pince-nez. Lord Peter sends his manservant, Bunter, to the sale with instructions as to what he particularly hopes to buy and hies himself to Battersea to meet the nervous Thipps and find out what he can about the body in the bath.

Thus begins a complicated tale of financiers, experts in the brain, and two intertwining cases—one of a mysterious appearance and one of a mysterious disappearance. Everyone checks out the obvious question first, but the mysterious appearance and the mysterious disappearance are not the same man and cannot be the same man; how Peter is immediately certain of this has been left out of later releases of the book, but the missing man was initially mentioned to be “a pious Jew of pious parents,” as as the man in the bath “obviously isn’t,” it’s clear they are not the same men. Though a medical student later makes a statement that might be an implication about the same thing of a different body.

Which ought to be our warning that the handling of Jews and Judaism in the book has all the sensitivity of a book written by a middle-class English shiksa born in 1893. By all accounts, the missing Sir Reuben Levy was a good person. Self-made. Kind to his servants as well as his ostensible equals. At one point, he is propositioned by a sex worker—this is all talked around but quite clear—and is so noble that he doesn’t even realize what’s going on. However, it’s also true that certain ethnic slurs are used, and Sir Reuben is the only prominent character who was born Jewish, and he’s missing when the book begins. It’s also assumed, not just in this but every time the subject comes up, that Jews are all in finance in some way and all fit certain personality types. It’s really uncomfortable.

Lord Peter is a fantasy figure. He’s rich. He has impeccable taste. He has an utterly devoted manservant. He is an extremely talented musician, one of the best cricketers in England, and staggeringly brilliant. He is quite strong and a crack shot. He is also, and the book does not shy away from this, mentally ill. Over the years, we will learn the details of his service in World War I and the cause of his PTSD, but even in this first book, he shows symptoms of his illness. In The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club, we’ll see a World War I veteran left considerably worse off, in every sense, than Peter, but he’s still not a well man.

Sayers created Peter while she was a struggling ad writer. (She is believed to have originated the phrases “it pays to advertise” and “Guinness is good for you.”) Furnishing his glorious Piccadilly flat while she herself was penniless (without even the benefit of Patreon or Ko-fi) was greatly satisfying to her. She said it was the cheapest way of feeling rich that she could think of. It’s not difficult to understand the impulse.