Even a nonbeliever might find it useful to model himself after God. (Cormac McCarthy)

The Book of J is largely agreed on by Biblical scholars to be the oldest writing in the Bible, more precisely in the Torah: a strain that passes through much of Genesis and Exodus, some of Numbers, and a fragment of Deuteronomy. (Nothing at all of Leviticus, which matters.) Although effaced by centuries of editing and translations, it’s still there: as an exercise, read the first two chapters of Genesis and spot the break where the text changes from the later P (Priestly) story to J’s version. Once you know to look for it, it’s so clear, the outline of a buried city among the ruins. (The J author is known as the Yahwist, because one of her characteristics is to always refer to God as Yahweh. Since the scholars who first named her were German, she is given the initial J for Jahwist. If Americans had done this as we are goddamn entitled to, we’d be reading The Book of Y here.)

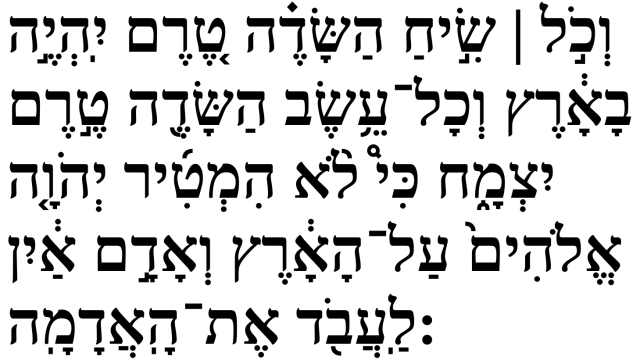

The Book of J consists of J’s text, given a new and close translation from the Hebrew by David Rosenberg, who said he wished to recover the “original weirdness” of J’s voice, and a thorough commentary by Harold Bloom that gives both a history of writing, translating, and critiquing the Bible, and a thorough exegesis of the text itself. (Bloom, A GREAT BIG FAT FUCK in the words of one of our most J-like contemporaries, spent so much of his career as an old man yelling at literary clouds but does his very best work here.) Bloom explores the role of J in Western culture, in Judaism, in Christianity, in scholarship, but mostly he operates, simply and directly as nowhere else in his writings, as a reader, awakening us to plot, character, and tropes, bringing us back to an author almost three thousand years old, if she ever existed.

Where no one has yet equalled J is in depicting the psychology of God. (Bloom)

Two reading strategies:

- Read in it order: Bloom’s “the Author J,” the Book of J, “Commentary,” “After Commentary.” “The Author J” does a good job of introducing Biblical scholarship, J herself, and the history of Biblical translation–especially the last chapter, “Translating J,” where Bloom looks at different versions of the Babel story. It makes for a fine overture to the Book itself. The “Commentary” section can be skimmed or skipped entirely–it can get too pedantic, too single minded, too cranky–but “After Commentary” should be read, and closely, because here Bloom broadens the reading of J, exploring his own view and that of much Biblical scholarship.

- Dive straight in, read the Book of J on its own, and check out the rest of the commentaries at your leisure, or don’t. More than anything, what made this work take hold in my life, just as The Shield did, is its strength as a story, and commentary can only deepen that, not create it.

Either way, be sure to check out the two short Translator’s Appendices at the end. In one, you get the passages of the Bible indexed to the J text; in the other, Rosenberg discusses the details of his translating: word choices, rhythm, reference, “the stance of the poet” in his words, and every sentence illuminates something. His revelation of his model for J’s prose has the force of a last-second twist that makes sense of everything that comes before, and I won’t spoil it here.

See you back here March 1st February 28th for the discussion. L’chaim!