First of all, a content warning: if you have an aversion to the word cunt you need to stop now and not read this book. I mean, we’re all adults here, but fair warning.

Secondly, isn’t Will Self the best author name ever? Will. Self. It’s not even a pseudonym. Just a fantastic name.

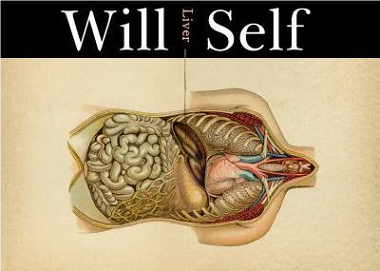

Okay, now that’s out of the way, here’s a brief introduction to Self for those that are unfamiliar. He came up in that wave of mid-1990s British cultural excitement, ostensibly as a subversive shock artist. He was promoted as an enfant derelicte. But really he is a writer who cannot be otherwise and would be a writer in any other age. (That doesn’t mean he didn’t faff around London with Damon Albarn and Damien Hirst doing a bunch of coke.) His mode from the start was grotesquerie and you’ll see a fair amount of that in Liver. This is combined with a recursive streak where characters and places tend to reappear in his books in various guises, never with explanation, which creates a kinda dream state to his books as a whole. He has since moved into modernist writing, the kind with no paragraph or chapter breaks. I don’t really enjoy that but it seems like a natural evolution. Liver is one of the transitional books between his early and later modes, and it’s fairly accessible.

So, why did I want to share this book? Well, it’s conversational. I doubt you’ll be ambivalent about it. I really enjoy it as a thing, especially since the hardcover is basically a work of art. Also, it’s an easy introduction to his work. There are four short stories around a theme, with variant styles, and you’ll experience Self’s obsessive love for vernacular language and archaic verbiage.

To introduce, I’ll give you the book’s outline from the inner-cover, because pre-warned is fore-warned or something (I can’t remember the phrase), and also it’s a neat bit of writing in and of itself:

1) In Soho, at the private members’ Plantation Club, it’s always a Tuesday afternoon in mid-winter, and the shivering denizens of this dusty realm spend their days observing its proprietor, Val Carmichael, as he force-feeds the barman vodka-spiked beer, re-enacting the gavage perpetrated upon geese by poultry farmers in the Dordogne.

2) For Joyce Beddoes, whose useless daughter can often be found within the Plantation’s nicotine-stained walls, things aren’t much better. A retired hospital administrator, she saw enough of death professionally not to succumb to its creeping normalcy. Instead, diagnosed with terminal liver cancer she’s on her way to be euthanized in Zurich. Here, in the cockpit of Swiss orderliness, a messy death can, she hopes, be avoided.

3) Prometheus, a young copywriter at London’s most cutting-edge ad agency, is prey to a different kind of mess. But although a griffon vulture feeds on his liver thrice daily, he’s always in the pink the following morning and ready for that all-to-play-for pitch.

4) If blood and bile flow through liverish London, the two arteries meet in Tony Riley’s subterranean Kensington flat, where ‘career junky’ Billy Chobham performs little services for the customers who gather to wait for the Man. When Cal Devenish, the young writer of the moment, drops by after an afternoon in the Plantation, he makes a friend for life. Just like the liver itself, in Liver what goes around comes around.

Joins us for a discussion on Liver at the end of August!