I am pretty sure that I first encountered Italo Calvino’s If On A Winter’s Night A Traveler… in one of the most obnoxious ways a college student could encounter anything: I bought it at a college bookstore for a class I was not taking. One of my favorite habits as an engineering college student was to hit up the booklists of other classes and buy copies of their non-textbook books that struck my fancy. I picked up a variety of texts in this fashion, from Douglas Hofstadter’s Godel Escher Bach (I keep getting stuck at the logic puzzles) to Jon Lewis’ Hollywood vs Hardcore to Nabokov’s Lolita and probably even Vonnegut’s The Sirens of Titan. So much of my college literary education was formed by teachers whom I never had and classes that I never took.

When I was a sophomore, Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves was burning through my university. I first read a review of the horror novel in a now-defunct electronica magazine…yes, you read that right, when I was a student librarian, we got in DJ magazines, and one had a two-page glossy spread dedicated to a horror novel. If I remember right, the magazine was also released months after the novel was released, making it even stranger. My friend then recommended House of Leaves after she and her TA bonded over not reading the class assignments but devouring this book for weeks on end. I read it during the summer, and you could still spot students with this doorstopper of a novel. House of Leaves is a gateway novel – some might derisively call it Baby’s first postmodern novel – in which metafiction and reference are used to play literary games with the reader and disorient them from reality. In turn, I would pick up Calvino’s novel which was an oft-cited reference to House of Leaves as an example of split narratives, endlessly branching possibilities and metafiction where the narratives within the book influenced each other.

I didn’t know Italo Calvino’s If On A Winter’s Night A Traveler… shared many of the same roots as October’s The Red Tree, including Borges’ Ficciones which would also be cited as an influence to House of Leaves (which, in turn, was also cited by Kiernan as in influence in her postscript). Nevertheless, it pleases me that we started with The Red Tree and are moving backwards to Calvino as the deconstructionist roots of Borges flows deep and wide. In his essay Kafka and his Precursors, Borges wrote “In the critics’ vocabulary, the word “precursor” is indispensable, but it should be cleansed of all connotation of polemics or rivalry. The fact is that every writer creates his own precursors. His work modifies our conception of the past as it will modify the future.” Similarly, as a reader, my reading House of Leaves influenced my reading of If on a Winter’s Night A Traveler, Ficciones, Infinite Jest and The Red Tree. In turn, my subsequent reading of all those novels will influence this re-reading of If On A Winter’s Night A Traveler. There is a game of reference and influence that happens both within these novels and without, in turn influencing the deconstruction of time and narrative into a rabbit hole of trainspotting. As such, my experience since first reading Calvino’s novel has changed me, and will in turn change my reading of the novel.

Enough about my history with postmodernism, what about the book?

1979.

Italy.

The world into which Italo Calvino released If On A Winter’s Night A Traveler… was a world fraught with political global tension as constant economic crises marred all countries. Calvino was born in Cuba to upper class parents with Italian government jobs and moved back to Italy in 1925. At the time, Italy was under the rule of Mussolini’s fascist party, but his parents were anti-fascists with beliefs in freemasonry, anarchism and Marxism. In turn, Calvino became an Italian draft dodger during WWII, and would later align himself with the Communist party until 1957 when the Soviets invaded Hungary. In the 1960s, Calvino became infatuated with Che Guevara and even wrote a tribute to him. In 1967, he briefly moved to Paris to experience the civil uprisings that were happening at that time. And, by the time 1979 rolled around, Italy was still struggling with their own place on the world stage.

To fully appreciate Italo Calvino’s If On A Winter’s Night A Traveler…, I recommend becoming comfortable with the idea that there are no real endings, but endings are everywhere. The story herein is told in the second person where You are a reader trying to read the new copy of Italo Calvino’s If On A Winter’s Traveler…, and are thwarted by numerous circumstances. Each circumstance brings a new development to the world. The story is a narrative of learning and development, influenced by what You’ve experienced and being controlled by the outside influences that control your life. But, it’s also a novel that plays games with the reader.

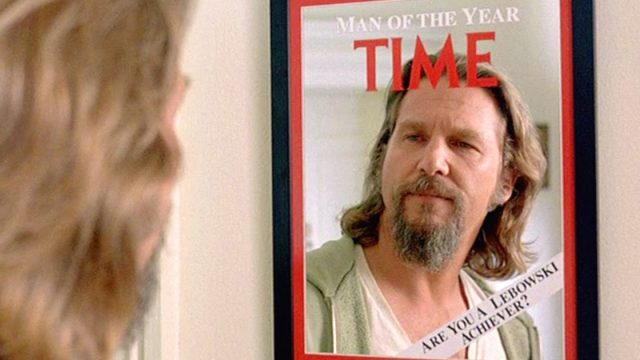

All of the politics and games within the novel give the reader a dizzying sense of grandeur. Some of the games are obvious – the novel you’re trying to read influences the way your life is perceived and the decisions you make – but others are less so (read the opening phrases of the books). That said, I don’t want to provide a roadmap for this book. This intro is to merely give you some grounding for where I’m coming from and where I think the writer is coming from. In fact, I recommend that you should feel free to ignore and forget about this whole essay as it should not influence how You read the novel. Even if you knew nothing about the world in which the novel was born, the politics of Italo Calvino, or my own approach at the novel, hopefully you will find this novel a zippy, zesty and delightfully batty read. At its heart is a neo-noir starring You, and if there’s one thing I know about this website, its that we appreciate a good neo-noir. Above all else, remember to have fun with it.