When the AV Club announced in early 2013 that they would be reviewing early episodes of The Shield, I intended to write a few posts about how good it was. It’s something I had been pitching on the Sopranos boards (especially in my post on the finale), that The Shield wasn’t just a great show, it was a show that was great in a very different, and very classical way. I wrote the first three pieces that went up for the first two reviews; I’d gone over 3000 words and still felt like I was just getting started. This project started to develop its own momentum as I rewatched the episodes, found the careful details of plot and character that would pay off later (“admit you’re evil” at the end of “Carnivores” just fucking floored me), saw what worked and what didn’t work and how the creators adjusted for that, and got caught up in the sheer pleasure of following a great, archetypal story.

The best part of all of it, without question, was interacting with the community of the AV Club, and then here. I had first the inspiration of the TV Club’s great writers–Donna Bowman, Noel Murray, Steven Hyden (who reviewed The Shield’s final season when it aired), Zack Handlen, and Todd van der Werff, whose criticism of The Shield remains the most revealing thing I’ve ever read on why it was never a full critical success. More importantly, I found readers who loved The Shield as much as I did and wanted to articulate that, challenge me further, and inspire me to keep going. Whatever worth these essays have, they have so much more worth because of what everyone else said. (Shit, even Brandon Nowalk said one or two interesting things.) I approached writing these essays every week knowing that an audience was going to pay close attention, and I had damn well better live up to that.

In no particular order, and with huge apologies to anyone I leave out, thank you so much to Perfect Circles, AlonsoWDC, MRobespierre2, pwhales, pw exclamation mark (same person?), SG Standard, BalloonsBalloonsBalloons, Anarchist Cat Owner, Janine Restrepo, TeacherinChina, Cali/AgThunderbird, geoffzilla, snake doctor, TheRawBeatsdotcom, thesplitsaber, rct, Stingo the Bandana Origami Pro, BalthazarBee, Affrosponge88, medrawt, loopcloses, Rafa, K. Thrace, The Canadian Shield, and zedhed. (Seriously, if you’re not on the list, let me know so I can edit you in.) I suspect, that more than other communities of fans, if you mapped out all of our favorite works, they would intersect only on The Shield. Storytelling is probably the most ancient of art forms, and its ability to move us and unite us goes so much deeper than aesthetics.

Particular and bonus thanks go out to Wad (VanDerTurf) for his thorough and weekly insights, and his effort in compiling the guide to all these essays, to ZoeZ for her insight and for writing the truest goddamn thing anyone ever said about this show, and of course to ZODIAC MOTHERFUCKER, our finest poet of ownage, for doing so much to promote this work and for being the goal I had to meet. It is the humblest thanks I can give (and I am not often humbled, ask around) that I will sign these essays here in my true name.

“Is that what you really want to see happen?”

The Shield states its deepest truths in the simplest, most everyday language. The power of that line (Billings’ lawyer says it) isn’t in its poetry or its originality; the power comes from the way all 88 episodes have relentlessly demonstrated it. The deepest, most necessary element of storytelling is consequence, and that’s something more fundamental than right-and-wrong, or judgment. (A lot of shows in our Second Golden Age of Television have been praised for their strong sense of right and wrong, and I don’t get that. It’s not that these aren’t great shows; I just fail to see how it takes great moral courage to say that a mob boss or a meth dealer is a bad person.) Judgment asks us in the audience to evaluate, and you can do that for free. Story, though, asks “what will happen?” and if we can accept that.

The Shield structures its incidents to continually confront its characters, and therefore us, with that question, and it raises that question to its most impossible level. Can you accept Kavanaugh as the price for getting rid of Vic? (Can he even do that?) What compromises will you make to clean up the Barn? Will you kill a friend to protect your family? How far would you go to preserve your sense of who you are? Would you kill your family rather than let them be split apart? The Shield doesn’t just raise these questions, it shows us how people answer them and makes us feel those answers. It’s not a work about mystery, it’s about clarity, about taking these decisions and making them absolute and unavoidable.

That’s why Aristotle insisted that plotting–“the structure of the incidents”–was the most fundamental aspect of tragedy. Tragedy isn’t about describing characters, or showing how they fit into society, or describing a particular place and time, or exploring them psychologically, it’s about actions and consequences. The principles articulated over two millennia ago still work, and The Shield carried them out with a rigor never surpassed on television: there are initial actions, which cause consequences, which cause further actions, which continue until the ending, the last consequence of the first action. The Shield also follows Aristotle’s principle of the unity of action, and that pays off here at the end. Tragedy is most effective when it follows the consequences of a single action; really, The Shield has only two initial actions: Vic killing Terry and the Team robbing the Money Train. Everything follows from them. Part of what makes this ending so powerful is the way it necessarily comes back to that first action. That’s what makes it a true ending–there is nothing more that can be said or done.

A story like this isn’t a personal work. The Shield commits to things that are not personal: the genre of the police drama; the law of probability within that drama; and a style that resulted from a collective effort and trial and error. The nineteenth-century Romantic attitude that a work reflects an author’s history, psyche, emotions still dominates our contemporary criticism, though, and a lot of criticism works to figure out the author’s intention or meaning. The Shield doesn’t work on that level, and neither do our great dramatic works. It’s not the psychology or the purpose of Shakespeare or Euripides that moves us hundreds or thousands of years after they’re dead, but the emotions and actions that endure.

The Shield follows the rules of theater, not novels or cinema, the two forms (and forms of criticism) that dominate the Second Golden Age of Television. More than any other great contemporary show, it gets its power from what it leaves out. It doesn’t have anything like the florid surfaces of Hannibal or the cinematic wonder of Breaking Bad; not the journalistic complexity of The Wire or the psychology and history of Deadwood or The Sopranos. All of those things, though, speak to the particular, they speak to our time, so it’s no surprise that they get praised by the critics of our time. The Shield aims at the universal emotions and experiences, and by definition those will last longer than the particulars of state and federal immunity deals. Drama removes everything except what’s necessary for its story, and because of that, drama can travel through ages, places, and settings, and it can bring insight across those times. (William Gass reminds us that we only interpret weak literature. Great literature interprets us.) Once upon a time, a man did a bad thing and thought he was still a good person; he got away with it, and lost everything else. That’s The Shield, and that story will endure and be told as long as there are people, consequences, and ethics.

Most fiction of our time doesn’t take this approach to plot or character; probably the biggest influence on our contemporary conception of character is Freud, for better or for worse. In Harold Bloom’s word, Freudian characters are always overdetermined; they are made by their past, by their childhood, by their traumas, and that determines their actions. That’s why, I suspect, that so many contemporary dramas rely on backstory. They are not seeking to show the consequences of action, they are trying to explain why people take the actions they do. That’s fascinating, but that’s not drama.

Drama is about choice, and living with that choice, and The Shield never lets us forget that. We see the choices that started it all, the choice to kill Terry and the choice to rob the Money Train. (We see the process of choosing the second one, too, which is why the second season is so essential, and so good.) One after the other, we see the consequences until there are no consequences left; it’s why the narrative of The Shield always moves forward; no explanations, no justifications, only consequences. (It’s why the worst episode was the one that went into the past to try and explain things.) Drama understands people as fundamentally capable of choosing, acting, and living with the consequences; that is why, for all the horror of these final episodes, The Shield ennobles us rather than depresses us. It doesn’t make us comfortable, or tell us we’re good; it says we choose, and our choices make the world; it says that we matter and that we have to live in the world that we make. It tells us what Robert Penn Warren said in All the King’s Men: “It might have been all different, Jack. You got to believe that,” possibly the most fundamental element of storytelling.

The moral calculus of Vic Mackey, as demonstrated throughout the entire series, and most clearly now:

5. Uphold the law

4. Deliver ownage to evil (subclause: protect women)

3. Protect the Strike Team

2. Protect the family

1. Protect yourself

Vic’s tragedy spins out of two things. First, his hubris: he always thinks there’s a way to do all of #2-#5. Vic has always done everything he can to follow whichever principle he’s following, and he doesn’t think that conflicts with the higher principle, right up to the moment it does. Then he throws away that principle and whoever got protected by it, with Terry Crowley the first victim of this and Ronnie Gardocki the last. Second, his self-righteousness: he doesn’t see principle #1. Behind every single Mackey scheme and plot, he assumes that he will not have to sacrifice himself. He might risk himself, but his hubris always makes him think he won’t have to make that choice. (The exception to this was back in season two, when he was ready to give himself up for Armadillo. He was saved from doing that by Shane and Lem, who arguably sealed their own fates there.) You can compare this to the different calculus of Shane and Ronnie: Shane genuinely has #2 as his first principle, and Ronnie knows his first principle is #1. Now, in the last episodes, events force the characters to act on these, and nothing else.

Shane has gotten even more desperate in protecting his family. The escalation of these last episodes has followed a pattern: “twist things for your characters, and then twist them again, then twist them again, and back your characters into impossible situations and see how they can possibly try and get out.” (Noel Murray) Coming off the real estate robbery, Shane now tries to heist some of his old Vice contacts, which goes bad so quickly. They know he’s a cop, they load him with cocaine cut with speed (for the rest of the series, Goggins plays Shane with a desperate overcontrol, as if he could slip into drug-induced mania at any moment; when he screams “give me the money!” you can hear the control breaking), and we get brief shots of them looking at each other just before they attack. (Billy Gierhart was the camera operator for most of the series and “Possible Kill Screen” was his first directing credit. Shawn Ryan gave him a single note: “don’t fuck it up.” He didn’t.) It’s like the Shane/Tavon/Mara fight in its intensity, sense of damage, sense of a closed space that limits the action, and most of all in the way Mara comes in to save Shane–only this time she shoots a woman, in the back, dead and gets a fractured collarbone.

Shane’s options narrow down to pretty much nothing now; Mara’s committed a felony and that ends any chance for her to stay free and keep Jackson. You can see the difference between Shane’s morality and Vic’s all the way through these episodes, in that Shane isn’t trying to save himself at all, in fact he’s desperately offering himself as a sacrifice, telling Billings he’ll come in and trying to get his lawyer (Lewis Black in a voice-only guest appearance) to cut a deal. One of The Shield’s most iconic and harrowing moments has a nearly-destroyed Shane with a gun in Tina’s face crying “my wife is not going to jail!” You can feel in that moment, in his tears and in the break in his voice, Shane’s need for that, and its impossibility; you can also see how much Tina has grown as a cop. (Tina had problems with procedure at the beginning and occasionally downs the bottle of wine after hours, but she’s had a core of strength in place since “Jailbait.” The way she just looks right back at the gun in her face says everything about who she is now.) What makes Shane’s story even more harrowing in “Possible Kill Screen” is that he’s in a race and doesn’t even know it, as Vic and Ronnie move closer to an immunity deal with ICE. (That also makes sense for the episode title.)

We’ve seen, so many times, how The Shield can jumble its tones, and the fact that the remnants of the Team are at all-out war doesn’t exclude some of the funniest moments in the Vic/Aceveda alliance. Vic’s line about Aceveda’s “moist little speech” is great, but the transcendently funny moment is Aceveda telling Olivia how she got her education at Quantico, and Aceveda got it on the streets, man–Benito Martinez even puffs up his chest Chiklis-style to do it. It’s hilarious, and of course it’s also a key plot point, keeping Vic in play with ICE and encouraging Olivia to make the immunity deal with Vic.

We’ve seen, so many times, how The Shield can jumble its tones, and the fact that the remnants of the Team are at all-out war doesn’t exclude some of the funniest moments in the Vic/Aceveda alliance. Vic’s line about Aceveda’s “moist little speech” is great, but the transcendently funny moment is Aceveda telling Olivia how she got her education at Quantico, and Aceveda got it on the streets, man–Benito Martinez even puffs up his chest Chiklis-style to do it. It’s hilarious, and of course it’s also a key plot point, keeping Vic in play with ICE and encouraging Olivia to make the immunity deal with Vic.

The Shield’s treats Olivia as a real character and not just as a plot element. That is, she wants something, she has strengths and weaknesses, and she acts according to them. With Beltran in town and a delivery of drugs coming in, she’s got a narrow window of opportunity to make an arrest, and Vic plays on that; it’s why he can turn down the first offer of immunity because Ronnie isn’t included. Vic’s still at principle #3 here and still thinks there won’t be a need to escalate. However crazy the deal Vic makes appears, it’s no less plausible than the story of the informant “Curveball” in the run-up to the Second Iraq War. Informants can exert a lot of leverage with governments if they tell them what they want to hear, and Vic exerts additional leverage by forcing the deal to happen now.

There’s another escalation going on with yet another set of characters. Corrine’s coming close to breaking here, knowing that it won’t be long before Vic figures she’s turned. Dutch and Claudette keep their loyalty to Corrine here and try for another shot at picking up Vic. Corrine tells Vic that Mara’s panicked and is now demanding a car as part of the deal, which leads to the wonderfully funny moment of Vic with a child seat. Vic spots the surveillance, though (it would be implausible for him not to spot it, and implausible for there not to be any) and Corrine gets arrested so he can see it. In that moment, right before the commercial break, Vic looks as panicked as Shane, and for the same reason: there are no options left.

These precise escalations, one event after another, of “Possible Kill Screen” brings Vic to Olivia’s office, needing to make the immunity deal for himself and for Corrine, and right now. (Fantastic line reading by Laurie Holden: “might be construed?” Somehow she gets the way she raises her eyebrow into her voice.) Here’s where we see the dramatic unity of The Shield at its strongest. For the entire series, beginning with the unseen moment in the pilot when Gilroy told Vic that Terry was undercover, he’s been asked to admit he’s evil. Shane in “The Spread,” the Fruit of Islam in “Carnivores,” Danny, Lem, Becca, Ronnie, Shane, Aceveda, all of them and the events of three years have said to Vic “admit you’re evil,” and he never has. Now he has to; now the deal, explicitly, is right there: admit you’re evil and you get away with it, with all of it. Sacrifice the last remaining Team member (the way Vic says “Ronnie can wait until next week” lets us know that he knows exactly what he’s doing), destroy rule #3 and you save #2 and #1.

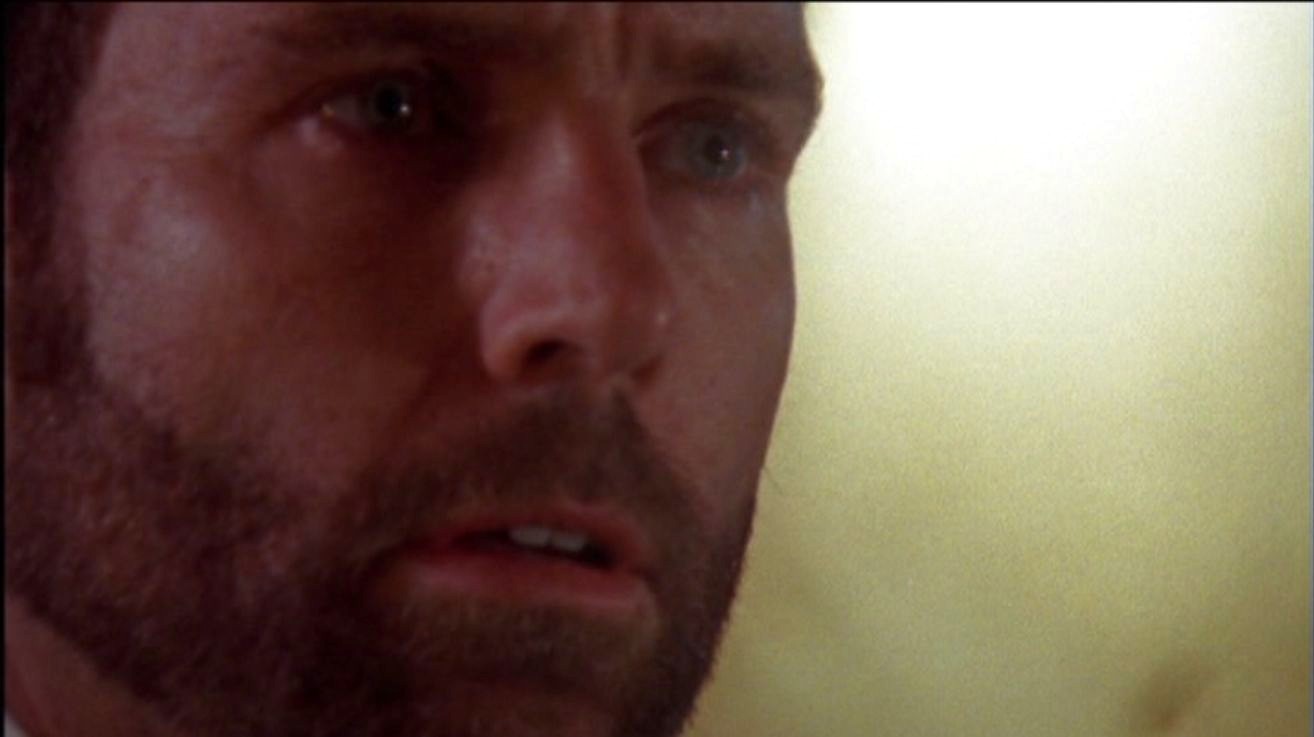

ICE’s confession room is The Shield’s barest stage ever, and the ambient sound gets dropped to its lowest point, just a barely audible air conditioner. That’s exactly right for this climactic moment, where it will be about nothing but the action. Chaffee moves to a listening post, and there will be only Vic to confess and Olivia to listen and record. “Anytime you’re ready,” she says, and Vic pauses.

That pause, forty-three seconds long, gives you enough time to hold your breath. It gives Vic enough time, like Michael Clayton at the end of Michael Clayton, to remember everything that got him to this place. It’s enough time, as many viewers have said, for Chiklis to age himself ten years. It’s enough time to say the words of Joseph Conrad, who, over a hundred years ago, perfectly described a moment of a bald guy coming to a less detailed but not less absolute self-knowledge. Art does things like that:

It was as though a veil had been rent. I saw on that ivory face the expression of sombre pride, of ruthless power, of craven terror–of an intense and hopeless despair. Did he live his life again in every detail of desire, temptation and surrender during that supreme moment of complete knowledge?

The camera keeps closing in on him, all his other options burned by the actions of three years. The pause ends, and right away, without any attempt to justify it or explain it or hesitate further, without any attempt to deny he’s evil, Vic closes the circle and brings himself back to his first action:

“During a raid on a drug dealer named Two-time, I. . .shot and killed Detective Terry Crowley.”

The moment that scares me the most is Vic’s slight turn of the head and the way he points: “I planned it. I carried it out. I shot him once. Just below the eye.” It’s mechanical, dissociated, the words delivered in staccato; Vic’s not really in his body right then; he can only state this moment by moving somehow outside himself. Chiklis is so fluid an actor here, he seems to make his skin transparent to Vic’s emotions. When he says “I was too good,” you can hear how the force of that line hits him; not as heroism or virtue, just the simple truth about how he always got away with it.

That was the hard part, and after that (broken by a commercial), he gets rolling, detailing every last thing he did, every last violation, death (watch him admit to Margos, he’s mournful but more present), theft, lie; he’ll say later that Shane’s document helped him remember a few things. All the time, Olivia just looks more and more devastated, bleak; Holden gives one of the great reactive performances here, and the scene doesn’t work without her. (In the listening post, Paul Dillon’s face has the same look of Phillips and the Chief listening to Kavanaugh’s rant in “Of Mice and Lem”: he’s thinking this will be a PR nightmare if it ever gets out.) Vic grows more confident, but he’s a different person; he doesn’t have the fronting of the last seven seasons. Confession, whether religious or psychological, is never about letting others know what you did; it’s about facing it yourself, and that’s what Vic does here. Here he truly burns off his self-righteousness and it liberates him. He sat down at the table proclaiming, and even believing, that he was a good cop who cut a few corners, took a few risks, and a good man who always protected his family. He stands up from the table as a thief, a killer, and a liar, and he knows all of it. Behold, now, the true Vic Mackey.

“Do you have any idea what you’ve done to me?” asks Olivia, and I don’t know a better line ever uttered by a tragic hero than what Vic says to close out “Possible Kill Screen.” There’s no attempt anymore to find the solution that saves everyone. There’s no attempt anymore to deny he’s evil. What’s there now is the man who knows himself, who has killed and stolen and lied and destroyed and betrayed, and knows that sinking someone’s career just doesn’t rank. He has become ownage. “Judge all you want, be hurt all you want,” he says, “if you met Vic Motherfucking Mackey and this is all I did to you, consider yourself one of God’s chosen.” All of this in three words: “I’ve done worse.”

“Do you have any idea what you’ve done to me?” asks Olivia, and I don’t know a better line ever uttered by a tragic hero than what Vic says to close out “Possible Kill Screen.” There’s no attempt anymore to find the solution that saves everyone. There’s no attempt anymore to deny he’s evil. What’s there now is the man who knows himself, who has killed and stolen and lied and destroyed and betrayed, and knows that sinking someone’s career just doesn’t rank. He has become ownage. “Judge all you want, be hurt all you want,” he says, “if you met Vic Motherfucking Mackey and this is all I did to you, consider yourself one of God’s chosen.” All of this in three words: “I’ve done worse.”

It’s made even more powerful by the confession just before it. If the fundamental story of The Shield has been Vic’s journey to admit he’s evil, a close second has been the battle of Vic and Mara for Shane’s soul. Mara won almost immediately, and held on, and not just because she could offer Shane love, sex, and a family. She won because she could forgive Shane, and Vic never could. As far back as “The Spread,” when Vic said “get over it, and don’t bring it up again,” Vic always moved forward and forgot the past. Shane never could, and it’s a scene that got repeated at the end of season three and split the Strike Team. If you can’t admit you’re evil, still less can you admit your accomplice’s. Mara could hear Shane’s confession, and accept it, and it’s at the end of “Possible Kill Screen” that we can see why: because Mara can admit she’s evil.

The Shield sets Mara up as the moral counterweight to Vic, with Shane as the fulcrum, but it’s never so shallow as to present Mara = good, Vic = bad. Mara has her flaws and they’re very much Shane’s, too: selfishness, arrogance, impulsiveness. What counts, though, is her conscience. It took Vic three years to admit to killing Terry. It took Shane weeks to admit killing Lem. It takes Mara one day to say “I’m a murderer,” and to feel the entire weight of that. She never tries to rationalize what happened, although Shane does; she knows what it means to take someone else’s life, that it can never be erased or altered from her soul. Vic confesses and burns off his righteousness. Mara confesses and in that moment truly becomes good; it’s why Shane will say that the thing he first saw in her was “innocence.” (Her face somehow manages to be hopeless and darkly radiant all at once.) That innocence makes her accept, even demand her fate: no more running, no more avoiding what’s to come. Her last line in “Possible Kill Screen” accepts that; it’s almost as succinct as Vic’s, and could have ended the episode just as easily: “just take me home. Please, take me home.”

Formally, Vic’s confession climaxes the series, finishing the story begun with Terry. So, formally, “Family Meeting” is all anticlimax. That confession is the last real action of the story; Vic kicked over the dominoes and all the rest fall, one after another for 73 minutes. First, it’s Shane and Mara; in the preceding episodes, you could hear in Vic’s voice this huge and restrained anger toward Shane, especially in their phone conversations. Now, though, there’s no need to restrain it anymore. Their last conversation is enormous and fatal. Vic drops the news: he has immunity and there are no more deals to be made, nothing Shane can do. (The Canadian Shield has it right–Shane’s one-word response “bullshit” is the bleakest thing I’ve ever heard anyone say. It’s like his voice knows what that means but his words don’t.) From there it turns into the most vicious verbal fight, both of them trying to hurt each other as much as they can, with whatever they can.

In tragedy, the worst thing isn’t death. Everyone dies. The worst thing for Vic is to lose his self-image as a good man, and that’s where Shane hits him, countering with the revelation that Corrine has been working with the cops. Shane chooses the exact right words–“the mother of your children has been playing you. She would rather see you go to prison than to hug one of your own kids again.” Not “Corrine,” not “your wife”; we’ve never seen that she means all that much to Vic. It’s her role as mother that matters, the loyalty he always believed she had for him, the loyalty that even in these last episodes he believed she had. Shane brings all that down, and then Vic slams right back (after giving a great little “hang on” gesture to Ronnie) with the worst thing for Shane: I’ll visit your kids “when you and Queen Bitch are serving your mandatory life sentences apart” and be a dad to them, “muss their hair” (so scary on that line–that’s the Vic we saw at the end of “Possible Kill Screen”) and steal your legacy. Everyone dies, but Vic will take the memory of Shane and Mara from their children, and that’s what sends Shane into absolute, despairing rage.

Since the end of “Possible Kill Screen,” there’s been a despair behind everything Shane does (the Goggins is so phenomenal in the shades of desperation and loss he gives to Shane), as if on some level, he knows how it’s going to end but he needs to stay strong and care for Mara. You can really hear it at the beginning of “Family Meeting,” when they name their new child Frances Abigail, or Franny Abby. Now, with Vic’s threat still in his ears, with a last call to his lawyer going nowhere (“there’s no deal”), Shane heads to a drugstore, does a line of coke, and buys some stuff. The most frightening thing about this scene is that Shane’s back to being Shane, flirting with a sixteen-year-old and checking out her ass, and then leaving all his money on the counter. And then he says hi to a neighbor on the way home. All of these things should prepare us for the moment when he comes home, and listens, for one last time, to the measured cadences of Mara reading Jackson a bedtime story, and to what will happen when Shane calls “family meeting.”

There isn’t any way to prepare for what comes next, as the Barn breaks into Shane’s home, as Shane stops writing long enough to blow his brains into the wall like Guardo’s and send his head into the frame-in-the-frame of the bathroom doorway. It can’t prepare us for the sight of Jackson and Mara, dead, poisoned, on the bed with a truck and a lily, Mara looking like a carved figure on a medieval tomb. It can’t prepare us for the knowledge that Shane killed his wife and child to avoid having them broken up by jail and foster care. (ZoeZ found an interview with the Goggins where he interpreted Shane as telling Mara about the poison when he got home, and she went along with it; the letter he wrote was meant to clear Mara. Whether or not it’s true–since this is, y’know, fiction, we’ll never know–it’s completely believable that Mara would go along with it.) It can’t prepare us for the still, silent, empty moment of Dutch, Claudette, and Danny surround the bed with Mara and Jackson, and the cut to black.

Shane (and possibly Mara) killed a two-year-old child, and I just can’t imagine any greater horror. Yet the power of tragedy is such that we know exactly why he did it, we recoiled from Vic’s speech of “I’ll send you a postcard from Space Mountain,” we’ve felt the options and chances narrowing over the last six episodes, really ever since “Extraction.” That is the pity and terror we felt when Shane killed Lem, a thousand times worse here because it’s a murder of a true innocent. The power of drama isn’t to show us horrible things, it’s to make us feel what it’s like to do horrible things. That’s why so much moralistic criticism will miss the point of The Shield, because tragedy will make us feel for people that we would otherwise only judge. There are few moments in drama that push our empathy as far as this one.

Shane’s family dies with him; they actually do “make it together, or all go down together.” Vic goes to Olivia and discovers the consequences of his ownage: Corrine and the kids have gone into witness protection. (Claudette set it up with Olivia; as she said, “you want to hurt him and this is a way to do that.”) The brief scene where he finds out shows Vic jumping through all his characteristics, from puffing himself up at first (“Good. When can I see them?”) to the genuine shock, born of whatever self-righteousness he has left, that, wait, Corrine was working against good ol’ Vic Mackey? to the open display of self-pity (“I didn’t get to say goodbye to my children”). Olivia will have none of that, not after what he’s confessed, and hits him with another moment of recognition, one of the most powerful yet: “you said goodbye to them the moment you shot another cop in the face.” No one in all The Shield better articulated Vic’s morality, and the way it was always really about himself. Vic’s final look, as Olivia tells him “be here 9am sharp tomorrow,” throws forward to his final look in the Barn’s interrogation room at Claudette–it’s rage, because she’s right, and there’s nothing he can do or say.

Vic’s not the only one who faces recognition here. In the same way that Kavanaugh’s final arc served as a miniature version of the full-scale tragedy of The Shield, Dutch comes to his own moment of recognition in two stories that began earlier this season. In the first, Dutch has made Rita into Lloyd’s enemy, and Lloyd kills her, and makes an attempt to frame Dutch for it. It’s an easier recognition than Vic has to face, because Dutch was right about Lloyd; he still recognizes that it was his own actions that drove Lloyd to kill his mother. (There’s also a very funny moment when Claudette says “and he made you a suspect.” Karnes gives a perfect “what?. . .Oh.” reaction.) Kyle Gallner kills it, again, as Lloyd, playing hurt and tearful but somehow doing it one level less than fully convincing. This is only Lloyd’s second kill, after all, and it makes sense that he hasn’t mastered every aspect of murder just yet. He gives himself away when talking to Claudette: he says of Dutch “he burned her clothes” when Claudette hadn’t given that detail. (I did not catch this until it was pointed out to me.) Claudette’s little speech to Lloyd is a favorite moment here; she’s fully in command and it’s very much a classical moment of the detective nailing a suspect–Poirot or Maigret would have done something similar. I also love her line “I’ve even interviewed a few innocent people.” It’s not so much hopeful as a recognition that humanity comes in all flavors.

Dutch’s other recognition comes with the arrival of Ellen Carmichael, Billings’ lawyer. Dutch revealed to Claudette that Billings had Heap (the sex offender on his family’s block) framed, and Claudette called him out on that. The city has threatened to countersue Billings (no surprise there) and Billings wants Dutch to write a letter praising his “exemplary” detective skills and how they fell apart after the bump on the head back in “Baptism by Fire.” “He asked for a favor, I obliged him with the truth”–Heap gets released but Dutch writes an honest evaluation of Billings. Carmichael confronts him on that, telling him what could happen to Billings if the other side sees the letter. Again, this is drama, on the most microscopic scale: not the question of “is it right?” but, as she says, “can you accept what will happen?” The Barn is always a morally compromised world, for everyone, and it always has been; my experience has been that most of the world is like that. Dutch makes the choice, much like the choice he and Claudette made with Corrine: it’s not worth burning your relationship. He decides to rewrite the letter. Oh, and he may get a date with her if he remembers the card she gave him; he was just too caught up in everything going on to try and impress her (gotta love that his first line to her was “the bitch dyke?”) and wound up impressing her anyway.

This subplot also gives me the opportunity to mention the funniest damn thing I’ve ever heard in a DVD commentary, which happens when Carmichael shows up:

Shawn Ryan: Hey, it’s Julia Campbell Karnes, Jay Karnes’ wife!

Michael Chiklis: Now I know what you’re thinking folks–how did that happen? (general laughter)

Jay Karnes: Well Dave Snell has the great line here. He says “it’s stupid to cast Julia. It’s ridiculous enough that Jay got her, that Dutch could get her is just absurd (way more general laughter)

Another short and thematically important subplot gets resolved here. Since the end of “Petty Cash,” Claudette has gotten more and more bad-tempered towards Dutch, and that explodes at the end of “Possible Kill Screen,” as she just rips into him over the whole Heap situation. It’s clearly not about Dutch; a lot of commenters have noted that her speech was most likely intended for Vic. CCH Pounder just magnificently plays Claudette’s near-breakdown there, arriving just in time (as happens so often in tragedy) to see the devastation but not in time to prevent it, seeing Vic confess and get away with so much more than she or Dutch or anyone ever thought he did. She yells “you’re fired, you sanctimonious son of a bitch!” and, then, immediately after “ya heard!” looks like she’s going to burst into tears. That’s all it took–she just had to blow up at someone to get rid of all the tension and horror of what was going on–and Dutch completely gets what’s going on. The next morning, in “Family Meeting,” she and Dutch are back to where they were, and the whole story gets resolved with a perfect little exchange–“didn’t I fire you?” “It didn’t take.”

That matters later on, when Claudette says that Lloyd will break, given time–“if we can just outlast him, we’ll get to the truth”–she’s expressing the strongest form of what could be called The Shield’s counter-morality, the morality of herself, Dutch, Danny, Julien, even Billings on a good day. We hold on to our relationships. We act honestly. More than anything, we try to keep doing those things. We keep doing these things because that’s all we’ve got; as Claudette said back in “Baptism by Fire,” it’s the only way to fix this place. Nothing else will work; try for karmic justice, try to be an action hero and you bring disaster on at least everyone around you. We hold on to what we know to be good, because it’s all we have to battle the world’s relentless evil.

It’s an attitude and a morality as ancient as drama, exactly right for The Shield, and it’s not a depressing attitude at all. The Stoics held that you had to confront your place in the world and what you could actually do in that world, and what you could do was something limited, and that if you could honestly accept that, it would liberate you. The Shield isn’t a product of the Enlightenment, with its sense that the world can be made rational and ordered and good; it doesn’t see the world as fixable. (David Simon thinks the world can be fixed, we just aren’t doing it.) You can’t fix the world and you can’t fix your flaws, but you can know them and live with them and do the good you can by never, never giving up; Marcus Aurelius counsels “take away the statement ‘I have been harmed’ and you take away the harm.” Do that, and know this glory: no one can do better than you.

You can hear exactly that in yet another heartrending moment, right after that, as Claudette says the drugs aren’t working and there are no new ones, and that “this is the disease that’s going to kill me. . .sooner rather than later.” She tells this to Dutch, no one else, because that relationship is real, and she’ll keep coming in and doing the job until she can’t do it anymore. That’s heroism in this world, and ours; and when she tells Dutch “you just keep doing what friends do, it means a lot,” that’s love in this world, and ours. There’s something in her voice and performance that believably says she hasn’t fully accepted this yet, but she will; and her breathing makes you feel the exhaustion already there. Dutch’s open smile when she straightens his tie is one more of Karnes’ utterly emotionally naked moments; it makes me wonder how long it will take for him to start bawling at her funeral. (Place your bets. Over/under is 60 seconds.)

Against all of this, the last scenes with Beltran have a feeling not of triumph but of loss; Vic’s betrayal of Ronnie hangs over all of them. Beltran was never the Big Bad of the season, or the show, because in the end this was about the Strike Team’s fight with itself, and he was part of the means of that. The final scenes of this case are a strange mixture of exciting and elegiac: one more target, one more impossible situation where the Team is outnumbered (“that’s some real cowboy shit.” “Yee-ha,” says Ronnie), one more well-structured action sequence that depends on who is where, and what they can see, one more bust that gets Beltran and a huge load of heroin, and secures Vic’s position with ICE. That last thing is what matters about the whole sequence. It pays off with Ronnie’s grin and happiness with Vic, with us knowing what’s about to happen. The untriumphant, almost everyday, feel of the whole scene throws forward to what Claudette will say to Vic in the interrogation room.

Against all of this, the last scenes with Beltran have a feeling not of triumph but of loss; Vic’s betrayal of Ronnie hangs over all of them. Beltran was never the Big Bad of the season, or the show, because in the end this was about the Strike Team’s fight with itself, and he was part of the means of that. The final scenes of this case are a strange mixture of exciting and elegiac: one more target, one more impossible situation where the Team is outnumbered (“that’s some real cowboy shit.” “Yee-ha,” says Ronnie), one more well-structured action sequence that depends on who is where, and what they can see, one more bust that gets Beltran and a huge load of heroin, and secures Vic’s position with ICE. That last thing is what matters about the whole sequence. It pays off with Ronnie’s grin and happiness with Vic, with us knowing what’s about to happen. The untriumphant, almost everyday, feel of the whole scene throws forward to what Claudette will say to Vic in the interrogation room.

A question was asked in an earlier discussion: when Vic comes into the Barn, he gets a magnificently vicious look from the guy who buzzes him in, and everyone falls silent when they see him. (Great shoulders-back-head-held-high-you-can-all-go-fuck-yourselves walk from Chiklis here.) Does that mean his confession is all over the Barn? And if it is, why hasn’t Ronnie taken off? There’s an answer to that right here. After the Beltran bust, Olivia tells Ronnie that Claudette needed him back at the Barn, and a uni would take him. From that moment on, Claudette effectively has custody of Ronnie, so even if he found out he couldn’t go anywhere. My read is that Claudette let people know the news of Vic’s confession and immunity deal, but not that Ronnie had been left out of it, and that she led Ronnie into the Strike Team clubhouse and hit him with the news of Shane’s death. He wouldn’t want to walk out then, not until he’d talked to Vic; even if he did, he’d never get out of the Barn. Claudette’s plan was most likely exactly what happened–confront Vic and then arrest Ronnie in front of him–but she wasn’t taking any chances.

Among the cameras filming the aftermath of the bust, Aceveda gets a definitive, funny, and cruel moment as he smiles and says “I have been leading it undercover for several months” about the Beltran case as Vic walks by. After seven seasons, I can only smile at him; as James Ellroy sez, “I find it hard to hate people who are that true to themselves.” As Claudette sez, his election as mayor is pretty much a lock now. The cruelty comes from the way Aceveda’s last triumph gets played against another story, and our final visit from a past guest star: the killing of Bobby Huggins, played by the walking charisma bomb André Benjamin. Huggins, campaigning for mayor on the New Paradigm ticket (“vote for me and I’ll set you free”–Benjamin finds so many ways to read that line), is one more in a long line of Shield idealists who just won’t make it in this world. Huggins speaks the truth about the prison-industrial complex, he knows how to work a crowd (Benito Martinez sez that when Benjamin gets the crowd on his side, it’s not acting on their part–he actually does get the crowd on his side and Martinez had to try and get them back), he can charm the guys in the Barn’s jail cell, and he winds up shot trying to shut down a crack house, with Tina to witness his death in an ambulance. It’s a funny and sad story, reminding us that in the world of The Shield, Farmington will not change. There won’t be a new paradigm, only the stories of the corrupt and the less corrupt.

The scene in the interrogation room has few equals in all drama; we watch someone damned here. The only thing close to it is Will Munney on the hill in Eastwood’s Unforgiven: the precise reading of one’s crimes. Claudette directs Vic to sit in the perp’s chair and his “excuse me?” is all he’ll say here, as she reads Shane’s last testament. Chiklis makes it look like Vic runs an endless loop of “fuckyoufuckyoufuckyoufuckyou” in his head, but that’s not preventing some of the feelings from getting past. When Claudette says “All those busts. All those confessions you got in here, illegal or otherwise. All those drugs you got off the street tonight for ICE. You must be very proud of yourself. This is what the hero left on his way out the door,” it’s the most complete and honest summary of who Vic is and what he did, the good and the horrific; it’s how The Shield doesn’t judge, but truly shows the consequences, all of them. Laying down the pictures, we get what Shawn Ryan calls the definitive Shield shot: Claudette going in and out of focus, temporarily blocked, CCH Pounder’s face utterly impassive and merciless. It’s what you would see and how you would see it if you were Vic, it depends entirely on the acting to make it work, and that’s The Shield. Vic’s internal monologue shifts to “fuckyoufuckyoudon’tmakemelookdon’tmakemelookFUCKYOUFUCKYOUFUCKYOU” and only after she leaves does he look, his head falling down.

The next few shots, as elegantly composed as the sequence of Two-man giving it up in “Parricide,” demonstrate one of The Shield’s forever themes: surveillance. We go from Vic looking at the pictures to a shot from his POV of the pictures, and then a shot of Claudette in the looking post, and then what she sees: Vic on the monitor. For the second time, the camera closes in on him, and this time there might be pain: his eyes are wet. (Michael Chiklis can twitch his facial muscles in character, that’s how good he is.) For the second time, he stands up, and like Kavanaugh in “Kavanaugh,” realizes he’s being watched. The look on his face is pure rage and hate, and it’s no wonder that Claudette flinches a moment. Vic ends the surveillance and kills one of The Shield’s longest-running characters, Interrogation Room Camera; he won’t take being looked at any longer. He tries to come up with one last clever line (“you can bill me for it”) and Claudette spins it right back on him (“fine. First payment’s due now”) and with one look at Dutch, sets the arrest of Ronnie in motion, with the shot from Vic’s POV of Dutch, Danny, and others heading to the Strike Team clubhouse.

If you want to know the difference between judgment and consequence, this scene shows it. Ronnie is as guilty as anyone for, as Dutch sez, “the last three years,” and deserves the same punishment as anyone else. Yet this sometimes feels like the worst betrayal, the worst hurt, because Ronnie should have gotten away with it. He was always the pragmatist, always the smartest one, always too careful to be caught, as Kavanaugh said. Shane and Vic made their fates from their flaws, but Ronnie simply made a mistake by trusting Vic for 24 more hours than he should have. This scene is a violation of causality, not morality, and that’s what lands on Ronnie’s face as he says “what?” and follows it with another one of the great lines in all tragedy: “you told them. . .all of it?” In the next moments, if Ronnie had been played by any of the other actors on The Shield it wouldn’t hit so hard. Chiklis, the Goggins, Kenneth Johnson, even Jay Karnes are all so physically expressive, but David Rees Snell has always been so reserved in the lines of his body that here he seems to transform into a cartoon ball of energy. With his dark hair and pale skin, thrashing and yelling (“you’re goddamn SORRY?”) in the middle of the arresting officers as they drag him into the cage, he becomes the Barn’s Tasmanian Devil. And beginning the last minutes of the series, there is nothing Vic can do but watch. The last shot of Dutch and Vic has a poetry to it, almost graceful as Ronnie rages. If I had to put words to what Dutch was thinking, it would be “I almost feel sorry for you. But you and I are done. Go.” Vic exits with Ronnie still thrashing in the background.

Going into his new job at ICE (suit and tie as required, for the first time since Terry’s funeral), Vic discovers he has nothing but a desk and a key card. There’s no one he can even threaten; the most telling moment comes when he yells “you can’t–“ at Olivia, and he doesn’t finish it, because there’s nothing there to threaten. She’s not even an enemy, just one more employee in a bureaucracy; even if he burns her somehow, there’s Chaffee above her and another agent will replace her. Vic has always been the guy who personally threatens people, makes personal deals, and now there’s no one to make a deal with. There’s no family any more, just three years of fifty single-spaced pages and a drug test every week.

Going into his new job at ICE (suit and tie as required, for the first time since Terry’s funeral), Vic discovers he has nothing but a desk and a key card. There’s no one he can even threaten; the most telling moment comes when he yells “you can’t–“ at Olivia, and he doesn’t finish it, because there’s nothing there to threaten. She’s not even an enemy, just one more employee in a bureaucracy; even if he burns her somehow, there’s Chaffee above her and another agent will replace her. Vic has always been the guy who personally threatens people, makes personal deals, and now there’s no one to make a deal with. There’s no family any more, just three years of fifty single-spaced pages and a drug test every week.

There are a few last scenes now for our characters, brief sendoffs before the whole thing concludes. Aceveda’s last scene, in Claudette’s office, uses an effective architectural device: the pillar in the office keeps the two of them separated in their own frames. Claudette and Aceveda can accept each other, but they’ll never be reconciled, visually or any other way. Corrine and the kids have ended up in Shawn Ryan’s hometown of Rockford, with director Clark Johnson (credited as “Handsome Marshal”) as their guide; Corrine’s smile suggest that just maybe, she’s found peace. Lloyd looks like he’s already given up; he’s like the guy who goes to sleep after a night in jail because he knows he’s caught. (He is an amateur, after all.) Dutch tells a last story about a serial killer, concluding with a line that defines the whole series and calls back to a season two episode: “the city’s roads are literally paved with dead bodies.” (Lloyd’s “everyone comes to Los Angeles to get famous” isn’t quite as defining, but it’s still good.) And during Tina’s first-year party, Claudette takes a moment to stand on the balcony and survey her domain. That location, more than any other in the Barn, has defined the captaincy; remember her and Aceveda conversing there in the pilot. The party continues, but there are shots fired and they’ve gotta go, with Danny coming back into frame to blow out the candle. Just another day.

There are a few last scenes now for our characters, brief sendoffs before the whole thing concludes. Aceveda’s last scene, in Claudette’s office, uses an effective architectural device: the pillar in the office keeps the two of them separated in their own frames. Claudette and Aceveda can accept each other, but they’ll never be reconciled, visually or any other way. Corrine and the kids have ended up in Shawn Ryan’s hometown of Rockford, with director Clark Johnson (credited as “Handsome Marshal”) as their guide; Corrine’s smile suggest that just maybe, she’s found peace. Lloyd looks like he’s already given up; he’s like the guy who goes to sleep after a night in jail because he knows he’s caught. (He is an amateur, after all.) Dutch tells a last story about a serial killer, concluding with a line that defines the whole series and calls back to a season two episode: “the city’s roads are literally paved with dead bodies.” (Lloyd’s “everyone comes to Los Angeles to get famous” isn’t quite as defining, but it’s still good.) And during Tina’s first-year party, Claudette takes a moment to stand on the balcony and survey her domain. That location, more than any other in the Barn, has defined the captaincy; remember her and Aceveda conversing there in the pilot. The party continues, but there are shots fired and they’ve gotta go, with Danny coming back into frame to blow out the candle. Just another day.

In the last scene, as the sirens of Vic’s lost life go by, he’s truly in the world that he made. Not deserved, but made, and that’s the morality of The Shield, expressed in consequence, not judgment. Aristotle counsels that tragedy must be about a single action, and Vic’s has been clear since the pilot: to get away with it and remain a good person. He did get away with it; as Wad pointed out, he even kept a job in law enforcement. All it cost him was everything in his life, his Team, his family, his shield, his identity, everyone who admired him. That happened not because Shawn Ryan wanted to make a point about the LAPD or America. It didn’t happen because he’s doomed by masculinity or capitalism or authority or anything else. It happened because of what Vic did, and that’s the essence of tragedy.

He sets out the last pictures, three of his children and one of himself and Lem. (Look familiar? That picture appeared in “Coefficient of Drag” with the entire Team in it, and again in “Parricide” and “Moving Day.” Now it’s framed so it’s just Vic and Lem.) “Who you got, Vic?” Shane asked, and this is all he has now. For the third time in these episodes, the camera starts moving in on Vic. The Shield has never been much for symbolism, but these moves are powerfully symbolic, and this one’s the most loaded. For the third time, the camera (assisted by a cut) closes in on Vic, removing everything active: the legs that chased, the cock that fucked, the chest that tackled, the arms that punched, moving all the way into the face, removing the mouth that lied and the mind that schemed. Finally there’s nothing left but the eyes, fearful in a way we’ve never seen before, only the receivers of information, that part of the body that can’t act, can’t initiate, that can only witness. Here, now, he witnesses his last fate, alone in an office with only the pictures of the only four people he didn’t betray or destroy. There is nothing left now, nothing more that can be done, all there is to do is witness; the consequences have all played out. The bullet he fired at Terry Crowley has finally come to rest.

Vic closes his eyes.

He opens them again. The lights go out and something changes in him. The Shield has always made its moves and its impact primarily with incident, and Shawn Ryan marks the end of a story in the simplest way: he starts a new story. Vic takes out his gun, and yes, there’s something going on there. He no longer has the shield that gave him authority or the jacket that he wore like armor, but he still has the gun; he can still intimidate, still commit violence, still destroy. For the third time, he stands up, and there’s intent in his eyes. He’s going to do something. And then others will react, and there will be consequences, and he will act on that, and that will be another story. But this one has ended and it’s time for us to go. The last line of the last script, Ryan’s farewell to Vic and our farewell to one of the greatest of all tragedies:

Vic Mackey heads into the night, destination unknown.

Grant Nebel, March 2013–December 2014