In 1994, young emulators of Bo Jackson or Tony Gwynn stepping to the plate (or extra glove or whatever was serving as home) to face a would-be Goose Gossage or Orel Herschiser would have their summer shortened by a tragedy. The major-league baseball season ended two months early due to the infamous 1994 players’ strike. The work stoppage truncated the season, begat the early retirements of several players and resulted in the cancellation of the World Series – a feat not even two World Wars had accomplished. Business had encroached on the supposed purity of America’s pastime before America had even thought of baseball that way. But the strike quickly and violently introduced a new generation to the idea that without money grown-ups couldn’t find a way to play a game kids gladly played (and in some cases worshiped) for free.

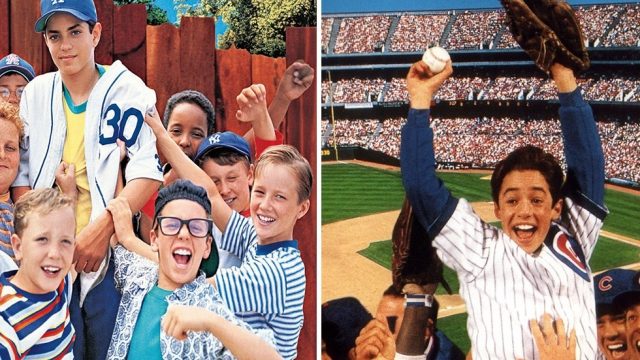

The year before, in 1993, baseball attendance set records that have yet to be touched in the twenty-four years since. There was nothing particularly prescient about The Sandlot and Rookie of the Year becoming strong box office performers during the 1993 baseball season. But you could hardly ask for two better films to create a stereoscopic image of the game’s appeal. One uses the trope of the Big Game, where our hero must pit ingenuity against power to win the division for his team. The other is an ensemble piece where the climax of the film centers around memorabilia and baseball history. For fans of a certain age, both evoke not just youth, but the last baseball season before the game let them down.

Rookie of the Year adheres a little closer to formula, hitting the beats with entertaining assurance like a Yankee lineup that puts on a show even as the outcome is never really in doubt. Henry Rowengartner (Thomas Ian Nicholas) is an enthusiastic boy who dreams of playing in the majors despite a lack of talent. He quickly wins us to his cause when he winds up in the laundry room, throwing a bundle of socks into the dryer and pretending it’s a major league strikeout. Fantasy becomes reality when a broken arm heals with the tendons too tight, giving him the ability to throw a major league-level fastball (the sound of his arm pulling back, like the rubber on a slighshot going taut, is an amusing recurring effect) When, in one of the film’s several great sight gags, he unexpectedly demonstrates this new ability at a sparsely-attended Cubs game, Henry scores a contract with his beloved Chicago Cubs. The team’s general manager sees him as the talent and – just as importantly – the novelty the team needs to attract enough fans to save the franchise.

There’s a light-hearted tone and enough genuine laughs that the film stays entertaining even as we hit the expected moments: Henry’s ascends into one of the hottest baseball stars, falls from grace as he grows apart from his friends, and faces a must-win situation where the magic disappears and he has to discover a way to win it all without his extraordinary arm. Do the Cubs win the pennant? Is the greedy general manager ousted and embarrassed? Does Henry’s frazzled single mother (Amy Morton) have a lesson to impart? Will she be rewarded with a grizzled Gary Busey? I wouldn’t dare spoil it.

Rookie of the Year dutifully recognizes that friends are more important than fame and tells us It’s Just a Game. But mostly it’s a celebration of the showbiz of baseball. The movie’s not concerned with the mechanics of the game in any realistic fashion. And while the economics of baseball aren’t particularly realistic either (the Cubs in Rookie have the exact opposite problem of the real Cubs at the time, whose fans would turn out no matter the quality of team, giving the ownership little incentive to spend money chasing titles), but the movie at least acknowledges the presence and impact of money in Major League Baseball. A plot point turns on a trade deal. Henry get fawned over by the models in a Diet Pepsi commercial (“You’ve got the right one baby!”). It’s the grandness of baseball without the grind of it.

The Sandlot, in contrast, is a Miracle Mets of a movie: a description of specific events that becomes folklore and a touchstone in a greater collective memory. Where Rookie is streamlined and modern, The Sandlot is episodic and nostalgic. It’s Stand by Me with PG-level swearing and fewer corpses.

Like the game it adores, the charms of The Sandlot are difficult to express through description alone. In the summer of 1962, Scotty Smalls (Tom Guiry) moves to a new neighborhood. He’s soon taken in by a group of boys led by Benny “The Jet” Rodriguez. The boys, who elevate rather than mimic “ragtag team” tropes, put up with Smalls’s ignorance of baseball simply because with him they can field a full team of nine.

The boys’ misadventures of the summer – one highlight involves some purloined chewing tobacco and a disastrous trip to the fair – keep returning to the sandlot and the friends’ daily dose of baseball. The movie’s ultimate antagonist is a large junkyard dog known as The Beast that stalks the other side of the sandlot’s fence. The myth surrounding the Beast, best related in the dark with a s’more in hand, involves the consuming of trespassers (bones and all) and is so strong that balls in his yard are given up as gone forever. That is, until a baseball autographed by Babe Ruth and unwittingly brought to the lot by Smalls goes over the fence. The movie drops all tangents and focuses on the fate of the ball and the attempts to retrieve it from the Beast.

In The Sandlot, professional baseball is on another plane of existence and populated by beings spoken of in awe. When Smalls reveals he’s never heard of Babe Ruth (“Who is she?”) the other boys become incredulous missionaries. “People say he was less than a god but more than a man,” explains Benny. “You know, like Hercules or something.” The Sandlot’s idea of baseball fits snugly with its setting and baseball’s tradition of looking backward. The perpetuation of the idea that beneath modern baseball lives a game played in backyards and open lots, where the excitement of launching the ball over the fence is tempered with a bit of regret that it is now out of play. The movie’s resolution will satisfy any audience, but the details speak directly to the heart of a baseball buff.

Rookie of the Year is a vision of baseball as a means of turning personal ability into unbelievable, if fleeting, fame and fortune. The Sandlot is about the alchemy that turns a hundred small moments in a game into a singular memory. Both mythologize the Big Leagues – Henry Rowengartner reaches them in the first third of the movie, and Benny reaches them as an adult in the obligatory “Where are they now?” coda (Smalls’ fate is just as apropos and sweet).

Thomas Ian Nicholas frequently leads seventh inning stretches at Wrigley Field and had his character invoked throughout the Cubs’ 2015 and 2016 playoff and World Series runs. For its twentieth anniversary, The Sandlot cast and co-writer/director David Mickey Evans barnstormed in major, minor, and independent ballparks, signing autographs on new Blu-Ray editions. There has not been a work stoppage since the 1994 and 95 seasons. Baseball, the spectacular and the sentimental, continues.