It’s easy to get wrapped up in the theological side of The Last Temptation, so I’m going to start the second half of my review by looking at a couple of the film’s most striking formal aspects. Scorsese first worked with Michael Ballhaus when he tapped him to shoot one of the earlier, aborted versions of the film. His presence is felt throughout Last Temptation, but he’s not using the lush Technicolor style of After Hours or his Fassbinder films. The photography here comes direct from the Moroccan desert, all searing reds and sickly yellows. But his skill with the mobile camera hasn’t changed, it’s just subtler than the carnival ride of After Hours or The Color of Money. It spends much of its time floating, like a heavenly observer, and circling Jesus as He speaks. Peter Gabriel’s score is even more transcendent. Like the rest of the movie, it’s passionate but not perfect: there are a few moments of out-of-place eighties synth that break the ancient mood. But otherwise, Gabriel is very concerned about maintaining a consistent feel in his score. He draws from the instruments and rhythms of everywhere from Turkey to Egypt, creating a hybrid vision that, much like Scorsese’s stew of European art house, Hollywood B-movies, sweeping epics and intimate Neo-Realism, coalesces into something unified and new. And Gabriel’s musical influences overlap with Scorsese’s filmic influences: he says he based his editing on “the rhythms of Moroccan music.”

The film focuses on Jesus’ human side, sometimes to the exclusion of His divinity, but some scenes make the weight of Jesus’ position as God on earth felt more acutely than we’re used to seeing it. The film makes it clear that Jesus was a lot more than just a moral example. Cecil B. DeMille gave us a pious Jesus whose death is treated as more of an injustice than a seismic spiritual moment. Gore Vidal’s script for Ben-Hur tiptoed around the feelings of non-Christian viewers by playing the crucifixion as something about “the brotherhood of man.” Mel Gibson was so fascinated by the visceral experience of crucifixion that many critics found he lost the meaning behind it. In general, filmic passion plays tend to work like any other biopic, with the main difference coming from the influence of religious leaders. This film is less about telling everything Jesus did (the chronology is way too out of wack for that) than what it means. And what it means is not just another martyr, or even the founder of the world’s biggest religion. It is about the kind of impossible spiritual shift that justifies our dividing history into BC and AD. As Jesus, Willem Dafoe often talks about his plan to burn down everything his listeners know and replace it with “the world of God.” He isn’t here to preserve the status quo, of His time or ours. His words to Judas, convincing him to betray Him make that clear: “Remember, we’re bringing God and man together. They’ll never be together unless I die. I’m the sacrifice… Forget everything else, understand that.”

As for Christianity itself, that could still exist without Jesus making the impossible decision He does in the final moments of the film. While wandering the streets of Jerusalem with His “guardian angel,” Jesus sees Harry Dean Stanton as the apostle Paul, preaching all the same things he preached in the timeline where He returned to the cross. Maybe this is God’s voice intruding on the devil’s illusion, and it’s equally likely that the death of Mary Magdalen is as well. But there’s something else going on here. This Paul is a snake-oil salesman, speaking not with the possessed intensity of Jesus, but with smooth rhetorical polish and bombast (going back to that comment I made in the previous article, he sounds like Fozzie Bear.) His intentions might be good, but they’re not the same as Jesus’. “You see,” he says when Jesus confronts him, “you don’t know how much people need God. You don’t know how happy He can make them. He can make them happy to do anything. Make them happy to die, and they’ll die, all for the sake of Christ.” He’s the same as any of our modern prophets, offering answers in exchange for fanatical devotion. Scorsese says he cast Stanton to fill out the Southern Baptist side of his survey of American voices, and Stanton had already played a Baptist preacher in John Huston’s adaptation of Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood. That character was also a hypocrite and a showman, and the film features another character’s attempt to found the Church Without Christ. Well, this is what that would look like: empty solutions peddled by a huckster (assuming of course, that’s not what it is regardless). The use of Paul for this scene fits with the common conception that he invented Christianity (or at least the parts people don’t like), but it may also be a reference to something he said in the biblical text: “If in this life only we have hope in Christ, we are of all men most miserable.”

The movie never makes Jesus’ life look easy either. “God loves me. I want Him to stop,” He says, another of the paradoxes Last Temptation thrives on. Because love here is not something soft and safe, but a force of destruction necessary for total rebuilding, the ax Jesus receives from John the Baptist. It’s thorny and painful and complicated, and maybe that’s why the devil’s offer is so tempting. “Your father is a God of mercy, not punishment,” she says. But of course, He is both, and the story is all about punishment as the form mercy takes. She is offering what C.S. Lewis called “Christianity and water,” faith with all the comfort and ease, but without the pain and struggle that makes it real. The struggle Jesus deals with doesn’t quite fit with His biblical portrayal. But it is exactly the struggle of the modern viewer. Part of the film’s identification with Jesus is that He isn’t coming down to earth with a message from on high. Instead, He is something closer to a spiritual seeker, even if He has a more reliable line to God than any of us. His experiences in the monastery and the desert play out something like the modern idea of a vision quest – He is even guided by spirit animals, even though these animals are there to guide Him away from His destiny.

He struggles with His followers as well. In one of the most memorable, and sadly always-timely lines, Jesus’ condemnation of the rich inspires an angry mob. “I said Love!” He cries. “Not death!” The film revels in the contention among the disciples in a way that most adaptations gloss over. Here, they’re all a bunch of blue-collar guys (nevermind that collars didn’t exist yet) each with their own ambitions, each wondering why they gave up everything to follow their Rabbi. At the same time, the film’s Jesus is a charismatic leader who continually inspires people from all walks of life to follow Him, most dramatically portrayed in the scene of Him walking through the desert towards the viewer, His following growing through a series of dissolves. And most of them aren’t homogenous Hollywood players, but a diverse and exotic group, including the lame hoping to be healed (apparently played by real disabled actors.)

Of course, this all leads to the crucifixion, and Scorsese neither backs down from the pain and humiliation in the story that familiarity has dulled, nor takes sadistic pleasure in it. Jesus’ pain is the viewers’ pain here, as Dafoe’s frail, frequently nude body is beaten and mortified. If Jesus is humanized here, so are His tormentors. David Bowie as Pilate isn’t cruel so much as indifferent – an unusual interpretation, but one supported by the text, where Pilate is less interested in tormenting Jesus than getting His blood off his hands. Pilate is actually about as nice to Jesus as anyone else ever is, sitting beside Him to talk, like the cool teacher when a student is in trouble. He’s regretful about what he has to do, but resigned to the sacrifices he needs to make to maintain the status quo. He’s actually quite insightful in his rule-bound fatalism, in a way that underlines again Jesus’ revolutionary spirituality: “It’s one thing to want to change the way people live. But you want to change how they think, how they feel… It’s against Rome, it’s against the way the world is. And killing or loving, it’s all the same. We don’t want them changed.”

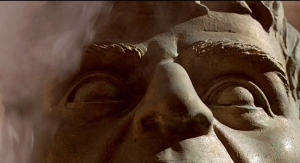

Jesus’ ritual humiliation is uncomfortably intimate, especially in a shot inspired by Bosch where Jesus carries His cross down a narrow alley while distorted, mocking faces crowd around Him, grinning with yellow teeth so that the viewer can almost feel their breath. And that’s not the end of the film’s tangibility – Ballhaus amps up the heat in the scene of Jesus’ cross being raised, directly into the blinding sun that flashes flares into our eyes. This scene often takes place on a cool night, but Scorsese puts in the heat of the midday. There is darkness at noon in the story, but Scorsese interprets that in his own way. The crucifixion includes another Ballhaus tour de force, conveying Jesus’ pain and disorientation by turning the frame sideways and dizzyingly returning it to the proper angle. It’s a trick he recycles from After Hours and that Scorsese would return to with DOP Robert Richardson in Bringing Out the Dead, though that scene will be closer to a resurrection.

What happens next, for whatever reason, is what most offended the film’s would-be censors. The Devil appears to Him, masquerading, as always, as “an angel of light,” and offers Jesus a normal life, as a husband and a father, leaving behind His calling as the son of God. This conceit powerfully demonstrates just how much Jesus sacrificed to save the souls of the world, and yet the religious leaders who could have used the film as an aid rejected it for the very reasons it was of most use to them. As far as I know, Jesus the tormented cross-maker was largely ignored, but Jesus the family man came to be seen as a blasphemy on par with Andre Serrano’s “Piss Christ.” This aspect of the controversy baffles me, but Matthew Dessem on his excellent (but defunct) Criterion Contraption blog points to a brief scene where Jesus actually has sex with Mary Magdalen while the tempting angel looks on. It may speak (or not) to the dubious shock value of the scene that I had completely forgotten it was in there. And besides that, it shows a certain failure of the modern Church’s imagination that it would seize on tawdry sexual iconography rather than the message of self-sacrifice and faith behind it. Even the mixing of sexuality and biblical stories is nothing new – the biblical epics of the fifties and sixties that the conservative Church embraced were little more than softcore dressed up with the fig leaf of biblical edification. Why else would Salome, a dancer who is mentioned for about two verses, become so central to the genre?

Regardless, it’s easy to see why Satan’s offer is so tempting. Ballhaus’s trademark lushness is back with a vengeance for this pastoral vision, with beautiful women and adorable children to stack the deck. Of course, it’s not quite right – even if you don’t know where the story is headed, the angel’s line, “There is only one woman in the world. One woman, with many faces,” should be a big red flag for feminists and Christians alike. As I said before, God makes His presence felt even in the devil’s dreamworld. In Jesus’ old age, it all falls apart, as the Romans burn Jerusalem. Scorsese returns to the transparent staginess of New York, New York and the opening of Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, turning everything outside Jesus’ window deep, unnatural red. This has the effect not just of intensifying the chaos of the scene, but of showing the breakdown of Satan’s illusion. The whole thing was just a show on the stage of Jesus’ mind all this time. That said, Jerusalem really did burn, even in this reality where Jesus chose to die. But His refusal to sacrifice Himself meant that this really was the end – it leaves no hope for His apostles, since there is nothing else for them. This is the moment when Judas returns, Jesus’ true friend who was always willing to stand up to Him, with some words that should make it clear the film never denied Jesus’ divinity. “What business do you have here? With women, with children. What’s good for men isn’t good for God!” Ease and temporary happiness aren’t enough for Jesus. He has a higher calling and He staggers out of his deathbed, calling out to God like a bizarro George Bailey that He wants to die.

He gets His wish, and returns to the cross at the moment He left it. But something is different. He is no longer in pain, but joyful. He yells out a verse from the Gospels that has always been a mystery, but that all fits together with the new story Kazantzakis and his adapters have added to the original narrative: “It is accomplished!” And then, the film recording the moment breaks down into a rainbow whirl of flashing colors. Wallflower describes it as an ascent “into the heaven of pure film,” which certainly does sound like Scorsese’s idea of Paradise. But I see it as a very Scorsesean interpretation of the scripture. St. Matthew describes the upheaval of this cosmic event causing the ground to open up, the sky to go dark, and the dead to walk the earth. The world is disrupted to its core at this total change in the spiritual landscape. Scorsese accomplishes the same effect by tearing apart the very medium the story is told in, saying in his own way that nothing can ever be the same. At first, the sound of destruction is the kind of dissonant, extended squealing that closed out Rupert’s fantasy in The King of Comedy. But then Peter Gabriel comes in with church bells ringing, and to quote Wallflower again, “the sound ascends through ululating voices into the most joyful music he ever wrote.” Or, to quote the director himself, “And now He’s made it back on the cross and He’s sort of jumping up and down saying, “We did it! We did it! I thought for one second I wasn’t going to make it – but Ididit Ididit Ididit!” Jumping up and down as He decides to die – another Gospel paradox. But that joy is palpable, just as when Scorsese repeats the line to describe his own feelings as the film was accomplished. “I thought for one second I wasn’t going to make it – but Ididit Ididit Ididit!”

Scorsese had another mammoth accomplishment ahead of him in Goodfellas. But before we dive into it, we can’t afford to overlook all the smaller projects Scorsese juggled between the inception of Last Temptation and the completion of its follow-up.

Up next: Bad, New York Stories, So On, and So Forth