Taxi Driver, much like history, repeats itself first as tragedy, then as farce. Raging Bull had already given us the tragedy, taking Taxi Driver’s examination of a lonely, macho-posturing mind and turning it on a boxer. And now, Scorsese looks again at that same loneliness and psychosis (oh, mercy, is there ever some psychosis) in an aspiring stand-up comedian. Maybe calling it a farce is putting too fine a point on it – depending on how you look at it, The King of Comedy is a comedy about sadness, or a tragedy about funny people, or both.

The sadness came from deep within Scorsese this time. After using movies as therapy for twenty years, he was still no closer to getting rid of the Travis-ness inside him. In an interview with Roger Ebert, he describes the period when he filmed Raging Bull, during his courtship and marriage to Isabella Rossellini, the daughter of his Neorealist hero Roberto Rossellini, as “a period when I thought I was happy, I’ll put it that way. A period when I thought I had all the answers.” But by the time King of Comedy came out, it was over, and even the movies weren’t safe for him. Just seeing one released by the studio Rossellini had worked with could be devastating. And all that went into the film. “There are scenes,” he told Ebert, “I almost can’t look at.”

And yet, after pouring all that rejection and loneliness and despair into Robert DeNiro’s character of Rupert Pupkin, Scorsese still made a hilarious movie, and, for this critic at least, a joy to watch. Like Pupkin, Scorsese takes “all the terrible things in my life,” and makes them funny. A lot of the credit for that goes to Jerry Lewis as Jerry Langford, a talk show host who finds himself the victim of Rupert’s rabid fandom. Scorsese considered all kinds of actors for the role: Johnny Carson, Orson Welles, Frank Sinatra. But thinking of Sinatra led him to the Rat Pack, which made him think of Dean Martin, which reminded him of Martin and Lewis et voila, Jerry Lewis got the role, and his performance really makes you wonder if he ended up playing the wrong half of the comedy team. It turns out that the Nutty Professor was born to play the straight man, and his Langford has got to be the Platonic ideal of irritation. Sitting to a candlelit dinner in Sandra Bernhard’s townhouse, wrapped in duct tape from head to toe, Jerry Lewis has a kind of grouchy magnificence that gets big laughs whenever the camera is turned towards him.

He ends up entombed in tape because he ends up on the wrong side of his biggest fan. This is something he’s used to by this point, though, hence the irritation when you might expect him to go in for full-on righteous anger. No, the film introduces Jerry during an ordinary night of filming his talk show, which ends with him being literally swarmed by his fans. He manages to cut a path through them and into his limousine, where Masha, played by Bernhard, is waiting for him. Rupert (wearing a suit that looks suspiciously like Jerry’s) swoops in to get her out, and in the process manages to get himself in. She bangs madly on the window, and the scene freezes for the credits from her point of view, showing Rupert looking down at he from inside the car, seeming more than a little like he’s gloating over his victory. He finally gets to meet his hero, and he says everything he’d rehearsed in his head a million times, even if he’s too nervous to get it all out at once. After that little lapse, though, Rupert never stops performing. DeNiro delivers every line with a cadence pitched to a live studio audience. Maybe that’s why he ignores everything Jerry tells him about how he can only get a show by starting from the bottom as a New York stand-up, and fixates on what Jerry only said in his own mind, that they’re personal friends after that one limo ride. Rupert is only suited to one thing, and that is to be Jerry Langford. The actual comedy is a distant second. Or maybe he’s just bought too much into the American Dream. He expects that every show business career is like the musicals Scorsese grew up on, where anyone with talent is one “big break” away from stardom. Rupert thinks Jerry (who he always calls by his first name) proves that’s the way the world works, since he was called up to replace another talk show host at the last minute. Never mind that Jerry only got to that point by the hard work that got him on that set to begin with.

You have to wonder why Jerry puts up with all this every single day. And it’s not just Rupert Pupkin, either. Everyone who sees him as he walks down the sidewalk treats him with the same kind of familiarity, and he’s good-humored to all of them. All that niceness can be hard to keep up, and when he lets it drop, he receives some disproportionate retribution, like when he doesn’t have time to call an old lady’s son in the hospital and she suddenly swerves from adoring him to shouting “You should only get cancer! I hope you get cancer!” That’s not just a joke, either: Jerry Lewis took the story from his own life and even directed the scene to get the timing right. But still, his character puts up with all of it. He even seeks it out – Masha points out that he likes to stay on crowded streets, and he has a long conversation with Rupert when he could have easily thrown him out, not once, but twice. Like Travis Bickle, Rupert Pupkin ends up being rewarded for his awfulness. Maybe Jerry gets punished for not being awful enough.

Rupert turns out to have something else in common with Travis, which is that he’s 100% chock-full o’ nuts. Actually, that’s not fair. He makes Travis look like the picture of well-adjusted sanity. The very next time he meets Jerry, his hero is begging him to take over the show. Except of course he isn’t. Rupert is acting all this out alone in his room, even jumping to the other side to play the part of Jerry laughing at his jokes. That’s just the beginning of our glimpse into the madness of Rupert’s private life. He has apparently made his own copy of the Langford Show studio, where he has long conversations with cardboard cutouts of Jerry and Liza Minnelli, in what has to be a reference to her professional and alleged romantic relationship with Scorsese during the filming of New York, New York. It’s hard to tell how deep the insanity goes. Rupert’s apartment looks pretty spacious, and his mother keeps yelling at him from upstairs. But later, he complains about having to pay his own rent on a “hovel”, and one of the highlights of his stand-up routine goes, “If only my mother were here. I’d say, ma, what are you doing here, you been dead for nine years!” It’s not hard to see that room as a product of the man’s delusions. But it’s pretty sad to think that, even in his fantasy, Rupert’s talking to cutouts.

The way Scorsese handles Rupert’s insanity shows the same gift for toeing the line between comedy and horror that he demonstrated in his very first film, What’s a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This? Here, as there, Rupert can pivot from Daffy Duck to Jeffrey Dahmer depending on the scene and the viewer’s interpretation. Sometimes, he’s ridiculously immature, like when he imagines his high school principal coming in as a guest on the show to marry Rupert to his old crush and publicly apologize on behalf of everyone who underestimated him. Sometimes that weird, weird apartment makes things more disturbing, as in the fantasy sequence of Rupert recording the audition tape. We see him standing in front of a giant print of an adoring crowd. The camera pulls down the long corridor behind him as we retreat into his fantasy, and the scene cuts off the audience’s echoing laughter, turning the sound into something nightmarish.

Here and elsewhere, Scorsese creates a strange world for these strange characters to work in, one that owes at least as much to installation art as it does to traditional set design. Rupert’s apartment and Jerry’s studio are done up in lurid primary colors. The offices where Rupert basically lives for the first half of the movie are blood red, bright white and deep blue, which can highlight either the movie’s light, wacky comedy or feverish, surreal horror, or both. Either way, it both separates King of Comedy from Raging Bull and connects it to the rest of Scorsese’s filmography: even in the seventies and eighties, the Age of Beige, Scorsese makes Technicolor movies.

Masha’s townhouse is grotesquely opulent, and her attempt at a romantic moment with her hostage is filmed all in different shades of gold and red. It’s not just pretty – it communicates the disconnect between Masha’s view of the situation and Jerry’s. Most comedies don’t concern themselves with the cinematography, but Fred Shuler’s work on scenes like this shows how to make photography funny.

For another example, look at the scene of the security guards chasing Rupert out of the studio. The camera remains stationary in front of an open doorway, and every once in a while Rupert runs by, and a couple guards come after him, seen in cartoony profiles. Scorsese’s discarding of his famous moving camera received a lot of criticism. Ebert called it “the kind of film that makes you want to go out and see a Scorsese movie.” But even that can be a virtue, when you see it from the right angle.

For another example, look at the scene of the security guards chasing Rupert out of the studio. The camera remains stationary in front of an open doorway, and every once in a while Rupert runs by, and a couple guards come after him, seen in cartoony profiles. Scorsese’s discarding of his famous moving camera received a lot of criticism. Ebert called it “the kind of film that makes you want to go out and see a Scorsese movie.” But even that can be a virtue, when you see it from the right angle.

Rupert keeps learning exactly the wrong lesson from everything that happens to him. He’s already ignored Jerry’s advice to start up a career from humble beginnings instead of jumping right to the end. When the studio worker Ms. Long asks for an audition tape, he spends the whole time recreating the sounds of the Langford Show. As our parent site, The Dissolve, has pointed out, he doesn’t want to be a comedian, he wants to be Jerry Langford. His fantasy about that tape isn’t just about Jerry’s admiration – the imaginary Jerry says, “I love you, but I hate you!” because Rupert is an even better Jerry than Jerry is. That isn’t his reaction, of course. It’s pretty unlikely he even heard the tape. But Ms. Long does, and she gives Rupert a bunch of helpful tips, which, as Scorsese pointed out, is a really nice thing of her to do. But Rupert doesn’t recognize that. He’s a Me Generation man through and through. He doesn’t want to get better. He wants to be patted on the back and told how wonderful he is already.

So he’s discouraged, but not enough to give up. Instead, he hauls along his old high school crush, played by DeNiro’s real life wife Diahnne Abbott, to Jerry’s house, because of course he knows where it is. Abbott had played cameo roles in New York, New York and Taxi Driver, and her performance here makes you wonder why hitching her wagon to DeNiro wasn’t enough to make her a star. She still has the same problem as previous Scorsese heroines, though, of having to convey why she puts up with a DeNiro psycho. Their relationship is about as normal as anything about Rupert. His imagined superstardom makes him act superior: he criticizes her hair and clothes, and blames her when Jerry tries to throw him out. Even better is a small role by Kim Chan as Jerry’s hilariously harried butler (“What’s wrong? Everything’s wrong.”). Jerry’s still too nice to have Rupert arrested, but not to finally speak his mind at Rupert, never mind that he doesn’t seem to understand. The Abbott character picks up a lot quicker, and decides she might as well get something out of the trip, so she sneaks a knickknack into her purse. The scene is funny, but it’s also the most painfully awkward in the movie. It’s easy to see why Rupert takes the steps he does next.

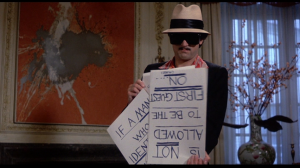

He gets in a car with his stalking buddy, now his literal partner in crime, Masha. They’re wearing giant sunglasses, though they seem to be unclear on the concept of disguise since they take them off as soon as they have Jerry in their clutches. Rupert managed to get a very fake-looking hollow plastic gun that he immediately drops when he jumps out of the car in one of the movie’s best examples of subtle slapstick. Jerry doesn’t seem to notice though, so in the car he goes. Rupert’s TV obsession is on full display when they get back to the house: he makes Jerry read the demands off of cue cars that he keeps getting out of order and dropping, and he speaks in inappropriate televisionisms like saying that Jerry should be open to “moments of sharing, and even friendship.”

The incident is also an opportunity for Masha to live out her fantasies. She literally makes him play dress up! And if there’s anything harder to make funny than photography, it’s rape, but when she switches to playing date, completely oblivious (or maybe uncaring) to how much the bound and gagged Jerry would prefer to be with literally anyone else, it’s comedy gold. Of course it’s uncomfortable, but Scorsese was onto the cringe-comedy school of Sandler and Carrell way ahead of the curve, and he does it better than just about anyone. Jerry’s savvy enough to play along long enough to get untied and runs off into the night. Both he and the scarecrow-shaped Bernhard seem to have been to the Ministry of Silly Walks, and it’s also a bit of an encore of another scene of her chasing him, with the added bonus of Masha not bothering to put her clothes back on before going out on the street in the middle of the night.

Pupkin looks around agape at Jerry’s hallowed studio, but once he gets there, he’s cool as a cucumber, not at all what you’d expect from a schlub who just decided to commit a felony. But it’s perfect for the character – he’s got stage presence, so he’ll always be smiling for imaginary cameras however he’s actually feeling. He’s kind of unreadable that way. This movie doesn’t go for the subjectivity of Taxi Driver, and as much time as we spend exploring his madness, Scorsese’s technique is very guarded. The whole movie is like the scene at the phone in Taxi Driver where the camera looks away when Travis’s pain is too much. But it’s fitting, because Rupert is a true performer, covering himself in layers of performance and persona to hide the fact that there might not be anything underneath. And he’s a surprisingly good performer, though The Dissolve was divided on the issue. He’s certainly better than the painful Jerry Langford monologue that appears on the DVD’s deleted scenes. He wasn’t kidding about making comedy from the terrible things in his life. His act, much like Scorsese’s films from the period, seems less like an attempt to entertain the audience, and more like a personal therapy session, but the audience eats it up anyway. And it might not be his own pain he’s joking about either. His childhood as a bullying victim seems likely based on his principal fantasy. But the family alcoholism seems secondhand, and if his mother really has been dead for nine years, that raises even more questions.

“Better king for a day than schmuck for a lifetime,” he says on his way out, but in the upside-down moral universe of the media world, he gets to be king for more than a day. He becomes the man of the hour in prison, he writes a bestselling book that gets optioned for a movie (this movie?) and he finally does get his dream of his own talk show. Maybe the masses think he really deserves the fame he wanted so much. Or maybe they rubberneck with shock and outrage that a man like that can get on TV, and end up giving him even more exposure. Or maybe it’s all another dream. It’s all shot on video, meaning we’re watching someone else watch TV within a movie – double-distance from reality, just like Pupkin’s on-air wedding. The Dissolve’s Tasha Robinson says, “I think Scorsese possibly tips his hand on that ending by having the camera linger just a little too long on Rupert, as the announcer’s introduction and the buzz of praise for him devolve into voices just repeating his name over and over, as if Rupert has arrived at his favorite part of the fantasy and is lingering there.” I like that, but I also like to think that Scorsese is losing the deadpan act right at the end, and goes full on for cartoony satire of the vapidity and hero worship of the television world. That comedy angle allows King of Comedy to actually, in one way, improve on Taxi Driver. The element of social satire communicates more clearly that something is very wrong here. I described Taxi Driver’s ending as a cheat, and here that element is played up. It’s obvious that we’re being cheated out of our poetic justice, and Scorsese generates the shock of anger or laughter, or maybe just Inception-top confusion. Either way, I can’t blame him. I blame the world he created, and it’s so much like our own that it’s easy to accept.

With The King of Comedy, Scorsese turned the mirror on a world that makes no sense, and it left audiences too baffled to part with enough money to make it a hit. With nothing but losses after Taxi Driver, Scorsese finally turned a profit by making a movie where the world really makes no sense without having to deal with a nervous studio breathing down his neck.

Up next: After Hours