The Color of Money seems like both the most and least likely project for Martin Scorsese at this point in his career. On the one hand, it’s a love letter to proto-New Hollywood classic, about a lonely man who needs to convince himself he really is a man. On the other, it’s a sequel from the Disney franchise factory, a Tom Cruise movie that hits all the beats you would expect from the actor at the height of his power. It’s the kind of radical departure Scorsese might have needed at this point, his first film since Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore to take him out of the City, and it doesn’t even have Alice‘s advantage of carrying over any of his usual collaborators.

But of course, that could also just be a sign that the project didn’t originate with Scorsese. The lyrics “push, pull, push, pull” appear on the soundtrack and one point, and that’s a good way of describing the way this movie works. That’s especially true of the soundtrack itself – Robbie Robertson’s selections range from classic blues-rock right out of Mean Streets to “Danger Zone”-y drum machine pop. Push-me, pull-you.

Fortunately, Scorsese wins out more often than not. Paul Newman had asked for him specifically based on Raging Bull (he wrote a fan letter to “Michael Scorsese” when it came out), so his voice had some precedence. And I do mean his voice: in Color of Money, we get to see Paul Newman and Tom Cruise, megastars with personas burned into the public consciousness, talk with Scorsese’s voice. There are times when they’re speaking from offscreen that I could have sworn Scorsese himself was reading their lines.

In The Hustler, Newman’s “Fast Eddie” Felson left pool but keeping his dignity, after George C. Scott as Bert Gordon had driven his girlfriend to suicide and threatened to run him out of pool if he ever worked for anyone else. But Felson beats the greatest pool hustler in the country and walks out of the game. When we see him again in The Color of Money, he’s not a Kerouac-ian vagabond anymore, but a rich and successful liquor salesman with plans to take his lover (Helen Shaver) on a trip to the Bahamas. He’s still in pool, but he’s taken over the Scott role, as a “stake horse” for younger hustlers – he describes it as “investing in excellence.”

He thinks he’s found some excellence in Tom Cruise as Vince, the movie’s biggest narrative engine, and its biggest problem. Scorsese and others have described the movie as a story about a bitter old man trying and failing to corrupt a young innocent. But thanks to the performances, it seemed to me more like the story of a young jackass who needs to shut up and listen to someone who knows what he’s talking about. Because make no mistake, this isn’t a movie like Collateral where Tom Cruise sheds all his Cruiseness to inhabit the character. This is Maverick with a pool cue, and thirty years later, some aspects of Cruise’s appeal seem a little baffling. He prances around the table to psych himself up, yelling like an idiot. His conversation with Fast Eddie revolves around him geeking out about an arcade game (even if it is called “Stalker” – a promotion for the Tarkovsky film, no doubt).

Cruise does combine a matinee idol personality with the Scorsese style in a way that anticipates later performances by Ray Liotta and Leonardo DiCaprio, but overall he’s a big black hole in the film, and fortunately he’s not as important as the advertising makes him out to be. Better yet, as the film wears on, it becomes clearer that he’s supposed to be at least a little hateable, especially when Newman finally beats him only to find out that Cruise let him win – Shaver even calls him “a little prick.” Still, he’s nowhere near the fountain of charm that was young Paul Newman in the earlier film, and it’s hard not to be annoyed at the presence of actors who could have played the role better, like background hustlers played by John Torturro and Forrest Whitaker. Or better yet, the movie’s biggest scene-stealer, Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio – who says a woman can’t hustle? She was Cruise’s stake horse in all but name before Newman picked them up, and she’s the closest thing Newman has to an equal sparring partner here. She’s always at least a step ahead of her man, which sometimes puts her ahead of Eddie too. She has the same toughness as earlier Scorsese women like Jodie Foster in Taxi Driver, Cathy Moriarty in Raging Bull, or Liza Minnelli in New York, New York, but this time it’s not defined as refusal to give in under a man’s domination, but a total refusal to let anyone but herself tell her what to do. And unlike Cruise, she makes it believable that she’s better off that way.

Regardless of the quality of his supporting cast, Tom Cruise is the hustler Fast Eddie is going to mold in his image, and one of the ways Color of Money benefits from its connection to the earlier movie is the disturbing ways that Felson seems to have turned into Gordon. Not only is he taking the very same percentage of all winnings, he plays around with the relationship between Cruise and Mastrantonio in ways that look queasily similar to what happened to Piper Laurie in The Hustler. But flashbacks to past trauma don’t seem to be much of an issue for Felson since he spends a lot of time hanging around Chalky’s pool hall, the scene of his past humiliations. When we first meet Felson, he seems like the man with all the answers, sitting on a pool table like a king on a throne, or a judge behind the bar.

But as Cruise refuses to play along with him, and as his time on the road reminds him how much the game has changed, his coolness falls off like a mask. The kids won’t listen to him, in much the same way as he ignored the older generation before he was a part of it. He finds out he can’t mold Cruise into the kind of hustler he wished he could have been. Well alright then. He’ll mold himself. He starts playing pool to pass the time between Cruise’s games, and keeps deeper involved. He tries to hustle a youngster played by Forrest Whitaker, who seems like a callow amateur at first before he slips into some of the same swagger Newman had shown off in the original Hustler.

Eddie walks away from the table defeated, and Michael Ballhaus’s camera looks down on him before swooping in for a closeup. It’s the opposite of the payphone scene in Taxi Driver – we don’t get to look away from his pain. And that’s just one example of the things Ballhaus does here. With the way his camera flies breathlessly through dive bars and pool halls, eavesdropping on one conversation before zipping off to another, The Color of Money is at least as much of a precursor to Goodfellas as Mean Streets had been. This is the first time I’ve ever seen the DVD copy advertise “dazzling cinematography,” and no wonder.

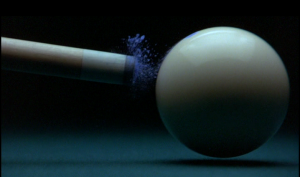

As always, he does things with color and light that no one else does – the billiard balls look like jewels or translucent candies, and he puts the camera right in the middle of the table, same as Michael Chapman did for the boxing ring in Raging Bull. Pool in this movie isn’t just two guys standing over a table. The balls are the real players, given close-ups that put them on the human scale, struggling together and skidding all over the table at lightning speed. There’s one especially electric moment where he stretches out the pool table like the church tower in Vertigo before zeroing in on the balls and cutting to a kind of shooter-cam that follows it to the moment of impact while its sound is amplified into something like a jet engine. Outside the pool table, the exteriors capture a pale wintry color in such a way that you can actually feel the cold. And in a few truly gorgeous scenes, Ballhaus reuses the gilded light that he had employed in this scene from The Marriage of Maria Braun.

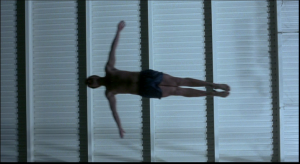

And he does ugliness just as well as beauty, filling some scenes with greenish fluorescent light that sucks all the life out of the game just like the game itself did to Eddie. He realizes he has no right to teach Cruise anymore, so he sends him off to Atlantic City on his own. Cruise isn’t having it, and in a classic Scorsese narrow stairway, under that sickly green fluorescent light, they get into a fight over Newman’s decision to dump him. Maybe it was the wrong decision, but it seems to work out for both characters – they’ll face each other at the tournament as equals. Until then, Eddie has to rebuild himself. Scorsese includes a baptismal image of him diving into a hotel swimming pool, almost silhouetted against the water.

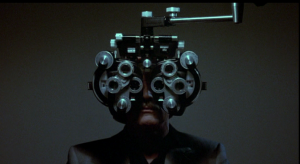

He buys himself some new eyes, hidden behind a giant metal mask of optometrist’s lenses, looking like some weird dozen-eyed monster, and comes back out with some cool tinted glasses. Slowly but surely, Ed Felson, liquor salesman and stake-horse, rebuilds himself into Fast Eddie, the most promising hustler in the field.

At the Atlantic City tournament, he ends up in a bracket against Cruise. He gets a chance to prove himself to his student, and beats him. But just before he can really celebrate the victory, Cruise and Mastrantonio show up in his room to let him know that they dumped the game. Even when Felson wins, he loses. He can’t finish the tournament with that hanging over his head. After staring at his face in the reflection off of the two-ball, he walks off the tournament. Before he can return to pool, he has to know he can beat his protégé. He tried to make Cruise into himself, and now that he’s become something else, he’s going to see if he can stand up to that in a fair fight. “It’s even,” he says, “but it ain’t settled. Let’s settle it.” The movie ends right as the game begins; we’ll never know who won. But the outcome of this one game doesn’t really matter. “What are you gonna do when I kick your ass?” Cruise asks. “Pick myself up and let you kick me again,” Newman answers. “If I don’t whip you now, I’m gonna whip you next month in Dallas. And if not then, then the month after that in New Orleans.” And then that last line as we freeze on his face and the shooter makes a crack like a gunshot: “Hey. I’m back.”

I bring this up because it’s easy to see the movie as a summation of where Scorsese was at this point in his career. He had tried to make an epic with New York, New York, and all he got out of it was an epic flop. And just when he’d clawed his way back into the movies, his next epic was blocked at every turn. So he did what Eddie does here – he rebuilt himself into what he had been before everything went belly-up, one piece at a time. By the time Color of Money was finished, Scorsese, like his character, was back. And in the next few years, he would prove it, not just with one epic, but with two, almost back to back. A towering religious statement and a generation-spanning gangster saga – the movies he was born to make.

Up Next: The Last Temptation of Christ