It’s about a guy sort of drifting around. The girl he wants, he can’t have. The girl he can have, he doesn’t want. Tries to kill the father figure of one, fails. Kills the father figure of the other. Becomes a hero.

That mechanism… of not having what you can get, and not wanting what you have… is the mechanism of loneliness. We are not lonely by nature. We make ourselves lonely. Travis makes himself lonely.

– Paul Schrader

Where do you begin with Taxi Driver? You might call it the Great American Movie, a creature even more elusive than the Great American Novel. Certainly, it shows the movies beginning to grapple with the themes that novelists had been exploring for the past century. That’s no accident, either. Paul Schrader knew the character he was creating had a history, that he was the brother of Albert Camus’ Stranger and Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Underground Man – Scorsese was even eyeing an adaptation of Notes from the Underground when Brian De Palma introduced him to the script. But Travis Bickle was something new, a tree that grew from the scarred landscape of New York in the seventies.

If you care to continue that analogy, the Stranger, and the Underground Man, Alfred Bremer’s diary and the souls of Schrader and Scorsese were all the seed, and the fruit keeps on growing right to this day. Just as Travis waits for a “real rain” to wash away all the “whores, skunk pussies, buggers, queens, fairies, dopers, junkies,” ten years later Alan Moore would create a little man in a mask in a city where “the streets are extended gutters and the gutters are full of blood and when the drains finally scab over, all the vermin will drown.” Just this year, one of the most memorable performances was Jake Gyllenhaal as another messed-up little man, foreign to human connections and reactions who came from the gutter to show a city’s true face. Just like DeNiro, he’s learned to smile in a way that doesn’t quite seem like smiling. “A story springs out of its environment,” Schrader said. “But you hope the character is strong enough that when the immediate environment changes, when the Vietnam War goes away, when Times Square gets cleaned up, the character is still valid.” Scorsese and Schrader showed us something they saw in the world, through the eyes of a “man in a metal coffin”, and it never looked quite the same again.

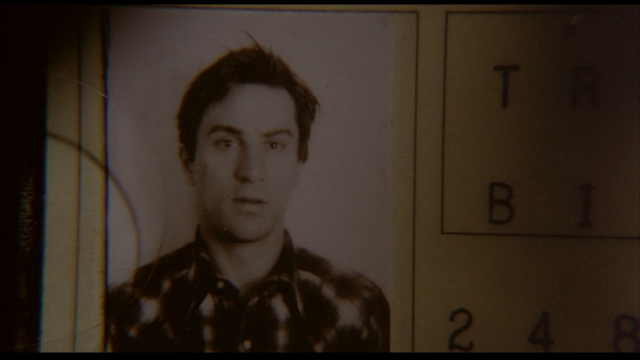

I said last week that Scorsese’s previous films had opened with a punch to the gut. Here, he’s a lot sneakier, letting Bernard Herrmann’s jazzy score creep along as a yellow taxi emerges from the steam of the sewers, looming above the camera like a horror movie monster. This is how the masterwork begins: not with a bang, but with a whimper. The film insinuates its way into the viewer’s mind, with an otherworldly, nightmarish but very real vision of New York City. Taxi Driver lets us know from the beginning that we’re looking through Travis’s eyes, as they invade our space, filling the frame so that we see nothing else, not even the rest of his face.

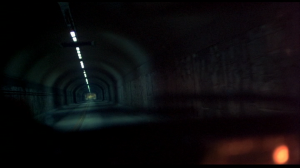

He sees New York as a neon wilderness made of streaks of light. Scorsese and cinematographer Michael Chapman distort those lights through water and glass, flooding the people on the street with unearthly light, turning filmmaking into an abstract art. Scorsese has not, to my knowledge, listed him as an influence, but Melvin Van Peebles had proven it could be done in Sweet Sweetback’s Badass Song, though Scorsese doesn’t take photography quite as far away from representation of its subject as his predecessor had. As for successors, well, what has Michael Mann done lately? Scorsese filtered the harsh reality of a city in decline through an equally-declining mental state to make an urban dreamscape that still exists in the world of films that came after him.

Chapman’s city lights, from behind the grain of the filmstock, don’t seem to illuminate anything, but instead make the night look darker and stranger. This movie could only have come from the camera technology of the seventies, and it’s the best argument I’ve seen for film over digital. Travis’s view is expressed a few scenes later as the camera slows down in a way that looks nothing like the Matrix-y effects we’re used to, but like an entire alternate reality where the atmosphere is too thick to walk at normal speed. “When a person crosses the line between fantasy and reality,” Scorsese says, “Or reality into fantasy… the fantasy is as real as the reality. It’s real. The dream is real. The paranoia is real,” and the film treats those dreams and paranoia with the same concreteness as reality itself.

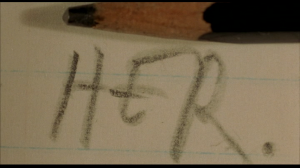

One of the filmmakers who did bring the work of the existentialists and modernists into the film world, Robert Bresson, lends a few touches to Scorsese’s own attempt. Taxi Driver shows off the minutia of Travis’s life, the details of the taxi itself, as many times and in as many different ways as Bresson showed the details of hands, newspapers and wallets in Pickpocket. The details the movie focuses on are not the ones that we would find important, but the ones that Travis does. His coworkers are less interesting to him than an Alka-Seltzer fizzing in his glass, and nothing at all can take precedence over the single word “her” in his notebook. This film is miles away from the Technicolor world of Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, but it has a hazy nightmare beauty of its own.

Taxi Driver follows Travis through his life, beginning from the moment he becomes the Taxi Driver. We never get more than a few hints of what happened before he walks into that dispatch office, but there’s an emptiness behind his smile that lets us know he has a head start on his descent into madness. “I wrote it at that way after thinking about the way they handled In Cold Blood,” Schrader says. “They tell you about Perry Smith’s background, how he developed his problems, and immediately it becomes less interesting because his problems aren’t your problems, but his symptoms are your symptoms.”

We’ll talk about those symptoms in more detail later on. In the meantime, let’s keep following Travis. He starts spying on a campaign worker named Betsy, played by Cybill Shepard as a fantasy made real, a perfect beauty but a real human being. Albert Brooks plays her coworker Tom, and he serves as kind of a counterpart to Travis, an example of the kind of person who knows how to handle his loneliness and make human connections. He brings a sense of humor and friendly chemistry to his relationship with Shepard. Travis maybe recognizes that he can never relate to Betsy the way he can, because instinctively dislikes Tom. That is, “Not that I don’t like him, I just think he’s silly. I don’t think he respects you,” because Travis can’t conceive of dealing with her as an equal. You don’t crack jokes with someone like that. You watch her and yearn from the other side of the street and buy her flowers.

Travis can almost, but not quite, carry on a conversation with her. She quotes him a line from Kris Kristofferson that calls him “a prophet and a pusher, partly truth and partly fiction. A walking contradiction,” which I would swear was a nod from Scorsese to Kristofferson for his performance in Alice if it hadn’t come from the script, written years earlier. Travis takes her too literally – he thinks she is accusing him of pushing drugs. Time doesn’t give him much clarity. He buys her the record she just quoted, and when she throws it in his face after their trip to the porn theater, he’s surprised that she already owns it. But he still manages to win her over for a cup of coffee (presumably she doesn’t recognize him from the days he had spent staring at her from his cab). In the script, Schrader says, “TRAVIS’S presence has a definite sexual charge. He has those star qualities BETSY looks for: she senses there is something special about this young man who stands before her… and then there is that disarming smile.” Of course, that doesn’t really carry over to the final product; DeNiro’s interpretation of Travis’s smile is the kind that makes you want to arm yourself. Schrader offers a better explanation a few lines later: “BETSY doesn’t quite know what to make of TRAVIS. She is curious, intrigued, tantalized. Like a moth, she draws closer to the flame.”

Travis is the opposite. He sees Betsy as a good and not a danger, but instead of drawing closer, he pulls away. “He takes her to that porn theater,” according to Schrader, “because there’s something inside him that wants to sully her and there’s something inside him that says, ‘I’m worthless, and I should be alone.’” That’s certainly a better explanation than the one Travis himself gives: “this is a movie a lot of couples come to.” He’s right of course, since two men walk out of the theater right behind him as he says this. But since they’re “buggers, queers, fairies,” he keeps his mouth shut. Betsy gives him the benefit of a doubt, but it doesn’t take long for her to realize he’s not worth the effort. But Travis, despite his perpetual self-loathing, can’t take responsibility. He keeps buying her flowers, he keeps trying to call her. He never gets out more than a halfhearted apology (“I don’t know much about movies”). He doesn’t even admit she’s mad at him: he thinks she hasn’t gone out with him again because she “had a virus or something, a 24-hour virus, you know.” Finally, he barges into her office, his true psychotic colors finally on display. “You’re gonna die in hell like the rest of them,” he shouts as Tom forces him out the door.

When Travis reiterates that sentiment a few scenes later, we get a better window into the nature of his loneliness. “I realize now how much she’s just like the others – cold and distant. And many people are like that.” We don’t get to see Travis’s life before he came to the city, or why he came there, but Robert DeNiro has said he got his accent from some Midwestern American kids he met in Italy while he was shooting 1900, and that gives a sense of the culture shock he feels in New York. He comes, presumably, from a place where people trust each other and are willing to interact and connect. Look at an earlier scene, where he asks the concessions woman at the porno theater for her name. In Travis’s native place, or time, or just his own imagined world, this would be totally normal – in my experience, he may not even have to ask. But even this most basic attempt at conversation is met with hostility, and the woman threatens to have the manager kick him out for harassing her. Travis, at least at the beginning, just wants someone to care about him, but, as the Shins would later point out, caring is creepy.

As it does to many of us, rejection sends Travis into a tailspin. Of course, his way of dealing with it is a lot less healthy than most of ours. He seems to have kept right on buying flowers for Betsy even after he stopped sending them to her, and they’re beginning to crowd him out of his apartment. Like so many school shooters, terrorists, and serial killers in the real world, Travis is confronted with his own awfulness, and decides the whole world is rotten. In between his first and second date with Betsy, Travis meets two people who will provide him with the means to cope. Senator Palantine happens to rent his cab as part of his populist philosophy, and at first he’s very willing to hear Travis’s views on the world. But when he actually hears what they are, that “You should just flush New York right down the fuckin’ toilet,” he gets nervous, rightly so since this same man will try to kill him later. Later that night, Iris the prostitute jumps into his cab, trying to get away from one of her pimps. The pimp gets to her first and tosses a crumpled dollar bill on the seat to get Travis to look the other way. He takes the money, but he holds onto it, keeping it as a memento of his failure to save her. Of course, she’ll claim later that she was just stoned. But there’s a hint of rationalization in the way she says it, the same as when she says she can quit whenever she wants. The taken fare and the missed one determine Travis’s destiny. He will kill one and “save” the other.

There’s a third fare too, Martin Scorsese himself, or, as Michael Powell described him, “that devilish actor playing the devil.” If that’s the case, Peter Boyle as Travis’s coworker “Wizard,” might be the angel for his attempt to give the budding psycho killer a little perspective. You can guess which one he listens to. Scorsese’s cameo is a memorable standalone scene that doesn’t explicitly advance the plot, but still interacts with it in intriguing ways. The man in the backseat is a psycho himself, but he keeps it under the surface better than Travis. He’s well-dressed and articulate in his own fast-talking, unfocused way. If he does go upstairs and kill his wife, he’ll probably end her life with one shot and never have to answer for it. And his fetishization of guns worms its way into Travis’s brain: he meets the dealer (who should maybe be more concerned that Travis tests the guns by aiming them at the crowd below) not long after. And the first weapon he asks for is a .44 Magnum, the same gun that his fare tells him about. “That you should see.”

After he buys the gun, Travis becomes a whole new person. His descent into madness is continuing apace. He develops rituals of violence, and Scorsese shows it visually by taking what he calls a “priest’s-eye view” of the guns at the shooting range, like bread, wine, and candles laid on the altar. Travis becomes an ascetic, like a martial artist or a monk, removing everything harmful from his body (but not his soul). He even repurposes the personal sacrament from Mean Streets, proving his strength by holding his fist over an open flame. There’s a childishness to it too, as Travis rigs up his own supercool homemade accessories (not included!) and shows off to no one. And of course he talks to no one. There’s the famous “you talking to me?” scene, but there’s another too, where he composes a speech no one will hear, or maybe a letter no one will read. He starts over partway through, as if he’s still unsure, and the camera starts over too, jump-cutting to a few seconds earlier. He makes up grandiose reasons for what he’s about to do, framing it as an act of defiance against a corrupt world, when it’s really just a symptom of it, and his own corruption too.

Up next: More Taxi Driver!