What do you do with the loneliness?

– A Mongolian fan, to Martin Scorsese

I decided to write this essay in two parts because I thought that so much has been said about Taxi Driver that the more I wrote, the better chance I had of hitting on something new. I realize now that was silly. You can never run out of things to say about Taxi Driver.

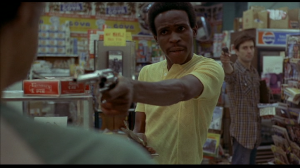

When last we left the plot of the film, Travis had been cultivating the hate and rage that had been building since before we met him. He gets a chance to let it loose when he stops in a scuzzy convenience store right as some poor schmuck is trying to rob it. It’s a little hard to root for Travis against this guy, especially after the events of the past year. Even without those biases, everything about Nat Grant’s brief performance suggests a man, a boy, really, driven to crime by no choice of his own. He’s young and black, already suggesting the deck is stacked against him, and Grant puts something in his eyes that looks guilty and terrified, of what he’s doing and maybe, what will happen if he doesn’t do it. Not that Travis notices any of that. It’s hard not to think his racism bleeds into his response, as he goes for a kill shot with no warning. It’s especially hard to ignore the connection after the very next scene, where Bickle aims his gun at the dancers on Soul Train. The cashier doesn’t come off any better either, as he goes at the kid’s unconscious, maybe dead body with a crowbar. This man shows the banality of Travis’s kind of evil, and he doesn’t just look the other way, he thanks Travis and treats him like a hero, foreshadowing what will happen when the film ends.

Travis continues stalking Palantine, and we get a vivid image of his self-destructive tendencies when he leans on his TV set until he knocks it over, destroying his one companion in his lonely room. Then he finds a different outlet for his rage when he sees Iris again, and meets her pimp, Sport. Harvey Keitel had to campaign for this role: Scorsese wanted him for the Albert Brooks part, which in the original script offered a lot more material. Actually, Schrader originally wanted Sport to be black, before he decided that it would be irresponsible to let a psychotic racist triumph over a black man. He was afraid that narrative would inspire real-life violence, which seems bitterly ironic given the film’s effect on John Hinckley, Jr. Like a surprising amount of people, Hinckley seems to have seen Bickle as a role model of badass masculinity.

It’s hard to say how much the film itself is responsible for that. Probably not much. Even on the surface level, Travis seems like a pathetic creature that it’s uncomfortable to spend time with. It’s true that Scorsese’s commitment to showing everything from Travis’s viewpoint makes it easier to take his side, but the indefensibility of his actions, and the incoherence of his justification for them, should be apparent to anyone who’s seen the film. But then, it’s pretty likely that most of his Travis’s fans haven’t seen the film. His iconic status mostly comes from the scenes of him imagining himself as a hero, taken out of context for T-shirts and tattoos. (I wrote that before seeing the YouTube comments which, as always, make it very hard to be a humanist. Expect a compilation of the “best” ones sometime tomorrow). The producers didn’t help either, since they wanted to tone down offensive language, which made Travis seem less like the racist scumbag he was imagined as. Of course, there’s more than enough actual racist scumbags out there who’d be willing to adopt him anyway. The lack of any consequences for his actions is more problematic, but we’ll cross that bridge when we come to it.

After all, that tangent has already kept us away from discussing Travis’s first meeting with Sport. As much time as Travis spends in New York’s dark underworld, he doesn’t really belong to it – Sport immediately assumes he’s a cop. Sport himself is everything Travis hates, not just because he’s a pimp and a pedophile, but because he forcefully cuts himself off from society and its expectations and never feels alienated. He’s a longhaired hippie with one effeminate painted fingernail to scoop up coke and, as Ebert pointed out, an Indian headband. Travis is a cowboy – DeNiro is actually wearing Schrader’s boots in this scene – his natural enemy. Sport doesn’t believe in the heroic myths that Travis is about to bloodily recreate; he says, “I once had a horse, on Coney Island. She he got hit by a car.”

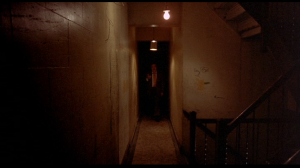

Iris leads Travis into his brothel. It’s the perfect image of the urban decay that makes him so sick, not least because it and Travis’s apartment were both shot in a real condemned building. Chapman shoots the scene as a descent into hell, through dark, graffiti-riddled caverns where the only light is dim, fiery orange. Iris doesn’t quite know what to do when Travis says he doesn’t want to make it, and she keeps trying to get him off anyway. Like all her customers, Travis is looking for a connection, but it’s not a sexual one. Instead, he asks her out to a diner, just like he did with Betsy. Travis pays for his fifteen minutes just the same – with the same wrinkled twenty-dollar bill that he’s been carrying around all this time, that he sees as the blood money for Iris’s innocence.

She meets him for breakfast at one in the afternoon (I can relate), not a hooker anymore, but a girl, without the curled hair and heels, or the pedo-baiting, stomach-baring top. Jodie Foster is brilliant, especially in this scene, building off her androgynous performance in Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. If we may talk wacky internet theories for a moment, they seem a lot like the same person – Alice’s Audrey certainly had good reasons to run away from home, and it only makes sense she’d change her name again. But, this is supposed to be a serious discussion, so I’ll put that aside. Ebert says that Travis is “like the proverbial Boy Scout who helps the little old lady across the street whether or not she wants to go,” but I think it’s more complicated than that. When Travis lets loose with what he thinks of Sport, she looks down, less like she’s ignoring him and more like she’s ashamed. Ebert also says that “a crucial…scene between Iris and Sport suggests that she was content to be with him.” Well, if the great critic was talking about the scene where she tells Sport she’s planning on leaving, and we find out that he’s been having sex with her and then neglecting her, I’ll have to respectfully disagree. Iris does give Travis some insight that he would have done well to listen to, though: “So what makes you so high and mighty, will you tell me that? Didn’t you ever try lookin’ at your own eyeballs in the mirror?” Of course, when Travis lies about working for the government, she reveals how little she really understands him: “I don’t know who’s weirder, you or me.” Travis is about to prove that he’s not just a lot weirder than her, but that his deviance is horribly dangerous.

Iris has her half-hearted confrontation with Sport, the one scene where Travis is absent, and the next we see of him is in one of the most powerful scenes of the film. He’s on the shooting range again, and every gunshot is a cut, as the camera constantly jumps towards and away from him, and shows the paper dummy being ripped, shredded, and torn.

He prepares for his last day, more ritualistic than ever. He lights his shoeshine on fire to soften it, but until he pulls out his rag and boots it looks like sacramental candles. He burns the flowers, a remnant of his old life “with” Betsy, and he shaves off all his hair but a Mohawk. Travis is anything but a punk, so this haircut means something different on him than it does on most people. Scorsese explains that “A friend of ours named Vic Magnotta, who’s now passed away, we went to NYU together, Vic and I, and then he was in Vietnam, Special Services or something, and we met with him doing some research for the film, and he talked about certain types of soldiers going into the jungle. They would cut their hair a certain way. ‘Looked like a Mohawk,’ he said. And you knew that was a special situation. Commando kind of situation. And people gave them wide berths in a way. And we thought that was a good idea.” There’s another side of it too. Travis remembers how Sport laughed at him and said, “You don’t look hip!” and immediately suspected he was carrying a piece. Travis has disguised himself to infiltrate the counterculture, and he’s distanced himself from the clean-cut kid he used to be.

He makes a token stop at Palantine’s rally, for reasons known only to him. Maybe he’s saying goodbye to his old plan. Maybe he chickened out. That night, he goes home, chugs some more pills, and murders everyone in sight. He shoots Sport right in the gut at the front door, which I like to think of a nice, if morbid, passing of the torch from Keitel to DeNiro as Scorsese’s leading man. The color had to be sucked out of this scene to get by the MPAA (there are rumors that Scorsese showed it to them so many times, with minor desaturation every time, that they just got desensitized to it). Chapman was unhappy with the decision, especially since his lurid original version is lost now, but I think it adds the right note of nightmare atmosphere to the scene. The brothel isn’t a building so much as an underworld, and the weird, pinkish-brown color scheme only highlights that. The scene is modeled on western shootouts, especially the dark, bar-set climax of Shane, but this is the opposite of the Hollywood fantasy. The murders look teeth-grindingly painful, and the brothel guards give nearly as good as they get. Scorsese strips every aspect of the gunslinger myth down to the ugliest truths, but he probably didn’t anticipate that after movies like Rambo and The Terminator, this kind of bloodshed would become compatible with rah-rah escapism to a large part of the audience. But anyone paying little enough attention to cheer for the killer should listen to the terrified Iris screaming for Travis not to kill the man who literally has his brains blown out right next to her.

The ending only makes it easier for those kinds of people to side with the psychopath. Schrader’s intentions could hardly be purer: “There was a woman who shot President Ford,” he said, “She was a little crazy. Anyway, she ended up on the cover of Newsweek, which at the time was a big deal, before the proliferation of the media we know today. And it struck me as wrong…. So I used that ending as a comment on our cultural values. You can work to cure cancer for forty years and never be acknowledged, but take a shot at the president and you get to be a hero. Because in the world of media and celebrity, there are no values. So once you’re on the cover, it doesn’t matter how you got there… He’s now a hero because he’s famous. It doesn’t mean he’s changed. He’s the same…He isn’t cured.” But for all the people who still hadn’t picked up on what Travis really was, this validates their interpretation – he even “gets the girl!” Only the smartest viewers will see the indictment of the injustice of society. The rest will see it as a just reward, or, like I did, a denial of catharsis without much in its place. Critics love to praise filmmakers who don’t “hold viewers’ hands,” but the truth is, most of us need our hands held. The ending is a minor misstep in a major classic. What Scorsese and Schrader had in mind was a fitting cap to the tale of Travis Bickle, but it didn’t quite make it to the screen. But it does seem to have inspired Scorsese to perfect the model in The King of Comedy, where Robert DeNiro again parlays crime into fame and adoration.

Before we leave, I’d like to take a look at another valuable member of the crew: Bernard Herrmann. After a long career scoring films like Citizen Kane and most of the great Hitchcock thrillers, Herrmann finished this soundtrack the day he died. He could hardly have asked for a better sendoff. He initially turned down the project, for the weirdly specific reason that he didn’t do movies about taxi drivers. But he seems to have committed to the work in the end, creating “Nightmusic” that is at once sleazy and beautiful, just like Taxi Driver and both sad and horrifying, just like Travis Bickle.

I’ll close with Schrader’s thoughts on the nature of Travis’s sadness:

“I got into screenwriting as a kind of self-therapy. When I was first writing the script, I thought it was about loneliness. What I learned while writing the script is that this is about a man who suffered from the pathology of loneliness. He wasn’t lonely by nature. He was lonely as a defense mechanism. And he reinforced his own loneliness by his own behavior. And the pathology grew until he became more and more violent. Therefore, it is a very American kind of pathology.”

After the unexpected critical and commercial success of Taxi Driver, it would seem like Martin Scorsese had no way to go but down.

Yeah, about that…

Up next: New York, New York