CHOCK FULL O’ SPOILERS

On its release, Casino got the nickname Ca-seen-it. And it’s not too hard to see why. Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: a lengthy seventies-set epic written by Nicholas Pileggi featuring Joe Pesci and Robert DeNiro as mafiosi that uses sweeping camera moves and extensive detail to let viewers into the secrets of the underworld. And not content to stop at Goodfellas, Scorsese also reaches back to Raging Bull to have DeNiro and Pesci switch roles in that film’s id-driven maniac/sensible brother figure dynamic.

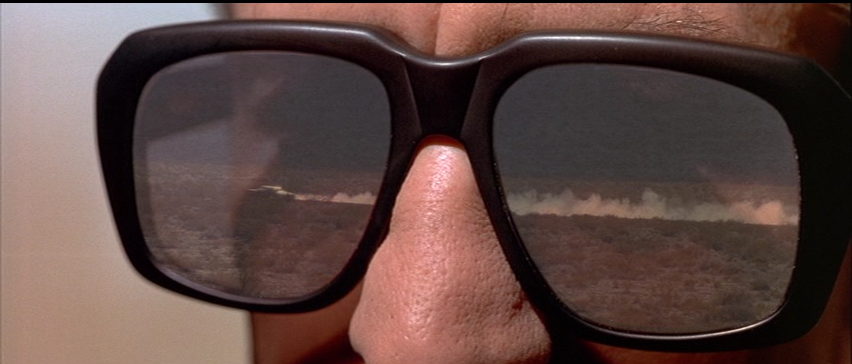

So, Casino was always going to be compared to Goodfellas, and that’s not entirely unfair. But a fairer comparison would be to the famous Copacabana scene, where Henry Hill takes the viewer behind the closed doors separating the underworld from polite society and gives them a guided tour. Casino manages to sustain that feeling for nearly an hour before it finishes scene-setting and settles into a conventional narrative, and that by itself is an accomplishment worth recognizing. As Roger Ebert says, “it makes us feel like eavesdroppers in a secret place.”

Other comparisons, though, are less flattering. Joe Pesci dies mid-sentence again, the “Layla” montage reappears scored to “Gimme Shelter,” and so on. Sometimes Scorsese manages to improve on himself: Pesci doesn’t just get cut off in the middle of a one-syllable word, the voiceover that took viewers through the whole film is abruptly interrupted (and, as I noticed the second-time through, there’s a nice bit of black comedy since his last words are “They don’t give a fuck about – ow!).

In both these films, (to say nothing of Scorsese’s other work) voiceovers like this allow the audience to hear characters’ thoughts, to let them tell their side of the story in a way that often directly contradicts what the more objective view they see onscreen. Where Goodfellas mostly gave narrating duties over to Henry Hill with occasional interruptions from Karen, in Casino DeNiro and Pesci function here as dueling narrators, each telling their own side of the story, often in ways that directly contradict each other. At any given moment, each one sees himself as right and the other as wrong. Pesci is too wild and reckless for his own good, according to DeNiro; but according to Pesci, it’s DeNiro who’s missing out on all Vegas has to offer by running the Tangiers like a business instead of running roughshod over the town.

Grant “wallflower” Nebel describes Casino and Goodfellas as, respectively, ethnography and history. One of those genres lends itself to narrative more than the other, and this means the plot of Casino has more momentum. This is obvious from an opening that literally starts off the film with a bang, as DeNiro is apparently killed in a car bombing. Where Goodfellas had opened off with the memorable but generic statement, “Ever since I can remember, I’ve wanted to be a gangster,” Casino makes the conflict much more painful and personal. “When you love someone, you’ve gotta trust them. There’s no other way. You’ve got to give them the key to everything that’s yours. Otherwise, what’s the point? And for a while, I believed that’s the kind of love I had.” The explosion immediately transitions into Saul and Elaine Bass’s credit sequence. The fire of the explosion becomes the fires of an almost medieval vision of hell, as DeNiro’s limp body floats aimlessly through. Scorsese had turned off his Catholic conscience to portray the world of Goodfellas: I had said that the lack of “moral viewpoint” killed the earlier film’s momentum. Well, good old altar boy Scorsese is back with a vengeance here. He doesn’t just evoke imagery of hell, either. Just as the Basses transitioned from a natural fire to a hellish one, they blend their vision of the inferno with the neon lights of Las Vegas. Casino begins and ends in hell.

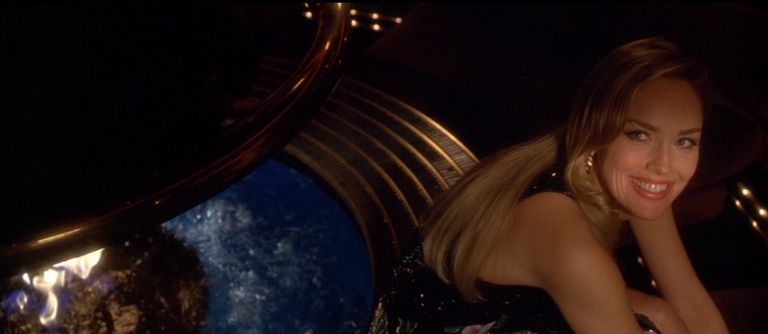

The soundtrack in these opening moments also makes it clear where the film will diverge from Goodfellas. As the car explodes, so do the voices and orchestra of Bach’s “Matthauspassion.” This isn’t going to be the documentarian Scorsese of Goodfellas, not quite – for Casino, he combines that approach with the operatic style of his previous two films. The world outside the casino might be the dreary, grimy universe of Color of Money and Mean Streets. But the minute you walk through the door, you enter a different reality. Everything seems to glow with unnatural light. Vegas has become synonymous with flashy emptiness, and Scorsese plays up those aspects of the city for all they’re worth – notice how he frames Sharon Stone in front of a window that offers a painted backdrop instead of a real view, or how he introduces her next to a fountain filled with unnaturally windex-blue water.

DeNiro as casino tycoon Ace Rothstein dresses up in ostentatious suits that even his character in New York, New York might consider a bit much, and lives in a house that would make Henry Hill dizzy (in Richard Shickel’s Conversations, Scorsese repeatedly insists that these images are actually toned down from the film’s real life inspiration!) Those images of Vegas as hell are done with exactly as much subtlety as grand opera deserves, which is to say, very little. The neon lights in the credits dissolve into and out of infernal flames, cluing the audience in before the story’s underway to what kind of world it takes place in. Characters are often framed by cigar smoke that DOP Robert Richardson turns glimmering and sulfurous.

We’re introduced to the city from a helicopter shot in the dead of night, a small circle of glittering lights surrounded by pure darkness, or maybe suspended over the darkness of the Pit. More literally, it’s the desert, which under Scorsese’s camera takes on the qualities of a mythical and moral Wasteland, an enormous graveyard in more ways than one.

The biggest difference between Goodfellas and Casino is how much of a center Casino has. Goodfellas was more or less a life story – of Henry Hill, and of the New York mafia. Conflicts came and conflicts went, but in its own way it was just as plotless as Mean Streets or Who’s That Knocking. Casino is just as expansive, but in the end it comes down to a conflict between two friends, and two ways of doing business. As Nicky Santoro, Joe Pesci represents the wild, libertarian gangster model. Rothstein says he treats Las Vegas as “the wild west,” breaking whatever rules stand between him and his payday. Rothstein is something closer to an aboveground business man – he’ll grease the wheels of corrupt politics, he’ll get involved in entrepreneurial projects to add to his income. Pesci’s performance is constantly pitched somewhere around a hundred decibels, while DeNiro maintains such an even temper that the few moments he does lash out become downright horrifying.

The prologue seems to suggest that Ace’s attempts at respectability are doomed to failure. But we discover later that he survived the explosion. Instead, Nicky’s refusal to bow to authority does him in instead. The bosses “back home,” in their shadowy lair aren’t going to let him off the hook for trying to kill their golden goose. This is another scene that shows the difference in approach between Scorsese’s two gangster epics – Nicky’s death slips past the realism of Goodfellas into the lurid world of Italian horror, as his face is covered in a red mask of blood. Dust sticks to the blood as he’s buried, making a second mask. DeNiro, meanwhile, has used his business savvy to avoid paying any consequences for his actions. He continues in the luxury he earned from the casino, totally unmoved by the death of his onetime friend.

This means the movie’s emotional center has to come from somewhere else. That would be Sharon Stone as Ginger. Even though she has far less screen time than Pseci or DeNiro, her performance is essential to the film because she’s the only who character who’s truly capable of being hurt. Nicky and Ace are, in some ways, simple characters driven by simple emotions: violence for Nicky and pride for Ace. Ginger runs the full gamut. DeNiro falls for her in a moment that emphasizes how different they are, as she reacts to an accusation of cheating by joyously throwing chips into the air. Her partner is mobbed by gamblers scrambling for free money and she gets away. It’s a clever move, but it’s also a wasteful emotional outburst, as she throws away hundreds of dollars, and continues tossing them away even after she’s made her point.

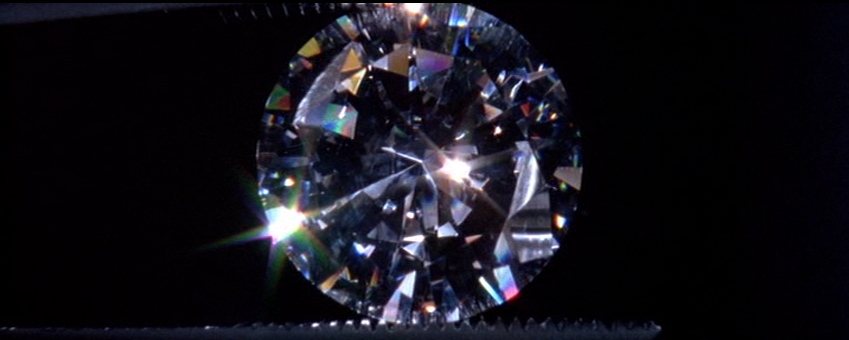

DeNiro’s pursuit of her continues as just another business transaction. He hedges his bets by waiting until their first child is born, and he quite literally tries to buy her love with clothes and jewelry so extravagantly luxurious that they pass beauty and come back around to ugliness. Even James Woods, in a brilliant performance as her ex-boyfriend Lester (seeing him repeatedly cowed by a child is one of the film’s highlights), describes entering into this marriage with another man as “the best thing you can do at this time in your life.”

Of course, that doesn’t turn out to be the case. While Ace can cut ties with Nicky if he has to, Ginger is still bound to Lester. This means she sees her husband’s true colors when he discovers she’s still seeing him, and spending Ace’s money on him. Whether to protect his assets or his relationship (which are, of course, the same thing), he calls some of his gangster buddies to beat Lester senseless. This is the pain that grounds the movie, and it only becomes more intense as Ginger descends deeper into drug abuse, alcoholism, and loathing for herself and for Ace. Stone’s performance hits the heights of operatic emotion in this film, while also avoiding the camp of Lorraine Bracco in Goodfellas. Scorsese says of her death scene, a moment that becomes intensely emotional in large part because of DeNiro’s entirely emotionless voiceover description of it, “That night, I remember Sharon Stone was trembling. She felt she had to channel the woman.”

Like Nicky, Ginger is a slave of her desires, but since she is capable of pain, she gains more sympathy. And that pain goes deeper than what we see in the narrative. Lester the pimp remembers meeting her when she was just fourteen – the implication of child prostitution is unspoken but unavoidable. And when we see her in her body post-coitally exposed, there’s a shocking number of old bruises up and down it, and Scorsese leaves it up to our imagination where she could have gotten them. That pain forgives a lot, and there is a lot to forgive: at one point she leaves her only child tied to the bed while she goes out drinking. Next to the passionless evil of Ace, Ginger’s human weakness is almost relatable.

Ace’s detachment saves him from death, though of course his moral death came years earlier. Even if he remained in the mortal world after the car bombing, the images of him floating through hell are still accurate, because his world is one completely shut off from God. Because the casino was never more than business to him, he can handle losing his license and watching the destruction of the Vegas he knew with no more than a little quiet cynicism. “It’s like Disneyland now,” he says, and before we can think the good guys have won, or that Scorsese is romanticizing the bad old days, Ace goes on to remind us that the big corporations who bought out the desert made their money on junk bonds. Vegas still belongs to criminals, just ones who belong more to Ace’s tribe than Nicky’s. And there’s more than a little hypocrisy there too. Isn’t Ace, the man who brought in French showgirls, appeared on live TV, and wore those ridiculous suits more responsible for the tidied-up Vegas than anyone?

Scorsese’s evocation of modern, tourist-friendly Vegas deserves a special place in his career of depictions of hell, as a mob of seniors, far from the glamorous “whales” of the past, crowd from the blinding light of the outside into the darkness of the casino. It’s an image that evokes his ending to Wolf of Wall Street years later, with Jordan Belfort preaching the secrets of his success to a crowd of worshipful schmucks.

That’s as worthwhile of a comparison point to Casino as Goodfellas, and it shows up Casino’s flaws as well. Both Goodfellas and Wolf end with shocking images of unrepentant evil – Ray Liotta moaning about being condemned to the life of a law-abiding American, the ghostly image of Joe Pesci shooting the audience, or the audience seeing themselves mirrored as DiCaprio’s followers. Ace Rothstein has nothing so profound to share with us. Instead, he just looks out over the mess he’s created and that others have recreated, and, with a shrug, the film ends. That’s that.

Next: