Things were not looking good for our hero when he began work on Raging Bull. He had devoted years of his life to an expensive musical flop. He had gotten addicted to cocaine. In 1978 he checked into a hospital for symptoms that he describes like an especially grisly scene from one of his movies: “Basically I was dying. I was bleeding internally all over and I didn’t even know it. My eyes were bleeding, my hands, everything except my brain and liver. I was coughing up blood, there was blood all over the place. It was a nightmare.” In the hospital, Robert DeNiro tossed the book Raging Bull on his bed, a project he had turned down ever since DeNiro brought it to his attention during the filming of Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore and asked if he wanted to film it now. Robert DeNiro knew Marty needed to make another movie to get himself back on his feet. That we got Raging Bull out of it is a nice bonus. At the time, Scorsese thought that this would be the last movie he ever made, and he intended to put everything he had into it. It would have been a fitting note for him to go out on if he had been right. Raging Bull ended up being a bit of a reunion, with Mardik Martin, Scorsese’s writing partner from Who’s That Knocking At My Door? through Mean Streets and New York, New York, contributing the first draft of a screenplay that would be punched up (so to speak) by Taxi Driver’s Paul Schrader. Michael Chapman, who had created Taxi Driver’s beautiful neon-colored look, was back too, this time working in black and white. Even his father, Charles, came in to direct a scene based on his wedding to Marty’s mother!

But Chapman’s black and white photography came about for a few different reasons. Scorsese had been vocal at the time about the deterioration of color film, and he wanted his swan song to last. It was his mentor, Michael Powell, who inspired Scorsese to do without color when he said the test footage looked wrong because DeNiro’s gloves were red. People remember the forties in black and white because that’s the medium they were preserved in, and Chapman’s old-fashioned photography recaptures the time and place. It ends up looking more than a little like an old-fashioned biopic or “boxing picture” (what do you need, a road map?), the better to highlight the shocking new direction Scorsese takes the Old Hollywood tradition in.

We open with DeNiro as Jake warming up in the ring, in slow motion and scored to opera. Pauline Kael says of a similar scene later in the movie that Scorsese is approaching self-parody, and it’s easy to see what she means. Artful self-parody, yes, but still just a little ridiculous. Once the credits have all gone up, we see DeNiro as Jake LaMotta past his prime, rehearsing in his dressing room. The film highlights the extent of DeNiro’s physical transformation by cutting from the big hunk of fat LaMotta has become to the lean, angry fighter he used to be. (By the way, everyone saying Foxcatcher is unwatchable because of Steve Carrell’s dumb-looking false nose needs to take another look at Raging Bull. Robert DeNiro might have given one of the most acclaimed performances in a career full of them here, but his prosthetics look just as bad as Carrell’s.)

This leads into the first of the film’s legendary boxing scenes, shot beautifully by Michael Chapman, focusing on the round, white lights floating in blackness and the homoerotic beauty of the challenger’s dark skin. Scorsese was determined to make the fight scenes in Raging Bull look different from every other boxing movie ever made, a wise decision since there were four others coming out that year alone. His decision to put the camera in the ring was legendary, but subtler and just as important is the subjective distortion of the ring, filmed in sets of different sizes to not just get in the ring with Jake, but inside his head as well. Scorsese says he thought Buster Keaton’s Battling Butler was the only film to really bring the potential of the medium to the boxing world, but the closest predecessor seems to be John Ford’s The Quiet Man. In a flashback to John Wayne’s accidental murder of another fighter, Ford uses the same uncomfortable close-ups and skewed perspective to get into the subjectivity of the boxing ring, and Scorsese takes these techniques even further here.

We move from there to see Jake’s life outside of the sport. We meet his first wife, who isn’t exactly the supportive figure we’re used to seeing in biopics. More important is his second wife, Vickie, played by the nineteen-year-old Cathy Moriarty. Even after appearing in a major role in a classic film, Moriarty is still mostly unknown, but her performance here makes it clear she doesn’t deserve that fate. She gives a performance full of Old Hollywood glamor, looking like she came directly from Jake’s fevered imagination, while at the same time bringing enormous strength to the woman who survived his abuse for years, and convincingly ages Vickie decades past her own age. Most important of all, Scorsese introduces us to Joe Pesci, beginning an association with Scorsese that would lead to his defining role in Goodfellas, as Joey, Jake’s brother, manager, and outmatched sparring partner. Though most of the conflict comes from the relationship between Jake and Vickie, his relationship with Joey is where the real center of the film lies. In a lot of ways, Raging Bull covers the same ground as Mean Streets, but this time we see it all from the perspective of the id-enslaved Johnny Boy character, with Pesci taking over Harvey Keitel’s role in trying to save his brother (a literal one this time) from himself.

Scorsese threw out most of LaMotta’s book in the adaptation, skipping past his formative years to get right into what the man formed into. It’s the same sensibility Schrader had brought to Taxi Driver: “They tell you about [his] background, how he developed his problems, and immediately it becomes less interesting because his problems aren’t your problems, but his symptoms are your symptoms.” So we never concern ourselves about what made Jake LaMotta Jake LaMotta, as if we could ever really know. Instead, the movie is about what it means to live that way.

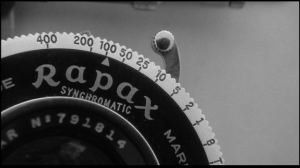

Raging Bull continues rejecting the over-explained, cradle-to-grave approach by compressing years of the most important events in Jake’s life to a single montage. Scorsese blurs the line between docudrama and documentary here, making up his own “archival footage” by cutting together still photos and home movies, all set to the music of Italian opera. The home movies are the only color footage in the film, and that, along with the lilting, serene soundtrack, make it clear this is the happiest Jake is ever going to be. They certainly show the connection between Scorsese the director and Scorsese the preservationist and analog advocate. More than nearly any other filmmaker, he is fascinated by film as a physical object, and he lovingly recreates all the little distortions and aging effects that come from consumer cameras. He recreates all the little glitches, scenes where the frame is overwhelmed with color, ones where the sprocket holes bleed into the frame, and all the scratches and smears that come from age. That fascination continues in Michael Chapman’s loving photography of the tools of photography, lingering on the reporters with their flashbulbs, and turning a photo shot into a montage of different aspects of the camera. The compression doesn’t entirely work – Jake’s first wife is pretty roughly brushed aside– but it still makes for one of the highlights of the movie.

Of course, the idyll is broken as soon as Jake speaks again. The film immediately jumps from that montage and into the middle of a fight between Jake and Joey over booking Jake outside his weight class. Both the families and all their little children are huddled in Jake’s kitchen, but he has no interest in keeping to an inside voice. All Vickie has to do is call the opponent “an up and coming fighter, he’s good looking, he’s popular” and Jake opens up on her. We’ll see as the film goes on just how fraught their relationship is – he won’t sleep with her because he’s superstitious and worse, he knows that a thug like him being married to a beautiful woman like Vickie is too good to be true. He doesn’t think he deserves her love, so he naturally assumes she’s schtupping everybody but him, and an offhanded description of a rival fighter is all the proof he needs. That’s been remarked on often. But what’s strange is how Vickie handles the situation. She knows Jake doesn’t need an excuse to turn jealous, but she gives him excuses anyway. She’s very affectionate to the other men in her life; she’ll kiss them on the face and even, as time goes on and she gets more fed up with her bullheaded husband, on the mouth. Who knows why she provokes him like this. Maybe it’s the only we she can get any attention from Jake and any excitement out of being married to him. Even in the home movies, when everything seems great for Jake, she smiles a lot less often than he does.

The idea of self-sabotage that ran through Taxi Driver is present in Jake LaMotta almost as much as in Travis Bickle. He must know that he’s only driving Vickie away with his abuse and jealousy. He takes so much abuse in the ring that you might wonder, and Scorsese does, whether he’s engaging in self-flagellation. And when he gets paid to take a dive, he doesn’t have enough integrity to throw the money away, but he has too much not to let everyone know he wasn’t really beaten. He props up the other fighter when he goes down at the first punch, and just stops fighting instead of going down. He mutilates his championship belt so he can pawn the jewels, and then finds out they’re only worth anything if the belt is intact.

Scorsese also saw Jake as an animalistic figure, and he develops that symbolically, with the title and with his leopard-print warm-up robe. Some of the first words we hear him say in private are, “this son of a bitch is calling me an animal!” It doesn’t really help his case that he threatens to kill and eat the man’s dog. And it’s not just Jake – the remarkable sound design mixes in the noise of the crowd and fighters with roaring animals. Scorsese intended the film as an act of contemplation for the viewer, a reminder that like Jake’s audience, we’re not much different from him. Or, as he quotes from the Gospel of Matthew at the end, “Whether or not he is a sinner, I do not know…All I know is this: once I was blind, but now I see.” That may have been true for Scorsese, and it may be directed at his mentor Haig Manoogian, whose memory the film is dedicated to. But for this viewer, that revelation never happened. Jake is no Travis, so Raging Bull is no Taxi Driver. It ends up being less a statement on Jake’s mental state, and more of a wallow in it.

But still, it’s a very good wallow, especially when Jake reaches the height of his success in the ring just as his personal life is falling apart. His jealousy and literal-mindedness drive him off the edge when he threatens to kill whoever has been sleeping with Vickie, and Joey finally tells him, “Well go ahead and kill everybody! Kill Vickie, kill Salvie, kill Tommy Como, kill me while you’re at it, what do I care?” To Jake that’s as good as a confession, and when Vickie says he’s right to shut him up, he’s convinced. He can’t hear her sarcasm, he takes all the wild stories she makes up to get him mad as truth. He drives his brother, the one stabilizing force in his life away, and he almost drives away Vickie too. And when he can’t bring himself to talk to Joey on the phone before he goes to defend his title, Jake goes all in for the self-punishment. And Scorsese and Schrader go in for the same images of blood as sacrament that they drew on in Taxi Driver and would return to in The Last Temptation of Christ. Jake is washed in his own blood when the sponge becomes saturated with it, and the camera lingers on a grimly beautiful shot of blood dripping off the rope.

Without Joey to keep him in line, Jake can indulge his appetites. His brother always had to hassle him about overeating, and now that he’s not around, Jake quickly balloons into a beer-gutted monstrosity. Like DeNiro’s character in New York, New York, his constant suspicion that his wife might be cheating on him doesn’t keep him from cheating on her. But then, he met her while cheating on his first wife, so that shouldn’t be a surprise. Maybe that’s why she finally moves on. Of course, with both Vickie and Joey gone, Jake, like Scorsese, has to hit rock bottom. He gets sent to jail and begins punching at the cell wall. DeNiro’s monologue here is passionate, but maybe a little too passionate. It seems less like the naturalism the rest of the performance is based on and more like the “I’M ACTING!” style of the desperate Oscar contender.

But if that scene tries too hard for an emotional payoff, Scorsese brings the tears much more successfully when Jake returns to New York to do stand up in a strip club and finds Joey working next door. Joey is totally committed to ignoring him, and Jake finally has to physically grab him to be acknowledged. Jake’s desperate for affection and forgiveness. Joey’s got none of either. DeNiro lets all his tough guy act fall aside, grabbing Pesci and begging him for a kiss. Pesci doesn’t return the hug, but just stands there pinned, and he’s obviously not going to give his brother a kiss either. That fraught relationship is where we end, with Jake in his dressing room rehearsing a monologue from On the Waterfront about another fighter, with another brother, and another betrayal. He opens by distancing himself, someone who was a contender and a champion, from Marlon Brando’s character, but the main difference seems to be what side the betrayal was on. And then, he gets up, and does the same routine he did as a boxer before he goes onstage. Sometimes, being a contender isn’t enough to save you from being a bum.  Up next: The King of Comedy

Up next: The King of Comedy