Happy endings

Anyone can see

Are for the stars

Not in the stars

For me.

Hey, everybody, Martin Scorsese made a musical! Starring Robert DeNiro and Liza Minnelli – together at last!

Oh come on, it’s not bad.

But it certainly is as bizarre as it sounds. I haven’t even mentioned that DeNiro is not cast against type at all here. If anything, he’s playing an even bigger scumbag than he did in Taxi Driver. As Jimmy Doyle, he’s a pickup artist, a volatile lover, a philandering husband, and a jealous hypocrite. He calls Francine selfish for being impregnated by him, and he gets her to marry him by threatening to commit suicide. Now, it’s not unusual to build a musical around a scumbag – Fred Astaire in Scorsese favorite The Band Wagon was pretty much Guido Anselmi without the self-awareness. But the film walks such a fine line between calling attention to DeNiro’s faults and ignoring them that sometimes it can be hard to tell how much Scorsese was aware of how unlikable his hero is. Or, to quote the man known only as The Narrator, Robert DeNiro never settles between “unpleasantly unlikable or intriguingly unlikable.” His character is the weak link in the film, without the recognizable pain that made Travis Bickle so memorable, or the total unchecked id that did the same for Johnny Boy. He’s in the middle of the road, and he only seems interesting in those brief glimpses of what Liza Minnelli’s Francine sees in him,

“Middle of the road” is a fair description of the movie’s look too. Scorsese has been very clear on his intentions for the film: “The sets would be completely fake, but the trick would be to approach the characters in the foreground like a documentary, combining the two techniques.” If that sounds like an impossible feat to pull off, the finished product won’t especially change your mind. In the beginning, especially, there’s no sense of exaggerating the model he took from. If anything, Scorsese and veteran set designer Boris Leven downplay the fakeness of their soundstage New York. The interiors of the V-Day party and the hotel Jimmy stays in look like fully-functioning buildings, and the streets still have the same traces of wear and grime that they did in Mean Streets. The sets do use bright colors, and many of them are too beautiful for this world, but they’re so lived-in, and shot with so much restraint, that they never register as fantasy. Just look at this grime-covered, bright-colored set from late in the film:

And here’s what’s behind the door:

On his introduction to the DVD, Scorsese reminisces on the musicals of his childhood, how they presented a fantasy New York where the curbs were too high and everyone was too well-dressed. But for someone like me, who doesn’t know what post-war New Yorkers wore or how high the curbs are, nothing seems off. Is it as real as Taxi Driver? Of course not, but what film is? But it rarely looks any more or less real than any of the modern comedies that fall short of reality unintentionally.

The best example would be a scene where DeNiro drives away from a motel after breaking off an extramarital affair. The sky is a flat, glowing illusion behind flat, painted hills, a shade of pink that won’t appear even on the clearest sunrise. But DeNiro’s car drives down a muddy road, strewn with dead leaves and ruts, and it breaks the illusion of Old Hollywood illusion. Charitably, we could look at this as the most literal example of the background-foreground division Scorsese talks about, but on the basic level, it shows his unwillingness to commit to the vision that obsessed him throughout the project.

The touches are still there, though. Many scenes play out in front of a painting of a cartoon skyline with lined up like a chessboard, and the use of colored lights is stagier than something like Taxi Driver. And some of the exterior scenes (in settings I’m more familiar with) make great use of matte painting, soapflake snow, and flat colors. Whether or not the sets, live up to Scorsese’s descriptions, they are a sight to behold. As the film goes on (ironically, right as reality sets in), it takes us to fantastic location like Jimmy’s purple bed in a green hotel room, or a narrow corridor covered in lights and mirrors. But compared to Scorsese’s earlier attempt in Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, or his mentor Francis Ford Coppola’s gorgeously stagy One from the Heart, this project seems strangely restrained. Even the originals, movies like Singin’ in the Rain went several steps farther than the “caricature” does.

But, like I said, it’s not bad. Scorsese’s love of Old Hollywood musicals is infectious (though there are surprisingly few musical numbers.) That’s true of the opening scene, a citywide celebration of V-J-Day, filling the city with dancing sailors and soldiers. Veteran Jimmy is prowling around looking to get laid, when he meets Liza Minnelli as Francine Evans, the spitting image of her mother, Judy Garland here. I haven’t seen Minnelli onscreen in any other roles, so I can’t say for sure whether this was always part of her persona or a choice she made for this project, but it works brilliantly either way. As I mentioned above, her relationship with DeNiro only works because she’s so convincingly in love with him that what she could possibly see in him occasionally seems irrelevant.

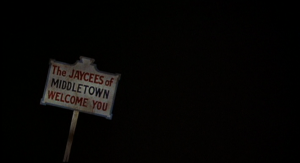

She still holds her own against him in her introduction, as DeNiro tries every line he can think of, and she’s too smart for every single one of them. And I do mean every line – he absolutely refuses to leave her alone. In the original cut, this scene alone ran for a solid hour. Even after that initial rejection (well, all of those initial rejections), DeNiro keeps finding his way into her life, since she happens to be staying at the same hotel he’s about to get thrown out of (under the assumed name of Mike Powell). Soon enough, he’s in her cab, and he’s talked her into accompanying him to an audition to play saxophone in a nightclub. She salvages his performance with her singing, but she’s off to greener pastures as the lead singer for Frankie Hart’s jazz band. DeNiro, of course, is a student of the Wiggum School of Romance (“whether you want to win a girl or crack a nut, the key is persistence”), so he runs across the country until he finds her again. He takes her off the stage, professes his love, and eventually gets a spot in the band, and even later ends up taking over. This section shows what Nathan Rabin called the film’s “truthifice if you will, or perhaps artificirealism.” They take place in a Christmas-card world where roofs are literally carpeted in snow. Minelli agrees to let DeNiro come with her in front of what’s obviously a backlit backdrop, framing the spindly the trees in front of a golden yellow glow, while the dialogue still shows the same stacatto, elliptical naturalism as it does in Scorsese’s other films.

One night, Minnelli reads him a poem she wrote about him. He yells at her to get her coat and shoes, and at first it seems like he’s going to throw another fit. He is, in a sense. She only finds out when they park in front of the justice of the peace’s office and get him out of bed that he wants to marry her. Naturally, she’s not too excited about DeNiro’s “proposal,” but he makes enough of a scene that she relents. (Apparently – in the final cut, we never see the moment she decides to go through with it, and I spent a solid twenty minutes or so not knowing whether they were married or not until another character calls Minnelli “your wife.” This is not the last time this will happen.)

The trouble in paradise (as much as their relationship is paradise, so not at all) starts when Minnelli reveals she’s pregnant. She has to stay off the road, keeping busy with studio work, while DeNiro replaces her in both the band and his bed with another singer and finally fails to keep the group afloat without her. He finds another job playing black nightclubs with an old friend played by Clarence Clemmons (he jokes that DeNiro will have to use the back entrance). DeNiro starts to develop a jealous streak after being away from Minnelli (and with another woman), and they get into a marriage-ending fight in the car, after he sees her dancing with another man, and right before she delivers their child. The final cut is missing the scene where the film confirms the marriage is broken up – the closest we get is DeNiro’s explanation for why he doesn’t see the baby: “What am I supposed to say? Hi, I’m your dad, I’m leaving now?”

They go on to success separately (at least, I know that now). He tops the charts with the instrumental he wrote for her lyrics to the title song. The night they broke up, she signed a studio contract, and in the film’s highlight, DeNiro goes to see her musical, “Happy Endings” in the theater. Scenes of the characters performing were where the original musicals cut loose into the fantasy world, and the musical-in-a-musical allows Scorsese to give up the constraints of “thruthifice” and embrace glorious, overblown artifice. Her character meets up with a Hollywood agent in a giant red room where dancers perform on a stage adorned by just a few wire frames.

She performs in a yellow room in front of floating playing cards

, and accepts an award before a long line of men in tuxes, sitting at an emerald green table and moving in perfect unison.

And of course, there’s a Busby Berkley-style overhead shot. It’s a fantasy about a theater usher’s fantasy, in the demystified fantasy of New York, New York, all coming from the fantasies Scorsese himself had in the darkened theater where he escaped the mean streets he grew up on. The only other really successful musical number is in the studio, which is slowly darkened until only Minelli’s face remains, illuminated by a spotlight. It’s fitting that it Scorsese’s attempt to blend Old Hollywood opulence and New Hollywood minimalism, that it works best when it is way off at one extreme or the other.

DeNiro sees Minnelli in person, but still from a distance, at a concert where she performs the song they wrote together, and that gives the movie its title. That song, of course, is the film’s biggest legacy, the anthem that New York City and musicians there and beyond adopted as their own. It’s fitting, given how immortal the song is and how forgotten the film is that the definitive version isn’t by Liza Minnelli, but an aging Frank Sinatra. And while the movie is of interest mostly to Scorsese completists and flop fans, its theme song shows up everywhere. And I do mean everywhere.

And deservingly so, too. It’s an epic anthem to end all epic anthems, the kind that demands to be sung along with at the top of your lungs. Those opening chords by themselves are enough to put me on a high that can last for hours, and putting that high note towards the end makes it easy to forget about the crazy, flawed, beautiful mess that surrounds it. It only makes sense that Scorsese’s grand, overreaching tribute to the musicals he grew up with triumphs most in the music created for it.

But the film was still a minor creative, and major commercial failure, and one would think Scorsese would have sworn off musicals altogether as a result. But his very next project would be the purest kind of musical – and one where the truth dominates the artifice.

Up next: The Last Waltz