I keep finding myself in a strange place as a Scorsese fan. I love his movies, but not the ones I’m supposed to. Mean Streets? Aimless and dull. Raging Bull? A dour wallow. Taxi Driver? Hey, I may be crazy, but I’m not stupid! Now, watch this space in a month or two when I gush about that Nicholas Cage ambulance driver movie that nobody remembers!

Anyway. More than any of the others, Goodfellas is a wall I keep banging my head against. For decades, the consensus has been that it’s the very best of Scorsese’s feature films. But at this point in the series, it’s the worst I’ve seen. Well, “worst” isn’t being entirely fair. As far as criticism can be objective, it’s more likely that I’m wrong than literally every other critic in the world. So my assessment of the movie has to be subjective and personal, and subjectively speaking, the movie failed to connect with me personally. I felt this way when I first saw it two years ago, and I thought a revisit from a more mature perspective would enable me to appreciate it more. Nope. If anything, I appreciated it even less.

I’ll try to spend most of this review talking about the many things the film does right, which seems more profitable. To understand why I sonly sort of like it, I may end up analyzing myself as much as the film. Apologies if I get a little navel-gazey; but the alternative would be saying the movie actually is as mediocre as I found it, and nobody wants that. Because I can understand and agree with almost everything other critics say about the film: yes, the soundtrack is incredible, yes, Scorsese manages to translate the feeling of cocaine onto film better than just about anyone else, yes, Joe Pesci is brilliant and yes, the voiceover is great. The sum of Goodfellas’ parts is great, but it’s greater than the whole. I think part of the reason I couldn’t connect with Goodfellas is that it gave me so little to connect with. Wolf of Wall Street made me laugh; Gangs of New York and Mean Streets made me cry (as did Scorsese’s model for the film, the excellent James Cagney vehicle The Roaring Twenties). Scorsese talks about Goodfellas in similarly emotional terms, but they’re vaguer and more nebulous: frustration, and nervousness, and youthful hopes. The emotion most commonly associated with criticism of Goodfellas is thrill. And it’s true that Scorsese and cinematographer Michael Ballhaus pull out every trick they know to give Goodfellas a freight-train forward momentum: the credits are even designed (by Saul Bass) to resemble a train speeding down the line. To me, though, those thrills felt just as empty as most other critics feel about the average soulless CG smashfest. Worse, all that frantic energy doesn’t keep Goodfellas, barely more than two hours, from feeling like a three-hour bum-number.

What Goodfellas seems to lack is a reason to care (or rather, for this viewer to care). My fellow soluteer Wallflower has discussed how finishing The Last Temptation of Christ gave Scorsese a newfound freedom from his themes of guilt and God and redemption. I was a little leery of that assessment — what he’s describing seemed to be Scorsese’s moral compass, which needs to be exercised more than exorcised. My reaction to Goodfellas seems to prove me right. The film is justly praised for its lack of both judgment and glorification of the mobster lifestyle. Trouble is, that leaves a film with hardly any viewpoint at all: “Here’s a bunch of stuff that happened,” Scorsese seems to be saying, “I don’t know what to make of it, but maybe you will.” The escapist fantasy of Old Hollywood gangster movies like The Roaring Twenties and the moralism of the original Scarface are both inferior to Goodfellas at representing the reality of the criminal world. But they’re also both much better as entertainment. Though Raoul Walsh and Howard Hawks were imposing their viewpoints on the material, at least it gave the films a point of view, an emotional and intellectual core that kept this viewer invested. Goodfellas doesn’t have that kind of a core statement, not on the surface level, anyway, and maybe that’s why it felt so hollow.

Some of the blame for that might be due to the core of the film’s cast, Ray Liotta. Say what you will about Gangs of New York and The Departed, but if I have to pick a guide into the underworld, I’ll take Leo over Ray any day. Liotta’s career after this makes me think I’m not alone in feeling this way, but I probably still need to explain myself. On first viewing, I thought he was the weak link, that his slimy pretty-boy persona was too annoying to anchor the film. I understand now that he’s supposed to be annoying. Real gangsters aren’t charismatic heroes like James Cagney or George Raft, after all, they’re more likely to be bottom-feeding scumbags like Henry Hill. So I made peace with Liotta’s obnoxiousness, but I still wish he could have at least been entertainingly obnoxious. I can’t tell whether his overblown, crooked way of laughing at others’ pain is brilliant or ridiculous. All I can say is that by the time I was listening to a shouting match between him and Katherine Bracco, aiming for opera but coming closer to soap opera, I couldn’t help wondering why I had to spend two hours with those two when Robert DeNiro and Joe Pesci were right over there. If I’m uncomfortable judging Liotta’s beloved performance, I’m much more comfortable dismissing Bracco. She’s a cartoon stereotype, or more accurately a caaawwwtoon steeeeereotype of a mob wife and a Jewish-American princess, shrill, shouty and nowhere near the charisma or inner strength of previous Scorsese heroines like Ellen Burstyn or Cathy Moriarty.

And now that I’ve very publicly insulted one of the most beloved movies of all time, I’d invite what few of you I haven’t scared away to join me in a more serious appraisal of the film. Like Mean Streets, it manages to keep its momentum going for a good section at the beginning before fizzling out. It’s conventional wisdom that Goodfellas’s primary ancestor is Mean Streets — even Scorsese hesitated to adapt Nicholas Pileggi’s book because he was afraid that would mean repeating himself. These early scenes suggest Scorsese was looking even further back in his career to his student film It’s Not Just You, Murray! Just as Murray talked about how successful and honest he was while the visuals show him getting smacked around by the cops, viewers of Goodfellas hear Henry Hill gushing about the initiative and glamor of the gangsters in his neighborhood while seeing them in acts of cowardly violence and thuggish intimidation.

In fact, the disconnect between Hill’s life and how he views it is a major theme in the film. The juxtaposition of his fawning description of the outlaw life with the bloody reality does a lot to undercut the romanticized concept of the mob that has been in the movies since the beginning. His behavior shows that his lifestyle really requires a certain amount of psychopathy: while his friends are putting their victims in excruciating physical and emotional pain, he treats it like the funniest thing in the world. So it should be obvious from all this that Scorsese has made the most scathing critique of American crime ever put on screen. It should be obvious. But these are all pieces of subtle subtext, that never even occurred to me before writing this piece, even after seeing the movie twice. They’re subtext, and they’re overwhelmed by the text, which is that Hill-centered viewpoint that makes for so much irony at the beginning. In Goodfellas, even more than Taxi Driver, Scorsese is so committed to making his message subtle that it’s often lost entirely.

Just as his screed against reactionary vigilante fantasies was embraced by the people he criticized, his attempt to expose the rot at the heart of gangster worship became a prime example of it. According to TotalFilm, “Henry Hill says, ‘Ever since I can remember, I wanted to be a gangster.’ Thanks to this movie so do we.” It’s easy enough to blame other viewers for the blatant misunderstanding of that ironic first line (delivered, after all, after Robert DeNiro shoots a half-dead man in his the trunk of his car), but Scorsese needs to share some of it. The movie is entirely from within the strange messed-up gangster universe, without any ray of light coming in from outside. It’s easy for viewers, like Karen Hill, to get so used to the characters’ warped ethics that they seem normal. Goodfellas never passes judgment, which is all well and good, but there’s no sense of any assessment at all within the film. The lack of moral framework didn’t just make the movie boring to this viewer: it makes Goodfellas a celebration of immorality to many viewers. Scorsese doesn’t entirely hide the contempt he holds these characters in, but his subtle commentary isn’t enough to undercut the glamor we have been taught by countless other works to see in the genre. Defenders of this film, and Wolf of Wall Street, often make the opposite mistake of the “portrayal=approval” fallacy. If Scorsese shows these scumbags being especially scummy, you’d have to be an idiot to think he glorifies them, right? But the lack of commentary means that, as far as all but the film-literate elite are concerned, he is glorifying, or at least accepting, even more awful values than your garden-variety gangster flick. Goodfellas expertly breaks down the honor-among-thieves cliche with DeNiro’s gory murder of his partners in the wake of the Lufthansa heist. But all that Eric Clapton guitar and brilliant cinematography and grotesque detail add up to nothing, because the audience is so swept up in Henry’s perspective. He keeps telling us everything is okay, and after a while, it’s hard not to believe him.

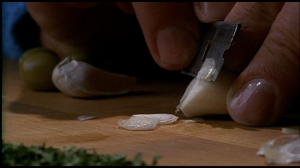

Scorsese’s indictment of gangster culture is still powerful, though, and it lays the foundation for his exploration of increasingly more socially-acceptable variations of the idea in movies like Casino or Wolf of Wall Street and Gangs of New York, which suggested that mobsters might have built the America we know today. That materialism that seems so appealing comes under close scrutiny in that famous final scene where Hill gets the standard punishment that old-fashioned code-approved gangster movies have taught us to expect. Only in this case, Hill’s punishment is to live the same kind of life most viewers live already, and while he has escaped from the underworld, he views ordinary life as a special kind of hell. Scorsese makes it painfully clear that these are people who are untouched by law and conscience. Even when Henry and Paulie are caught and sent to jail, it barely even qualifies as a setback, as their money and power allows them to turn prison into their own private resort, and their luxury is emphasized with that beautiful shot of Paulie slicing those delicate little peels of garlic.

Even in prison, they’re still somehow privileged, making homecooking and continuing their above the crowd of unwashed and unhappy humanity. Privilege is essential to Scorsese’s take on the mob: there’s the recurring idea of the “made man,” who can do whatever he wants with no consequences. It’s an amazing level of entitlement, but it’s also arbitrary. Henry and DeNiro’s James Conway can never be made, not even after they masterminded the Lufthansa Heist, because they just aren’t quite Italian enough. That same ethnic exclusiveness actually works in Henry’s favor, since he says the gangsters liked him when he first started out because “my mother was from the same part of Sicily.” It’s not hard to expand this commentary to America’s aboveground economy: Goodfellas shows the world controlled by a few powerful men, living by theft and murdering anyone in their way. At the very end, Scorsese makes sure the audience know their complicity in the depravity onscreen by going back to the very beginning of cinema and The Great Train Robbery to show Pesci’s ghost shooting a bullet right into the eyes of the audience. Dead or alive, the bad guys always win.

The film’s pure style, meanwhile, is intoxicating. Michael Ballhaus’s camera never stands still, and the lush colors that make his work so beautiful are ramped up into something lurid and sickening, bathed in the red light of blood or hell.

The shaky, dizzying scene of Henry’s father beating him is nerve-grindingly intense, and it says with just a few visuals why Henry would be so willing to put in with murderous criminals to get away from him.

There’s the wonderfully old-school highlighting of Henry’s mistress’s name on the prison sign-in sheet, and the quotes from Robert Bresson’s Pickpocket, this time with DeNiro’s hand sneaking money into someone’s pocket.

And of course, there’s the famous fourth-wall-breaking steadicam scene of Hill introducing his friends in voiceover while they greet the audience right in time with the sound of their names.

Its sister scene, the even more famous Copacabana tracking shot, illustrates what Goodfellas does so well, capturing the sense of what it means to be an insider. That’s what being a wiseguy means to Henry: the position of being inside, working with the secret powers of the city. And Scorsese makes his viewers feel like insiders as well, with the minute and perfect details of the movie’s world. This is what it’s really like, and if not, it’s hard to believe anyone could make all this up.

And while the script makes it difficult not to buy into Henry Hill’s warped worldview, the visuals constantly hint that something is wrong. It’s especially clear at the moment when Karen comes to that realization at the party with the other mob wives. Everything is done up in John Waters-ish garishness, the candy-colored clothes, the pornstar makeup and that grotesque, unnaturally blue face mask all adding up to an almost nightmarish vision.

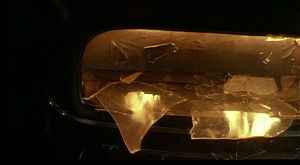

Similarly, while the classic gangster movies had shown their heroes as men of wealth and taste, living in gorgeous Art Deco mansions, it’s clear that once Henry starts selling cocaine, he has no idea how to use his money. These gangsters are high-class, but far from classy. It’s a crime that the world got Baz Luhrmann’s Great Gatsby instead of Scorsese’s: while Luhrmann embraced the excess Fitzgerald was satirizing, no one knows better than Scorsese how to make luxury look unappealing. The house Henry bought with his cocaine money is a baroque monster, colored in clashing gold and black. Look at the remote controlled sliding door covered in shards of mismatched, eye-searingly bright colored glass. It’s a profanity really: stained glass moved from the church to the home of a criminal, perverted from something beautiful into something ugly.

Even the houseplants are made of gold, the ancient symbol of greed that persists even now that money is measured in green paper. It’s present before Hill builds his fever dream house too; his previous home is wallpapered in piss-yellow.

And it’s no coincidence that the camera lingers on Henry’s fake white Christmas tree, something that all of us who grew up on Charlie Brown recognize as the ultimate emblem of consumer excess.

Even something as natural and beautiful as a newborn baby is covered in Pepto pink and laid on a rug that looks like a neon sign or a particularly bad velvet painting. Of course it is: the babies aren’t a symbol of familial affection, but crime and addiction.

That color is mirrored in Karen’s shirt, and also in the pink cadillac, a symbol of the conspicuous consumption that got its owners murdered, photographed to make the color look as sickly as possible.

That’s the biggest part of Ballhaus’ genius as a cinematographer: he knows better than anyone else how to push colors into lusciousness on one side and disgust on the opposite. He shows those skills off elsewhere, too. The unforgettable scene of the boys digging up corpses, silhouetted against a fog dyed red by their car’s taillights that swallows up everything in the color of blood.

Just as in Mean Streets, that overpowering red lights the entirety of those dark, hellish places where the gangsters do their work. Blood-red isn’t just present in the light either — it’s in the car where Henry beats up the man who raped Karen, made eye-popping against the green lawn.

And tell me you can think of anything but the unholy blood in the shot of marinara cooking.

Where Scorsese’s earlier films made blood a symbol of redemption, whether real (Last Temptation) or perverted (Taxi Driver), in this hopeless, unrepentant universe it represents the guilt itself. In Mean Streets, Charlie takes God with him everywhere — in Goodfellas, Henry’s crucifix is just a symbol of Christianity that he needs to hide to impress his girlfriend’s Jewish mother.

And now that I have turned in my Scorsese Fan card and explained why I didn’t love Goodfellas, I’ll get my friggin’ shinebox and be on my way. Hopefully I can make up for all this negativity next week when we take a look at a less-loved Scorsese film that I loved a lot more.

Up next: Cape Fear