“I’m better than you all! I can out-learn you. I can out-read you. I can out-think you. And I can out-philosophize you. And I’m gonna outlast you. You think a couple whacks to my guts is gonna get me down? It’s gonna take a hell of a lot more than that, Counselor, to prove you’re better than me! I am like God, and God like me. I am as large as God, He is as small as I. He cannot above me, nor I beneath Him be. Silesius, 17th Century.”

Like Color of Money, Cape Fear is an anomaly at this point in Marty’s career, a Scorsese studio movie, and not everyone can agree whether its followup to a classic movie is more reflective of the Hollywood reboot-reuse-recycle machine, or the filmmaker’s fascination with cinema history. Personally, I come down firmly on the second side. I don’t know if Scorsese’s intertextual obsessions were ever more present than here. A sweaty, shadowy Southern noir, the original Cape Fear is the kind of film that would attract Scorsese for reasons above and beyond a paycheck. The opening makes it clear how much a big studio remake became an opportunity for Scorsese to continue his careerlong tribute to the movies. They were created by Saul and Elaine Bass, creators of the iconic credit sequences of films like Vertigo and countless others for Hitchcock and his contemporaries. Not only that, they reuse footage shot for the John Frankenheimer classic Seconds in 1966. The music may seem familiar too, and even more Hitchcockian. That’s because it’s composed by the Master of Suspense’s favorite scorer, Bernard Herrmann, originally created for the original film and rearranged by Elmer Bernstein. Scorsese wasn’t content to just commission Herrmann’s final score: Cape Fear features the score after that. There’s more going on here than, say, the snatches of John Williams’ Superman score thrown into Superman Returns for their nostalgic weight. Bernstein turns the original thudding, melodramatic score into something that works in the modern idiom, bringing it in only to emphasize quieter moments of terror, and drawing out certain notes until it seems more like noise-rock than an Old Hollywood orchestra.

That sums up Scorsese’s approach to the film as a whole, taking something bluntly old-school and complicating and darkening it. Take for instance the other returning talent from the J. Lee Thompson version, Robert Mitchum and Gregory Peck. Now, having cameos from the stars of your source material in a cinematic redo is hardly original — at this point, it’s almost hacky. But there’s something stranger and thornier going on here. Mitchum played the bestial murderer Max Cady the first time around. Here, he’s the fatherly confidante of his nemesis, Sam Boden. Thirty years earlier, Gregory Peck had played Boden as an Atticus Finch-like pillar of legal integrity. Now, he is his Boden’s enemy, a hypocritical, grandstanding shyster defending Cady’s right to continue stalking Boden. The original followed the straightforward path of a thousand other domestic-invasion stories. Scorsese’s take manages to reach the same destination even while steadfastly refusing to take any of the same turns.

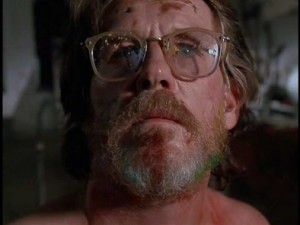

That is to say, the broad plot points are the same, but we see them entirely differently. Thompson gave us a classic struggle of good versus evil. Scorsese pits superhuman evil against human weakness, which is far more terrifying. He casts Nick Nolte in the Gregory Peck role, and while most viewers are used to seeing Nolte like this

he’s entirely credible here as the buttoned-down family man, his scraggliness tamed into a perfect Donald Trump part and hidden, Clark Kent-like, behind a huge pair of glasses. And besides, Nolte’s Boden isn’t the same kind of All-American boy that Peck’s was. He needs that little flash of madness peeking out behind his eyes. The Peck-Boden’s life was a picture of perfection ripped from Good Housekeeping until Cady showed up. The only threat was from the outside. The new Bodens are just holding together: Cady only needs a nudge to tear them apart from the inside. He’s a cheater, and he put both himself and his wife Leigh into therapy over it.

Lori Martin played Nancy as an angel child, a faultless, airbrushed miniature adult with all the sweetness and innocence of a much younger girl. Juliette Lewis plays her equivalent, Danni, as a perfectly-observed real-word teenager, replacing poise with sloppy awkwardness and perfect obedience with barely-hidden hatred. Like her father, she’s susceptible to Max Cady’s manipulation. He tears them apart from each other with a reminder of Sam’s unfaithfulness, and gets Danni on his side with the tools of seduction. He knows every detail of Danni’s inner turmoil and exactly the words she wants to hear. She has to take summer classes for being caught with weed. Max poses as her teacher and offers her a joint. He attempts to convince Danni to come with him willingly, which Scorsese somehow makes even more horrifying than outright rape. She has the same lack of common sense that anyone her age does, but she finally sees the light and turns on Cady in one of the most violently cathartic scenes in a movie full of them. Maybe that’s why Scorsese frames Cape Fear as her story. She appears less than her father, but in many ways she grows more. Cady almost takes her to the dark side before she makes the decision to reject him, and that gives her a power her father doesn’t have. That’s why, though Sam gets to have the big final battle with Max, Danni burning his face feels more like the killing blow. That moment of triumph something that the forces of nature deny her father even when he slams a boulder on the killer’s head.

Max Cady, meanwhile, is not quite so complicated. Robert DeNiro had played characters with differing levels of darkness in them, but they were all more or less redeemable, or at least human. Max Cady is none of these things, and DeNiro plays him instead as evil incarnate. He’s still understandable at some level: he has a deeply-felt grievance rather than Robert Mitchum’s arbitrary grudge. Roger Ebert even suggests that their relationship makes Boden a classic Scorsesean guilty hero, and that at some level he brought these events on himself. But let’s take another look at just what Boden is guilty of. He “killed” a report from the DA’s office that suggested that Cady’s victim had been promiscuous. In this day and age, it’s obvious that Boden made the right choice — that type of evidence isn’t even admissible any more. Given the choice between absolute morality and social obligation, Boden made the moral decision. But Cady’s mind is so deeply warped that it becomes clear he has no more justification to destroy the lawyer who failed him than the witness who incriminated him (as Boden was in the original film). When he details the suffering he experienced as the result of Boden’s “betrayal,” he focuses on one aspect of imprisonment: “ Well, what shall be my compensation, sir, for being held down and sodomized by four white guys or… four black guys?” A near-delusional level of hypocrisy should be apparent in that speech. He believes that, even though he is an especially violent rapist, he doesn’t deserve the punishment he received. And the worst and most unfair piece of that punishment, in his eyes, is to be treated the way he treats others.

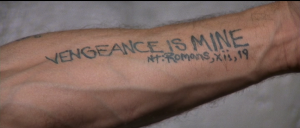

And that hypocrisy is a thread throughout Cady’s characterization. He is very fond of dropping biblical references and self-righteous proclamations into his speech. He is described as a “Pentecostal cracker,” and it’s hard not to see the character as a bit of revenge on the Bible belt fundamentalists who tried to destroy Scorsese’s Last Temptation of Christ, especially since he drives around with bumper stickers that say, “You’re a VIP on earth, I’m a VIP in heaven,” and “American by birth, Southern by the grace of God.” At first glance, this may seem to Scorsese’s most anti-religious film to date: even though it takes place in the heart of the South, the only religious references come from Cady and his corrupt lawyer. But the little Marty who wanted to be a priest isn’t totally cast aside here. The Bible didn’t shape Cady: he shapes it himself to justify the darkness in his own soul. His self-righteous rage is closer to Travis Bickle than anyone else in the Scorsese canon. Take another look at his famous biblical tattoos.

Instead of potent scriptural messages, they’re brief phrases, taken out of context to give his own instincts biblical authority: “Vengeance is mine,” taken from the Old Testament but expanded on in the New in a way that invalidates Cady’s whole mindset: “Dearly beloved, avenge not yourselves, but rather give place to wrath: for it is written, Vengeance is mine; I will repay, said the Lord.” And in some ways, Cady might be right about being God’s instrument. He tells Boden to read “the book between Esther and Psalms,” the story of Job, a good man who suffered and was rewarded for it. Cady is probably thinking of himself as Job, but it’s not hard to put Boden in that role. Cady puts him through hell and dismantles his life, but in a way that strengthens his character. We don’t see what the Bodens’ life was like after their trials and tribulations, but it is clear how Cady’s attempt to divide them forces them to work together in a way they never had previously.

Instead of potent scriptural messages, they’re brief phrases, taken out of context to give his own instincts biblical authority: “Vengeance is mine,” taken from the Old Testament but expanded on in the New in a way that invalidates Cady’s whole mindset: “Dearly beloved, avenge not yourselves, but rather give place to wrath: for it is written, Vengeance is mine; I will repay, said the Lord.” And in some ways, Cady might be right about being God’s instrument. He tells Boden to read “the book between Esther and Psalms,” the story of Job, a good man who suffered and was rewarded for it. Cady is probably thinking of himself as Job, but it’s not hard to put Boden in that role. Cady puts him through hell and dismantles his life, but in a way that strengthens his character. We don’t see what the Bodens’ life was like after their trials and tribulations, but it is clear how Cady’s attempt to divide them forces them to work together in a way they never had previously.

In character, if not in mission, Cady definitely seems like a supernatural instrument. He is seemingly omnipotent and omniscient, able to catch any tail and commit any crime in such a way that Boden will be the one paying for it. In the original Cape Fear anticipated the conservative vigilante paranoia of the seventies and eighties, portraying a system that coddles criminals rather than protecting the law-abiding. Scorsese is more cynical about where that kind of thinking leads: when Mitchum says there are “lots of ways to lean on an undesirable,” it’s pretty clear these methods are not normally used in such a morally upright context. No, it’s not the system that protects Cady: it’s something much bigger, God or the devil, or his own infernal power. Maybe that’s why he has pictures of Marvel heroes taped up in his cell: he really is superhuman.

He rolls the hitmen Boden sends to attack him just as easily as Superman might, and he gives a pseudoscientific explanation for his immense power while he drips red-hot wax onto his hand without flinching: “Let’s get somethin’ straight here. I spent fourteen years in an eight-by-nine cell surrounded by people who were less than human. My mission in that time was to become more than human. You see? Granddaddy used to handle snakes in church, Granny drank strychnine. I guess you could say I had a leg up, genetically speakin’.” Robert Mitchum was frightening, but still fundamentally understandable. DeNiro is something else entirely. He isn’t just omnipotent, he’s seemingly omniscient. He knows exactly what Danni wants to hear from him. He knows one of Sam’s coworkers was on the cusp of an adulterous relationship with him. Beyond that, cinematographer Freddie Francis films him in ways that make him look like he is not of this world. As he talks on the phone with Danni, he’s hanging upside-down like a bat from his chin-up bar. And more disturbing, the camera spins all the way around until we’re looking at Max rightside up and he tuurns into a creature from beyond the mortal realm like Marley in A Christmas Carol, “provided with an infernal atmosphere of its own. Scrooge could not feel it himself, but this was clearly the case; for though the Ghost sat perfectly motionless, its hair, and skirts, and tassels, were still agitated as by the hot vapour from an oven.” And there’s a strange element of his relationship with Boden, too, that goes beyond simple revenge. He doesn’t just want to hurt Boden. He wants to be Boden. He devoted his time in prison to acquiring the knowledge he needs to take up his occupation. When the two men finally meet, Max describes them as “two lawyers, talking shop.” There are visual cues as well: Boden enters the film in a classic Southern-fried seersucker suit. After being beaten by Sam’s thugs, Max takes to wearing an identical one. Cady’s jealousy wants deep: he believes he deserves what Sam has, he tries, in some occult way, to assimilate his enemy into himself. Talking about Danni, Max can’t help bnut mention that he had a daughter before he was put away.

DeNiro’s Southern accent may seem a little dodgy at first, mainly for the cognitive dissonance in seeing it come out of his Little Italy mouth. But as the film wears on, the musicality of his line-reading worms its way into your brain — I, for one, had a hard time not speaking the same way when I got up halfway through my second viewing. It’s also deeply seductive in a deeper sense, one that explains how he is so easily able to win over Boden’s colleague/potential affair, the courts, the woman at the airport, Danni, and even Leigh. His soul is full of primordial, bestial evil, but those same qualities give his outer self an irresistible animal magnetism. That’s wrapped up in the visual symbolism too: Jake LaMotta wears a leopard print warmup robe, and Max Cady gets stripped down underwear with the same pattern, covering the center of his animal power.

Max Cady isn’t the only aspect of the film that functions at a heightened level. In his comments on the Raging Bull piece, wallflower pointed out how essential the opera soundtrack is to suggesting the tone of the piece as a whole. Opera only makes a brief appearance in Cape Fear, when Max settles on it while scanning through his car radio, but it’s even more telling, from DeNiro’s pitched-to-the-rafters acting to the human failings treated like the fall of nations. Or maybe it’s better to look at those biblical quotes Max keeps throwing around, because Scorsese tells this story at a truly biblical scale. This becomes apparent when the action moves to the river of the title. The original film made this scene moody and dark, but pitched to the more earthbound level of its ambitions. Here, the fight isn’t just between Cady and Boden, but with the elements themselves. And even before that moment, the sense of opera begins to take over the film. Just look at the dramatic skies that overwhelm the Bodens’ little house, just after Max finds his radio station of choice:

Or even earlier, when Leigh first discovers Cady has invaded her home, he’s lit by a literal fire in the sky:

Or even earlier, when Leigh first discovers Cady has invaded her home, he’s lit by a literal fire in the sky:

Cady’s first act upon breaking into Boden’s houseboat is to cut it loose from shore. Their confrontation is heightened and complemented by the natural conflict all around them, the boat tilting and whirling in the deluge and lightning becoming more important to the lighting than the artificial light of the boat, the scenes dominated by fire and water. The violence isn’t just man on man, but the proverbial clash of the titans.

As I said, Boden begins the movie as a flawed and ordinary man, but he’s something else by the end: those Clark Kent glasses are gone. By the end of their battle, it’s been stripped down to the essentials. The boat has been shredded by the storm, and nothing is left but two prehistoric warriors attacking each other with rocks. Boden is almost ready to claim that ancient standard of manhood and land the killing blow, but at that very moment, Cady disappears, swept away by the river. Boden hasn’t earned the right to take him out of this world: Danni got to land the blow that nearly killed him because she was crawling out from under his influence, but her father doesn’t have that intimate of a connection. The supernatural instrument cannot be taken out of the world of the flesh by mortal means: he is part of the storm, so he goes back to the storm. “And he was not; for God took him.”

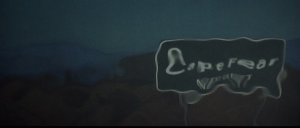

Scorsese’s hyperreal recreation of the source material is present in the film’s logic as well as its scale. There’s something deeply Freudian about Cady’s presence here: when Leigh first sees him, she has gotten up in her sleep and put on her lipstick. There’s no rational reason for her to do this: she’s surprised to see it on her face later and hurriedly wipes it off. Scorsese explains that it’s not a conscious decision: instead, in some dream-logic way, she is preparing to meet the embodiment of sex and violence. Robert DeNiro insisted on proving a man could safely hide under a moving car, but he needn’t have bothered: like a nightmare bogeyman, Max simply appears where he needs to be. See also, in the same sequence, the reflection of a highway sign for Cape Fear, that somehow isn’t a mirror image.

That’s not the only scene where the symbolism overwhelms literal realism. After his battle with Max, Sam’s hands are drenched with blood. But after he puts them in the water, they’re miraculously, baptismally spotless. The symbolism can be a bit on the nose: Max tries to seduce Danni in front of the gingerbread house, and says things like, “Maybe I’m the big bad wolf,” and “I come from the black forest.” As symbolism, this falls flat. But as Symbolism, it’s something else. Symbolism is an art movement based on the belief that everything in the physical world is a symbol for a deeper, mythic reality. These kinds of archetypes play into that reading: Max Cady isn’t just a killer, he’s The Killer; Danni isn’t just a teenager, she’s The Maiden.

And simultaneously, Danni is a real teenager, and Sam is a real father. In Cape Fear, Scorsese succeeds in the mission he failed at in New York, New York. “The sets would be completely fake, but the trick would be to approach the characters in the foreground like a documentary, combining the two techniques.” In Cape Fear, the characters and story are both symbolic and literal at the same time. Put it another way; what Thompson made blandly realistic, Scorsese makes grandly operatic; where Thompson gave us simplified types, Scorsese replaces it with complex reality. As I alluded to before, the original film is wholly uncritical of Boden’s righteous crusade to protect his family, even when he becomes desperate enough to stoop to hiring criminals. Scorsese relishes the gray areas the earlier film glossed over. Nolte’s Boden verbally and physically threatens his nemesis. He literally gets his hands dirty. While the original hopes audiences will absolve Boden of his involvement with the hitmen, this version makes him actively complicit. Cowering behind a dumpster, he watches the men he hired try to cripple Cady and instead get crippled themselves. And Cady makes him feel the weight of his decision to step outside the law, tauntingly calling out for his “couns’ler.” There are material consequences for his actions too, as the restraining order Boden tried to put on Cady gets directed at him instead. The original guides the audience to see whatever happens to Boden as no good deed unpunished: Scorsese has the guts to ask his viewers how they really feel about a man who hires criminals to do his dirty work.

Cape Fear isn’t perfect: there are plentiful moments of camp, like the cartoon sound effects Cady’s gun makes as he whips it around, or the gratuitous and unconvincing gore of the rape scene. Scorsese hasn’t improved all that much at directing horror actors since Mirror, Mirror: Jessica Lange screams about as hammily as Sam Waterston did in the earlier film. But what it does right is indelible: Ileana Douglas’ wonderfully naturalistic drunken incomprehension when she meets Max at the bar; the phone-ring that works as a jump scare for both characters and audience, as the frantic editing makes their reactions so sudden they’re almost subliminal; Max looking up at an invisible judge who could be the audience or could be God; the nuanced exploration of the trauma of testifying against a rapist, and being as the original put it, “put on trial” more than the perpetrator. In the end, the question is less, “Why would Scorsese make a big budget studio movie” and more “why not?” And our next entry should make that answer even clearer, as “selling out” gave Scorsese the opportunity to make a true epic move at a scale he never could have before.

Up next: The Age of Innocence