Sometimes when you don’t have the budget, when, or let’s put it this way, when you have limited budget, you use your imagination and your brain to do things that will come up out of nowhere, it seems, because you don’t have the money to do it, so you become more ingenious in using whatever you’ve got.

That was the thing with a lot of great B-movies in Hollywood, where they were better than the A-movies so that is sometimes, usually, I think, a lot of times, forces you, the filmmaker to use your head and fantasy and your imagination to create something because you don’t have the money — let’s say you want to have a quote-unquote, an orgy scene, you know. And you watch it in Cleopatra, let’s say, which was 50 million dollars at that time. And it’s all so elaborate and all that. And the scene with Harvey in bed with the girl in Holland that was shot, that says just as much as the Cleopatra scene with a huge budget.

Mardik Martin, Assistant Director on Who’s That Knocking On My Door

It’s become cliche at this point to list the legions of great film talent who got their start with Roger Corman’s American International Pictures. Francis Ford Coppola, Jonathan Demme, Nicholas Roeg, Ron Howard, Robert DeNiro, Sandra Bullock, Jack Nicholson (who got a producing credit on Boxcar Bertha) and, yes, Martin Scorsese.

Also James Cameron and the guy who made Sharknado, but let’s not hold that against Mister Corman, eh?

Scorsese came to the project after some success with Who’s That Knocking at My Door, and some setbacks as well– he had been fired from the set of an earlier B-movie, The Honeymoon Killers. He claims he was “shooting everything in master shots with no coverage, because I was an artist,” which is not exactly what his budget-conscious producers were looking for. He may have overcorrected a little bit on Bertha — he claims to have made storyboards of every single shot before he arrived on the set and discovered that Corman couldn’t be bothered to look at all of them. He wanted something like the sixties equivalent of a mockbuster, albeit one that came five years late — Bonnie and Clyde with more sex and violence. Scorsese delivered on that front, and though this wasn’t a passion project, it’s still every bit as good, in its own way, as his previous film.

Movies like this draw attention to a facet of Scorsese’s career that doesn’t get talked about as much as his psychological attentiveness, or his autobiographical storytelling, or his treatment of violence. Scorsese is a master craftsman, and even as an inexperienced rookie working from someone else’s script, he gives it his all. But hey, as far as that violence goes, he opens up with a literal bang, when young Bertha’s adolescent reverie is interrupted by her father’s death. He’s a crop duster who gets in an argument over his payment with a rich farmer, while Bertha and her a black farmhand named Von wait around. Then a crash, they turn around and — BOOM! There goes Bertha’s dad in a fiery explosion.

And as she cries out for him, she’s interrupted by the screen going black and the titles crashing in. So we already get to see Scorsese’s stylishness at work, but a Corman cheapie is a Corman cheapie, so we get to see the cast laid out in nice little vignettes, and wonder if this a hard-hitting work of Depression-era grit or an episode of Gilligan’s Island. Fortunately, Scorsese gets the movie back on track in a very literal way, since we move from the cast’s mugshots to some beautiful black and white footage of Bertha, now grown, riding the train to meet her lover. And then Scorsese’s name comes up and we’re back in color. I’m going to interpret that as a fitting metaphor for the heights his career was about to reach and not a vanity-based decision at all, no sir.

The lover Boxcar Bertha is going to meet is a Union man named Big Bill (they have so much in common! like alliterative nicknames!). Later, they bone. Later still, they get separated and Bertha meets a Yankee dandy at a card game who refuses to speak to hide his accent. Unfortunately, the Yank, Von, and Bill all get arrested, but Bertha seduces a guard so they can escape. To raise them some money and get rid of the car, Bertha decides they should leave it on the train tracks, and then steal the train just for the heck of it. They soon discover they can hurt the big bad train company more efficiently this way than getting beat up in strikes, so they become the notorious Barrow gang — or they have their own, non-copyright-infringing gang. There’s a nice bit of Oedipal casting too, since it gives David Carradine a chance to go up against his father John Carradine (who, to me, will always be The Secret of NIMH’s Great Owl) as a grayhaired robber baron with the glorious name of H. Buckram Sartoris

.

So with plot out of the way, let’s take another look at the style. Another one of Scorsese’s overlooked talents is his skill with period detail, recreating the past in ways that look rich and real, with just as grit around the edges as his modern-day mean streets. It’s hard to say how much of this is Scorsese’s influence and how much comes from the budget, but the past of Boxcar Bertha feels wonderfully scuzzed-up and lived-in. It is easy to see how budget constraints might have inspired Scorsese to shoot mostly in dingy, abandoned buildings, but he seems to have carried that same eye for grimy detail through his career. Either way, this ain’t no Masterpiece Theater world, that’s for sure.

Scorsese (again, maybe by necessity) also fills the film with wonderful little off the cuff details. While reading of his gang’s exploits calls himself “a pretty — petty thief.” Even better for understated humor is Bertha trying to keep her dignity and intimidate Sartoris’ guests while going commando in a dress that keeps falling off. This scene is an especially great example of Scorsese’s light touch to the proceedings. Bertha had been teaching the Yank how to speak Southern, and he drawls out “Y’all get on the floor, fast.” When that doesn’t work, he says in the very specific Noo Yawk dialect you’ll find in Scorsese films, “I said, hit the ground!” And we can see Bertha’s childlike joy at gaining power after a life of poverty, as she takes advantage of the guns she has pointed at the strike-breakers to play a game of Simon Says.

And of course, being a Bonnie and Clyde coattail-rider, there’s plenty of that same crazy chaotic New Wave editing we saw in Scorsese’s earlier films, though without the help of his career-long editor Thelma Schoonmaker, it can get even choppier and cheaper-looking than Who’s That Knocking. There’s some inspired use of close-ups when we’re introduced to Big Bill and we look right at the clubs and fists of the strike breakers waiting for their opportunity to pounce.

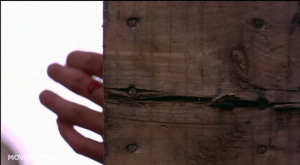

One of the most Scorsese-an images was already there when he arrived, though. Big Bill finally meets his fate when the omnipresent anti-Union goons follow Bertha and Von to his safehouse and nail him to a train. Yes, the martyr of the train workers dies crucified on the engine of his oppression. Scorsese was probably smart to deny responsibility for that one. To his credit, though, his framing gives the scene a visceral kick, as we watch the nails go into his hands from behind the board as blood sprays out.

And it does lead to a badass Blaxploitation-style shootout scene, as Von takes up a shotgun and takes out his friend’s killers, all shot in blink-and-you’ll-miss-it closeup of Von’s steely eyes and trigger finger and motherfuckers getting literally blown away. Even better, there’s an appropriately tender ending as Bertha chases after the train to retrieve Bill’s corpse, filmed in one long tracking shot until Bill is finally swept away.

Scorsese’s mentor John Cassavettes was less impressed though. “Marty,” he said after his protege had wrapped on Bertha, “ you’ve just spent a whole year of your life making a piece of shit. It’s a good picture, but you’re better than the people who make this kind of movie.” I’d say the film is far better than that, but Cassavettes was right about Scorsese being too good for the Corman factory. It was time to make a big, personal statement that would put him on the map as a filmmaking artist. And you get to read all about it, you lucky bastards, in our next stop on the Scorsese train!

Up next: Mean Streets