Why do stories always seem to find me right when I need them? Regular readers may know that I began watching The Shield in 2015 – as part of an effort to catch up on a lot of 00’s era classic television, including Deadwood – and promptly had my tiny mind blown. You may also know that a few years later, I rewatched Breaking Bad, and found a trailer for all seven seasons of The Shield on the BB season one DVD I had bought roughly around 2012. I was startled by the idea that something that had rocked the very way I see the world and brought many people I care about into my life had been following me around, waiting for me to turn back and notice it like a reverse of the Orpheus myth. Since then, I’ve had this kind of thing happen enough that I’ve decided it’s not the show, it’s me. The reason I never found The Shield until 2015 was because I didn’t know to look for it. If I had seen it before the events of 2014 had happened, I wouldn’t have understood it. Of course, it’s also possible that some force in the universe sends us things when we’re ready for them. This is the context I found The Sandman in. Midway through 2021, I started a course at TAFE, and I was given an orientation tour through the campus, and as we walked through the library, I spotted all ten volumes of The Sandman on the shelf. As I read it, I realised that if I had read this before 2021, I would not have understood it and perhaps may have even been contemptuous of it.

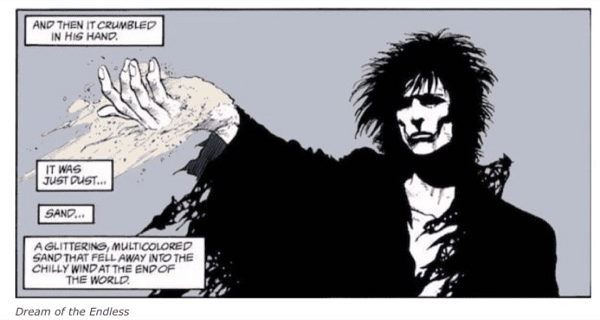

The Sandman is a comic book series about the anthropomorphic personification of dreaming. He goes by many names – Dream, Morpheus, the Lord of Dream, Oneiros, Sandman – though I prefer to simply call him Dream. He is one of the Endless, alongside his brothers, sisters, and sister-brother. Beloved Soluter ZoeZ described him as not really a character, and that quickly becomes apparent – from a dramatic structural perspective, he doesn’t so much initiate actions as he is the consequences for the actions of other people. The series opens with someone trapping him (accidentally – they were aiming for his sister Death) and he simply waits for the chance to free himself before unleashing vengeance and cleaning up the mess of his absence. Once the simple Quest narrative of his restoration of power is done, the series shifts to short stories in which its protagonists, one way or another, bring Dream upon them. In this, it resembles the structure of my beloved Cowboy Bebop, or Solute TV canon entry Columbo. Someone else incites the action, and our regular character responds. The Sandman milks the inherent iconic quality of this structure for all its worth – Dream is explicitly not a god, but in some ways he’s more powerful than that.

Wait, let me switch gears.

The Sandman is a story about stories. It took a long time for me to find that cliche annoying, but by god do I feel that now. I have always loved postmodernist deconstruction of storytelling and I likely always will, but I’ve long passed the tipping point where I feel like I understand stories well enough now, and a consequence of this is that I feel comfortable telling the difference between who is saying something of substance, who is repeating ideas they heard from somebody smarter than them, who is engaging in intellectual curiosity disguised as a story, who is telling a story with jokes in it, and who is using storytelling techniques to tell a story. The context of ZoeZ’s statement was in a reaction to me complaining about American Gods, in which I believed that author Neil Gaiman had not written a story but a love letter to the concept of stories. She pointed to The Sandman as Gaiman’s masterpiece and as something I would appreciate more, and she was right. All the things that annoyed me about even the other Gaiman stories I liked were present here, but because he actually committed to telling stories, these aspects were weaponised.

The Sandman is a story about stories. Every character we meet pulls Dream into their lives for a different reason and using a different process and thus have a different perspective of him. Some love him, some hate him, some fear him. He is punishment for one person, reward for another. What this adds up to is that, like the rest of the Endless, he is a truly universal concept. Not everyone believes in Allah, not everyone has ridden a pirate ship, and not everyone is President of the United States, but everyone will dream at some point. How someone perceives Dream largely depends on the story they’re telling and the story they think they’re telling. I was particularly struck by the issue in which Dream happens upon a convention of serial killers, and casually destroys their ability to create a romantic narrative about what they are. Dream isn’t just about literal dreaming, he’s a personification of imagination. He is humanity’s capacity to create something that didn’t exist, even if it’s just in your imagination (within Dream’s domain is a library of books that were never written). Dream, to his great surprise, turns out to be a character himself.

I cared about every issue of The Sandman, but the only one to actually make me cry was the one about Joshua Norton. I was already aware of the historical figure, and Gaiman gave me no new facts on him. Gaiman’s invention is that, following his investment that ruined him financially, Norton was watched over by Despair and then made the subject of a challenge between Dream and Desire. The idea is that Norton dreamed he was emperor with such force of will that he became not just an Emperor, but perhaps the only true Emperor the world has ever known. He was never formally recognised as Emperor, of course. He owned no land, no house, and little money or possessions. He never took a wife, though he made many offers. Nevertheless, he quickly gained the archetypal power of an Emperor; in Gaiman’s vision of the man, he is imbued with the nobility inherent to the concept, granting his citizens formal recognition not just as people who live in America but Americans; he is a friend to and champion of Mark Twain. He is not, technically speaking, an Emperor, but he fills the duties of one no matter what the expense is to him personally, and as Death points out, unlike his fellow emperors, he did it without killing a single person. Gaiman elevates him by writing a story about him, because that’s what stories do. I believe, in turn, critics elevate stories and storytellers.

I believe Dream is something of a wish fulfillment figure for Gaiman. Aside from his appearance and personality, the pleasure of empathising with Dream is that he’s an inhuman figure with no banal concerns, no worry for consequence, and no need to change. Over the course of the story’s run, however, he discovers that even he can’t escape consequence; there are stories early on in which we come back to characters whose story I had thought finished, like the return of Barbie, and Dream’s various decisions and actions snowball until the series climaxes with his death. Now, there are some works of art that function as academic discussions of an artform by leaning on a single technique so hard that it seems to become something physical that you can see in other works that use it – for example, the way Elliot Carter leans so hard on the character of individual instruments that you end up hearing it in pop songs. Initially, one would think that The Sandman draws attention to the act of creation; this is the tremendous talent of both Dream and Gaiman. Taken as a whole, however, what we’re really seeing is how to end stories. The first two-thirds of the Sandman run actually show very few beginnings of stories; the writing reminds me of early Game Of Thrones or all Tarantino in how we can feel the tremendous weight of history and backstory. And like GoT or Tarantino, this only makes it more meaningful that we see how these histories end.

Gaiman’s real brilliance is his knack for finding solutions to the problems of his plot that are surprising and yet logical. My favourite is the story of Dream going to Hell to fight Lucifer, as I genuinely found myself pondering how on earth Dream was going to deal with this, confused by what he found when he went to Hell, and delighted by the revelation that Lucifer gave up his position as Hell’s leader, resolving Dream’s issue without bloodshed and with tremendous consequence. As a work of meaning, it was profound; it draws just enough on mythology and gives us just enough clues to piece together a much larger story and series of decisions than what we see within the page, so that we can see the entire emotional arc Lucifer has gone through to come to his decision. He has become disillusioned of his responsibility and with the very concept of Hell. More importantly, it’s wildly entertaining, a solution to the puzzle that I couldn’t have seen coming. Most importantly, it was an ending; things were one way, and now they’re another. All the stories of The Sandman have that effect.

There are parts of The Sandman that I do not find resonant. There is a story about witches that includes a trans woman, and while I find the comic is deeply sympathetic to her viewpoint – I’m even willing to let go of the metaphysics of the magic in the story actively shutting her out through ‘chromosomes’, if only because it feels true to what trans people have to endure and because I admire her resolve in the face of even the moon trying to deny her womanhood – it also often has slightly too much fun drawing attention to her having a dick. There’s also a rather infamous story of a man who buys and rapes a Muse for inspiration. The thing I find fascinating about that story is that it plays out exactly the kind of thing it seems to be a warning against. Its writer protagonist is taking ideas from someone with no respect for what taking those ideas does to the source. Gaiman, in turn, casually took the concept of rape and sex slavery – something that has happened, continues to happen, and is happening right now – and used it as a plot device in his fairy tale. I have enjoyed violent media and defended its worth as both art with something to say and something entertaining to watch, but I can’t deny that making it has an effect on its real life victims. Writers often enjoy talking about creative freedom and the power of art, but I notice how often they downplay that you can be responsible for bad things too, and the thought of being a callous creative does not appeal to me.

The beginning of the end of Dream’s story is the arc known as The Kindly Ones, and it shows the fundamental basis of ending a story; mainly, that one ends a story by ceasing to create. It’s amazing how The Kindly Ones introduces no new characters or concepts at all, right from the first page; everything we see, from characters to settings, has been introduced at some point in the narrative before. The ironic thing is that doing this only serves to emphasise that the story is ending; time has passed since we saw the end of those stories and people have moved on. What we saw has truly become history. If I were to try and summarise how to end a story in a witty way, and we all know that’s exactly what I do about everything ever, it’s that one ends a story by putting the inciting incident in the past. Draw all the consequences out of it, stopping when they’re all done. Gaiman said that the story of The Sandman was Dream learning that he must change or die and making his choice; I was deeply annoyed at first when the introduction to The Kindly Ones spoiled the answer, but it turns out they are one and the same. He is no longer the person who would do what he did at the start. His actions are in the past and new actions have replaced them.

The thing postmodernism gets dinged for most is its uselessness outside the writing or reading of stories (“That sounds like a really good film… for filmmakers.”). But good postmodernism isn’t just about books and movies and cartoons and shit, but the narratives people craft for themselves. There’s a guy who gets up every day calling himself a husband and father and, unbeknownst to him, is ruining the lives of himself and everyone around him because he never actually put any thought in how to achieve that. There’s a woman who fell into a pyramid scheme because it played off her aspirations to be a successful, empowered businesswoman and she never learned more than the basic archetypes people around her could fall into. In this case, I can see how many of my problems – emotionally, anyway, with other things stemming from that – stemmed from not knowing how to end stories or how to put an inciting action into the past. The Sandman shows one way to do that, over and over and over.