The mystery surrounding “Ode to Billie Joe” has often overshadowed the song itself.

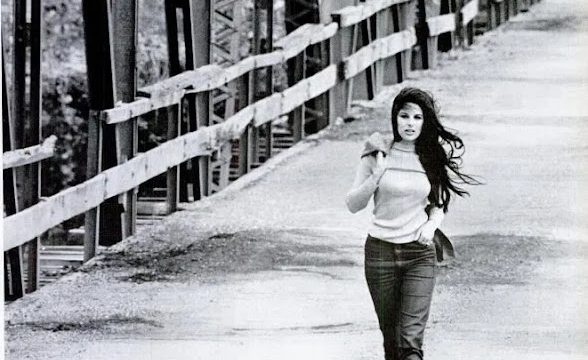

We know who Layla was, more or less who walked into the party like he was walking onto a yacht, and I’m pretty sure most people in the music industry have a shortlist for the man who washed his hands clean of Alanis Morrisette. But singer-songwriter Bobbie Gentry hasn’t even officially appeared in public since 1982, and she hasn’t said a damn word about what, exactly, happened up on Choctaw Ridge.

It’s the kind of thing I’d normally call a pity, because the song itself deserves to be talked about on its own merits, but in this case, the mystery of the narrative is as tightly wound into the song as the haunting strings that slide across its opening notes.

Technically the song is great: perfect rhymes, top-notch musicianship, and an arrangement as sparse and haunting as the song’s lyrics. Gentry’s voice is reedy and hesitant on the high notes, and gravelly and serious on the low ones.

“Ode to Billie Joe” is a small town song, as carefully crafted as a Raymond Carver story. Gentry uses sparse, evocative details, making sure we can feel the dust in the oven-hot air and see the narrator’s brother reaching for another slice of apple pie.

The narrator is a young woman, young enough to still be living at home, but old enough for some independence, and old enough to have her own inner life and her own secrets. But the truth is that no one can keep secrets easily in a town as small as hers. Small town life frames “Ode to Billie Joe”; death, marriage, chores. Gentry even had a specific bridge in mind — where the Tallahatchie River wasn’t deep, but the current was strong — and that specificity informs the song from start to finish.

Gentry said in interviews that she wanted to show unconscious cruelty; Mama and the narrator each seem oblivious to the other’s grief, and the central dinner table conversation treats the suicide of a young man as just another piece of local gossip. There’s also a current of disconnection here; Mama does wonder why the narrator isn’t eating, but she’s not able — or willing — to put two and two together, even when the young preacher has recognized her daughter with Billie Joe on the bridge. (Gentry was aware of that too; she said they had both “isolated themselves in their own personal tragedies.”)

Gentry told interviewers that she did have a specific object in mind that got thrown off the bridge, but she never told what, and she didn’t think that was particularly relevant, anyway. The one hint she gave — that it might have been an engagement ring — was contradicted by the film adaptation, which she wrote music for. There have been dozens of theories, of course: a draft card, LSD, flowers, an actual baby. (An actual baby.) But I’m inclined to agree with Gentry that the object itself isn’t particularly important. To get too hung up on what went over that bridge is to make the same mistake as the narrator and her family, focusing on minutiae at the expense of the human hearts involved. Whatever drove Billie Joe McAllister to the bridge, it’s nothing that can be summed up with a single object. Nothing ever can.

It feels a bit rote to say this after every piece, but it also feels necessary: If you’re in the US, the national Suicide Prevention Line is 800-273-8255, and will soon be 988; as the little cards I used to hand out at an old job said, you don’t have to be in crisis to call the crisis line. If you’re asking yourself if you’re bad enough, just freaking call. Please.

Here are some tips for suicide prevention, because it’s important to know the signs (though some suicide deaths are not preceded by warning signs at all).

On a lighter note: “Ode to Billie Joe” was so massive it got parodied by Bob Dylan and on Saturday Night Live in the 2000s.