The iconic repeated image of a Michael Mann film is a man with a gun, which sounds like a ridiculous statement–men and their guns have been an iconic part of many if not most films, going back to The Great Train Robbery. Watch a few Mann films, though, and you can see the difference between his men with guns and all the others. The men have their spines straight, arms at near full extension with the shoulders locked, eye/front sight/rear sight aligned. They move with their upper torsos steady, like a turret. Very simply, a Mann character looks, moves, and acts like a man who is actually going to fire a gun. They look like this because even if the script requires them to do nothing more than draw a gun, Mann puts them through weeks of training with live ammunition, so they learn how to hold and prepare themselves for the act of firing. (Robert deNiro and Tom Cruise are apparently the best shots.) If you’ve ever shot before, you can see that Mann’s actors are among the very few who look like if they pull the trigger, the gun won’t actually go flying out of their hands.

If that’s all there was to Mann, he’d be a great choreographer of action, which would still be something pretty darn impressive in cinema. What makes him a great director in the classical sense of the word, someone who has a unifying vision expressed in cinema with a depth comparable to Kurosawa, Kubrick, or the Coens, is that what’s behind how he shoots men with guns extends outward to all his characters, to his stories, to the dialogue and music and imagery of the films. In a word, Mann’s films are about professionals; the most common professions in the Mann canon are detectives and thieves (those professions are the titles of Heat and Thief; Public Enemies, Miami Vice, and Manhunter are about them too), but there are also assassins and cabdrivers (Collateral), scientists and journalists (The Insider), soldiers and hunters (The Last of the Mohicans), hackers (Blackhat), and even fighters (Ali).

To become a professional (one isn’t born professional, one becomes it, and more on this at the end) means to master a specific discipline–a specific set of skillz, if you will. It means to be supremely competent at something, not the world’s champion; professionalism isn’t about competition. Professionals aren’t rewarded by victory or even wealth (Neil McCauley’s empty home and Vincent Hanna’s TV set convey that so well), but by the reward of knowing that when you’re tasked to do something, that shit gets done. That’s something crucial in Mann’s films, because it means professionals can recognize and respect each other, even when they’re, y’know, trying to kill each other. Professionals are limited, necessarily so; it takes a long discipline to acquire those skills and to embody them, and will only exercise those skills in a disciplined manner. It’s about doing what’s necessary, no more or less; to use William Burroughs’ phrase, professionals do their work and go.

All Mann’s films have their characters display the attitudes and details of professionals. Performances in Mann’s films are reserved, direct, and filled with the physical and mental details of the profession, and Al Pacino is absolutely not an exception. He gets caricatured as Shouty Pacino, and often he deserves that, but at his best, Pacino explodes entirely in character. When Hanna yells, it’s not like the volcanic rage of Michael Corleone or the high-quality theatrical ham of The Devil’s Advocate. (mmmm. . .ham) It’s one notch below full volume (it goes to 9), and his face tells us that Hanna is fully in command of what he’s doing, like a professional. (When he comes back to his hotel room to find his stepdaughter has slashed her wrists, he’s briefly not in command, and it’s a completely different look.) It’s a technique, something he does (and something actual detectives do) to keep his informants and suspects off-balance.

Go through any of Mann’s films and you can see all the details of professionalism; you can see how the actors aren’t just playing a character, they’ve come to embody the skills of a profession. Film is less forgiving of body language than any other medium, so it’s absolutely necessary that Mann’s actors train in their profession. The reserve and discipline sinks in to their bodies and voices, and it’s there on the screen. It’s there in Collateral, when Vincent tells Max “if you attract attention, you’ll get people killed who didn’t need to die,” or in Max’s ability to know the fastest route from A to B even when he’s panicking. It’s there in The Insider, as Jeffrey Wigand talks about how Tylenol responded to a bad batch: “you had scientists in charge.” It’s there in The Last of the Mohicans, in the way Daniel Day-Lewis always keeps his eyes moving when he’s on watch, and even in the way Magua vows revenge–there’s no wild-eyed savagery about it, just the absolute focus and knowledge that he’s going to do it. (Magua remains one of my favorite Mann characters, because he’s one of the most uncompromised, and I was so damn happy to see Wes Studi show up in Heat.) It’s there in Thief, in the way, after breaking into a safe that looked impregnable, Frank just sits back and has a smoke. There are many more examples; feel free to add to the list in the comments.

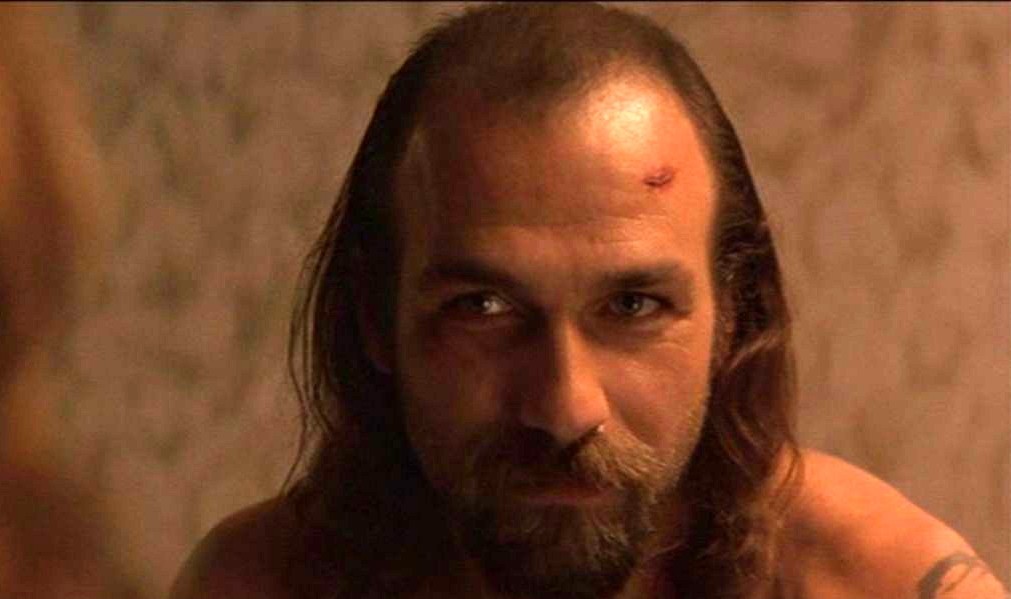

Heat features as a supporting and crucial character one of Mann’s most unforgettable creations, and one necessary for his universe: Waingro, the hired thief and unprofessional killer. Waingro isn’t merely unprofessional, he’s the antiprofessional, entirely a creature of hate and impulse. He’s signaled as such in his first moments on screen, in the staredown between him and Cherritto–you can see that every moment for Waingro he has the need to dominate everything around him. He kills entirely for the thrill of it, whether it’s a guard or a young hooker, and by letting this man into their world, McCauley’s crew sets in motion all the actions that will destroy them. In one character, Mann entirely dispenses with the notion of the romantic outlaw (Kurt Sutter’s Sons of Anarchy was a fascinating attempt to write an epic around this kind of character); to live outside a professional code isn’t heroic, it’s the truest villainy in Mann’s world. You could never say that Waingro is only doing a job. Kevin Gage, like all great Mann actors, embodies him down to the smallest physical action. When he says “the Grim Reaper’s visiting with you now,” the slightest widening of the eyes and leaning forward transforms him into one of the great horror-movie images in all cinema.

The code of professionals is all through in the coffee shop scene in Heat, the essence of Mann’s philosophy. Remember that this scene is the genesis of the film, and that it actually happened: a Chicago cop named Chuck Adamson ran into a professional thief he was after (named, interestingly, Neil McCauley) and invited him to have coffee and talk. Their conversation got Manned up into this scene, but the basics were there in reality. Every time I watch this scene, I see something new; this time I noticed how both de Niro and Pacino are always just on the verge of smiling at each other. (I also notice the beautiful, expressive Asian woman just behind de Niro, who fits right into 1995 Los Angeles.) The underlying theme of this scene is until death do us part; both characters declare who they are, and who they are, as professionals, is what they do. “I don’t know how to anything else.” “Neither do I.” “Tell you the truth, I don’t much want to.” “Neither do I.” (The dialogue is nearly as formal as a wedding ceremony, too.) The threats at the end are mechanical, but necessary, and neither reacts with any surprise; on this level, it’s only one professional who can understand another.

The code of professionals is all through in the coffee shop scene in Heat, the essence of Mann’s philosophy. Remember that this scene is the genesis of the film, and that it actually happened: a Chicago cop named Chuck Adamson ran into a professional thief he was after (named, interestingly, Neil McCauley) and invited him to have coffee and talk. Their conversation got Manned up into this scene, but the basics were there in reality. Every time I watch this scene, I see something new; this time I noticed how both de Niro and Pacino are always just on the verge of smiling at each other. (I also notice the beautiful, expressive Asian woman just behind de Niro, who fits right into 1995 Los Angeles.) The underlying theme of this scene is until death do us part; both characters declare who they are, and who they are, as professionals, is what they do. “I don’t know how to anything else.” “Neither do I.” “Tell you the truth, I don’t much want to.” “Neither do I.” (The dialogue is nearly as formal as a wedding ceremony, too.) The threats at the end are mechanical, but necessary, and neither reacts with any surprise; on this level, it’s only one professional who can understand another.

There’s a poetry to the language here that goes through all of Mann’s films; I can see not liking it, but it’s a unique voice. It’s a lot like Terrence Malick’s voice, and for the same reason: unlike most modern characters, Mann’s characters are hyperaware of who they are, and speak that awareness (often in diners). They have grown past the point of trying to charm or accommodate others. James Caan’s Frank in Thief is the origin point of this, but it’s there in all the characters, speaking the truth of themselves with the language they know. It really is poetry, if you consider compression the primary aspect of poetry, the poetic ability to load a few words with enormous meaning; “that’s the discipline” tells us everything we need to know about McCauley. Mann also shows us the poetry in professional language, the way people on the job communicate; like the truth of their selves, it’s forceful, simple, and compressed (“run Slick as an alias. You’ll get the phone book. Do it anyway.”)

Another part of what makes Mann’s characters so compelling is their maturity; everyone in his films looks to be at least in their 30s. (If you had to describe an anti-Mann film, it would probably be Superbad.) Mann’s characters aren’t finding themselves, they found themselves some time ago. (A fascinating near-exception to this is Collateral’s Max, who has found himself and become an excellent cab driver, but doesn’t realize it; it’s possibly that he’s so good at it that it’s blocking him from taking the next step.) That’s so beautifully realized in Heat, catching de Niro and Pacino in their 50s, old enough to have so much experience in their faces and bodies but still young enough to be active. (By the time of Righteous Kill, both of them looked like acting was interrupting their nap schedules.) You can also see it in Val Kilmer, in what is still his best performance; the matinee idol of Top Secret! and Real Genius starting to go to seed, looking like a character out of Raymond Chandler or Nathanael West. Mann’s characters have come to know and accept who they are, and there can be pain as well as glory in that.

Mann has little interest in the post-Shakespearan virtue of the “well-rounded character.” Mann’s characters are clichés, to an even greater extent than in most other authors. They’re not characters who are nearly cliché but miss by about 5% (as in Shawn Ryan’s work, and that 5% is what makes them interesting); they’re not characters who start as stereotypes and develop into something else (as Joss Whedon did in the Buffy and Angel series); they are straight-up stereotypes for the whole film. Mann’s characters work not in spite of their stereotypical nature, but because of it, because he has the discipline and thoroughness to imagine what these characters are like, how they will act, what their past was like, how they will dress, how they will speak. Mann’s films demonstrate what it’s like to live in this world as that ideal type, and in doing so he turns “cops into Cops, crooks into Crooks, and heroes into Heroes” in Scott Tobias’ words; he turns stereotypes into archetypes.

Mann has another specific strategy to make that work, and it goes to his respect for the profession of acting. Mann works with his actors to give his characters detailed backstories that never appear in the film, or just barely appear. In addition to training the actors in whatever actions they’ll be doing, this gives the performances a weight that you just don’t see anywhere else; Mann’s characters carry a history with them, even if we don’t know what it is. For example, I always felt that Crockett in Miami Vice had fucked up huge-time at some point in his career; there was a haunted aspect to Colin Farrell there I’ve never see before or since. Another good example comes from Ashley Judd’s character in Heat: Mann and Judd decided that she had worked as a hooker while Kilmer’s character was in prison and paid her way through community college. We don’t know that, but it comes through in her zero tolerance for his bullshit. It’s one of the things that allows us to imagine a past and future for Mann’s characters, and to see them as more real. Like his settings, the characters have the density of real things.

A key formative aspect to Mann’s criminals is the time they spent in prison. It not only gives them their particular set of skillz, but it also gives them a hard survival instinct and, more importantly, their necessity of being alone. Mann began his film career by studying prisons; he was an uncredited author for the film Straight Time (follow the chain of references: that was based on the novel No Beast So Fierce by Edward Bunker, based on his time in San Quentin and after. Bunker appeared as an actor in Reservoir Dogs and Mann and Jon Voight paid tribute to him in Heat by modeling the appearance of Voight’s character on him) and his first outing as a director was the prison-set The Jericho Mile. Mann’s knowledge of prisons comes out in little details like the napkin that de Niro wraps around a glass of water, and the major statements like the criminal’s credo that McCauley expresses so beautifully and archetypally in Heat: “remember what Jimmy McElwain used to say in the yard at Folsom–you want to be making moves on the street, have no attachments, allow nothing to be in your life that you cannot walk out on in thirty seconds flat if you spot the heat around the corner.”

That line lands because so much of Heat demonstrates its truth. Part of the story in Heat is the heist; the other part is the life of its characters with their families, and the impossibility of that. All the major relationships between men and women fall apart, and what’s clear by the structure of the plot is that they have to. I don’t feel any sense here that it’s heroic, there’s no sense of a Real Man Stands Alone; there’s only that sense as in classic drama that it’s necessary. It’s necessary because, as McCauley sez, if you want to pursue him, how will you have time to have any other life? (Great line from Nate the fixer, about Hanna: “he’s been married three times, what does that tell you, he likes staying home?”) It’s necessary because that heat is always around the corner, waiting, and you have to be ready to run at all times; you can see that in the first meeting of McCauley a and Eady (Amy Brenneman), when he mistakes a conversation for surveillance. (The Shield has a lot in common with Heat, and this is the strongest thematic point of contact, because The Shield uncovers one more truth to Jimmy McElwain’s credo: you have no attachments because you put them in danger, not just you.)

Mann has yet to write any female characters as iconic as his male characters, although Diane Venora comes damn close in Heat. (In Shield terms, Mann has never written a Mara.) They’re forceful, they’re definitely characters, but they’re not professionals and not who the films are about. That’s why the family scenes in his films can come off as clumsy, because it’s not where his real energy is, any more than Hanna’s. (Amy Brenneman, on reading the script for Heat, said she hated it–hated the characters, hated the violence. Mann told her that’s why she had to be Eady, because she was the only one who wasn’t in this world.) In Miami Vice and Blackhat, though, he’s been bringing women into the professional world and making them characters, and I hope he continues to do so.

Perhaps it’s Mann’s commitment to professionalism that makes him love actors so much. Mann gives room for actors to do their thing, things that don’t necessarily fit in with the movie, but make them feel warm and human. This has been especially true since Ali, really the most populated and overstuffed of Mann’s films, but those moments are in all of them, moments where actors just cut loose. (There’s also a wonderful touch in Heat, in the last hour–every major character gets a closing shot, a moment when the story has moved on from that character but Mann just holds the camera on the face. It’s unbearably poignant in the last shots of Ashley Judd and Val Kilmer.) Think of Bruce McGill’s speech in The Insider, or Javier Bardem (never so motherfuckin’ suave) narrating the story of Pedro Negro in Collateral. Most of all, watch Tone Lōc in Heat in one scene steal the movie, launder it, invest it in a Cayman Islands tax shelter, retire and live off the proceeds. I have a huge stupid grin on my face now because that’s my reaction every time I remember him saying “and that’s how I KNOW, that this cat’s got something goin’ dowwwwwwwn.” (It’s one of the moments where comedy goes beyond funny into pure joy.) It’s one of the great pleasures of watching movies to see actors do things like this; I suspect for Mann it’s a pleasure of making movies, too.

Among younger filmmakers, Christopher Nolan resembles Mann the most, something he explicitly acknowledged (and homaged) in The Dark Knight. (I’m pretty sure William Fichtner plays an alternate-universe Van Zandt in Nolan’s film; I’m just disappointed Henry Rollins couldn’t come along for the ride.) There’s the same sense of a code and of men doing their jobs in Nolan’s films; what makes him unique is that, unlike Mann, Nolan sets his films in a different reality. Mann grounds his film as much as he can in our world, but Nolan invents his own rules for a world, and that makes the code for a Nolan hero much more extreme than a Mann hero. (It also creates challenges for the actors that are far different than in a Mann film–as an actor, how do you appear to master a profession that doesn’t actually exist? In Inception, for example, Ellen Page, Dileep Rao, and especially Tom Hardy were well ahead of the rest of the cast in giving the correct professional feeling.) Among Nolan’s films, I find The Dark Knight to be the most successful, because it most clearly set up the challenge of the code; it’s a film about the struggle of Bruce Wayne to be Batman, the Ideal of Justice. (Of Nolan’s Batman trilogy, this one is the strongest drama, and The Dark Knight Rises is the best comic book.) The Prestige comes in a close second; it has the same relation to Nolan’s career that Heat does to Mann’s, or Zodiac does to David Fincher’s–it’s his most Nolanian film, the one where his themes are the clearest. It’s where we see that this kind of code is something you have to live at every moment in your life, and you have to be able to die for it too.

You can also get a good sense of Mann’s characters by comparing him to his near-contemporary Martin Scorsese. (The following derives from a conversation I had last year with the ever-insightful Chapman Baxter.) One can characterize the Mannly man in a single word as “professional”; for Scorsese’s characters, the single word would be “volatile.” Scorsese’s characters are explosive, impulsive, raw, in contrast to the reasoning of Mann’s characters. Scorsese’s characters have a moral dimension to them that Mann’s characters don’t, because with his strongest characters, their volatility comes from the distance between themselves and their ideals. (Charlie in Mean Streets, Jake LaMotta, even The Departed’s Billy Costigan are all examples of this, but I’ve argued that the truest version of this character is Jesus.) With Mann, the conflict lies between their actions and their code, but they don’t experience the very Catholic conflict between good and evil that Scorsese’s characters do.

The emphasis on professionalism and codes gives makes Mann’s films embody one of the most classical virtues: reason. It’s not a virtue that has much place in contemporary culture. The word “reason” usually has the words “cold” or “logical” near them, and it’s usually used in opposition to “feeling.” The nearest word to the classical meaning of reason would be “discipline,” meant in exactly the way McCauley means it in Heat. Reason doesn’t limit your feelings, it allows you to live and embody them. It’s the ability to plan and to foresee, to figure out “is this worth it?” to calculate, as the real Neil McCauley did and as so many Mann characters do, “risk versus reward.”

Mann has often been compared to Kubrick, and it’s an especially revealing comparison when it comes to reason; where Mann believes in reason, Kubrick pushes it to the point where it self-destructs. Beginning with The Killing, Kubrick’s films had a recurring theme of reason as a form of male madness; his films have male protagonists who continually overestimate how much they can plan and control the world as the world around them spins out of their control. You see this theme most clearly in Dr. Strangelove, but it’s there in all the films; for me, this theme works best in 2001, as it’s HAL who goes mad. Kubrick’s heroes see their reason fail, but they don’t know any other way to approach the world. Mann’s heroes do live by their reason and discipline, and they die by their lack of them.

The virtues in contemporary films are really those of nineteenth-century romanticism: self-sacrifice, commitment, love at first (or at most second) sight, heroic quests. There’s not a lot of risk-vs.-reward calculation there; it’s all about risking everything. Those are good enough virtues, but they have a tendency to get you killed pretty quickly, but of course that’s not a problem in a play or a film, since it’s all over in a few hours anyway. Mann’s commitment to reason helps ground his characters in our reality, as much as his commitment to getting the details of their actions right. That Mann’s characters don’t hold self-sacrifice as a virtue, that they commit to acting professionally, means that they can go on with their lives and their actions.

Reason hasn’t been doing too well in contemporary critical discourse, either. It’s hard to say what the virtues are there, because the world isn’t a tightly structured as a Michael Mann film. Probably “identity” or “voice” is up there, though, as a critical virtue; the “place” we criticize from, and the identity of the writer, has come to matter more and more. Without question, this virtue and contemporary discourse has brought in a lot of voices that we’ve never heard before, probably the greatest accomplishment of our time, but identity is, almost by definition, not a universal virtue. Plato, Roger Bacon, and Immanuel Kant thought of reason, the discipline and reflection that Mann’s characters live so well, as a universal virtue; indeed, it was because it was accessible to all that they thought of it as a virtue. For them, it was the virtue that made all other virtues possible, because it allowed one to exercise those virtues and live them, not just believe them. For all the new voices that have joined the discourse in my lifetime, I’ve never been successfully convinced that those philosophers were wrong. I suspect this kind of reason and discipline will always be with us, and so will Mann’s films.