The chair has four legs… Now, an animal has a one track mind, For instance, the animal is coming after you with the idea of tearing your head off… You put the chair up, and all of a sudden, he has four points of interest. He loses his original train of thought because this agitates him. He can’t comprehend those four points of interest, so what he does he attacks the chair. He takes his wrath out on the chair. His mind now had been completely distracted from his original thought: “Eat the man in the white pants.

–Dave Hoover

Let’s begin by considering the mechanics of the metaphor. Shakespeare’s Romeo doesn’t say “Juliet is radiant,” he says “Juliet is the sun,” and readers extract the relevant qualities from “sun” (“radiance”) that might apply to Juliet, and discard the irrelevant (“giant molecular furnace”). The word “radiance” may be unspoken, but it hangs in that gap in between, waiting for us to complete it, making us partners in the creation of meaning.

So when I say that Errol Morris’ Fast, Cheap & Out of Control is his most “poetic” film, I don’t mean that it’s necessarily his prettiest or his most florid, or whatever else the word “poetic” might imply about its visual presentation. I mean that the movie’s “meaning” exists almost entirely in this in-between space in which we are invited to participate, a sustained experiment in metaphor that goes deeper than any of his other films, but whose deepest meanings are unspoken until and unless you give yourself over to the process. (As much as this is an “Errol Morris film” in its focus and attitudes, this is his most pointedly edited film, and so a great deal of its power comes from the work of editors Shondra Burke and the late Karen Schmeer.)

The surface content of the documentary is relatively straightforward: Morris corralled four disparate area experts to discuss their life, their work, and their philosophy. Rodney Brooks is a robotics professor at M.I.T. obsessed with notions of biological systems and determination. Dave Hoover is a lion tamer who reminisces about the heyday of his profession, especially his childhood idol Clyde Beatty. Ray Mendez is a naturalist whose expertise in insects made him the perfect person to introduce America to the insect-like social world of naked mole rats. And George Mendonça is a topiary artist nearing the end of his life, wondering who will take care of his creations when he’s gone.

Individually, each of these stories is interesting in its own way: a deep dive into subject-area expertise by four passionate professionals, each one with just a touch of the quirkiness that so often draws Morris to human subjects. But the film achieves its power–its poetry–from that ways that the four interviews seem to exist in dialogue with one another, with ideas drifting between them, sometimes echoing, sometimes polemicizing, but always allowing us to fill in the gaps. There are natural overlaps even before the editors start working their magic. Hoover and Mendez are talking about animals. Mendez and Brooks are talking about complex systems. Mendonça and Hoover are talking about art. There are also natural frictions, especially related to generational issues. Mendez and Brooks are young and excited about the possibilities of new knowledge; Mendonça and Hoover are melancholy about the eventual disappearance of their work and way of life.

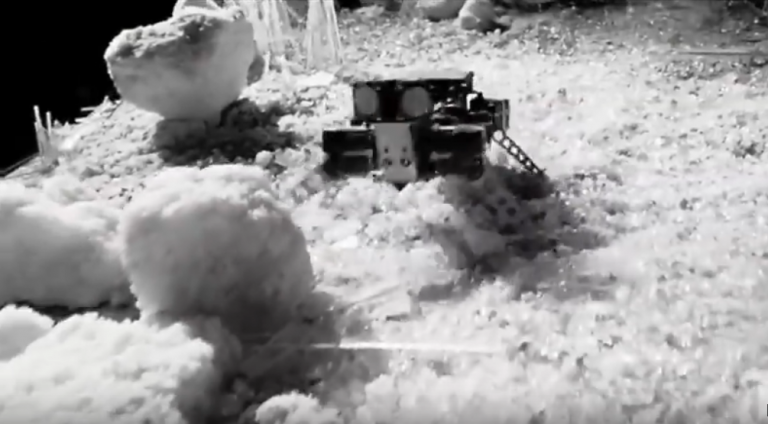

It’s Brooks’ story gives Morris the title, also the title of his 1989 paper (pdf) arguing that the popular vision of interplanetary exploration is inefficient in all senses of the word. Instead of trying to build spaceships or complex rovers, we should be sending out tiny rovers, metal “gnats,” and other micro-machines with more specialized functions that would lower both the expense and the likelihood of failure. His argument is that systems are more efficient than individual machines, and programming a million tiny robots with very specific functions would allow us “to invade the entire solar system.”

Again, a fascinating enough topic on its own, and behind Brooks’ eyes we can see the twinkle of someone who might be enjoying the invasion metaphor a bit too much. But look at how Morris turns his vision of robot mini-conquistadors into a larger observation about, well… finish the metaphors for yourself:

BROOKS: It stops where it is, and it turns up this little corner reflector to the sky. And wherever these robots are with the little corner reflectors, you see a little sparkle. So now all the robots have accumulated where the particular chemical we’re looking for is, and you get this automatic map.

MENDEZ: The soldiers have routines and songs that are used when they’re going out to protect the nest. One individual being attacked by a snake, another individual is walling that individual off. Although the snake got one, it wouldn’t be able to attack the nest. The expendability of the individual. In ideal situations, you would say, well, they would all go and try and save the individual, right? Attack the snake. For all the workers, it safer just to say: “Well, you know, ‘X’ died, and we’ll seal him off.” The Queen will have another 22 babies, or 14 babies, or 7 babies.

HOOVER: You have to experience an injury. You have to experience chaos. My fear is misjudging an animal, being at the wrong place at the wrong time. Misjudging conditions outside the cage. A storm, electrical storm. Now, thunder doesn’t bother them, an electrical storm does bother them. A lion or a tiger can run 100 yards in 3 and a half seconds, and I’m in a forty-foot cage. They can nail you before you say: “Oops…”

MENDONÇA: It’s a touchy situation. You’re fighting the elements to try and get them to grow where you want them to grow, get them to do what you want them to do. If it’s not one thing, it’s the other… And then, of course, the different insects that come in… They’ll eat anything. If they haven’t got what they like they’ll take the next best thing. It’s a constant battle all the time.

On the surface, four experts talking about four different things, but the temptation to draw meaning from their juxtapositions, to tease out what lies in that in-between space, is where Fast, Cheap really soars. Because they are juxtaposed so pointedly, the temptation is to read one as a metaphor for another (i.e. what Mendez is saying about mole rats works as a metaphor for what Brooks is saying about robot herds), but because none of the terms are “anchored” (like “Juliet” in “Juliet is the sun”), the metaphor works both ways: each is effectively saying something that can be interpreted and applied to the other. With no anchor, and nothing but “in-between” meaning driving the development of ideas, the film carries us afloat into a steady stream of abstractions, making it hard to say what exactly the film is about other than the experience of free intellectual play and the meaning we derive from it.

Morris even ups the ante by giving us a third term in these juxtapositions: the visuals (this is a film, after all). Sometimes Brooks will be discussing robots and Morris will show us mole rats. Sometimes Mendonça will be discussing his topiary “animals” and Morris will show us circus lions. A few visual cues become leitmotifs: the carnival, with its clowns and trained animals, seems to reflect in entirely different ways depending on which of the four monologues it’s juxtaposed against. Ditto an old Clive Beatty B-movie, with its flying monkeys and hidden jungle kingdoms. Now the film’s meanings pull us not between two or more monologic ideas, but also between an entire range of visual cues, and possibilities for our free intellectual play expand into yet another dimension.

If anyone can explain the movie’s intangible magic, it’s A.O. Scott, yet look at how Scott struggles (on purpose) to put it precisely into words:

Much of Errol Morris’ career, especially since the 2000s, has been focused with more precision on issues of epistemology: how do we know what we know? How can we be sure? It’s a thread that’s been in his work since at least The Thin Blue Line, but has increasingly dominated his interests since The Fog of War (including all three of his books). He’s one of the great, most inquisitive figures in modern filmmaking, but he’d never before and has never since made a movie of such intangible magic as Fast, Cheap.

The autumnal note struck by both Hoover and Mendonça is what has stuck with me the longest all these years: as exhilarating as the movie can be, it’s also cut through with a deep melancholy. Death, the passage of time, hangs over the late sections of the film, most memorably crystallized in the image of Mendonça walking among his creations in the nighttime rain, knowing that he won’t likely live to see some of them full-grown. (Scott Tobias over The New Cult Canon called the film an “ultimately life-affirming” meditation on death.) Death also followed the production: Caleb Sampson, the young composer who gave Fast, Cheap its score–a more flexible, more playful version of Phillip Glass that builds tension while also pirouetting between different genres–ended his life shortly after the film was completed.

As for the four subjects in front of the camera: Rodney Brooks and Ray Mendez are still out there doing their things. Dave Hoover passed away at in 2006 the age of 75. George Mendonça passed in 2011 at the age of 101, the very day after his wife.