I’ve actually been meaning to catch up with Shanghai Surprise for some time: growing up in the 1980s, of course I was familiar with the Indiana Jones franchise and many of the other pulp-revival movies and television series that followed in its wake. Eventually, I started digging into the original movies and books from the 1930s that had inspired Spielberg and Lucas in the first place: this past summer, for example, I plowed through ten serials, in part as a way of getting in touch with this source material. In a way, the adventure narratives of the 1930s have been for me what Madonna has been for Julius: always present, a lens through which I have been able to look at many different subjects. (You can read Julius’ take on the film here.)

But I hadn’t seen Shanghai Surprise: as you will see, I had some misconceptions about it, but I’m mostly surprised I didn’t see it because I was so voracious in tracking down and watching Raiders of the Lost Ark knock-offs as a kid, even grade-Z stuff like Treasure of the Four Crowns (in Super-Vision 3-D!) or The Perils of Gwendoline in the Land of the Yik Yak (the cause of a mildly awkward incident in college when I recommended it for a co-ed movie-watching night, somehow forgetting that the last third of the movie centers on half-naked Amazons in bondage gear wrestling to the death). Mostly, Shanghai Surprise seems like the kind of movie that would have played on the USA Network on Saturday afternoons for years, if it weren’t for the fact that everyone involved would probably rather forget it existed.

As an example of the “Americans in the Orient” subgenre, Shangai Surprise hits most of the expected beats and (considering its limited budget) makes the most of location shooting that turns Hong Kong into pre-war Shanghai. Few clichés of exotic Asia are left unused: rickshaw chases and opium dens, sadistic torture perpetrated by an inscrutable mastermind, and a high-class concubine with pretensions of Imperial lineage. The only thing missing is a martial arts set-piece, and there isn’t a ninja in sight, but between this and the far superior, self-aware Big Trouble in Little China, released the same year, all the stereotypes are covered.

Shanghai Surprise gets off to a promising start: it’s 1937 and occupying Japanese troops are filling the city. Two westerners are preparing to leave, one cool and one anxious: “opium king” Walter Faraday (Paul Freeman, Raiders of the Lost Ark’s Belloq himself) is crating up one last score, a thousand pounds of high-grade opium, while corpulent journalist Willie Tuttle (Richard Griffiths, aka Harry Potter’s Uncle Vernon) frets that they won’t get out before the Japanese close the city. Soon enough, Faraday’s servant Wu (George She) betrays him, stealing the opium, and Faraday is cornered by a Chinese officer, Mei Gan (Kay Tong Lim), with whom it’s obvious he has some history. Rifling through Faraday’s money belt, Mei Gan triggers an explosive trap (the “Shanghai surprise” of the title) that removes his hands, shown in gory detail. The pair make a break for it, but Faraday is gunned down by Mei Gan’s men, leaving only Tuttle to tell the tale of the soon-to-be-legendary lost opium shipment.

If the film had maintained the excitement generated in the prologue, it would probably be fondly remembered as a cheesy throwback to the adventure movies of the 1930s and ‘40s, part of the post-Raiders vogue that was winding down by 1986. The set-up recalls the beginning of The Perils of Pauline: the 1933 Universal serial (not the more famous 1914 silent) begins with a British scientist refusing to leave China in the face of ongoing revolution until he has recovered a treasure from a nearby temple, despite the pleadings of his daughter. (There is even a strong resemblance between Pauline star Evalyn Knapp and the star of Shanghai Surprise, and I think I even saw some honest-to-God undercranking during a fight scene in Shanghai Surprise, an old trick to make the action punchier and more exciting.)

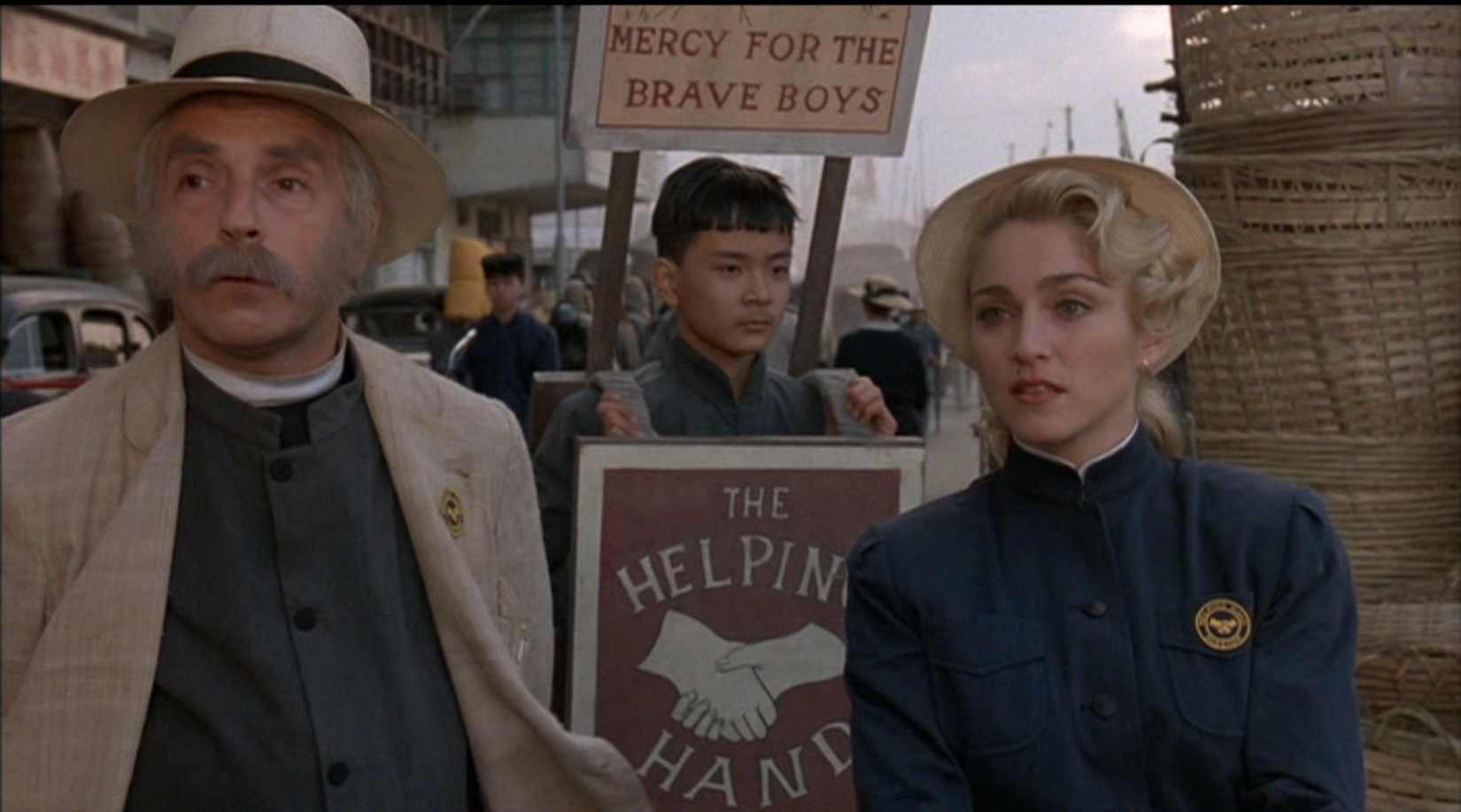

After flashing forward a year and shifting its focus to stars Madonna and Sean Penn, however, the film lurches unevenly, burdened by awkward dialogue, improbable plot twists, and most fatally a lack of chemistry between its two leads. Madonna plays Miss Tatlock, an uptight missionary seeking the missing opium to convert into morphine for the war effort; Penn is Glendon Wasey, the cynical, self-interested scoundrel she ropes in, who only wants to get his shipment of painted neckties back to the States. Shanghai Surprise aims for a Romancing the Stone-like balance of adventure, comedy, and romance, but succeeds only intermittently.

There is a natural expectation that over the course of the story Wasey will find some goodness in his mercenary heart and Miss Tatlock will loosen up and learn to bend the rules to get what she wants. But neither character is quite as good or bad as they seem. When Wasey is first seen, he’s drunk, shirtless, unshaven, and arguing with a boatman. His drinking, swearing, and leering establish him as a bad boy in the mold of Han Solo or Romancing the Stone’s Jack Colton. But while it’s clear Miss Tatlock disapproves of his uncouth manner, there’s no suggestion that he’s involved in anything as overtly criminal as smuggling spices or exotic birds. He certainly isn’t the type to shoot first when cornered by a bounty hunter: he doesn’t even carry a gun. Even the suggestion that he might double-cross the missionaries is half-hearted: his primary assets are his street-smarts and fluency in Chinese; his primary goal is passage to America and escape from the various crazies pulling him into their schemes.

For her part, Miss Tatlock hints at a more complicated past than she lets on—she smokes, she knows how to pick a lock, and she alludes to skipping curfews at a prestigious girls’ school—so when she inevitably falls for Wasey it doesn’t feel so much like opposites attracting as the discovery that they’re not so different (the way it happens defies belief, but more on that momentarily). Miss Tatlock is so inconsistent in her behavior and mannerisms, however, that even extending that much credit to her character development feels like a stretch. Miss Tatlock bears comparison to Jean Simmons’ Sarah Brown in Guys and Dolls, a similarly repressed character who opens herself up to new experiences and love, but whereas Simmons makes this transformation feel organic, Madonna flounders.

It’s a common perception that Madonna is a terrible actress, a view Shanghai Surprise does nothing to dispel. (To be fair, Penn doesn’t come out too well, either: famously involved with Madonna at the time of production, he reportedly didn’t want to participate, and his lack of commitment shows in every frame.) However, the problem (at least with this role) isn’t one of credibility, it’s one of consistency: Madonna makes small moments work, but they contradict one another and don’t add up to a believable character, and she is out of her depth trying to make the script’s wild swings in tone work.

In one long sequence, Wasey has a rendezvous with the subtly named China Doll (Sonserai Lee), a courtesan with inside knowledge of both the opium and an even greater treasure; the scenes in which she alternately tests and pleasures Wasey play like a parody of the similar East-treats-West scenes in You Only Live Twice. Shanghai Surprise was based on Tony Kenrick’s 1978 novel Faraday’s Flowers (which I haven’t read), and perhaps the scene plays better in the book: it certainly feels like something from a steamy potboiler. In the film, Sean Penn doesn’t have Sean Connery’s aura of sexual dominance, and mostly looks embarrassed to be there. His ironic smirk is the only saving grace of the sequence: he can’t believe this shit either.

Even worse is the next scene, in which Miss Tatlock undresses and forces herself on Wasey in order to “obligate” him to continue helping the mission. On paper the scene is screwball comedy, as Wasey refuses and finally relents (“I’m obligated! I’m obligated!”); in reality it’s a cringe-inducing low point of the film, and an example of how a weak script sabotages Madonna’s efforts. Maybe Miss Tatlock is desperate and frustrated enough to try anything to keep Wasey hunting for the opium; maybe she’s secretly fallen in love with him and his liaison with China Doll has made her jealous; or maybe she’s reverted to the hinted-at wildness of her younger self. There are suggestions of each of those motivations, but not enough support for any one of them to make the scene believable. Even after giving in, Wasey looks pained and uncomfortable: I knew how he felt.

I might as well mention another demerit against the film: its music. Before I watched this, I was under the mistaken impression that it was inspired by the Shanghai sequence in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, with Madonna playing a role comparable to Kate Capshaw’s nightclub singer Willie Scott. If only: Shanghai Surprise isn’t a musical, and Madonna doesn’t sing in it; the music is provided by George Harrison (whose Handmade Films produced) and longtime Handmade collaborator Michael Kamen. I used to like Harrison, but the best songs on the soundtrack merely rise to “forgettable.” The worst is the song that accompanies Wasey and China Doll’s lovemaking, with the list of China Doll’s exotic-sounding sexual specialties turned directly into song lyrics. Ugh. The instrumental parts of the score, provided by Kamen, combine boilerplate chinoiserie (up to and including “Chopsticks”) with cheap-sounding mid-‘80s synthesizers. The only musical moments that come alive are a few Harrison-penned jazz numbers played by a real band, drawing on an interest that occasionally surfaced in Harrison’s solo albums (he appears in a cameo as the guitarist of the Zig-Zag Club’s band). An entire soundtrack in that vein would have gone a long way toward redeeming the project.

There are some bright spots, however, much of it in the margins, with seasoned character actors adding color to the proceedings. In addition to those already mentioned, familiar faces include Big Trouble in Little China’s Victor Wong (sadly wasted in a silly bit part that could be cut without affecting the plot); Philip Sayer as an eavesdropping meddler; Clyde Kusatsu as Joe Go, a slangy, baseball-obsessed black marketeer; and Professor Toru Tanaka as Go’s hulking bodyguard. Each of these characters have an angle and an interest in the treasure, and the finale is a flurry of double- and triple-crosses as the treasure is discovered and everybody scrambles for it, finally revealing their true agendas. Above them all, Kay Tong Lim is menacing and aloof as Mei Gan, who turns up with a creepy pair of prosthetic hands that makes him seem very much like someone from a James Bond movie, but this time in a good way.

There’s no question that Shanghai Surprise deserves its poor reputation; it’s not an unjustly forgotten gem by any means. But there is a sturdy foundation to the story, and enough good parts that it’s tempting to consider what might have been. In the hands of a director like, say, George Roy Hill, instead of television veteran Jim Goddard, and with a better (or more pliable) leading lady, Shanghai Surprise could have been a classic—minor, to be sure, but a classic. Even in the form in which we got it, while I would never says it’s a great (or even good) film, it has its charms if you’re willing to overlook a few problems.

Okay, a lot of problems.