One of the most well known serial films ever, The Perils of Pauline is an interesting look into early film. Released in 1914, at a time when the movie going audience was primarily women, Perils catered to this audience by reflecting the then growing social construct of the New Woman. Co-produced by newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, the series sought to replicate the success of Whatever Happened to Mary, a print serial turned film series that debuted two years prior. They were assisted by the French film company Pathé, who was trying to gain a foothold in America.1 The serial starred Pearl White, and was directed by frequent Pathé collaborator Louis J. Gasnier with the help of Donald MacKenzie. It was written by playwright Charles W. Goddard and George B. Seitz, the latter would go on to a career almost exclusively writing and directing in this genre. It ran for 20 episodes, an unusually long length for a serial.Like its contemporary serial-queen melodramas, Pauline attracted a large female audience that was drawn to its apparently transgressive narrative about an independent woman seeking adventure.2 A note before we go further: though the American version of the serial is lost, a 9-episode European cut (which retains the opening and closing episodes at least) survives. This is the version this paper was written from.

One of the most well known serial films ever, The Perils of Pauline is an interesting look into early film. Released in 1914, at a time when the movie going audience was primarily women, Perils catered to this audience by reflecting the then growing social construct of the New Woman. Co-produced by newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, the series sought to replicate the success of Whatever Happened to Mary, a print serial turned film series that debuted two years prior. They were assisted by the French film company Pathé, who was trying to gain a foothold in America.1 The serial starred Pearl White, and was directed by frequent Pathé collaborator Louis J. Gasnier with the help of Donald MacKenzie. It was written by playwright Charles W. Goddard and George B. Seitz, the latter would go on to a career almost exclusively writing and directing in this genre. It ran for 20 episodes, an unusually long length for a serial.Like its contemporary serial-queen melodramas, Pauline attracted a large female audience that was drawn to its apparently transgressive narrative about an independent woman seeking adventure.2 A note before we go further: though the American version of the serial is lost, a 9-episode European cut (which retains the opening and closing episodes at least) survives. This is the version this paper was written from.

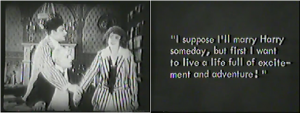

The opening title cards reveal the history of the protagonist Pauline, who was orphaned at a young age and taken in by the kindly Mr. Marvin. Over the course of the first episode, we learn that with Mr. Marvin’s passing, half of his large fortune will go to his son Harry while the other half will go to Pauline, but only after she is married. If she dies before marriage, then her cut of the fortune will go to Mr. Marvin’s secretary Raymond Owen (known as Koerner in the surviving European version). Harry wishes to marry Pauline, but she refuses, wanting to live a life of independence and adventure. Eventually they compromise, Pauline has one year of adventure and at the end of that year she will wed Harry.

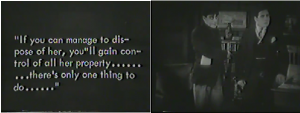

Prompted by his evil assistant, Koerner realizes that if he sabotages one of Pauline’s adventures that leads to her death, then he will legally inherit the fortune.

And so a formula is established for the series. Pauline decides to perform some dangerous task, such as ride in a balloon, drive a racecar, or pilot a boat. Koerner sabotages the device leaving Pauline, and sometimes Harry, in danger. Then, Pauline escapes the danger somehow, frequently with the help of Harry.

As an example, let’s look at the remainder of the first episode in the European cut, “Trial By Fire”. After the set up of the plot, Koerner suggests Pauline’s first adventure, having her picture taken in a hot air balloon.

While she is in the basket, Koerner’s assistant causes a commotion with a horse, causing the basket to start flying away. Pauline resourcefully drops an anchor from her basket, and climbs down the rope.

She lands on a cliff side, and then Harry comes down to meet her. Harry then comes up with an idea to climb up and deflate the balloon, allowing them to retrieve the rope used to climb to the cliff to climb off the cliff.

He is successful, but as they are walking away, Pauline is kidnapped by Koerner’s assistant, who ties her up and puts her in a building that he sets on fire. Harry then races to rescue her, and in the end succeeds. After that, they return to their home, and as Pauline and Harry celebrate, Koerner plots his next scheme in the background.3 Unlike our common conception of serials, the episodes of Pauline were all standalone. Only the first episode set up the plot, and the last episode concluded it, meaning that any other episode could take place in any order, hence why the European version is allowed to be so radically altered. For example, the balloon and fire section of the above episode took up episode six in the American print, while episode on had a different “peril” attached to the introduction. This pattern of story makes it easy to break down Pauline and show the kinds of gender dynamics that were present underneath its surface. 4

One likely explanation for the enormous popularity of Pauline and other like serials was the increased popularity of the New Woman. The New Woman was a cultural construct meant to embody women who were finding more and more independence thanks to the rise of modernity, and the serial-queen melodramas were one of the few pieces of culture that put them front and center.5 A big part of the allure of the serial-queen melodrama was a woman interacting with spheres usually controlled by men. Women took on the roles of spies, pilots, drivers, and other hero roles. They were always bachelorettes, and as such displayed a degree of autonomy. These heroines frequently were forced into life or death situations and had to rely on physical strength and/or cunning to survive. The use of these “male” qualities was attractive to the potential female viewers, who saw the films as an empowering fantasy.6 In Pauline we see examples of this in every peril the title character comes up against. She fights pirates, escapes from a leaking boat, and performs other escapades that require feats of strength and agility at the time only associated with male heroes. The specific example from the episode I examined, “Trial by Fire”, is the sequence where Pauline escapes from a runaway hot air balloon. As the balloon travels higher and higher, Pauline throws an anchor over the side, anchoring the balloon to the cliff side. She then climbs down the rope, landing her on solid ground.7 The two feats Pauline accomplishes, her intelligence that let her come up with the plan, and the physical strength needed to execute it, mark her as having these masculine traits. By bucking the stereotype of women that are weak and dependent on men, Pauline served as a role model for her female audience that was just starting to find their own independence.

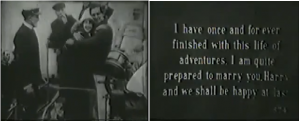

Though the serials were celebrated by their female audience for showcasing female independence and athleticism, they did not deliver an entirely revolutionary message. Indeed, the serial-queen melodramas, and Pauline in particular, still ultimately reinforced society’s gender norms. For example, though Pauline deserves credit for showing independence by taking part in activities deemed too dangerous for her, the only reason she is put into danger is because of her independence. Every sabotage by Koerner is tied to some masculine activity Pauline wants to do. Though Pauline shows off feats of body and mind escaping from danger, they are always reactionary to what is surrounding her. The heroine is clueless about Koerner’s treachery throughout most of the serial, and even his death in the end is not directly by her hand. Also, even Pauline cannot escape every trap. As mentioned above, she needs Harry to come up with the plan to get them off the cliff. This is a common pattern in episodes of the serial, while Pauline can get out of some traps, she also needs to rely on Harry’s ability to rescue her. The only place truly safe for Pauline is her home, which she starts and ends most episodes in. The house is thereby constructed as a safe place, one where Pauline is free from danger, and in the end is implied to stay there. 8 Pauline’s victimization is just as important as her heroism. Representing what Ben Singer refers to as “the graphic spectacle of female distress,” the serial brings up danger to Pauline in order to emotionally affect their audience just as much as the action.9 This is most evident in the scene where Pauline is trapped in the burning building. She is bound and helpless, unable to save herself until Harry comes to her rescue. Her victimization is just as exploited as her heroism, while Harry is only depicted as a hero. Despite any overtures towards equality, this inevitably puts Pauline on a lower level than Harry, since he never needs rescuing and is never victimized. Her temporary independence is an illusion, and let us not forget that it is still temporary. The one year time limit Pauline puts on her adventures in the first serial emphasizes the fact that there is a time limit to her autonomy. Marriage is inevitable for Pauline, and the serial gives the impression that that is the way it should be for all women.

The choice between love and ambition is central to not just Pauline, but other serial-queen melodramas too. Perils of Pauline ends with her marriage, and as such no sequels were made. Many serials either end with a marriage or have a sequel focusing on the marriage of their titular character. For example, What Happened to Mary was followed by Who Will Marry Mary? 10 So while Pauline and other serial-queen melodramas appear to tout equality on the surface, they still conform to gender norms.

The actress behind the serial, Pearl White, actively tried to reject the subconscious message of the work she starred in. White catered a fanbase that was engaged by her athleticism and other transgressive aspects of her personality. She is quoted as “liking beefsteak and aviation”11 and often performed feats that paralleled her screen counterpart, only this time without the sabotage. It is clear she served as an inspiration to many, as one contemporary article reports on two little girls who traveled from Connecticut to New York to try to see her.12 White was easy going in interviews and gave off a palpable impression that she loved her work. Another point of interest for fans, was how the actress performed her own stunts, even when they put her life in danger.13 Pearl wanted to prove that unlike the character she played, love and ambition could co-exist. Yet the actress was the subject of two divorces, one occurring near the start of her career in 1914, and the other at the height in 1921, the latter after only one year of marriage. She eventually gave up pursuing marriage and insisted on only valuing “companionship.” There are other examples of actresses who successfully married and continued with successful careers, which points out the hypocrisy inherent in their films. Many of these actresses were very outspoken too, though they failed to truly enact any social change.14 Mostly because the personal lives of these actresses were seldom reported on, indeed one of the few articles on Pearl White in the New York Times was a very brief notice about her second divorce.15 While actresses had a large part in shaping the thrill and popularity in the serial-queen melodramas, and certainly served as an inspiration to their fans, they were unable to refute the norms that their work reinforced.

There is no way of knowing whether writers like Goddard and Seitz intentionally wanted to undercut the independence of their heroines in order to enforce the current gender order, or if they were merely oblivious to the implications they were writing. I would lean towards the latter. Regardless, The Perils of Pauline paints a clear picture of using feminism as a selling point and a draw for audiences without fully committing to the values it represents. Pauline is an early case of a genre that thrived on false feminism, though given the inspiration they provided to women everywhere it is hard to call this a bad thing. Ultimately, I feel as if Pauline is neither a positive or negative cultural force. Every point of social progress made is undone by a conformist underpinning and vice versa. Instead, it is just a representative of its time, a sign of growing social change rather than an agent of it.

1 Raymond William Stedman, The Serials: Suspense and Drama by Installment (Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1977), 11.

2Shelley Stamp, “Serial Heroines, Stars and Their Fans” in The Silent Cinema Reader (New York: Routledge, 2004), 210-212.

3 The Perils of Pauline, directed by Louis J. Gasnier (1914; Phoenix, AZ: Grapevine Video, 2006), DVD.

4 Stamp, “Serial Heroines,” 214-215.

5 Ben Singer, “The Serial Queen Melodrama” in Melodrama and Modernity, (New York: Colombia University Press, 2001), 221.

6 Singer, “Serial Queen,” 223-226.

7 The Perils of Pauline.

8 Ibid.

9 Singer, “Serial Queen,” 254.

10 Stamp, “Serial Heroines,” 212-214.

11 Ibid, 218.

12 “Girls Flee Here to See Pearl White,” New York Times, (New York, NY), Sep. 01, 1922.

13 Stedman, The Serials, 12, 45.

14 Stamp, “Serial Heroines,” 220-222.

15 “Pearl White Gets Divorce,” New York Times, (New York, NY), Jul. 21, 1921.