“God Only Knows” is one of, if not the most critically analyzed piece of pop music ever written. In addition to its defenders within the industry (The Beatles famously spent all night spinning the record, trying to understand how Brian Wilson accomplished what he did), it’s also drawn the attention of academics and pop culture aficionados alike, a piece that sounds like a pleasant, if slightly melancholy piece of pop yearning built on a radical (for its genre) set of building-blocks. I’m going to try to explain, in the most non-expert way possible, some of ways that Wilson accomplishes so much strange ambiguity in “God Only Knows,” strange enough that it’s even left professional musicologists scratching their heads.

By its nature, Western pop music is (and this is an observation, not a criticism) fairly straightforward and fairly easy to understand: it uses a conventional set of structures, harmonies, and harmonic “movements” to fulfill a certain set of functions: verses and chorus, tension and release, a tonal “center” that everything else can gravitate around, etc.

Brian Wilson is interested in none of these things and dumps them all right outside the window. “God Only Knows” is a frustratingly ambiguous song on a technical level that somehow, miraculously, sounds effortless and even slight on a superficial level. You would never think, listening to its gentle pulse, that people can’t even agree on what key the damned thing is supposed to be in (Wilson himself has hinted at E major, as have most analysts, but there’s good reason to analyze it in A major as well; and even D major has its partisans.) How can such a straightforward-sounding song have so much discord under the hood?

First, let’s talk about chords. Chords are literally just stacks of notes, the most basic building blocks of Western harmonies. We have different types of chords (major, minor, diminished, etc.) that we name by referring to its “root”, or the lowest note in what we call its “root position” (in English: it’s “lowest” note in what we might call its resting position: think of a root like someone’s foot, and if they’re standing up straight, it’s on the floor). So, for example, a chord made up of the notes C, E, and G is what we call a C-major chord. It has a C root, a third above that (E), and a fifth above that (G). Other types of chords work the same way: F, A flat, C is called a F-minor chord; E, G sharp, B, D is called an E-major dominant seventh chord; B, D, F, A flat is a B-diminished seventh, etc. The first letter in each cluster is the one that gives its “name” to the rest, regardless of what kind of chord it is.

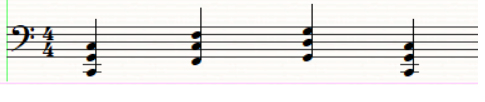

This is really key for pop music, and especially rock, which uses a lot of “power chords” (the root + the fifth + the root again up top, in this case: C, G, C). The most basic progression in Western popular music looks something like this:

You can see three different chords here, all of them in root position: the first is a C chord, the second an F chord, the third a G chord, and the last comes back home to C, each of them named for the “root” (or the “foot” in our metaphor).

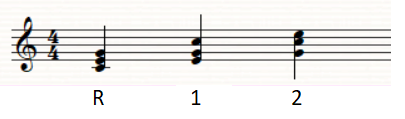

Ah, but people don’t have to stand up straight: they can tumble and do handstands or whatever. So if my notes are ordered E, G, and C instead, it’s still a C-major chord, just “inverted” (the foot’s way up in the air instead of on the ground). Here, for example, are the root position and two possible inversions of a basic C-major triad:

Music theory calls these first and second inversions, pop music calls them “slash” chords: here you have C, C/E, and C/G (the note after the slash is the one on the bottom). Just like a person doing a handstand, inversions are much less “stable” than their root-position versions: they feel like they can tumble over any minute. For that reason, though inversions aren’t super-rare in pop music (even power chords can be inverted), they’re not super-common either. The stability of the root position is what gives most pop music its clear sense of “home,” its clarity, its satisfaction.

One of the most basic tricks that drives the lush ambiguity of “God Only Knows” is how many of its chords are inverted, so that sense of “home,” that clarity, is harder to pin down. There’s a simple logic behind what Wilson does, though. If you look back up at the power chords example, you notice that progressions of chords in root position tend to jump around a lot: this works fine if they’re merely accompaniments, but they’re not particularly singable on their own. Wilson, who’s coming out of a barbershop-quartet tradition of writing melodies for the bass, as well, needs a bass line that sings, that works coherently in isolation. Writing for the bass line was one of his major innovations as a pop songwriter.

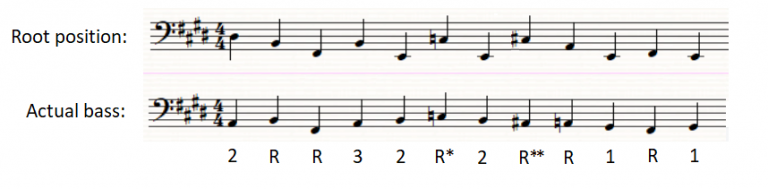

Check out the two examples below. The first is what the bass line of “God Only Knows” would look like if every chord were in root position. The second is the actual bass line of the song.

You may notice is that the top example jumps around a lot, where the bottom example, after the third note, only slides to the nearest note below or above: it’s a smoothly slithering line that one could plausibly sing along with. (I explain the asterisks in the Notes section at the end). The numbers below tell us which inversion each chord is in, and you’ll notice that a full half the chords aren’t in root position. Most of the song is doing handstands and tumbles, so to speak. In fact, the E-major chord (our ostensible home key) never appears in root position: the one chord we’re supposed to be drawn to, our tonal “center,” never provides the stability we’ve come to expect in pop music. How can you have a home key that never actually goes home?

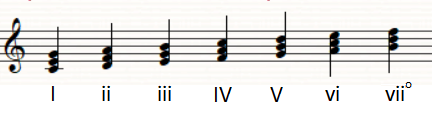

It’s far weirder than that, though. Each “key”, or tonal center, has a certain set of chords that appear “naturally” within what we might call the same “family”, and the members of that family have defined relationships. In the power-chord example above, the G and F chords belong to the family of C, and they represent what we call the subdominant (IV) and dominant (V) of C. Most pop music is content to stay within the same family, or to move to a nearby family through a process called “modulation.” Here, for example, are the basic chords that make up the natural “family” of C major, and jumping around between these harmonies would give us the overall “sense” that we’re in the family of C-major even if we haven’t stated it outright:

From the very beginning, “God Only Knows” makes it hard to figure out which family we’re actually in. The opening instrumental riff seems to promise an E-major home key, so let’s run with that for the moment. E major’s family includes chords like A major (the subdominant, or IV), B major (the dominant, or V), and others like F-sharp minor (ii) and G sharp minor (iii). The opening instrumental has E major, A major, and F-sharp minor, so we have no issues so far (although the ostensible home key, E major, is only used in first inversion, once again destabilizing this a bit and making it more ambiguous than it’d otherwise seem.)

Then the vocals begin (“I may not always love you”), and they begin on a D-major chord. Problem is, D major is not in the family of E major: it’s at best a second or third cousin. So at the very start we’re in the “wrong” key (though we barely if at all established a “right” key!), and the wrong key is itself in a very unstable second inversion. Then he moves to a B-minor chord, another unrelated harmony. This is one of the big reasons why the issue of “key” is so contentious: lots of songs will go to weird places once they’ve established a home base, but Wilson hasn’t even given us that. We’ve been untethered from convention.

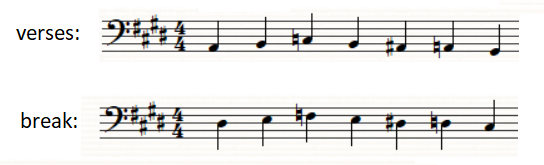

Yet “God Only Knows” doesn’t feel unstable: it feels tightly and satisfyingly structured in the moment, in part because of how miraculously Wilson seems to weave together these disparate elements according to a logic unconventional in pop music. My favorite bit of subtle structuring involves the break, which (of course!) begins by jumping to the thoroughly unrelated chord of G major (in second inversion, natch). From there, he uses the change in key to repeat the bass line/chord structure of the verses in a disguised way. Once we isolate the bass from the vocals (this is the “baaa baaa ba-ba baaa…” section) and instruments, it’s easy to see that it’s actually the same line, just raised a bit (a fourth) higher:

Whether we consciously recognize this echo (and again, Wilson hides it by changing all the stuff on top), it provides the song with a kind of implicit, almost subconscious structuring that makes an otherwise strange digression feel like it’s of a piece with what we’ve heard so far. (For those of you who like the gritty details, the harmonic progression is identical for this section, as well: V(4/2)–I(6/4)–♮ii(dim7)–I(6/4)–♯IV(m7♭5)–IV–I(6), only the reference key has changed.)

There’s just too much to dig into here, so if you have some technical background and want to feast on all the existing analysis out there, I can promise you it’ll make for a rewarding meal. For this brief post, I was especially reliant on Daniel Harrison’s (very technical) article “After Sundown: The Beach Boys’ Experimental Music” (available as pdf here), a blog post by composer Gary Ewer, another by Greg Panfile, an especially good discussion on Reddit, and various Youtube videos. I’d note that some of these notate the song incorrectly, but look: it’s a weird and muddy piece of music, so there’s room for error.

Finally, for a special treat, here’s Brian Wilson in the studio with the Wrecking Crew, directing the performance of its instrumentals. Enjoy!

Notes:

Some technical stuff on that root v. actual example: The * indicates a fully diminished chord, which, to put it as simply as possible, is “nothing but feet”: i.e., any inversion looks exactly the same, so it doesn’t “invert” the way other chords do (tho we sometimes write it as inversions if we need to stress its relationship in the harmonic “family,” to to speak).

The ** is a bit more contentious. Usually this is analyzed as something called a half-diminished chord (m7b5), but others have convincingly suggested that Wilson is taking a standard C#-minor chord and, due to the chromatic bass line, adding the A# as a passing tone, thus I notated this as a C# in the “root position” example and an A# in the “actual bass” version.